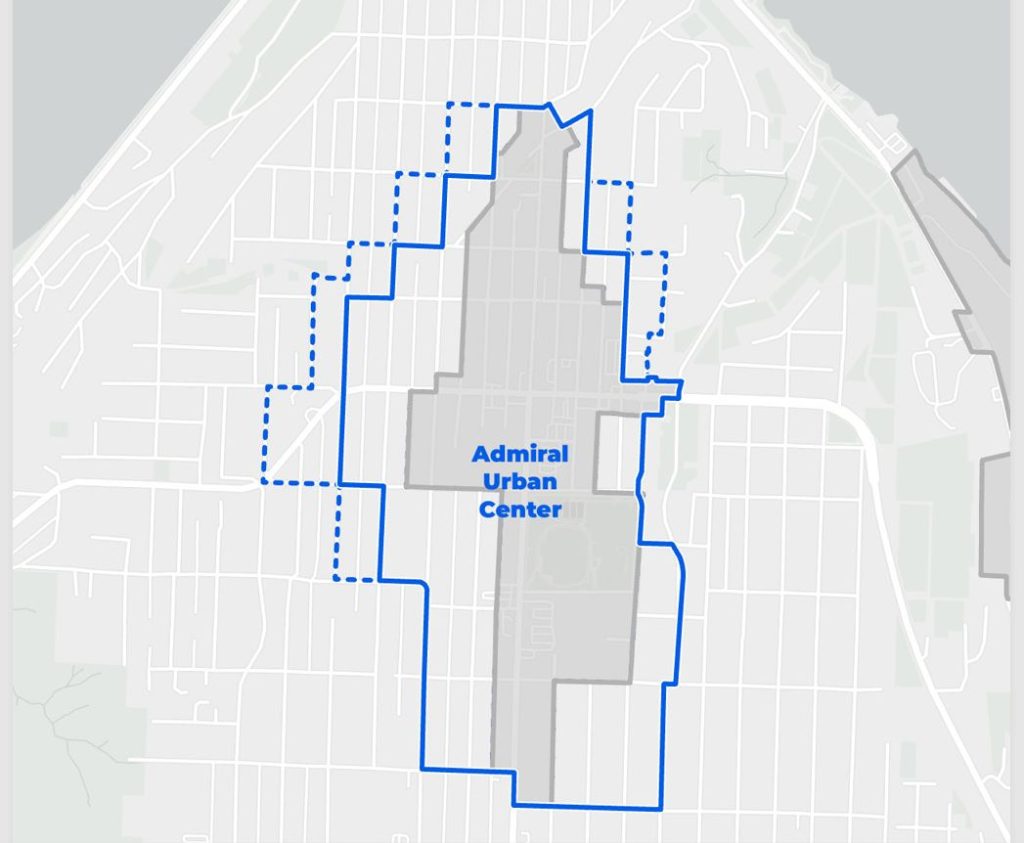

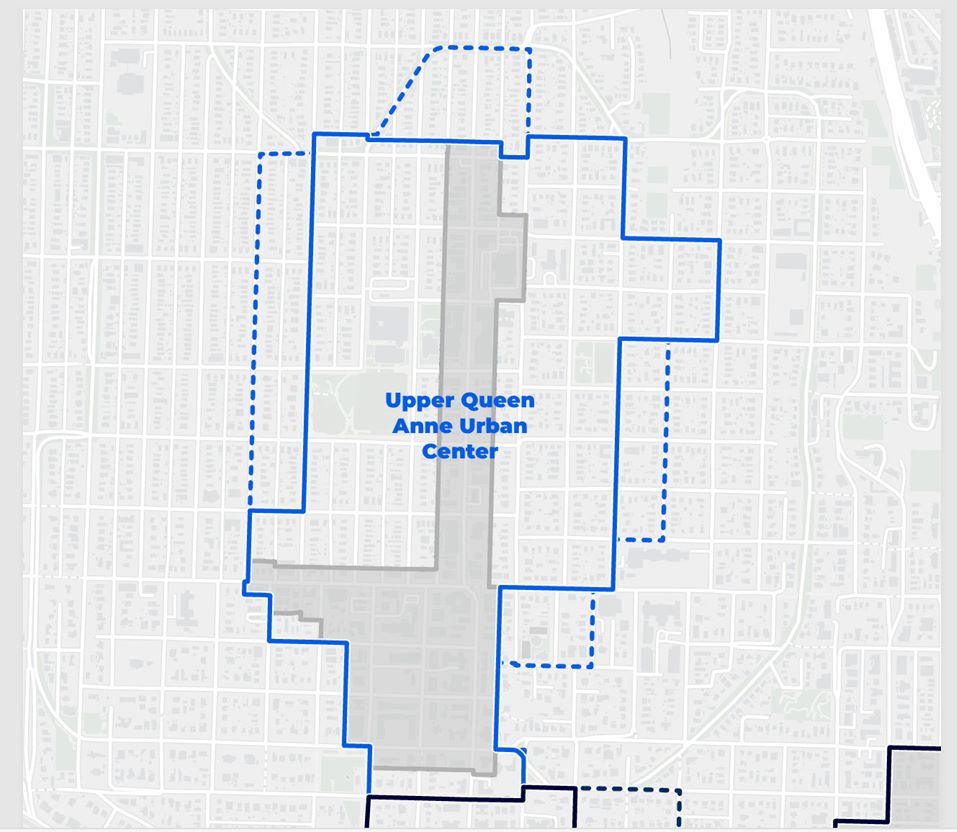

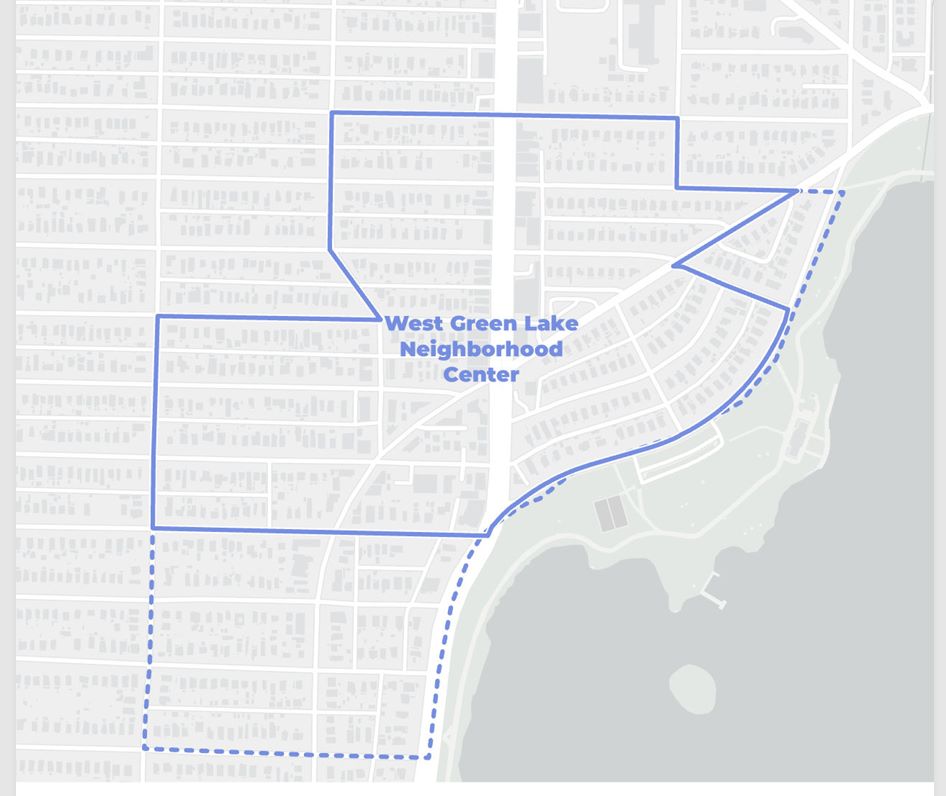

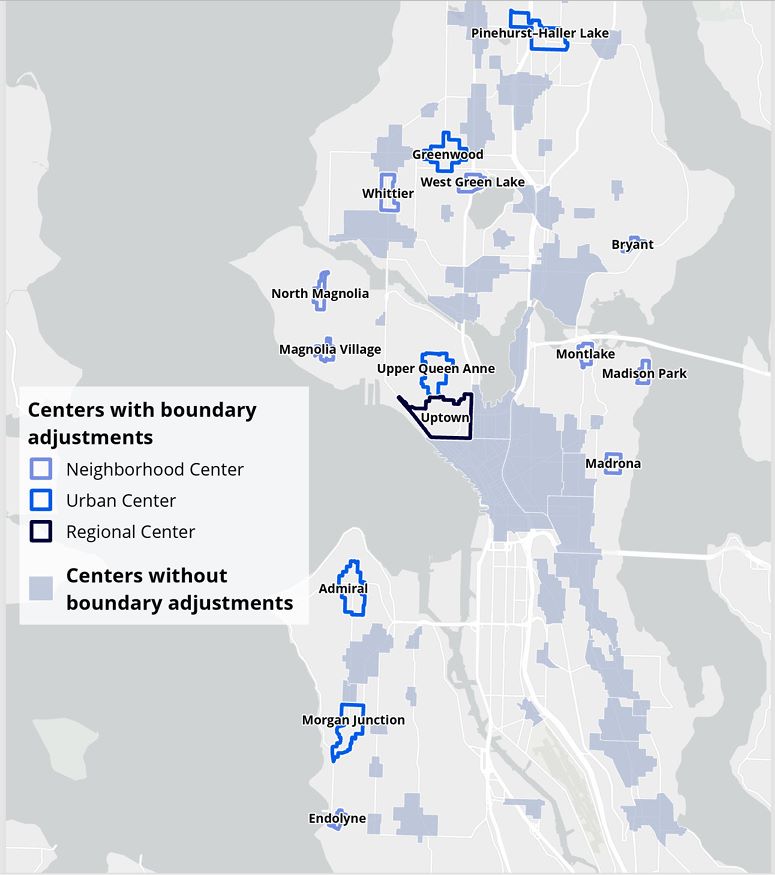

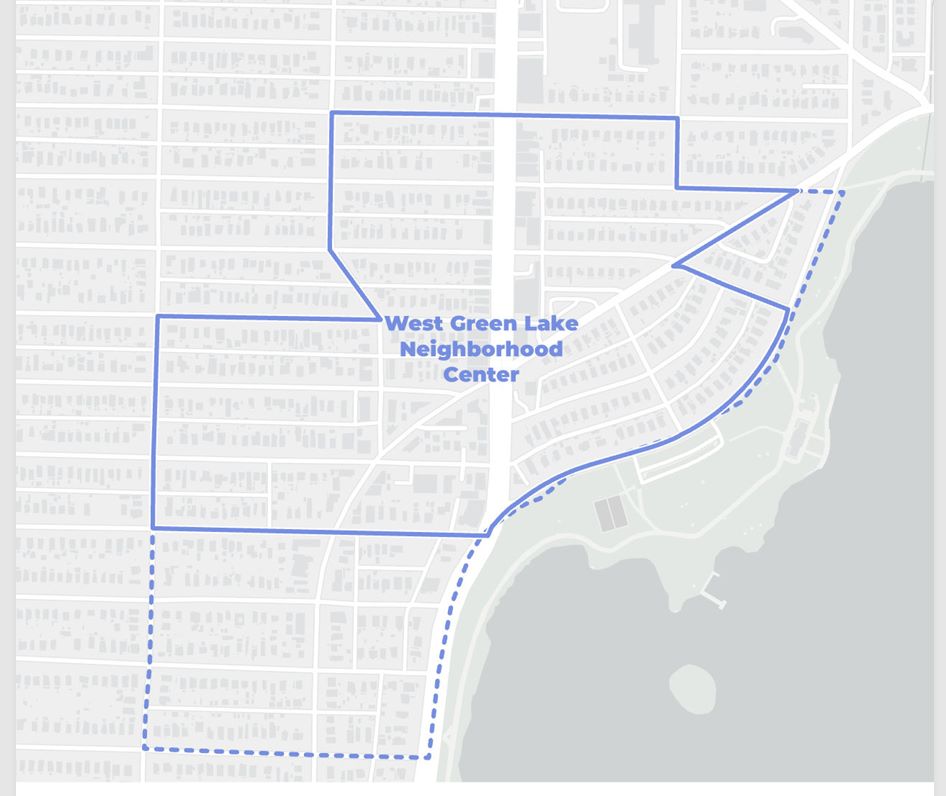

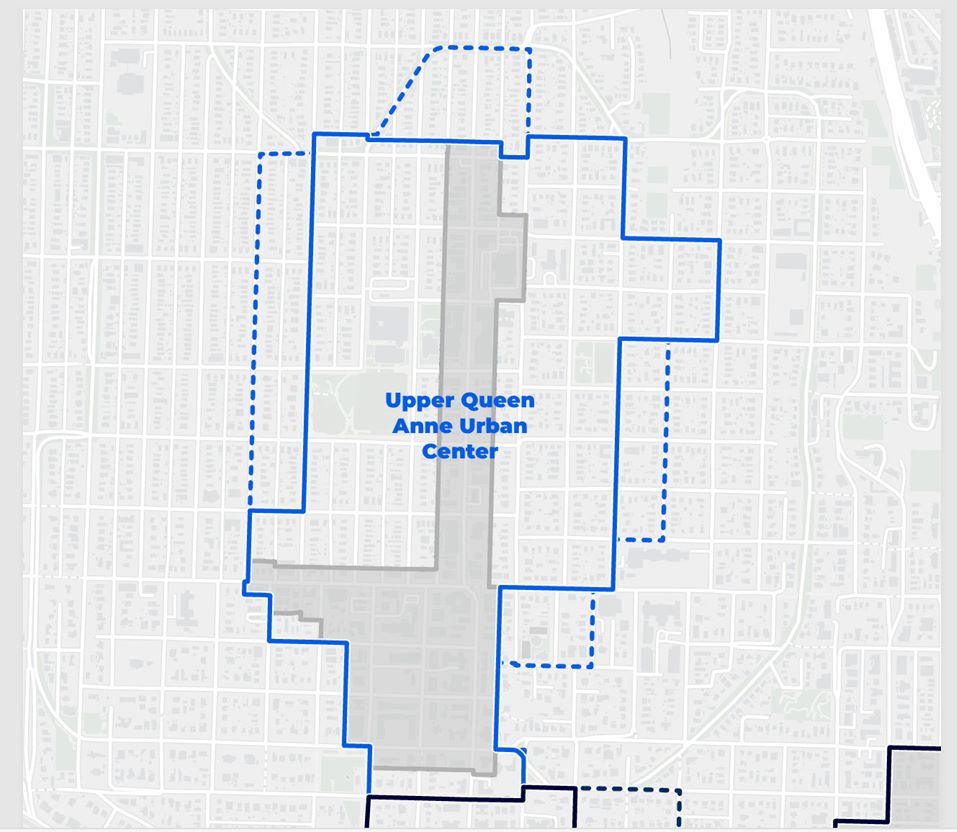

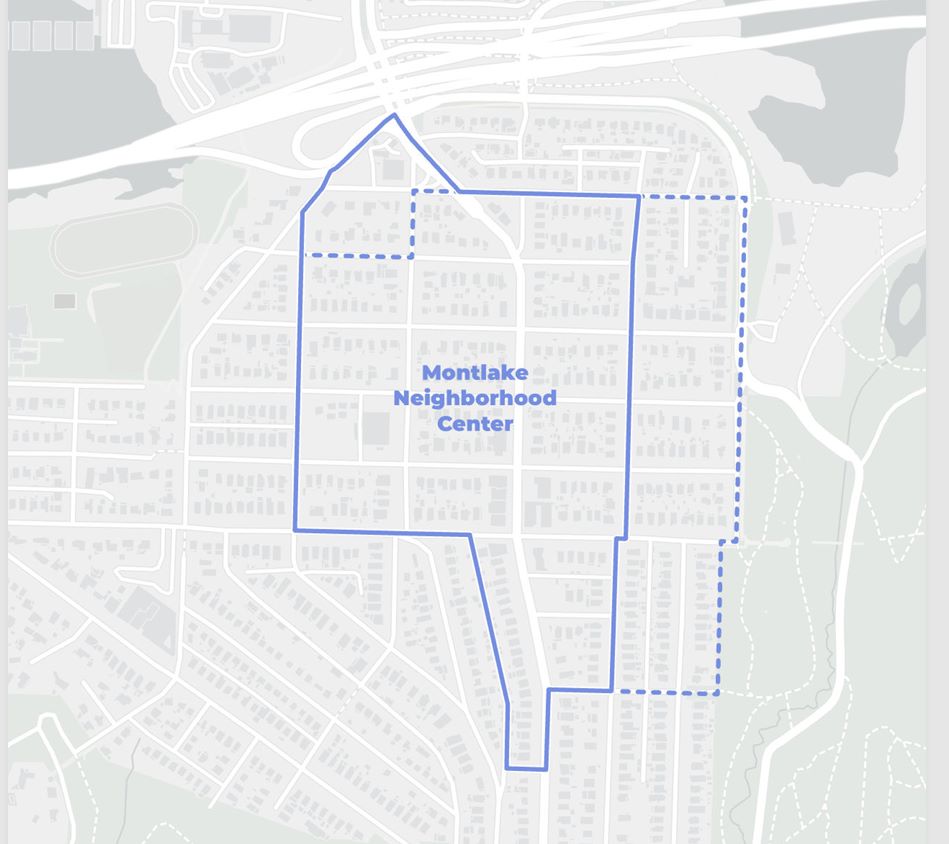

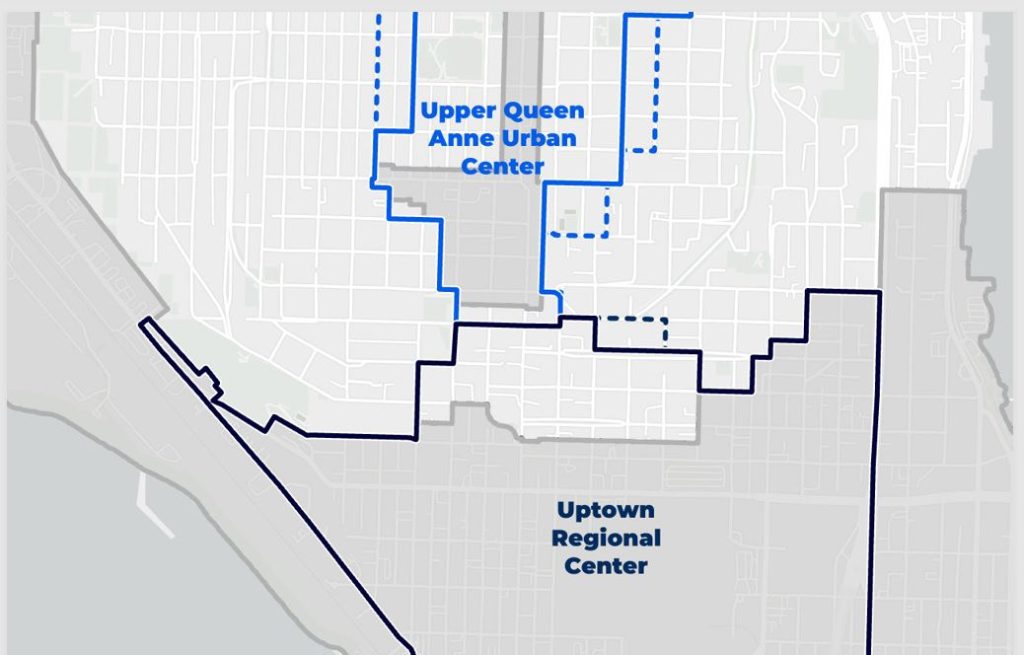

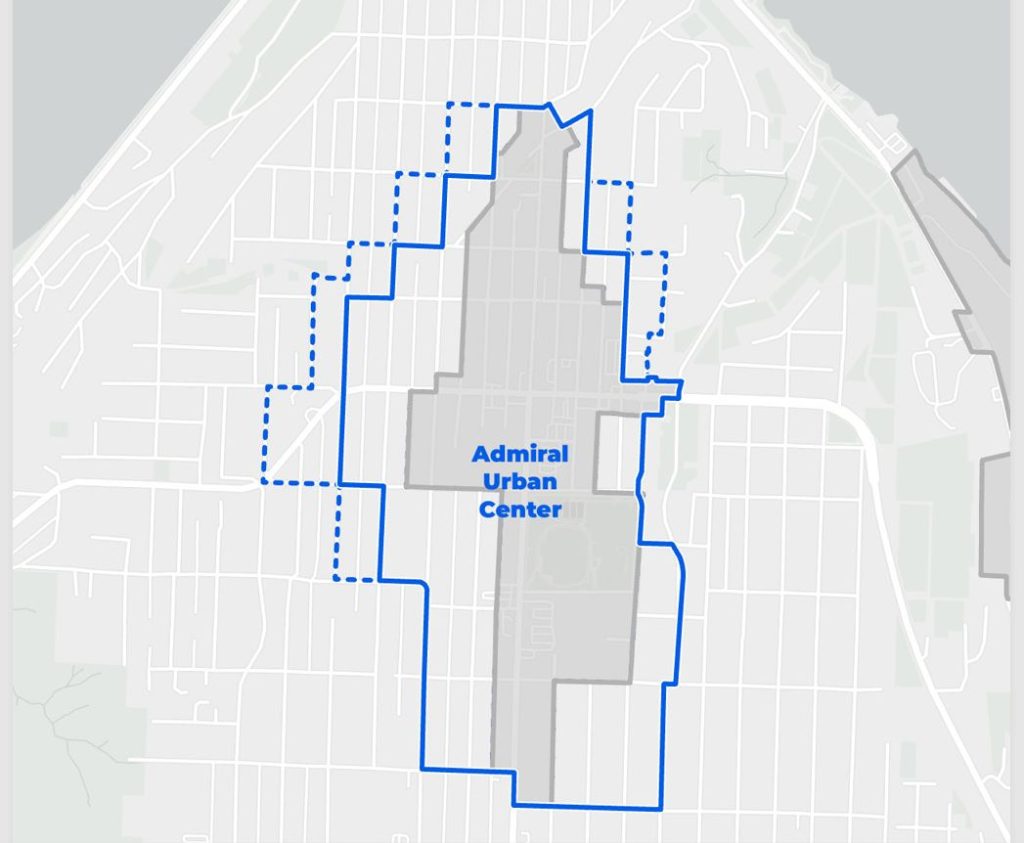

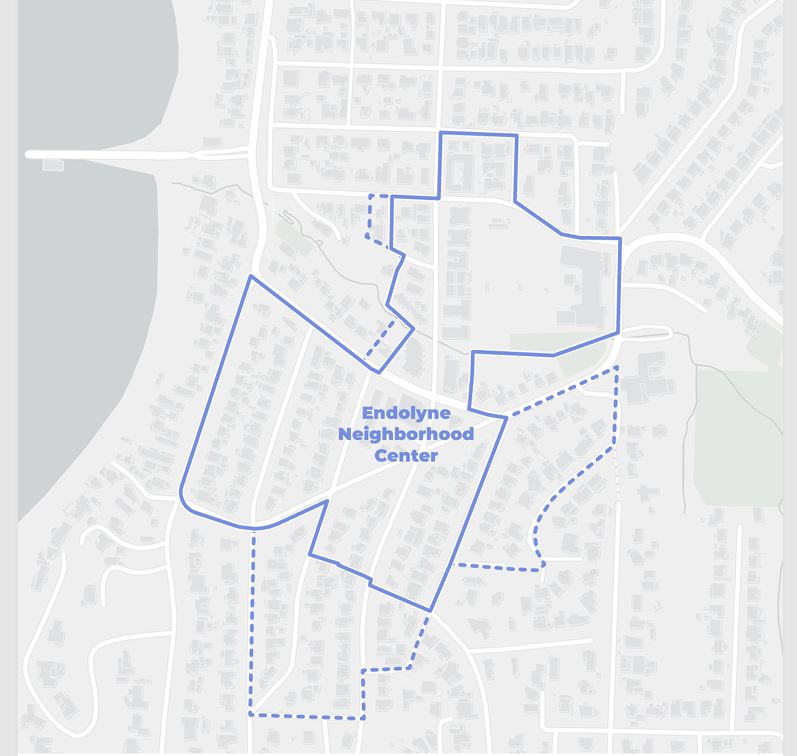

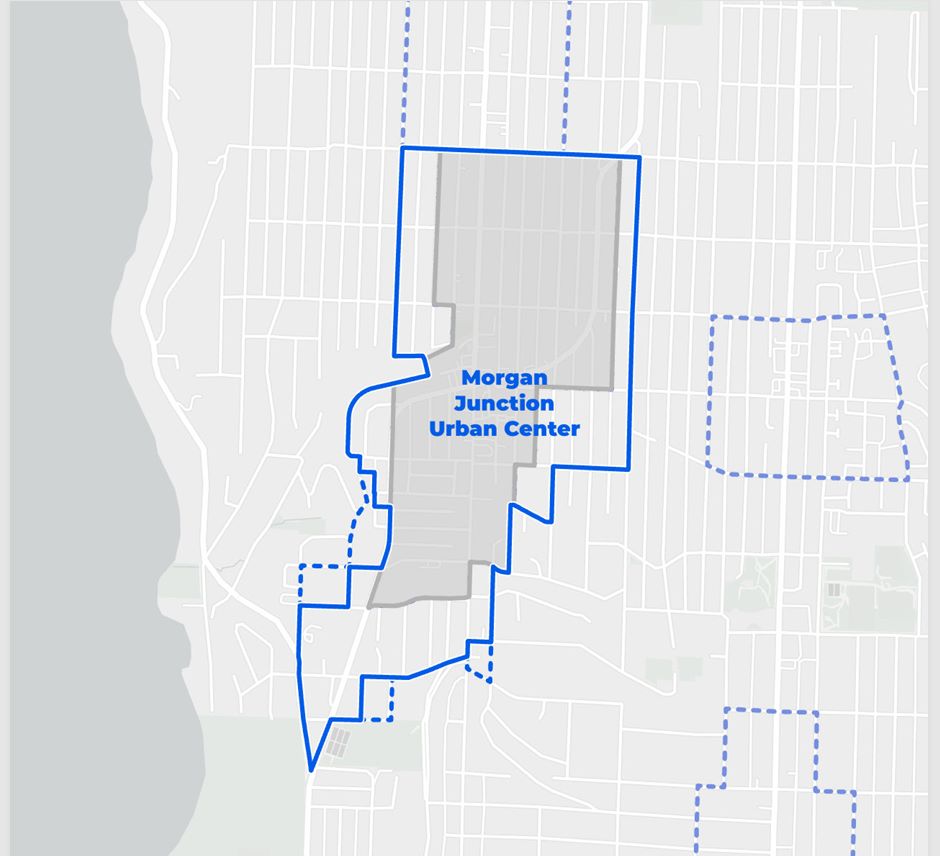

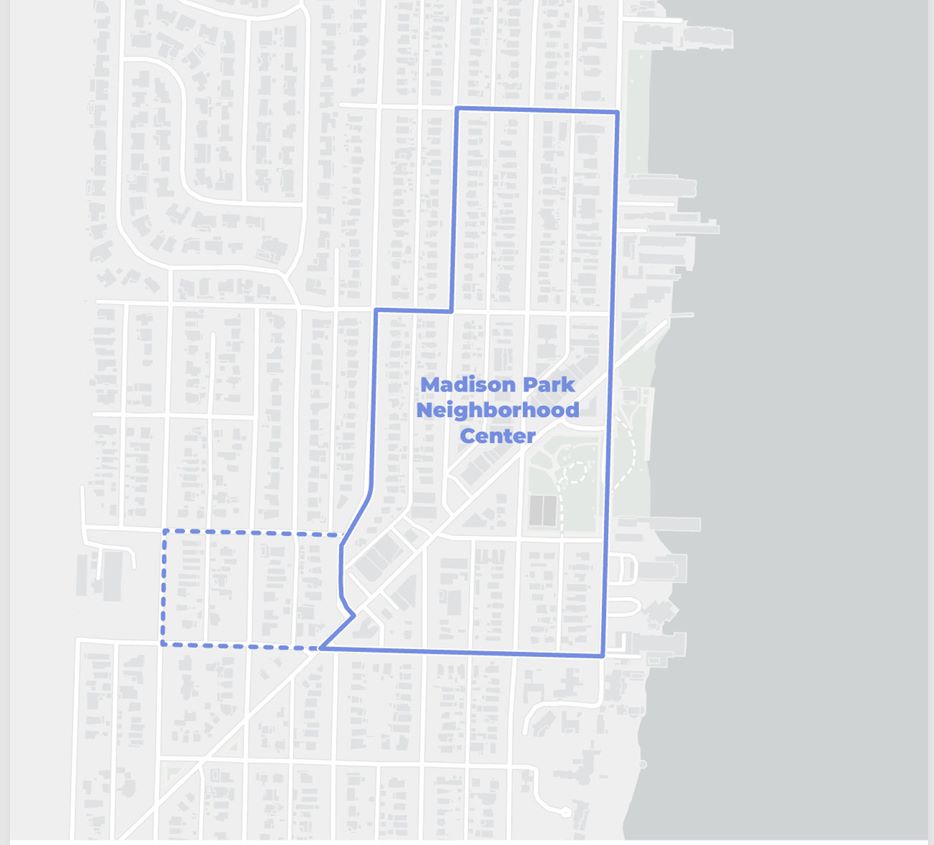

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell appears to have cold feet about the dimensions of nine neighborhood centers and six urban center expansions he proposed last year. Revised maps that have recently been quietly circulating among neighborhood groups and housing advocates indicate that 14 centers have been shrunk, their boundaries whittled down in size. In some neighborhoods — such as Upper Queen Anne, Admiral, Endolyne, and West Green Lake — the cuts are significant, shaving dozens of blocks out of the centers plan.

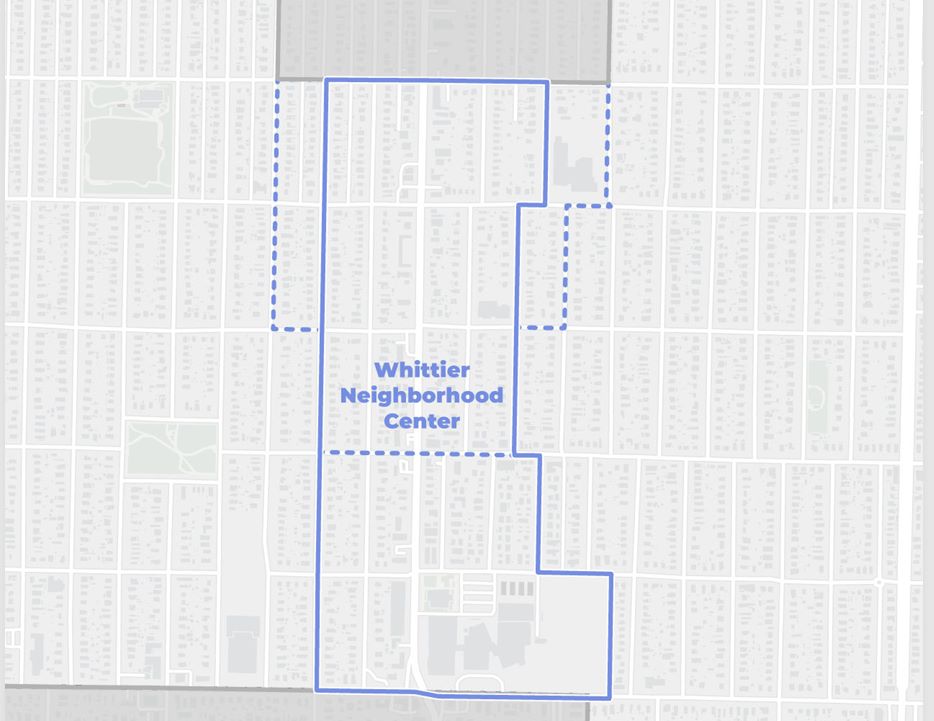

A 15th revised center, Whittier (just north of Ballard) could end up being a wash or even a net housing gain, with the revised borders shrinking in width, but extending farther south.

The scaling back comes on the heels of vocal opposition to allowing apartment buildings on additional blocks in those neighborhoods, with at least a dozen online petitions pushing to scale back or entirely remove neighborhood centers from the city’s growth plans.

Areas removed from centers would still face state-mandated middle housing changes than makes fourplex zoning the minimum level citywide, with sixplex zoning invoked near major transit stops. However, greater housing densities had been envisioned previously, including some sections of Lowrise 3, where five-stories apartments would have been allowed.

Mayoral spokesperson Callie Craighead confirmed the map’s authenticity and that the revisions now represent the Mayor’s active proposal.

“OPCD and the Mayor’s Office will be presenting these maps to the Select Committee in June,” Craighead told The Urbanist. “The initial draft of Future Land Use Map did not reflect feedback from the fall 2024 community engagement process. Following that engagement and conversations with Councilmembers about unique local conditions like slopes and other constraints, OPCD proposed the adjusted boundaries for some of the Neighborhood Centers. No Neighborhood Centers were removed.”

The loss of area is important because the plan’s centers are where virtually all of the apartments are projected to be built. Given the high cost of single family housing, apartments provide nearly all of the working class housing opportunities in Seattle, whether nonprofit-built or market-rate. In other words, centers are the main drivers of affordable homebuilding, and shrinking them will likely lead to less affordable housing.

The Seattle Office of Planning Community (OPCD) proposed adding as many as 50 neighborhood centers in an earlier internal draft, but reporting by The Urbanist revealed they were overruled by the Mayor Bruce Harrell’s policy team, who slashed that number in half in the draft plan that was released to the public. Last fall, Harrell added five more neighborhood centers, pushing the total to nearly 30 in his plan. This suggests Harrell was looking to (moderately) expand apartment zoning in his plan. But the contractions mapped this spring indicate a reversal in momentum.

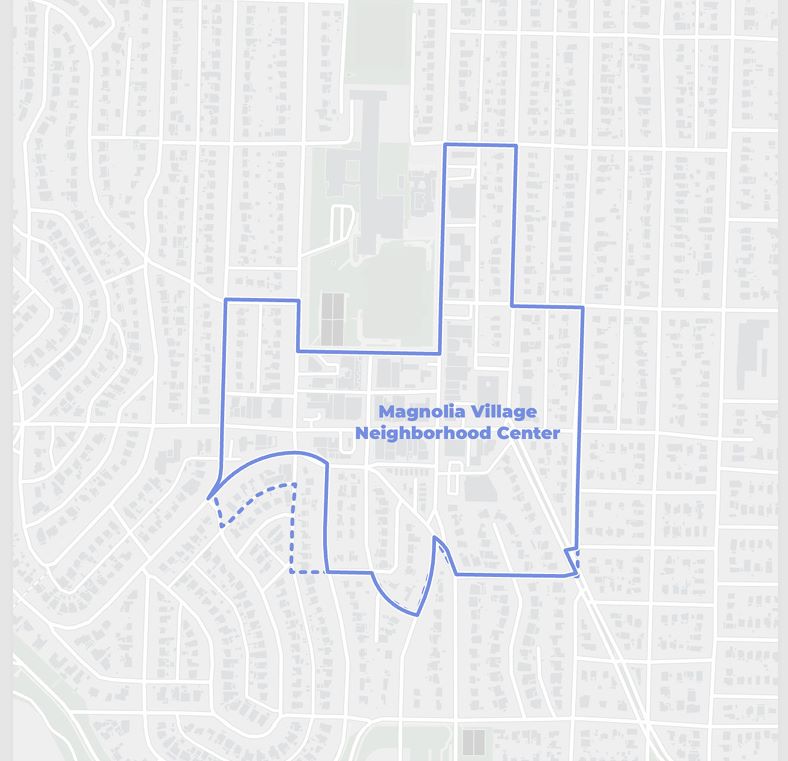

The idea behind neighborhood centers is to create small pockets of multifamily housing density, typically centered around a existing small business districts. OPCD has said its rule of thumb is to extend the new center a radius of 800 feet from this commercial core. Within these areas zoning tops out at mixed-use midrise building up to six stories in height and generally tapers off at the edges.

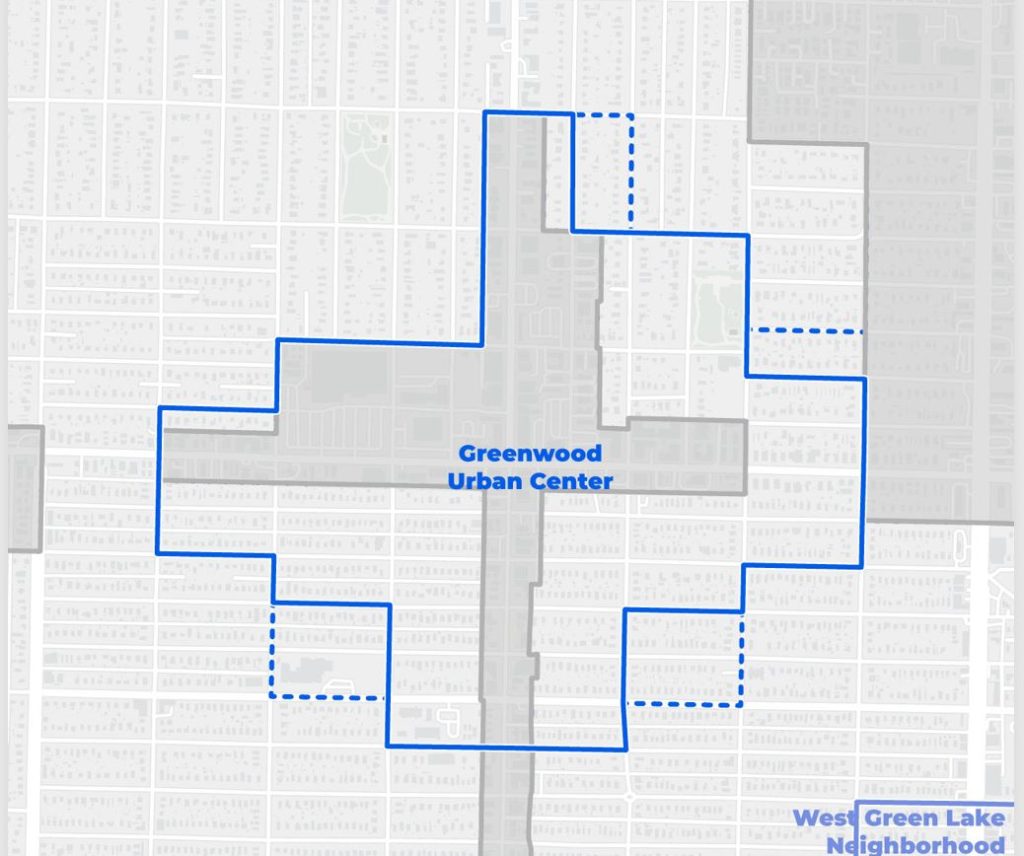

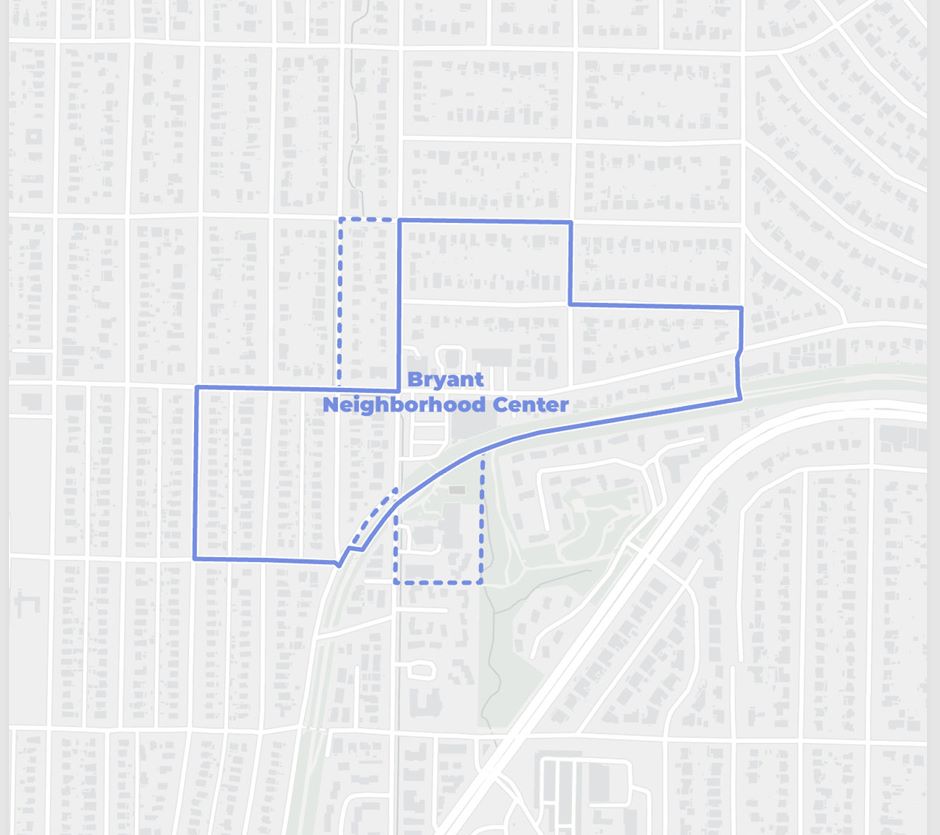

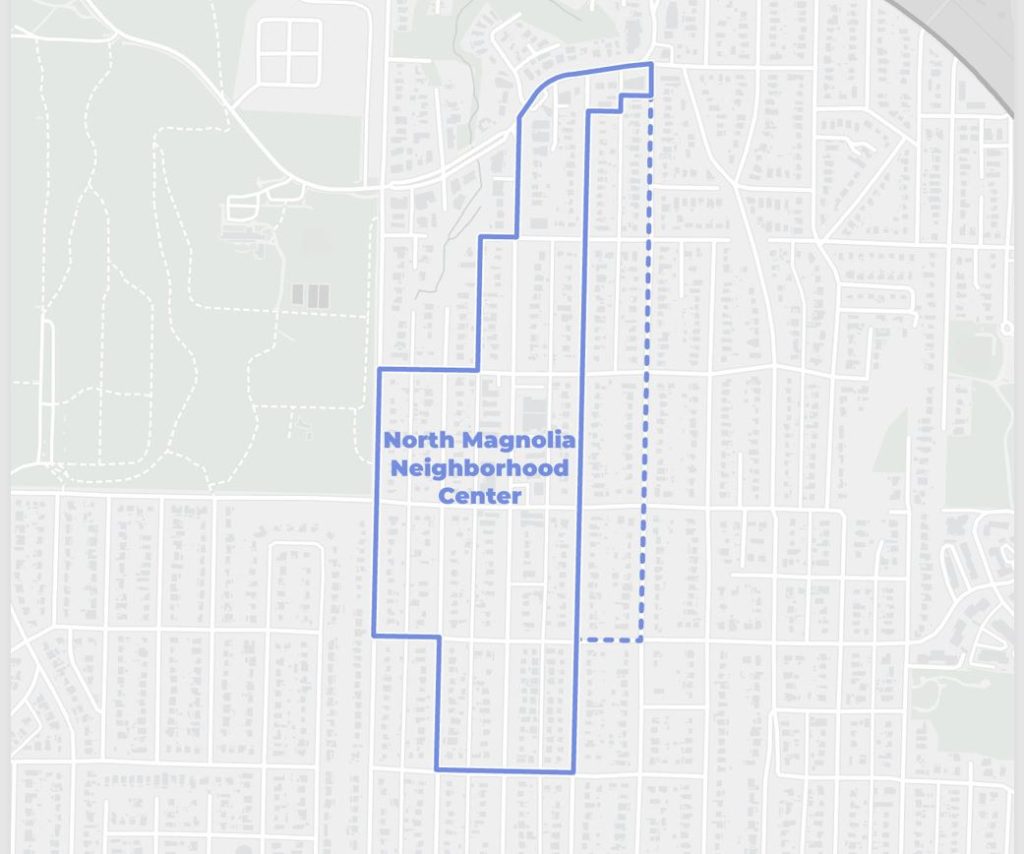

Nonetheless, proposed centers vary widely in size and shape. The Bryant and Endolyne neighborhood centers essentially spans just eight large blocks each, while North Magnolia is about 11, after four blocks were shaved off the plan. Urban centers are supposed to be larger in scale, but some are only moderately bigger, including the newly shaved down Upper Queen Anne and Greenwood.

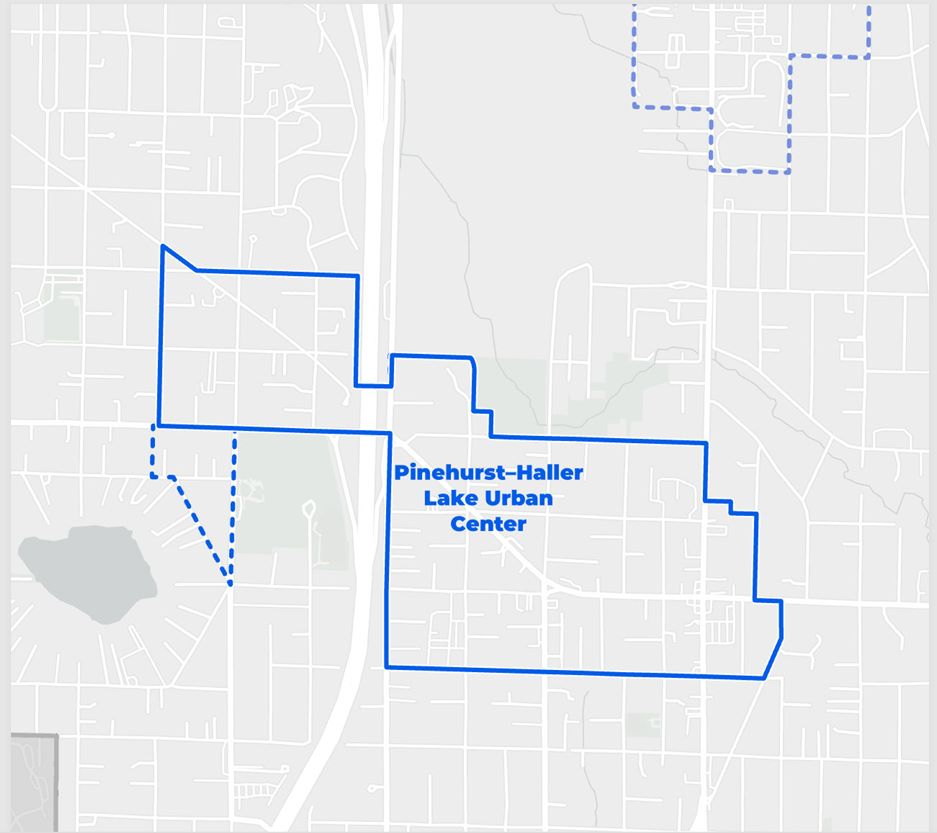

The urban centers date back to Seattle’s 1994 Comprehensive Plan, which laid out the “Urban Village Strategy.” The Pinehurst/Haller Lake Urban Center is the only new urban center added to the mix since then, though borders have been revised on occasion.

Advocates push for housing expansion, not retraction

Housing advocates have been pushing the city to expand growth centers, not shrink them. The Complete Communities Coalition — a broad alliance of advocacy groups including unions, nonprofits, business, and builders — listed adding additional neighborhood centers second in their list of priorities to improve the growth plan, while expanding the proposed centers was the group’s third priority. (Note: The Urbanist is a member of the coalition, though newsroom staff do not participate in coalition work.)

“Expand the boundaries of proposed neighborhood centers to ensure their scale can support essential amenities like grocery stores,” the group wrote on its website. “We suggest expanding these boundaries to encompass the area within a five-minute walk around a central point.”

Additionally, Seattle Planning Commission has also pushed for more and larger neighborhood centers.

Some neighborhood organizers are not thrilled with the shifting borders either. With light rail set to arrive at N 130th Street (next to Pinehurst and Haller Lake) in 2026, residents have been hoping to get clarity on rezone plans so they can begin planning redevelopments and understanding what the future might hold for their immediate block.

Renee Staton, a Pinehurst organizer who has long fought to get the 130th Station and zoning changes to support it, expressed disappointment that the plan continues to shift.

“The original proposal showed a commitment to doing the right thing toward bringing much-needed new housing across Seattle. I’m disappointed to see this being rolled back, but am glad to see that increased density is still being proposed,” Staton told The Urbanist.

Unfortunately, nearly a decade after the station was approved by regional voters in the Sound Transit 3 ballot measure, Pinehurst/Haller Lake still hasn’t seen a rezone, and the scope of the plan just shrunk, apparently. The continued rezoning delay has also elicited criticism from Sound Transit Board members like David Baker — who has since left the board after losing his Kenmore City Council seat — arguing the region has invested too much in stations for the surrounding land to be squandered and left to low-density uses.

“In terms of the Pinehurst Station rezone, we’ve been discussing this since the community first started advocating for the station in early 2015,” Staton said. “We expected the zoning would be finalized this summer and many are eager to see the process move forward so they can have clarity on their own personal next steps.”

For the mayor’s part, his team argued the map changes were minor, and based on feedback from councilmembers. Overall, they contend the plan roughly doubles Seattle’s zoned housing capacity, even with the contractions. Councilmembers Cathy Moore and Maritza Rivera, in particular, have appeared reticent about the scale of zoning changes and the encroachment into single family areas. Dan Strauss, on the other hand, has appeared eager to make adjustments to neighborhood center boundaries — but only if those changes maintain the total amount of housing capacity of the original proposal — a move that might explain why the only adjustment that expanded scope (Whittier) is within Strauss’s District 6.

“We believe these changes are minor, and incorporate the feedback OPCD received as part of the second round of community engagement and from conversations and community walks with Councilmembers,” Craighead said. “As part of their consideration of the legislation, Council can choose to adjust and refine the boundaries as well.”

All 15 revised maps

Zoning changes for all the neighborhood centers and narrow corridors along transit have been pushed back to 2026 following delays related to infighting within the Harrell Administration and homeowner group legal appeals. However, the City intends to define the boundaries of the centers in the One Seattle Comprehensive Plan later this year, before coming back to approve the zoning within them next year.

The revisions from Harrell could indicate the momentum is toward scaling back housing capacity as Council takes up the plan. However, councilmembers could end up going in the other direction as well — adding that capacity right back in. Recent polling and the feedback gathered on the growth plan indicate the broader public is on board with broad zoning changes, despite more localized pushback from some homeowners.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.