Building four homes is now legal on every residential lot in the City of Seattle, following a unanimous city council vote Tuesday. The land use code update puts Seattle in compliance with new housing requirements approved by the Washington State Legislature in 2023 — just ahead of the deadline looming on June 30. The change, which also allows sixplexes near light rail and RapidRide bus stations, is one of the biggest changes to zoning in Seattle in decades.

The interim ordinance will expire in a year, if it is not renewed. Council’s real work now turns toward adoption of a permanent residential zoning code. As part of that work, issues like the impact of lot coverage and setbacks on tree preservation, affordability mandates, and parking requirements are likely to be put front-and-center.

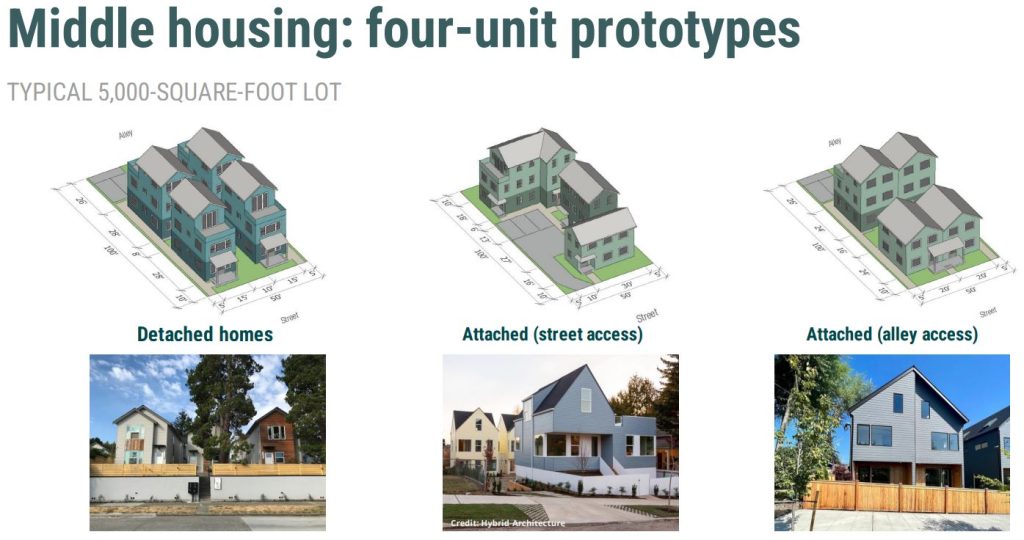

The code adopted Tuesday is a bare-bones framework to comply with House Bill 1110, a sweeping state law that is intended to make it easier to build more times of small, multi-unit development (known as “middle housing”) like townhouses, duplexes, triplexes, stacked flats, and cottage housing. Without an interim ordinance, the City would have adopted a state-imposed model code automatically, but the new code is missing many of the elements of Seattle’s strategies to explicitly encourage the construction of more housing.

Mayor Bruce Harrell has proposed additional housing reforms that include adding 30 new “neighborhood centers” spread across the city where more intensive growth including multifamily housing ranging up to six stories in height would be allowed. The mayor also floated additional density within one block of major transit corridors. However, those changes were split into a Phase 2, as the overall growth plan — initially imagined as a singular “One Seattle Comprehensive Plan” — lagged and state deadlines for middle housing changes loomed.

Ultimately, phasing the plan wasn’t enough to ensure permanent legislation could pass in time, as legal appeals from homeowner groups (even quickly dismissed ones) ate into the little cushion the Harrell Administration managed to work into their timeline. Hence, the City opted to use an interim ordinance enacting a simplified policy, which allows for a quicker process and fewer avenues to appeal.

Absent is the proposed incentive program to encourage stacking units on top of one another, available to property owners redeveloping lots at least 6,000 square feet in size. Also not included is an additional incentive for including affordable housing within middle housing developments. Both were proposed by the Harrell Administration as part of a proposal for permanent zoning last year, but were left out of the interim code — in large part because they had been tied up in a set of appeals against the overall One Seattle growth plan, now since fully dismissed.

On the flip side, none of the so-called “poison pill” amendments Seattle’s Planning Commission has cautioned against adopting in recent weeks were put forward. The controversial amendments signaled by councilmembers or staff reports included additional barriers to the removal of large trees on existing lots and requirements for builders to set aside a certain number of units as affordable in order to build any middle housing. Instead, the amendments adopted were all fairly narrow in scope, adopted without much contention.

The issues could come back around. The council adopted a work program laying out what issues will get tackled over the coming months: a full laundry list of potential barriers that could impact how much housing Seattle is able to add in its low-density neighborhoods. Among the issues: “reviewing density limits and development standards for properties with steep slope critical areas,” “[c]onsidering the modification of off-street parking requirements to support City goals,” and “[c]onsidering adjustments to setbacks and amenity area regulations to maximize tree protection.”

The issue of tree protection is likely to dominate deliberations over the coming weeks, as maintaining the city’s tree canopy becomes a key talking point in pushing back on additional flexibility for builders. At a final public hearing on the proposal early last week, commenters wearing plastic tree headbands showed up in force to support policies intended to preserve existing large trees across the city. Many spoke in favor of an amendment put forward by District 5 Councilmember Cathy Moore keeping existing large setback requirements in the city’s neighborhood residential (NR) zones in place.

The advocacy group Tree Action Seattle had galvanized support for the amendment via its email list over the days prior, even though the actual text of the amendment didn’t drop until until a few minutes before the hearing was scheduled to start. “The current interim code reduces setbacks without adding space for trees,” the email stated. “We can’t afford to pave over our urban forest with no plan for climate resilience.”

While both urbanists and groups like Tree Action Seattle present the tradeoff between tree protections and homebuilding as a false dichotomy, there’s considerably less agreement on how to actually move forward. While the tree advocates argue that strict rules need to be in place to prevent tree removal and to force developers to build as densely as possible, housing advocacy groups have instead argued that those rules stifle the very thing that is able to protect the environment: robust urban density (instead of suburban sprawl).

“Cities are crucial to protecting our environment by reducing carbon emissions through slashing vehicle miles traveled, providing robust public transit to do so, reducing the tire particles poisoning our fish, orcas and other wildlife, and other environmental impacts of cars and sprawl,” Jazmine Smith and Robert Cruickshank wrote in a joint op-ed in The Urbanist on the topic last month. “When we aren’t doing our part as a city to plan for smart, livable cities, and communities, trees and orcas suffer.

Moore’s amendment would have required that new development maintain a 20-foot front yard — or an average of the yards in front of the “single-family structures” on either side, if less — and a rear setback of 25 feet, or at least 20% of an entire lot. But it was withdrawn before it could reach a vote, with Moore citing potential legal issues with how it was constructed. Housing advocates had already started pushing back on the amendment, noting the detrimental impact of keeping such requirements in place.

“Seattle’s current setbacks in Neighborhood Residential (NR) zones were designed for single-family homes. Preserving these outdated standards under HB 1110 implementation would severely limit—if not eliminate—the city’s ability to deliver the four to six homes per lot that state law now mandates,” Parker Dawson, Seattle Government Affairs Manager for the Master Builders Association of King & Snohomish Counties, wrote in a letter responding to the amendment. “In most cases, these setbacks would make it impossible to achieve the proposed 50% lot coverage, thereby reducing or eliminating feasible paths to create needed and diverse housing supply including duplexes, triplexes, and other middle housing types.”

In place of her initial amendment, Moore instead proposed that Seattle follow the state model code, imposing 15 foot setbacks on development with one or two units, and reducing that to 10 feet with more units. Without any amendment, those 10 foot setbacks would have been the new standard. Moore’s revamped amendment saw eight of nine councilmembers in support, with only D6 Councilmember Dan Strauss opposing.

“Setbacks do not equate to trees, and that’s something that’s hard for me, because a setback can be paved. A setback can be used for a whole number of situations,” Strauss said ahead of his abstention on the amendment. He noted that the city’s existing tree preservation ordinance allows setbacks to be reduced by up to 50% in order to preserve a large tree, so keeping large setback requirements in place actually provides less flexibility to property owners to be able to preserve trees.

Despite broad agreement that encouraging development to be more compact is a way to ensure that existing trees are able to be preserved, onerous requirements are likely not the path toward encouraging that development, with numerous barriers in place that discourage the production of stacked flats in Seattle over townhouse development.

Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck, supporting the amendment, made a clear nod toward the fact that the full debate over the issue will likely continue over the next few months.

“While there is certainly plenty I can say about the subject of setbacks, I will be saving those remarks for when we come to this issue again in the permanent legislation,” Rinck said. “As far as I can tell, this in effect will incentivize greater density by giving better setback flexibility to three-plus-unit developments. We need more middle housing in neighborhood residential zones, and by granting greater flexibility to multi-unit developments from single family developments, we can build even more.”

While Seattle has now taken a major step toward legalizing the types of housing that have long been banned throughout much of the city, the biggest debates are still to come, with many policy parameters still very much up-in-the-air.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.