Under the current planning framework, Aurora’s future is bleak.

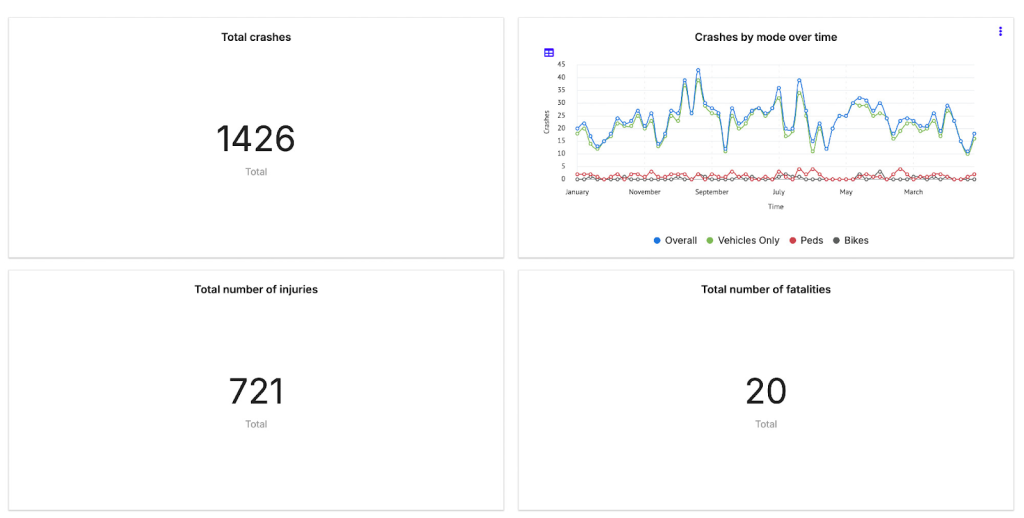

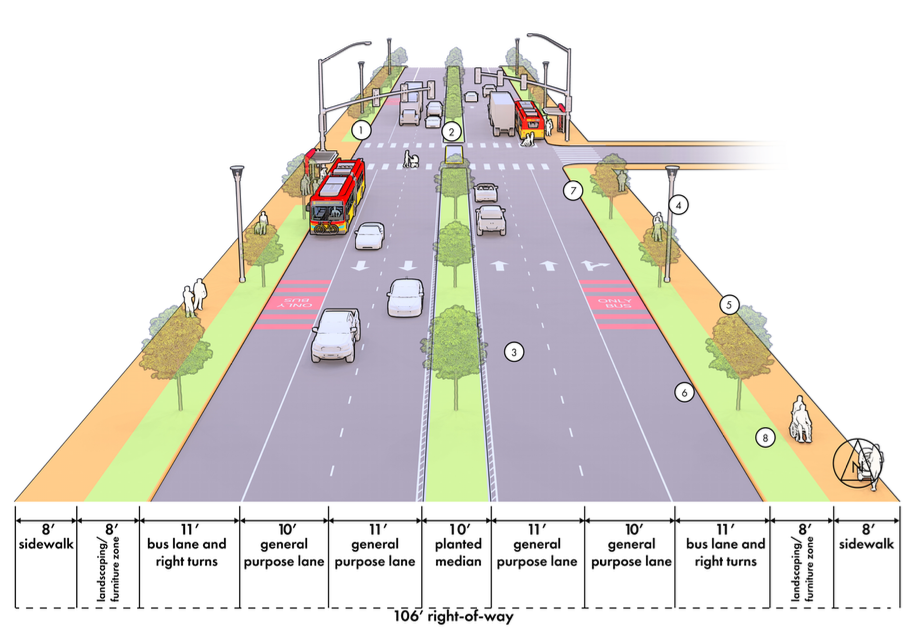

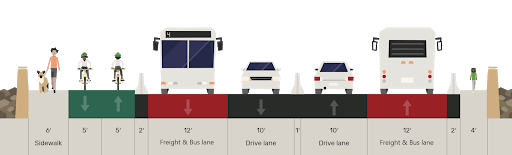

The Seattle Department of Transportation’s (SDOT’s) recently released Phase 1 Report on the Aurora Avenue Project is an abdication of the City’s own stated goals of climate resilience, racial equity, and eliminating traffic deaths through Vision Zero. Despite overwhelming evidence in their own modeling that general purpose vehicle lane reduction with prioritized public transit, pedestrian, and bicycle infrastructure perform significantly better across nearly every metric (most notably safety, equity, and livability), SDOT staff are envisioning the future of Aurora Avenue N to look nearly exactly the same as it has for the last 100 years: a dangerous, high speed, six- to seven-lane highway.

A faulty evaluation framework

SDOT weighs 18 measures in its $3 million Aurora study, aiming to improve pedestrian safety. The evaluation is categorized by implementation, safety and multimodal experience, property access and freight mobility, equity, city department alignment, and trees. We raise serious concerns as the factors are not given weight. There is no prioritization of safety, equity, or livability over any other evaluation criteria despite repeated, formal policy commitments from the City of Seattle including but not limited to:

- Vision Zero

- One Seattle Climate Action Plan

- Transportation Equity Program

- Seattle Transportation Plan

- One Seattle Comprehensive Plan

By treating items like “freight access” as equally important as “safe pedestrian crossings” or “air quality improvements,” the framework establishes a priority of car dominance. It discards the policy urgency of Vision Zero, the One Seattle Climate Action Plan, Seattle’s Race and Social Justice Initiative, and the One Seattle Comprehensive Plan.

The net effect is that even high-performing pedestrian/transit concepts are buried under the notion of “balancing” evaluations that are a continuation of the status quo.

Aurora’s actual traffic patterns are grossly misunderstood

The most glaring blind spot in the report is its misunderstanding of Aurora as a regional commuter route, and its failure to acknowledge the corridor’s primary function as a local connector.

According to the study’s own sensitivity analysis, fewer than 10% of trips on Aurora are regional “pass-through” trips. Most trips within the eight-mile section of Aurora Avenue that SDOT is analyzing:

- Begin and end within the eight-mile corridor or nearby neighborhoods

- Are short-distance, local trips (e.g., to grocery stores, jobs, schools, social services)

- Could reasonably be shifted to walking, biking, or transit if the infrastructure existed.

Yet, the evaluation still centers vehicle level of service and recommends preserving capacity that does not meaningfully serve regional traffic.

Designing Aurora Avenue as a highway does not match how the community actually uses it. Treating it like a regional expressway continues to perpetuate its equivalency to Interstate 5.

Instead, the study should have clearly stated: Aurora is a mixed-use, urban arterial. It should serve local trips, prioritize access and connections to current and future neighborhood destinations, and enhance short-distance connectivity, not accommodate long-distance drivers, who can use I-5 and often do.

SDOT treats maintaining vehicle capacity as a legitimate option

This concept proposes minimal change to the current design and prioritizes general-purpose lanes. While the study acknowledges it performs poorly in all non-vehicle prioritizing categories, it is still evaluated alongside safer, more equitable, and environmentally preferred designs and ultimately undermines all other proposed concepts that could improve walkability, and transit service with center-running bus lanes.

Including this concept in the study as a real alternative rather than a perfunctory baseline communicates that preserving car capacity is reasonable on a corridor with repeated vehicular and pedestrian deaths, high transit ridership, and land-use slated for high density housing and commercial development. Modes that do not serve single occupancy vehicle priority are pitted against each other as “either/or” options. The premise undermines all proposed concepts such as the “walkable boulevard idea” presented in the report that is nearly indistinguishable from the road as it appears today.

In segments where pedestrian and cycling infrastructure is missing today, the continued push for a concept that does the bare minimum undermines Vision Zero safety goals and fails to reflect city directed and community priorities.

Fragmented racial equity and environmental justice analysis

The study includes two equity-related measures of “Pro-Equity Investment” and “Community Well-Being” and frames them as standalone criteria, rather than foundational to the entire evaluation.

The report emphasizes the equity process as being rigorous but the report avoids naming or identifying specific populations, impacts, or tradeoffs in its final summaries. It does not clearly explain how those communities would benefit or be harmed by each concept.

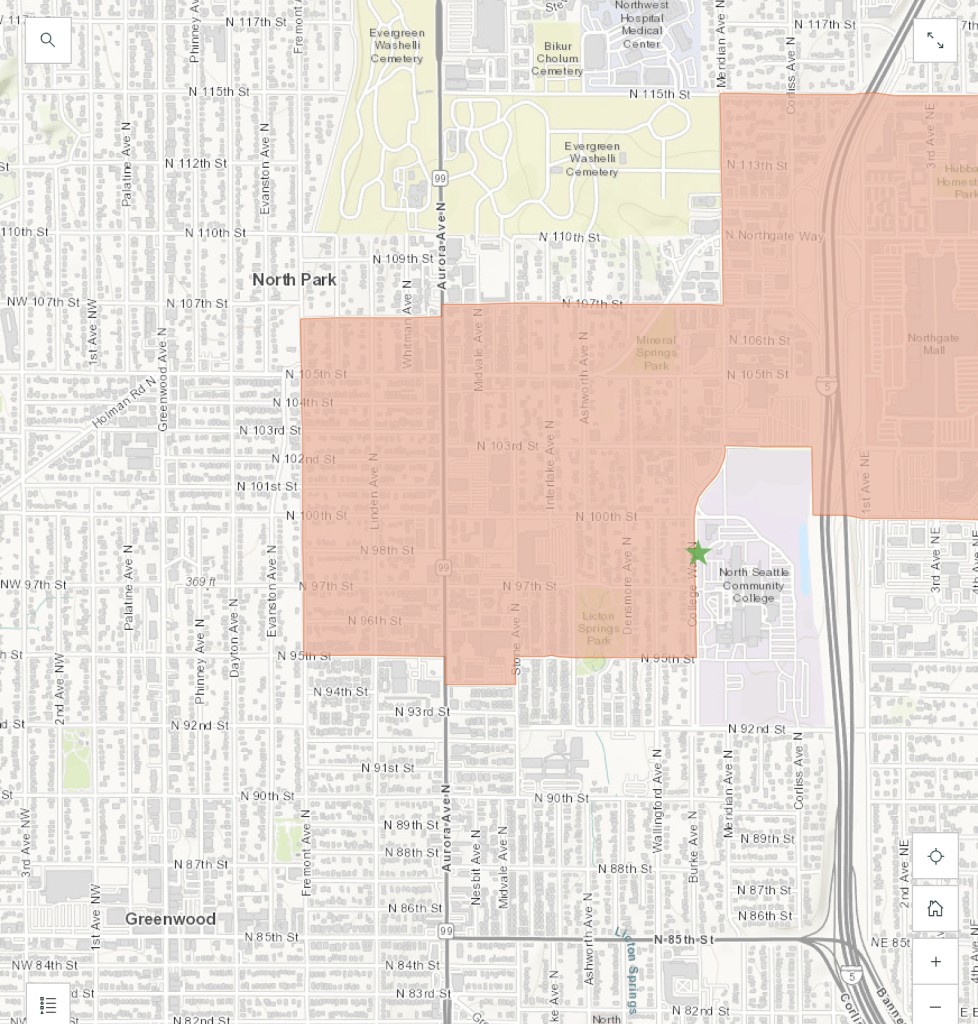

Aurora Avenue N traverses communities who are disproportionately endangered by unsafe road conditions, lack access to green spaces, have insufficient transit accessibility, and are overburdened by pollution.

The corridor serves essential social service hubs, low-income households, and many transit-dependent residents. Not grounding the evaluation in racial and economic justice is an egregious missed opportunity to lead with equity and repair harm.

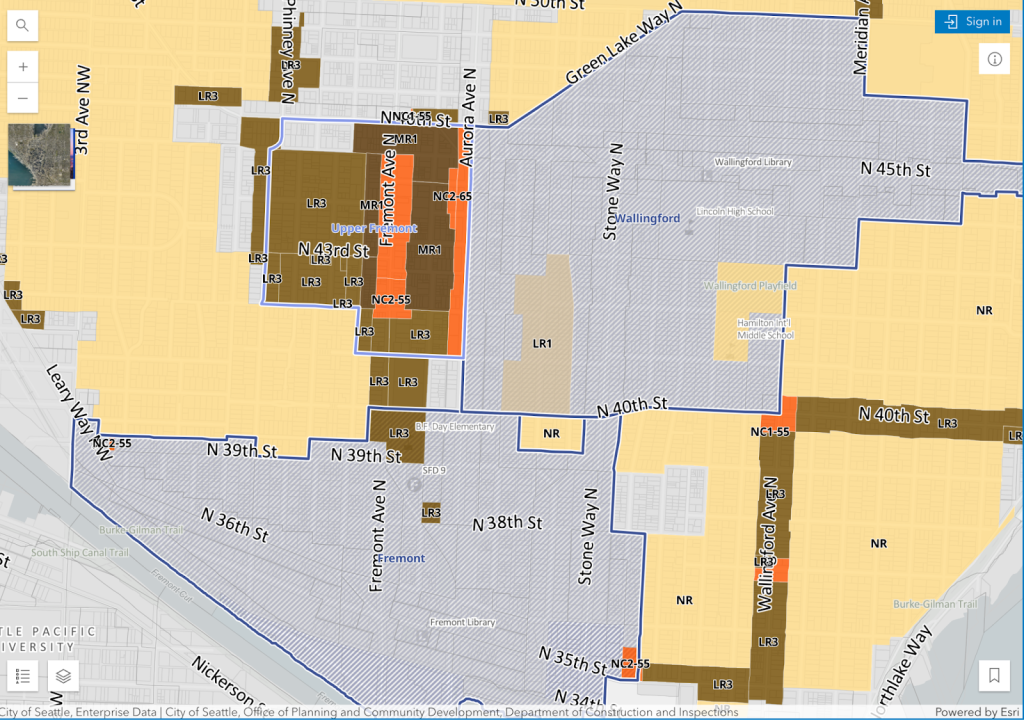

Land use, housing, and Regional Growth Centers are ignored

The corridor includes or borders multiple growth centers and urban villages, including:

- Fremont Urban Center

- Upper Fremont Neighborhood Center

- Wallingford Urban Center

- West Green Lake Neighborhood Center

- Aurora-Licton Springs Urban Center

- Greenwood Urban Center

- Bitter Lake Urban Center

None of the criteria considers these planned growth areas as outlined in the proposed One Seattle Comprehensive Plan. Key questions are left unanswered and unaccounted for:

- How do the design concepts support planned future growth?

- How will walkability, bikeability, and pedestrian access affect future development?

- How will public transit demand shift and adapt over time?

At $3 million, the report fails to answer the central question: What kind of corridor do we want Aurora Avenue N to be? A neighborhood-serving spine of mid-rise housing, safe crossings, and transit access? Or a dangerous and polluted car-centric cut-through with harmful health implications, similar to how it is today? The community response continues to show a desire for “better walkability and liveability.”

Without connecting the planning to the city’s One Seattle Comprehensive Plan, the report fails to demonstrate and undermines how the corridor design can align with Seattle’s housing and land use goals.

Health impacts from traffic are barely acknowledged

Despite frequent public complaints and stakeholder input about noise, air pollution, and stress caused by Aurora’s current conditions, the study makes no mention of quantifiable health impacts. There is no modeling of:

- Vehicle emissions

- Noise pollution

- Air pollution and particulate matter

- Proximity of housing and schools to dangerous volumes of traffic

Aurora Avenue N is a textbook example of environmental injustice: dense housing, elderly residents, unhoused individuals, underserved communities, and schools located along a high-speed, high-volume roadway with no buffer or mitigation.

Modeling for pollution or decibel (dB) readings for noise levels could have illustrated the health benefits of reduced traffic, added vegetation, or protected bikeways. Their absence shows a failure to consider lived experience and long-term wellbeing of people who live along the road.

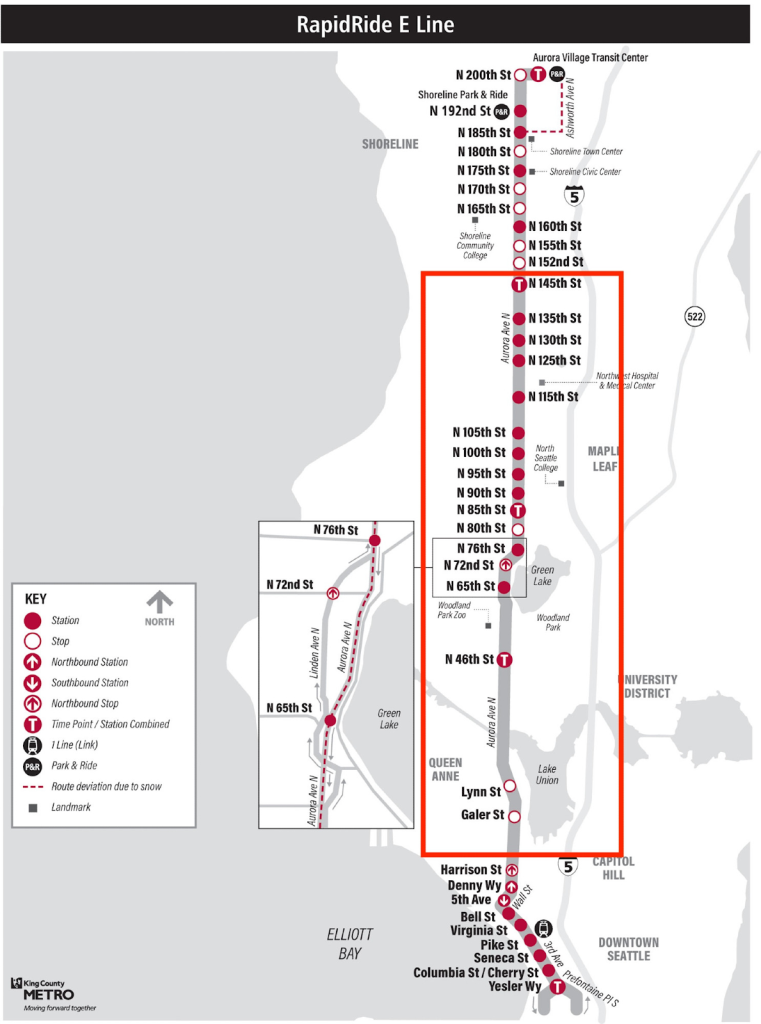

No transit expansion plan south of Green Lake

The study assumes the current E Line bus configuration with no mention that the segment from Roy Street to Green Lake is:

- Critically underserved by public transit (three stops spaced far apart)

- Lacks safe or ADA-compliant crossings

- Has little priority for future investments.

South of Green Lake along Aurora Avenue N is a transit desert in a growing, increasingly residential part of the city. While the E Line has 14 stops north of N 65th Street, only three stops serve a long distance before reaching Roy Street. That arrangement skips over entire neighborhoods.

The report misses a critical opportunity for additional transit stops, currently lacking transit needs, and new transit investments that would better connect and serve Fremont, Wallingford, Queen Anne, and South Lake Union.

Aurora Bridge and Woodland Park are ignored

Two of the corridor’s most dangerous and constrained areas — the Aurora’s George Washington Bridge (spanning the Fremont Cut) and the narrow Woodland Park segment — are explicitly excluded from concept development.

These are critical connectivity gaps:

- Both are unsafe for cyclists and pedestrians, with high-speed traffic

- Neither have dedicated bus lanes

- The Woodland Park segment lacks access from Aurora

Their omission signals that the study is not ready to deal with the hardest challenges, which need to be solved early if the corridor is to work as a continuous spine. At a cost of $3 million, SDOT’s flawed study cannot be the basis to design Aurora’s future. This report lays the groundwork for a path heading in the wrong direction and the agency needs to overhaul its evaluation before it can properly overhaul its most deadly roadway.

Carlo Alcantara co-leads the Aurora Reimagined Coalition. Follow him on Bluesky at @olraca.