In a whirlwind session Monday morning, members of the Seattle City Council got their first full look at over 100 potential amendments on deck for the city’s 20-year growth plan ahead of its final adoption this fall. With councilmembers submitting changes independently of one another, for the most part, the meeting kicks off a month of negotiations that will determine which proposals have majority support. On the list are tweaks to proposed growth center boundaries in individual neighborhoods, along with broader tweaks to city policies and specific incentives intended to promote specific types of housing.

Due to public notice requirements, no more amendments can be considered. So, this list now represents the full universe of changes that could be made to Mayor Bruce Harrell’s One Seattle Plan.

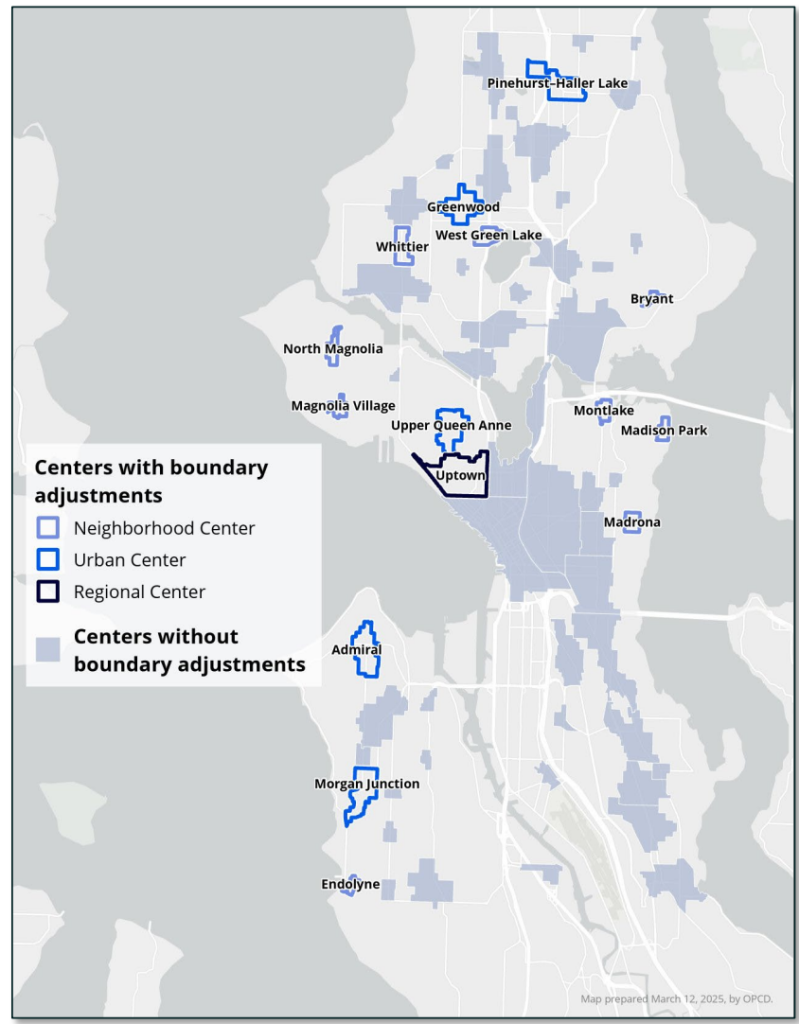

When finalized in September, the council will be approving final zoning regulations in the city’s lower-density residential areas, in the wake of temporary regulations adopted this spring. They’ll also be approving the boundaries for the planned neighborhood centers, areas of increased housing capacity around existing commercial business districts.

However, official zoning designations for those areas won’t be fully approved until next year, when they adopt the plan’s second phase. In other words, only which blocks are within neighborhood centers is on the table right now, with details like building heights and density limits left for later.

Across the 106 amendments, there are some big themes councilmembers are going to grapple with as they try and find something that approaches a consensus.

Citywide changes to incentivize stacked flats, affordable housing, or family-sized units

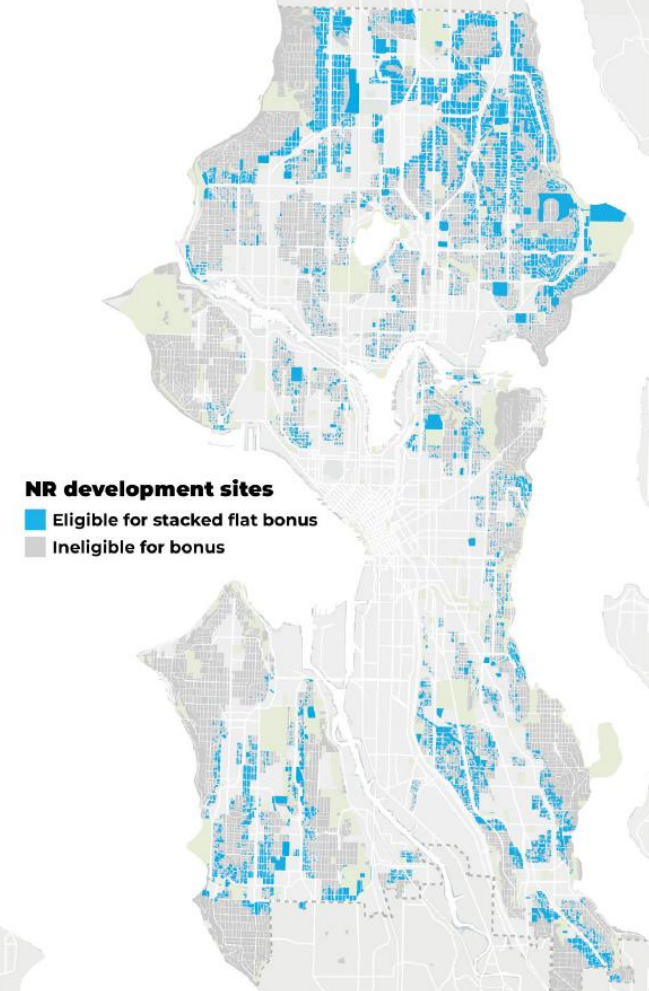

A major theme within amendments is potential tweaks that provide density incentives for building specific types of housing. Numerous councilmembers put forward incentives for stacked flats, modifying the proposed density bonus proposed by the Harrell Administration that would have applied to lots exceeding 6,000 square feet if builders stack units on top of each other. As it stands, the proposed stacked flat bonus would mostly have applied to lots in the city’s far north and far south, leaving out many areas close to frequent transit and major amenities.

An amendment from Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth would lower that minimum size to 5,000 square feet, while amendments from Council President Sara Nelson and Councilmembers Bob Kettle and Alexis Mercedes Rinck would remove it entirely.

Nelson also proposes removing a restriction on another density bonus program — letting affordable housing providers build denser even if they’re located away from a frequent transit route. She also proposes a new density bonus program for the city’s low-rise (LR) zones, providing additional development capacity if builders set aside 25% of units as affordable to households making 60% of the county’s median income when renting, or 80% if owning. This would be a move similar to Rinck’s Roots to Roofs pilot program, but with less density and applied broadly across the city.

Rob Saka proposes giving cottage housing developers more flexibility, granting additional lot coverage allowances and bringing cottage housing up to the same maximum density limits as stacked flats.

Several amendments also include social housing in the city’s affordability bonus program, when it wouldn’t otherwise qualify given the model of providing mixed-income development. Both Hollingsworth and Kettle would extend the proposed affordability bonus program to social housing, granting the Seattle Social Housing Developer the same incentives as a non-profit developer.

Hollingsworth also has an amendment to grant additional development capacity for builders who want to build units with at least three bedrooms within a quarter mile of a school. And an amendment incentivizing developers to build more units that are accessible to people with disabilities, exempting “type A” accessible units — the most accessible standard — from density limitations. Another Hollingsworth amendment would incentivize the construction of balconies by allowing smaller balconies to count toward amenity area requirements.

Neighborhood center changes

Most of the seven district councilmembers have put forward proposals to tweak the boundaries of the proposed neighborhood centers in their districts, on top of Alexis Mercedes Rinck’s amendment to restore eight centers around the city that were dropped earlier in the plan’s environmental review. Bob Kettle has also proposed restoring the neighborhood center on Nickerson Street that was also included in Rinck’s larger amendment.

On the other hand, several councilmembers have proposed scaling things back, even in the wake of significant cuts to the neighborhood center boundaries as they were finalized and sent to council earlier this year.

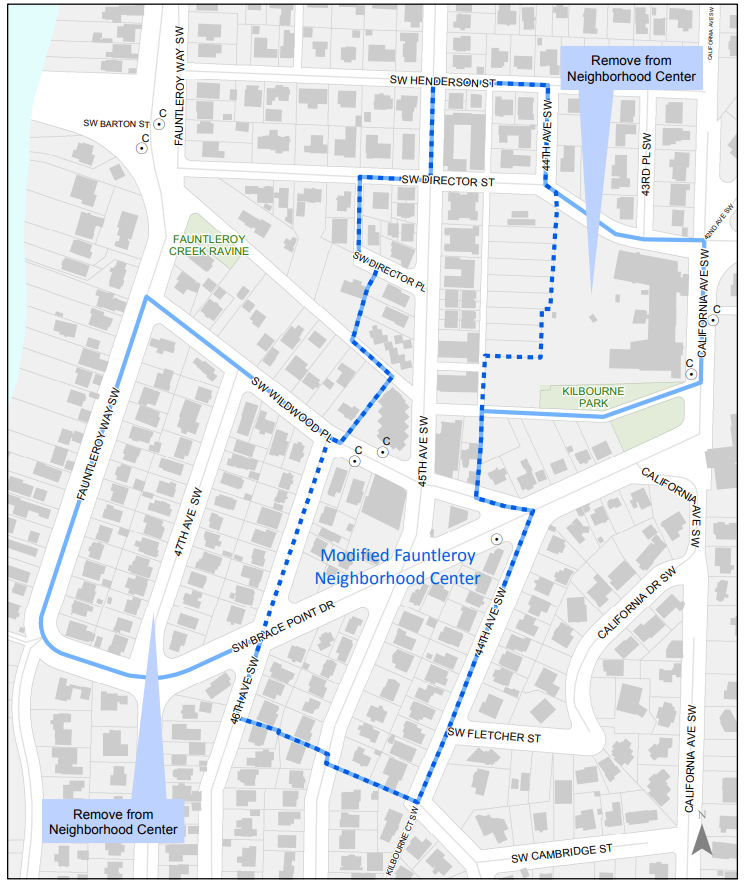

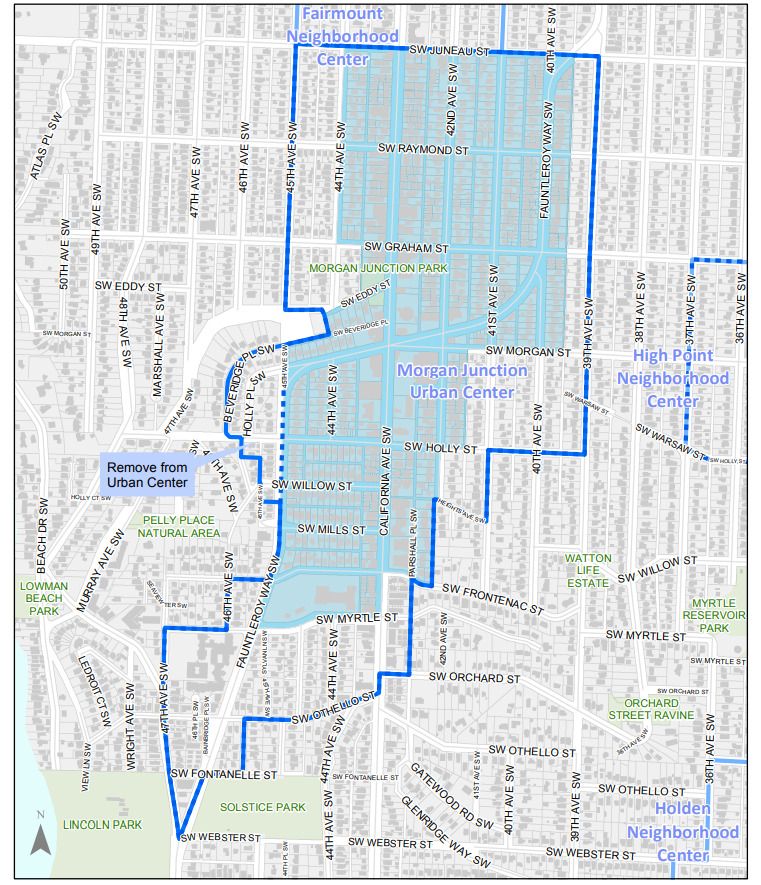

In District 1, Councilmember Rob Saka has responded to pressure to scale back the proposed neighborhood center in Fauntleroy (formerly named Endolyne) close to the Fauntleroy ferry terminal. Members of Fauntleroy’s neighborhood association started a letter-writing campaign in opposition to increased housing density, telling councilmembers that “the unique character of the Fauntleroy neighborhood will be damaged forever if the One Seattle Plan is implemented here.”

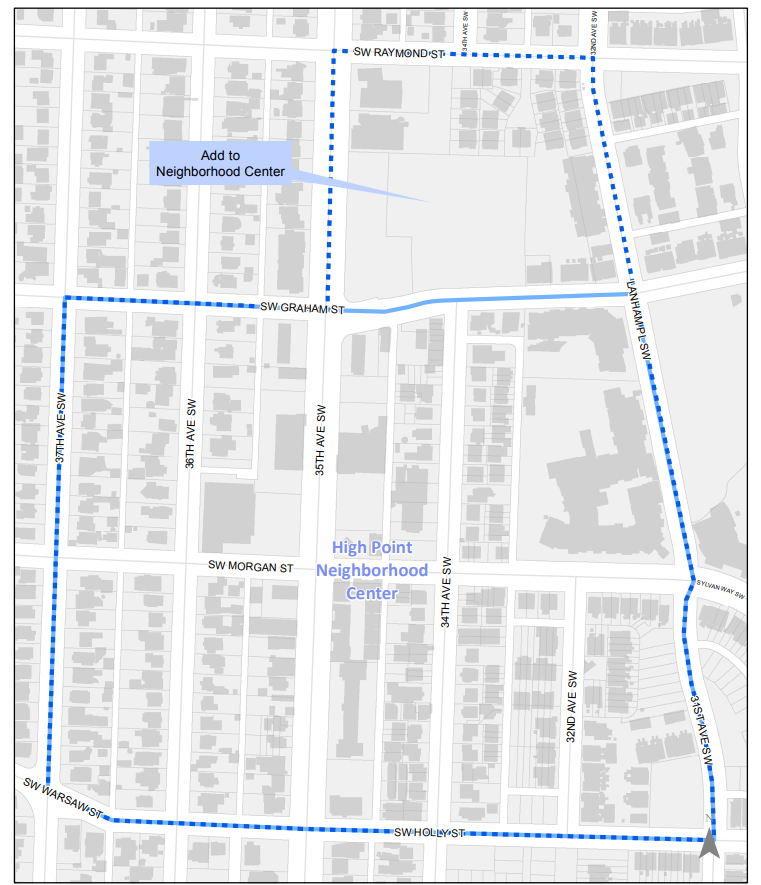

Saka responded by proposing a removal of two large blocks from the center, shrinking the potential of the new center to create a new neighborhood around the existing small business district. Additionally, he proposed to scale back the proposed expansion of the Morgan Junction urban center by around one block, and to expand the High Point neighborhood center by one block.

District 2 Councilmember Mark Solomon hasn’t proposed any changes to the neighborhood centers in his district, instead only putting forward an upzone that would impact one block in Columbia City, bringing the zoning there in line with the rest of the urban center.

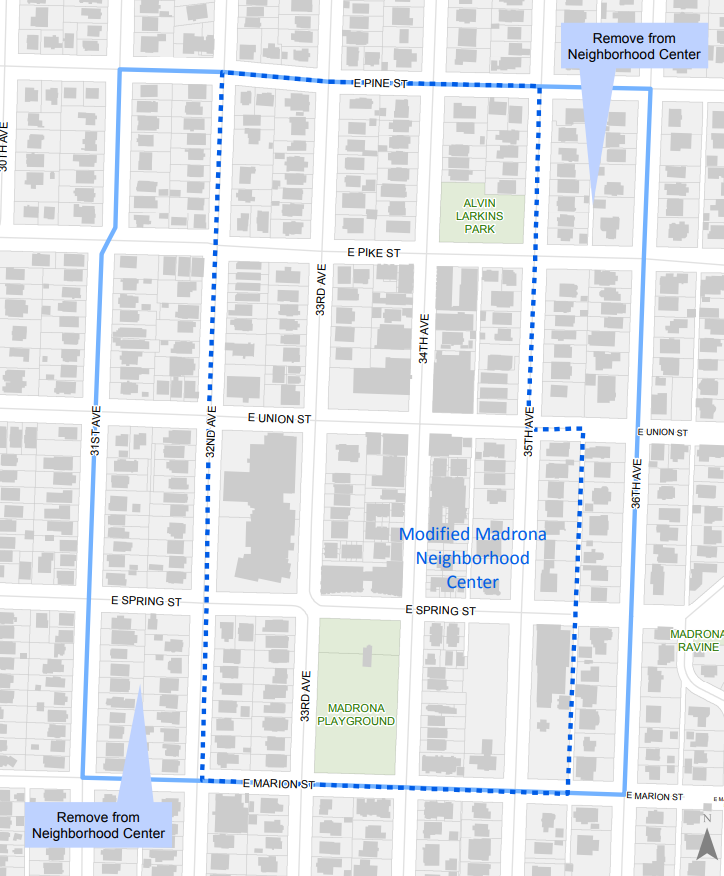

In District 3, Comprehensive Plan Committee Chair Joy Hollingsworth has put forward a proposal to shrink the Madrona neighborhood center by around a third, chopping off blocks to the east and the west of the main 34th Avenue corridor. Madrona has been one of the most vocal neighborhoods when it comes to their neighborhood center.

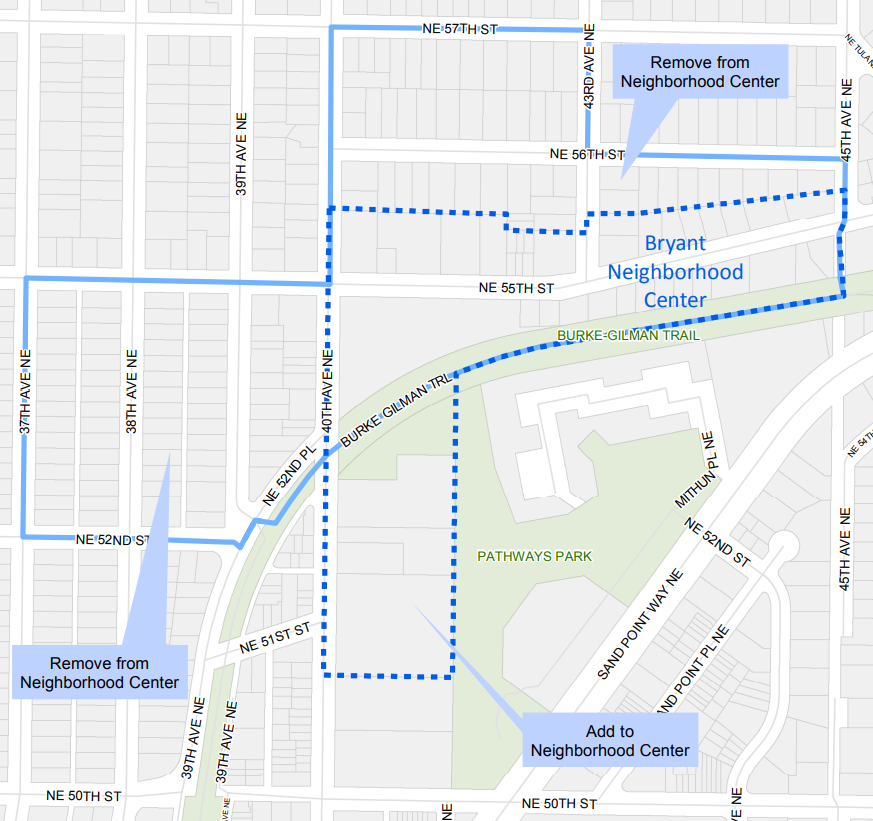

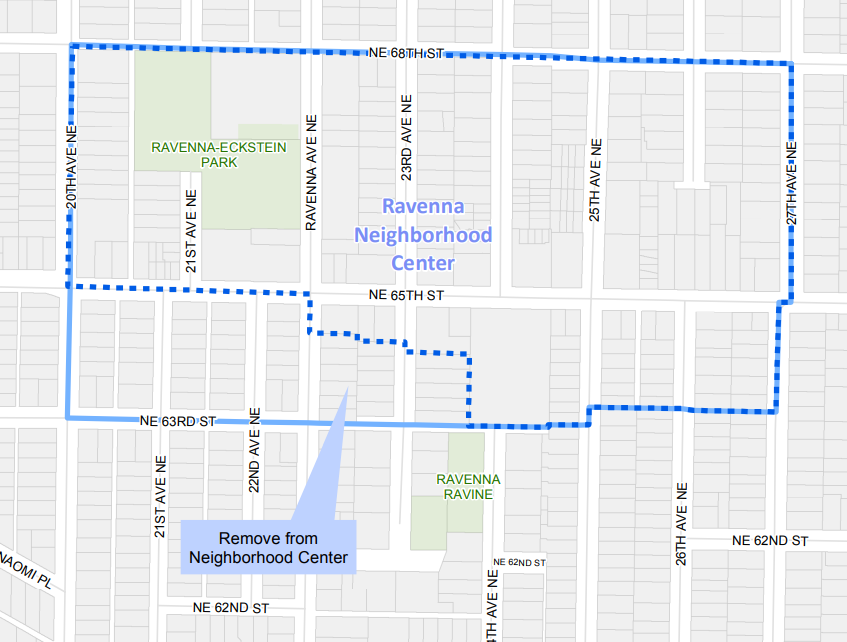

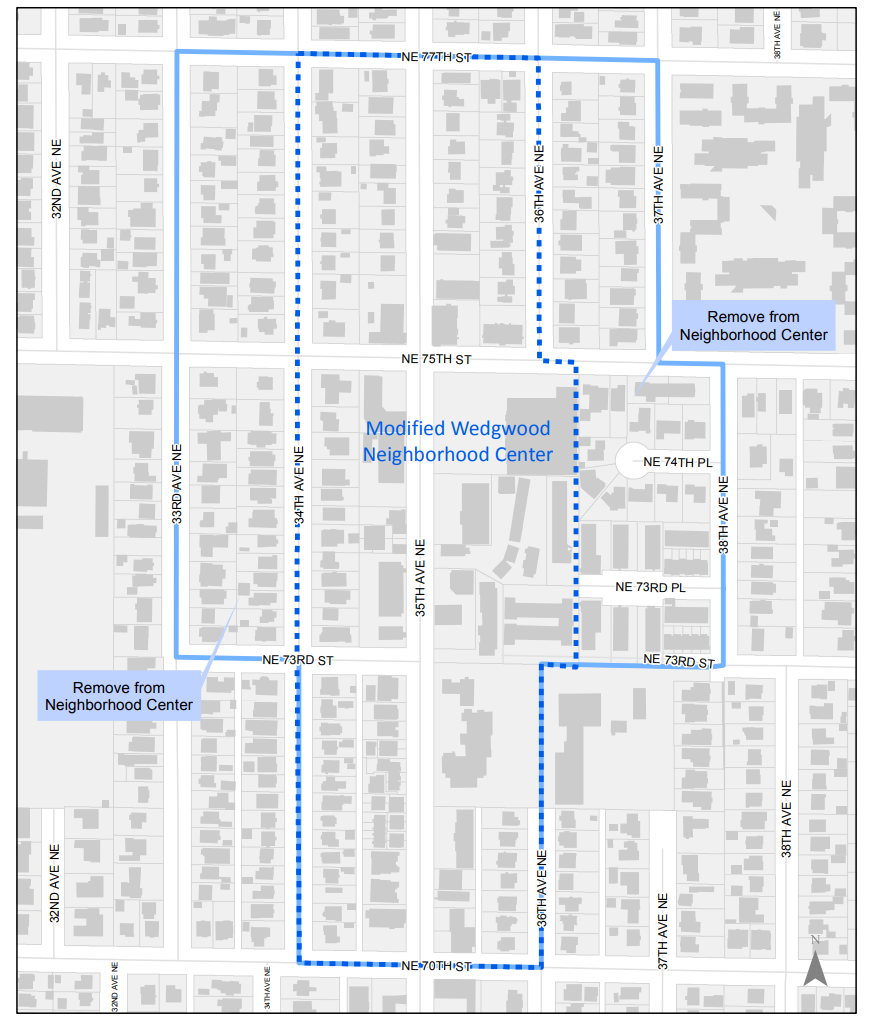

District 4 Councilmember Maritza Rivera took the most ambitious approach in scaling back neighborhood centers in her district, dropping multiple blocks off the Bryant, Wedgwood, and Ravenna neighborhood centers.

Residents in Bryant — and the nearby in the even more exclusive Hawthorne Hills neighborhood — had pushed back vociferously on that center. Among the arguments against increased density in the area was the idea that the 39th Avenue NE neighborhood greenway would be negatively impacted.

In Ravenna, the blocks of the neighborhood center within the Ravenna-Cowen Historic District would also be dropped under a Rivera amendment, giving credence to the idea that increased density and historic character aren’t compatible. Wedgwood, too, would see its boundaries shrink significantly if Rivera’s amendments move forward.

In District 5, newly appointed Councilmember Debora Juarez missed the deadline to be able to submit proposed amendments, and none of her colleagues appear to have been interested in moving forward changes to the neighborhood centers in that district. Despite the fact that former Councilmember Cathy Moore made it clear she wanted to see the Maple Leaf center scaled back — with an amendment doing that reportedly drafted behind the scenes — it did not make it into the final package.

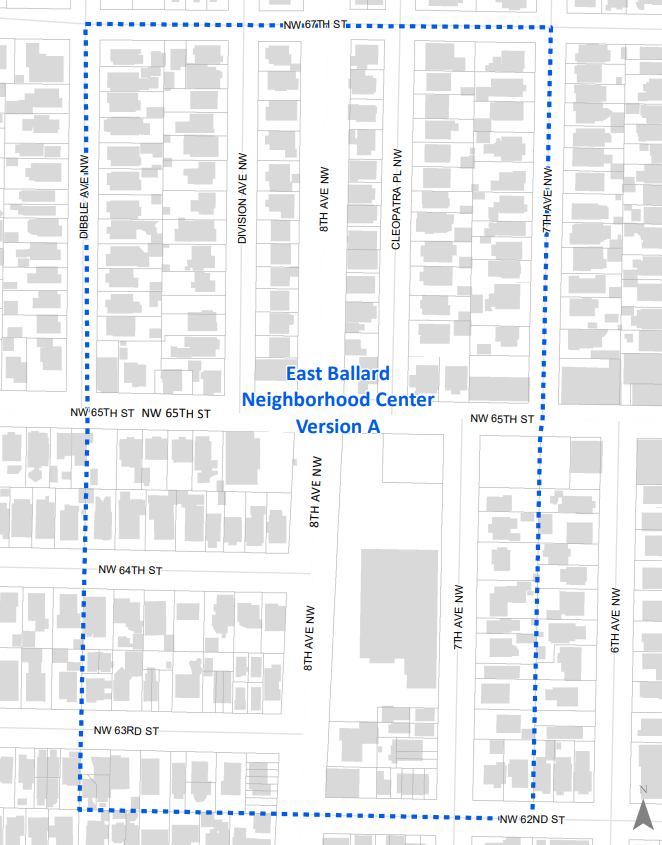

District 6 Councilmember Dan Strauss has proposed three different versions of tweaks to the proposed neighborhood centers in his district, all of which he says maintain a consistent level of increased housing capacity. Strauss also proposes a new district neighborhood center in “East Ballard” — centered around 8th Avenue NW.

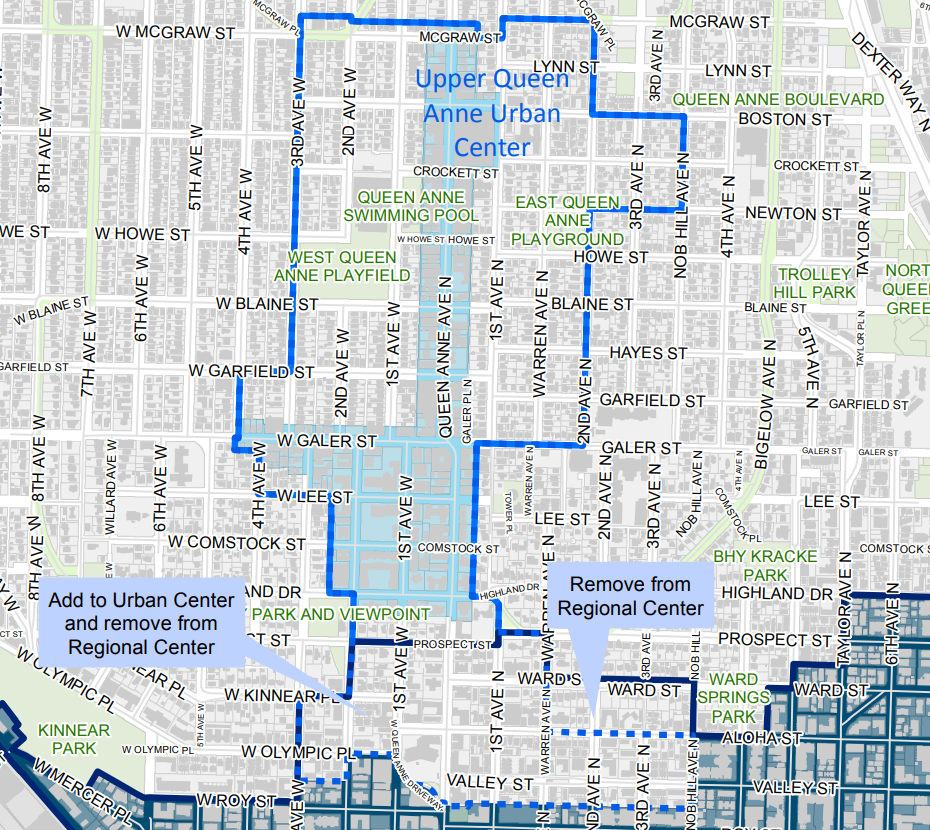

Apart from supporting the new Nickerson Street neighborhood center, District 7 Councilmember Bob Kettle hasn’t proposed any dramatic changes in his district, apart from transferring a small section what is proposed to be expanded within the Uptown regional center and instead transferring that to the Queen Anne urban center.

The topic of trees

The issue of tree retention has become a lightning rod in discussions of Seattle’s growth plans, and multiple councilmembers put forward amendments touching different aspects of tree policy. Most of these came from Dan Strauss, who shepherded the city’s tree preservation ordinance in 2023 that has now come under fire for not doing enough to protect trees during development.

Groups like Tree Action Seattle have decried what they deem “lot sprawl,” in which new development takes up a high percentage of a residential lot, even as Seattle’s reluctance to densify increases pressure on King County’s forest-heavy exurban fringe and sets the stage for actual sprawl. They’ve pushed for the city council to mandate rather than incentivize stacked flats and shared walls, and to reduce the amount of flexibility that developers have to utilize land where housing projects are planned.

Strauss’s most stringent amendment would ban builders from removing large, valuable trees from within five feet of the edge of a lot, essentially imposing a setback requirement anywhere there are currently large trees. He also proposes to grant flexibility whenever builders are preserving trees, allowing structures anywhere within a setback where they otherwise couldn’t be allowed. That amendment would also allow a reduction in the required “amenity area,” i.e. a courtyard or front yard, if trees are preserved on site.

Strauss also has an amendment to require builders to plant at least one tree for every 2,500 square feet of development, which would be a change from the Harrell Administration’s proposal. In effect, Strauss would require more trees for lower density projects that come with fewer new homes.

Maritza Rivera, taking tree preservation to an extreme, has put forward an amendment that would empower Seattle’s building department to require architects and developers to create alternative site plans that would result in preserved trees. Under the amendment’s language, if any alternative building plan could “increase the retention of existing healthy trees, advancing the City’s canopy, environment, equity, public health, and climate resilience goals” then the city could require a full configuration in order to receive a permit. And it wouldn’t just apply to Tier 1 and Tier 2 trees — the largest and most valuable under the existing tree code — but any trees.

Rinck also has an amendment that would allow developers to opt out of parking requirements if they preserve large trees on site, though that amendment clearly wouldn’t be needed if there’s a larger appetite to fully tackle the issue of abolishing parking mandates entirely, as she’s proposed.

Now the council has a month to take in all of these proposed changes. The council’s Comprehensive Plan Committee won’t meet again until September 12, when they will hold a final public hearing on the plan and the proposed amendments. Days later, on September 17, 18, and 19 they are scheduled to vote on those amendments, putting their final touches on the plan before adopting it later that month.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.