4 Line light rail would stop well short of urban cores and not open until the 2040s, making a bus rapid transit line a better fit for Kirkland and Issaquah.

Sound Transit promised a new light rail line to serve the growing Eastside cities of Kirkland and Issaquah. But the current plan for the 4 Line skips right past both city centers. Stations are placed on the outskirts of town, tucked into park-and-ride lots far from where people actually live, work, or shop. Service on the 4 Line isn’t expected to begin until 2041 at best or 2044 in the less rosy scenario, and by then, the project risks becoming a costly case study in missed opportunities and misguided planning.

But there is still time to change course. Sound Transit has already studied alternative alignments that could arrive sooner, cost less, and, most importantly, provide better service to both cities.

4 Line provides parking, miles away from any destinations

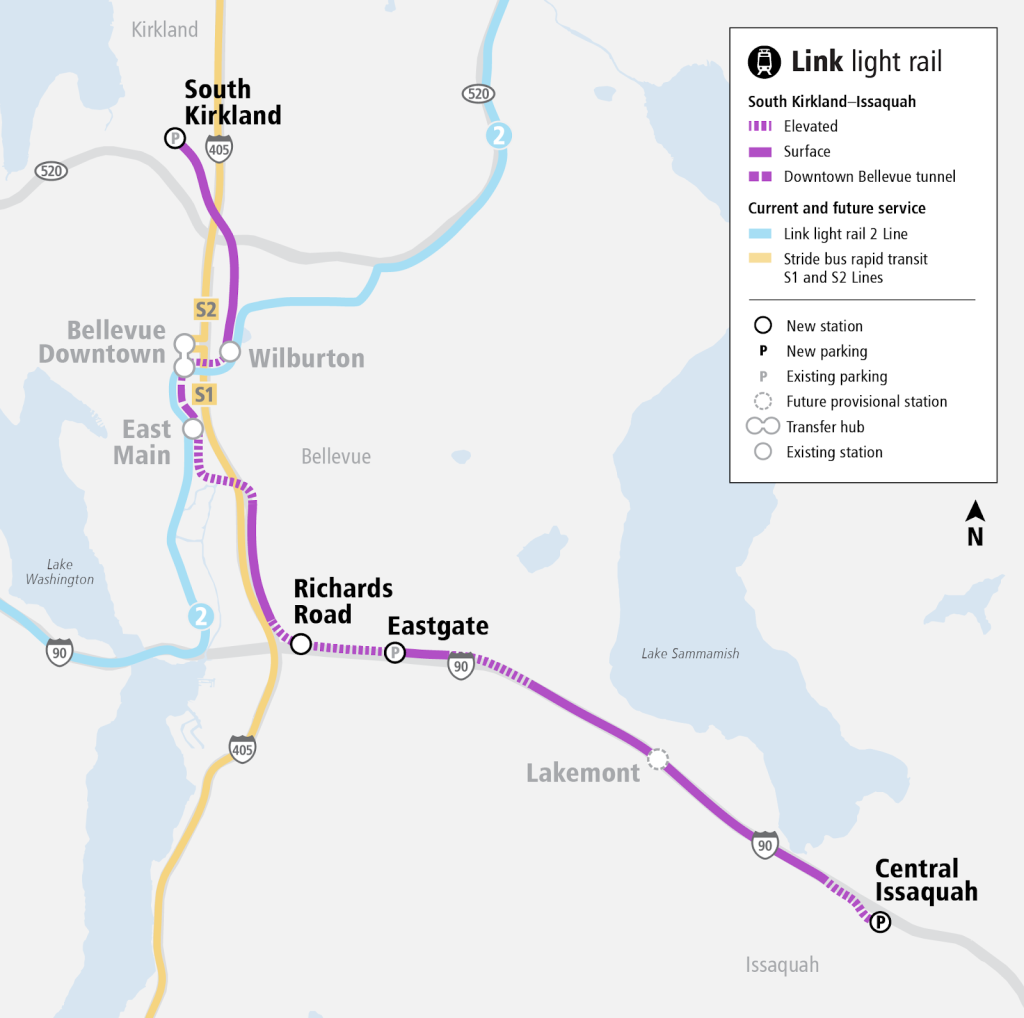

The current 4 Line plan includes just one station for each city: South Kirkland Station and Central Issaquah Station. Neither is remotely central or well situated for the communities they’re meant to serve.

South Kirkland Station is little more than a park-and-ride on the edge of town. While a few apartment buildings sit nearby, downtown Kirkland is an hour’s walk away, and the closest landmark is a Burgermaster drive-in. Burgermaster is a great place to grab a burger, but isn’t the kind of anchor tenant you’d expect at the end of a major light rail line.

Central Issaquah Station is central only in name. Like its Kirkland counterpart, it’s a park-and-ride located on the city’s edge. The station is tucked between strip malls and surface parking lots. It’s a 40-minute walk to the shops and restaurants on Front Street, and a long, uncomfortable trek over the freeway to Costco HQ or Lake Sammamish State Park.

Ballooning costs for shrinking service

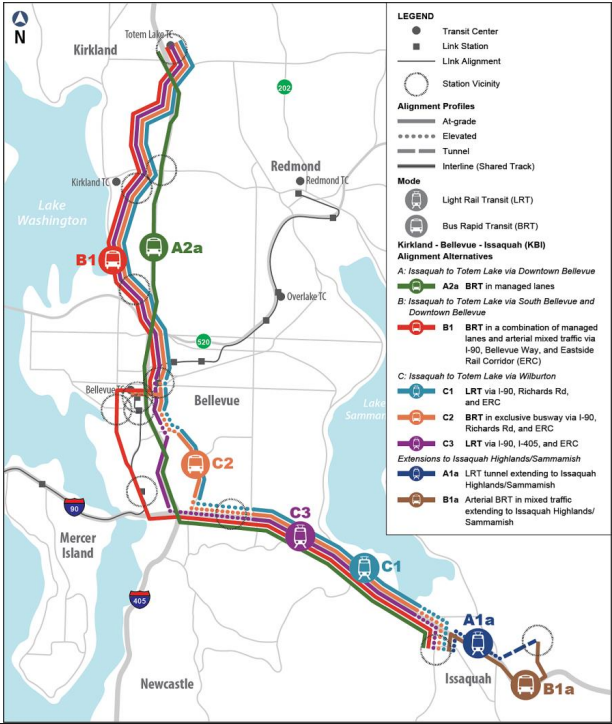

Sound Transit’s early studies explored alignments that would have connected to the rapidly growing areas of Totem Lake and Issaquah Highlands, which would have linked the densest clusters of housing, jobs, and retail in both cities. But those plans were ultimately abandoned as the agency wrestled with the high cost of a longer line and low ridership projections tied to low-density stations.

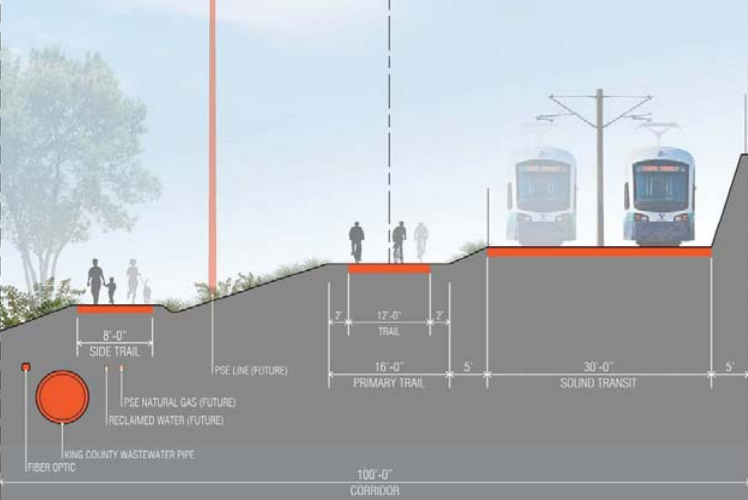

In Kirkland, rail was always going to be a challenge. The Eastrail corridor is the most viable path through the city, but it runs too far east to reach downtown without costly tunneling or land acquisition. Recognizing these geographical limitations, Kirkland officials advocated strongly for bus rapid transit (BRT) as a more flexible and affordable solution. The City funded its own feasibility study, advocated for dedicated transit lanes, and argued for a nimbler approach to serve the city, using right-of-way from the Cross Kirkland Corridor trail.

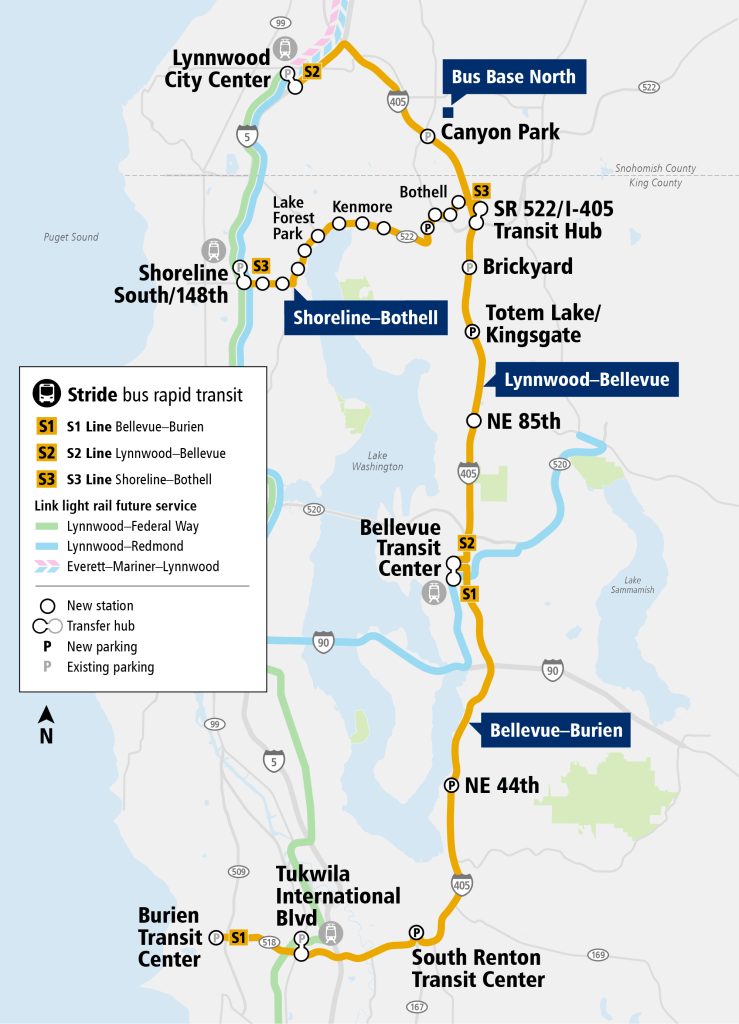

But Sound Transit was less supportive, perhaps fearing that a bus line wouldn’t generate enough Eastside votes or that using trail right-of-way would be controversial with voters given the organized opposition under the Save Our Trails banner. Negotiations broke down, and Kirkland was left with just the light rail station at South Kirkland Park-and-Ride and I-405 BRT.

Issaquah’s rail plans faced similar headwinds. Early concepts imagined a line running through downtown Issaquah to Issaquah Highlands, but those plans were shelved as cost estimates ballooned and ridership estimates sagged.

The current proposal stops far short of Issaquah’s core. Riders from Issaquah Highlands will be relegated to a two-seat ride just to reach Bellevue or a meandering three-seat ride to Seattle. It’s a far cry from the seamless regional access voters were promised.

As currently designed, 4 Line fails to meet the needs of either city, and there is little hope to fix it later. Sound Transit is already approaching its debt ceiling and faces legal limits on its taxing authority. Even if additional taxpayer funding was approved, any future extension would be decades away at best.

History warns us against unfinished plans. The ill-fated Seattle Monorail Project died after nearly a decade of planning and multiple rounds of voter approval. The long-promised connection between the South Lake Union and First Hill streetcars may never be built due to thin support from Seattle officials and soaring costs.

In effect, 4 Line is being built to stop short permanently, not to serve growing downtown cores of Kirkland and Issaquah.

A smarter, faster solution

We don’t need to wait 20 years for second-rate service. Sound Transit still has time to change course. Early studies by Sound Transit have already identified lower-cost alignments that would provide far better service to Kirkland and Issaquah. For a third of the cost, we could get transit that actually reaches where people live and work, and we could build it in years rather than in decades.

To put the numbers in perspective, Sound Transit’s 2014 estimates put the cost of a BRT line between Totem Lake, Bellevue, and Issaquah Highlands at $760 million to $1.01 billion, serving 11,000 to 13,000 daily riders. Building the same corridor as light rail would cost more than three times as much, at $2.41 billion to $3.28 billion, and serve the same 11,000 to 13,000 daily riders.

And yet the version of 4 Line moving forward isn’t even the full corridor. It’s a shortened segment that runs from South Kirkland to the edge of Issaquah. The projected ridership for the entire segment is 8,000 to 9,000 riders, with the vast majority of riders travelling between Bellevue and Factoria. That’s an alarmingly low return on such a large investment.

It doesn’t have to be this way. While rail is unlikely to reach downtown Kirkland, the originally proposed BRT line could. It could follow the Eastrail corridor, exit to serve downtown Kirkland, and continue on to Totem Lake (and potentially even Bothell or Woodinville). The City of Kirkland has already studied how to add dedicated busways to the Eastrail corridor while preserving the trail for people walking and biking.

In Issaquah, BRT could also deliver better service at a significantly lower cost. Sound Transit’s early studies proposed an extension to Issaquah Highlands, which would connect to far more residents while also providing high-quality transit within the city itself. And because BRT is so much cheaper to build, the project could be delivered many years earlier than the current light rail timeline.

These alternatives aren’t speculative. They build on existing planning, align with Sound Transit’s Stride BRT framework, and offer a faster, more effective way to expand our regional transit network without the delays and cost overruns that continue to undermine major projects. Instead of 4 Line joining the Link light rail network, an S4 Line could join the Stride BRT network.

Kirkland and Issaquah deserve better

Sound Transit is grappling with ballooning project costs, mounting delays, and an agency-wide realignment of plans. That means the agency’s expansion projects are likely to get scaled back or pushed even further into the future.

Rather than trimming 4 Line or delaying construction into the 2050s, Sound Transit should seize this opportunity to rethink its approach to serving Kirkland and Issaquah. The current plan doesn’t serve the needs of either city. It doesn’t connect to where people live, work, or want to go. A smarter and more flexible alignment could be built sooner, reach more destinations, and finally deliver reliable regional transit to the two growing communities.

There’s still time to get this right. Residents of Kirkland and Issaquah deserve more than a line that looks good on a map or a station built for a photo op. They deserve real transit that serves their neighborhoods, supports their daily lives, and arrives within their lifetimes.

Oliver Chen

Oliver Chen is a Seattle-based student and professional who is passionate about sustainable and affordable housing and transportation. He first moved to Seattle in 2021 for work opportunities and recently returned to the city after spending two years in Kirkland.