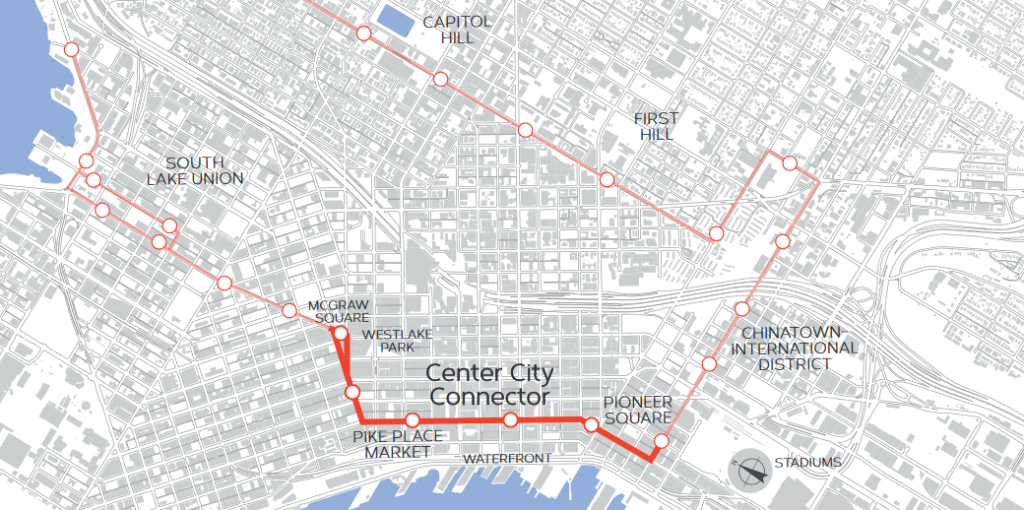

Failing to connect two disconnected streetcar lines could spell a death spiral for Seattle streetcars, which are limping along without the center city link.

Support for building the Center City Connector streetcar appears to be evaporating due to the revelation of another jump in cost estimates on the long-stalled project. Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell had included the streetcar extension — rebranded as the “Cultural Connector” — in the original version of his Downtown Activation Plan this past summer. However, recent presentations of the plan have erased mention of the streetcar.

The Harrell administration has emphasized the “huge” price tag and the City’s looming budget deficit, which is estimated at nearly a quarter billion dollars annually. The deficit went unaddressed in Mayor Harrell’s most recent budget, which sidestepped recommendations from the City’s progressive revenue task force and did not add new revenue sources. A wave of new centrist leaders elected (and appointed) to Seattle City Council have also emphasized budget discipline and cuts rather than raising new revenue.

“So the price tag is huge,” Harrell told The Urbanist last Wednesday. “And because we are calling it the cultural connector did not signal my lack of interest in trying to spin it. I think some people thought that, well, it’s losing momentum. I would absolutely love to have a streetcar connector. But I have to tell you that you we have to close the scrutinizing numbers involved. And those numbers were very, very high. And so working with our transportation department work with our engineers, we will make some tough decisions this year.”

While the report released last month estimated the project would take $410 million to build — up 43% from the 2019 estimate of $286 million — it included a number of promising suggestions to trim costs. For example, pedestrianizing a section of First Avenue from Yesler Way to Jackson Street in Pioneer Square would save about $17 million while also improving the environment for pedestrians and street cafe-goers. If Seattle were to take a cue from successful European trams (which are commonplace), this is how they would build the project, improving outcomes while saving costs.

Using lighter streetcar vehicles would also reduce the need to reinforce aging streets in Pioneer Square, which were long ago elevated to get out of the muddy tideflats and urban refuse below, as showcased in popular underground tours of the neighborhood. On the other hand, reinforcing century-old areaways and supports holding up Pioneer Square isn’t without it’s ancillary benefits (e.g., reducing chance of collapse or damage in the next major earthquake). In all, the recent assessment estimates $51.6 million would need to be spent to upgrade Pioneer Square’s areaways if using the heavier vehicles deemed easier to procure than the earlier specifications.

However, seeming to view the costs as insurmountable at this time, Harrell and his team seems to have shifted attention to devising alternatives to the connector project.

“[We] still just sort of scratched the surface of the enormous cost of this still may incur,” Harrell said. “And again, the issue for me is if the streetcar connector as planned and as talked about in the last a couple of years is not feasible, we will ask the question are what are alternatives to trying to bridge, I use the term stranded investments where they connect? What are all the alternatives? So basically, a short-winded way of saying that is: everything’s on the table.”

Both Harrell and Senior Deputy Mayor Tim Burgess noted they had read Danny Westneat columns in The Seattle Times haranguing the South Lake Union streetcar. Westneat proposed that Seattle emulate Bellevue’s free ridehailing app geared toward shuttling tourists around downtown, replacing mass transit with an Uber-like product. On Tuesday, Burgess seemed to indicate they were looking into Westneat’s idea.

Burgess also noted the Cultural Connector linear entertainment district concept popularized by Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) Director Greg Spotts and the mayor could proceed independent of the streetcar project, and noted that the mayor intended to announce a decision on the streetcar before the end of the year.

“Nothing’s changed yet. The project is still paused. We’re looking at options,” Burgess said. “What’s not paused is the idea of this linear arts, culture, and entertainment district that still stands and is still one of the mayor’s priorities, whether the streetcar is done. But I don’t think we’re ready quite yet to talk about a definitive decision on the streetcar.”

Nonetheless, it’s not clear that an app, a bit of advertising, and maybe an Uber discount or shuttle count draw people into the neighborhoods along the corridor between First Hill and South Lake Union — Yesler Terrace, Chinatown, Japantown, Little Saigon, Pioneer Square, and Pike Place Market — as effectively as a streetcar literally carrying an estimated 11,000 people daily.

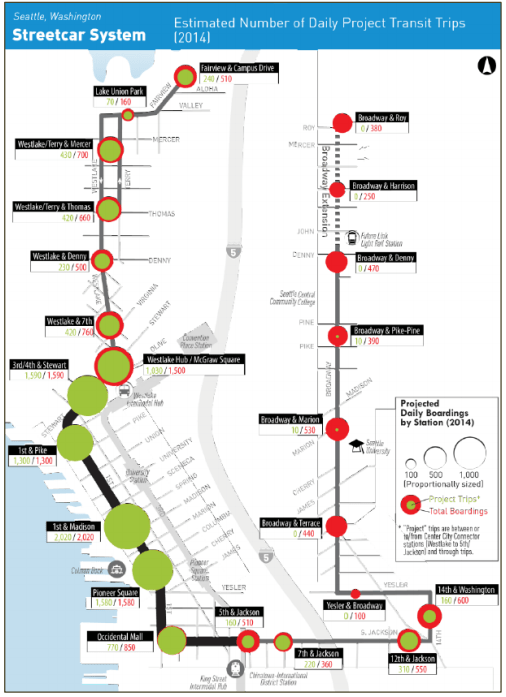

It’s simply urban geometry; streetcar vehicles can carry far more people than a ridehailing shuttle vehicle. For example, the CAF Urbos streetcars envisioned in 2019 can carry up to 166 people each and relatedly weigh about 40% more than the smaller, older model the City uses. The recent assessment continued to find robust ridership projections, taking the completed five-mile-long streetcar network past 11,000 daily boardings. For reference, the region’s highest ridership bus route, the 12-mile-long RapidRide E Line, averaged 10,300 daily boardings according to Metro’s 2022 system evaluation.

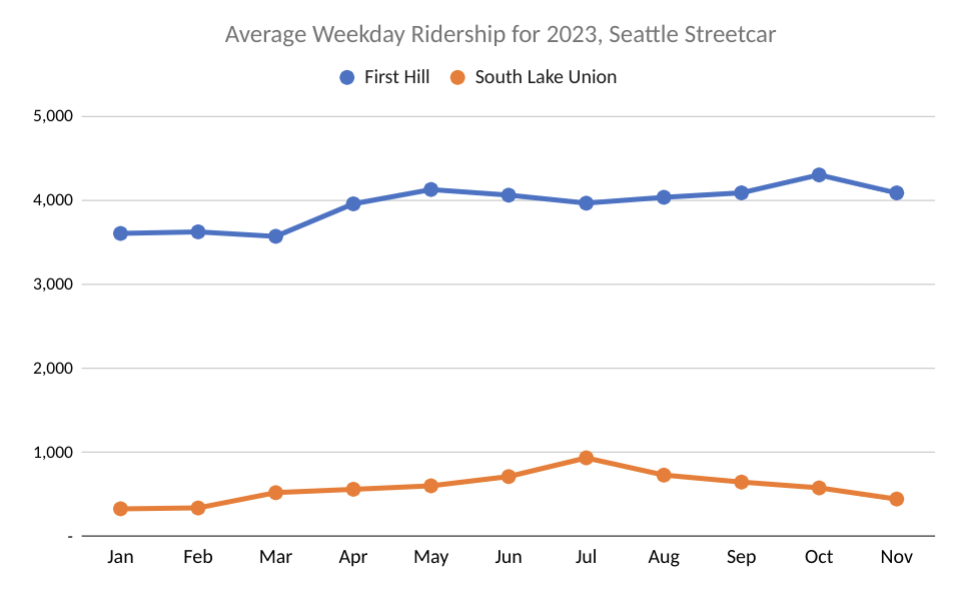

Ridership on the 1.3-mile South Lake Union Streetcar has been anemic in the pandemic era, with riders often preferring partially overlapping bus routes that arrive more frequently. The line averaged about 500 daily passengers in 2023. On the other hand, the longer 2.5-mile First Hill Streetcar trended above 4,000 daily riders in 2023, and even streetcar skeptic Westneat granted it should stay around. As a replacement for today’s floundering South Lake Union Streetcar, Westneat’s shopping shuttle idea almost makes sense. However, a ridehailing shuttle is incredibly ill-equipped to replace a completed streetcar network in the downtown core.

Nonetheless, the City finds itself at awkward crossroads. Without the missing 1.2-mile Center City gap in the middle of the network, the outlook for the streetcar system appears bleak, with no clear plan to fund operations going forward. The perception that existing lines are struggling makes it harder to build political support for the Center City extension.

Financial support from Sound Transit to build and fund the first decade of First Hill Streetcar operations (negotiated as part of abandoning the First Hill light rail station as Link expanded north) expired this year, leaving a $5 million hole in the budget. Anemic ridership on the South Lake Union line and low fare compliance on the First Hill line mean farebox revenue is modest.

Treated as a completely separate service by King County Metro, the Seattle streetcar gets no operational funding from the county agency unlike other transit services, like busses and electric trolleys do. Barring a political miracle, a solution will need to come from the mayor and city council, who have backfilled gaps in the operations budget with commercial parking tax revenue. It appears the City of Seattle will need to dig even deeper in that bucket (and potentially others) to keep the streetcar operating. By 2028, the City projects $12.9 milion per year will be needed just to keep the two lines running.

The renewal of Seattle’s transportation levy, which could be a $1.7 billion package if recent SDOT polling is any indication, could present an opportunity to start topping up the streetcar project coffers. However, the poll didn’t ask about the streetcar, which adds to general picture that the streetcar is languishing on the backburner. Nine years ago, when the City Council debated the composition of the Move Seattle Levy, they approved an amendment banning spending on new streetcars, thanks to ardent streetcar skeptic Nick Licata.

Strident advocates for the streetcar project appear to be dwindling, with few offering a helping hand as the streetcar seems to be lurching toward death’s door. The Downtown Seattle Association (DSA) has long listed the project among its transportation priorities. However, when recently asked for their streetcar position and levy priorities, DSA President Jon Scholes pointed to Third Avenue street improvements, long a dream of his organization.

“Connecting our existing streetcar lines and fulfilling the promise of a functioning network rather than disparate lines remains a good idea,” Scholes told The Urbanist. “We need to ensure people can not only move through downtown but also are able to get here easily and efficiently. The upcoming transportation levy is an opportunity to invest in Third Avenue, our city’s busiest transit corridor. We need to significantly improve the experience of Third, to make it functional and welcoming rather than a place people avoid.”

A lot can change in a year. Last year, the Seattle City Council was laden with anti-streetcar firebrands including Lisa Herbold and Alex Pedersen, who have since retired. The crop of leaders elected to replace them were generally careful to say they were open to the streetcar and even supportive. Being open to an idea is not the same thing as leading and investing the political capital to make it happen, which sums up the last five years of streetcar limbo.

Had then-Mayor Jenny Durkan not paused project construction in 2018 and sent the project to planning purgatory, the Center City streetcar would likely already be in operation today. Since Durkan shelved the project, inflation has been high, especially in the construction sector where numerous projects have seen huge cost overruns. It’s not surprising to see streetcar costs have risen.

Harrell was elected to replace Durkan promising to unite Seattle around big, bold ideas. His plans speak of “Space Needle Thinking” rather than playing small ball.

Rolling out his Downtown Activation Plan in June 2023, a Harrell spokesperson said the Downtown Activation Plan “will present ambitious Space Needle Thinking concepts to reimagine what a Downtown can be and spur community conversations about significant civic projects that represent Seattle’s innovative spirit and would create a world-class urban hub for future generations.” The first bullet point in the Space Needle Thinking section of the plan’s factsheet was: “Develop a linear arts, culture, and entertainment district Downtown, securing funding to complete a connected streetcar route bringing together existing streetcar lines in South Lake Union and Capitol Hill that transports residents, workers, and visitors through the heart of Downtown.”

In our Space Needle analogy, the Center City “Cultural Connector” Streetcar is the elevator. Can a Space Needle run without an elevator? That’s what activating a linear culture district without a connected high-capacity transit line to undergird would seek to find out. But eventually after climbing all 846 steps to the top enough times, people generally tend to ask if an elevator could have been an option.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.