Today the City of Seattle is celebrating the grand opening of the newly remade central waterfront, cutting the ribbon on more than a decade of work to transform one of the city’s most visible public spaces. For a corridor that used to be home to an elevated highway separating the waterfront from the rest of the city, the changes undeniably represent a major upgrade from the Alaskan Way of old.

But with pedestrian amenities and bike facilities attached to a widened roadway, which expands to nine lanes (including parking) near Colman Dock to accommodate ferry queuing lanes, many Seattle urbanists have mixed feelings about the project. While many focus on the number of car lanes built, others lament different missed opportunities presented with such a major project. The narrow and windy protected bike path along the corridor, for example, might have been built very differently if it were being designed today.

Other elements were dropped from the project so long ago that most park visitors today never even knew about them.

The festival pier

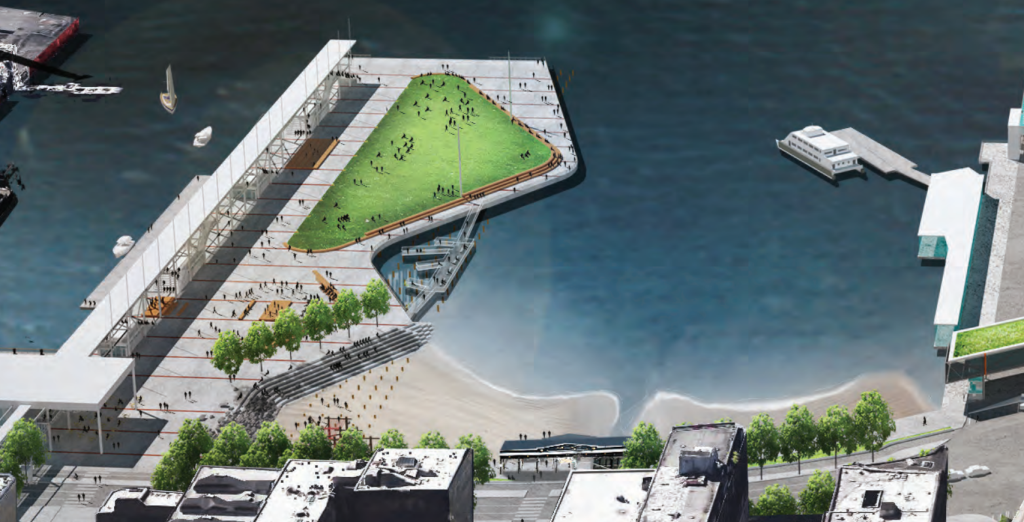

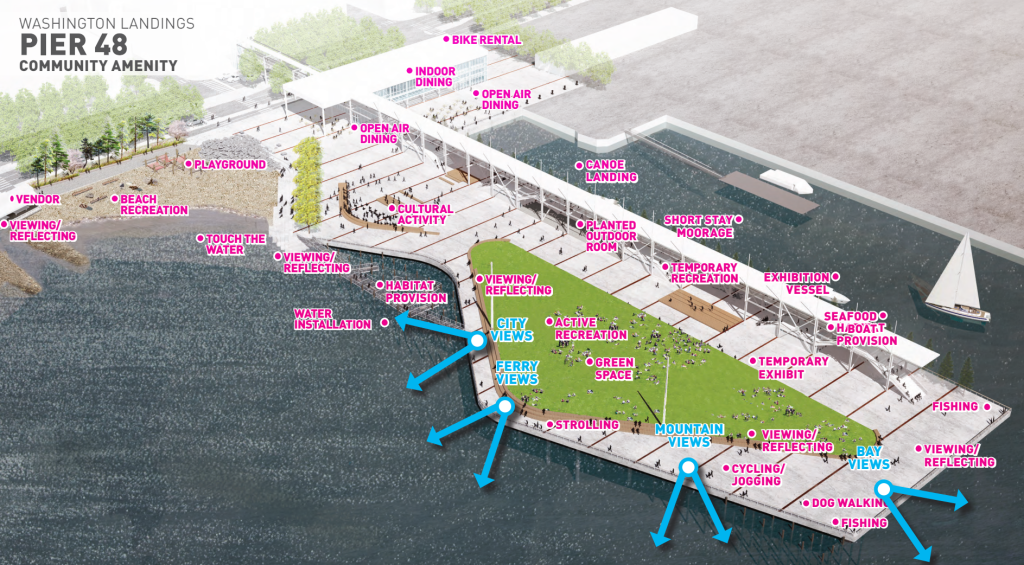

Just to the south of King County’s passenger ferry terminal at Pier 50 is an overgrown pier, sitting in disrepair. Pier 48, owned by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), may have a future as Kitsap Transit’s dedicated fast ferry terminal, but a decade ago it was envisioned as playing a big role in the transformation of the waterfront.

“Pier 48 offers over four acres of flexible surface in a unique setting, with extraordinary panoramic views. It presents a unique and extraordinary opportunity to provide the community with a large public open space on the Seattle central urban waterfront with a variety of recreational amenities and event venue for all seasons,” read an October 2015 presentation to the Seattle Design Commission. “The existing pier is structurally unsound and needs to be rebuilt to take advantage of these opportunities.”

As a parcel not owned by the City of Seattle, Pier 48 wasn’t included as a “core” waterfront project, but ambitious designs were created for what the pier could become, as the largest over-water structure in the area. At over four acres, the pier was envisioned as being the waterfront’s largest event venue, accommodating 6,000 attendees or more. The venue would have been a nod to history; Nirvana performed one of its most famous shows at Pier 48.

The vision was broad and ambitious: an indoor headhouse building that could accommodate events year-round, multiple outdoor event spaces, boat moorage, and a direct connection to a waterfront beach, separate from the planned habitat beach near Pier 50. None of these elements moved forward at all.

The City of Seattle has signaled that it wants to take another swing at including public space improvements with any redevelopment of Pier 48, including the project on its long list of things to be tackled as part of Bruce Harrell’s Downtown Activation Plan. However, the 2024 progress report on the plan noted that work was not yet “in progress.”

While any final plan is almost certain to be less ambitious than the festival pier idea, there’s still a major opportunity to add another amenity to the Waterfront Park’s busy southern end, where the new Molly Moon’s ice cream shop at Washington Street Boat Landing has proven to be a big draw.

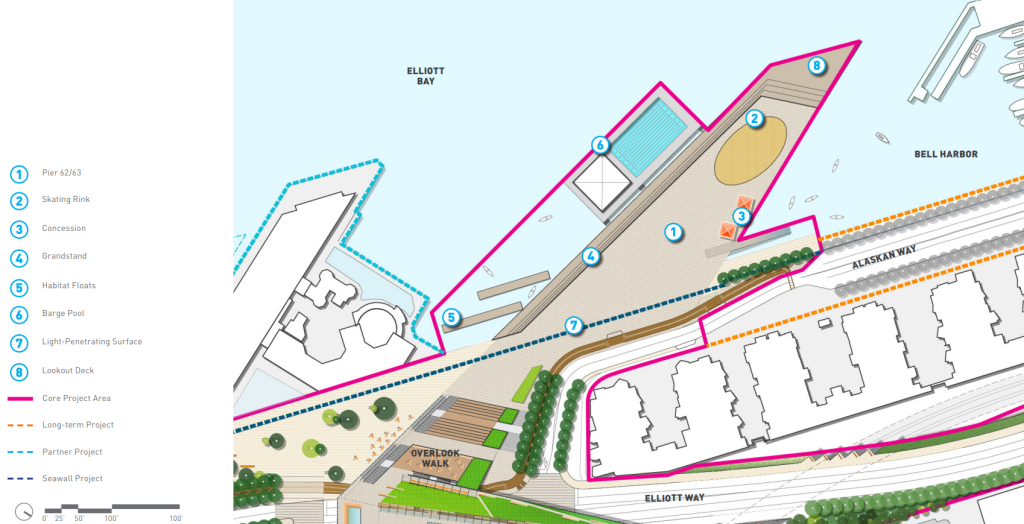

The barge pool

One major project element that had been included among the “core” project elements was the idea of a pool barge attached to Pier 62. More common in Europe, the idea of building a floating public pool was sparking interest across the U.S. at the time of the waterfront plan’s development. Nonetheless, the City dropped it from the plan in 2014, blaming high cost estimates.

“With an estimated price tag of between $22 million and $23 million, the boat was described as an ‘anchoring element’ in a schematic design released earlier this year. It would have featured not only a six-lane lap pool, but also hydrotherapy spas, a locker room and snack bar,” Crosscut noted in 2014.

“While the pool barge was loved by many and received a very positive community response in project polls, it was, almost by definition (as feature that could be floated away), not a ‘critical function’ and was ultimately cut from the project,” Berger Partnership, the firm that designed the barge along with Schemata Workshop, wrote on its website after the fact. “Its wonderful absurdity is what makes it special, and the reason it was among the most predominantly featured of all the Seattle Waterfront proposals in local media and periodicals. We dream that the pool barge, by nature of its portability, may once again rise from the bay to assume its rightful place as a treasured icon and experience of Seattle.”

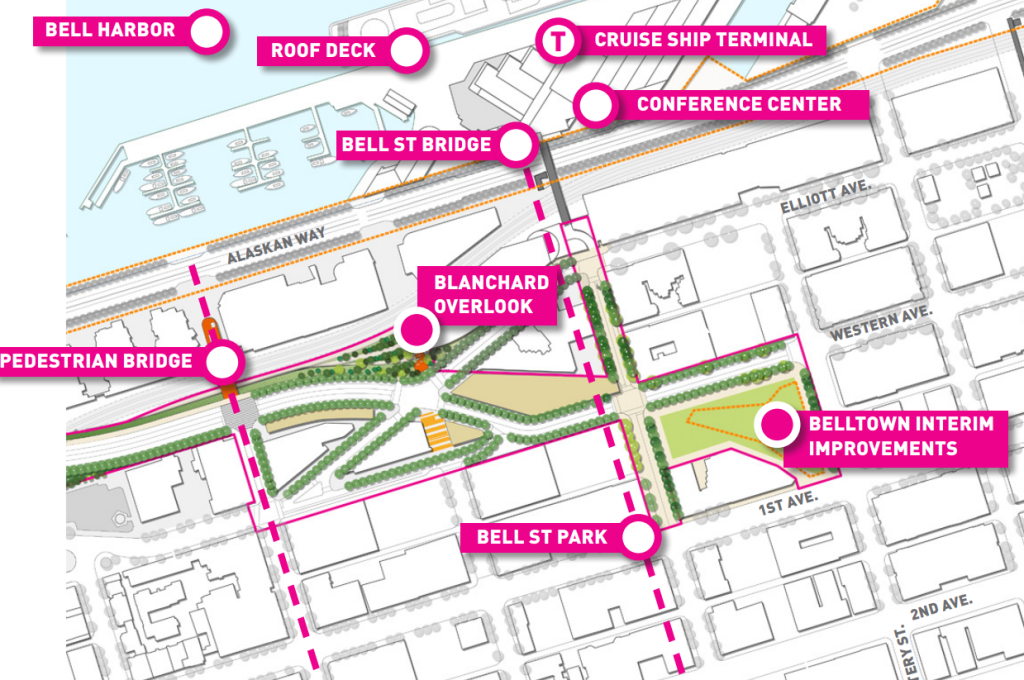

The Belltown bluff

Seattle’s Office of the Waterfront had grand plans for the northern edge of its project’s footprint, finally creating a better connection from the central waterfront to Belltown, one of the densest residential neighborhoods in the state. Ultimately, very few of those plans ended up getting implemented, each for different reasons.

As the city advanced plans for a new Elliott Way roadway that directed freight traffic away from Alaskan Way and its at-grade freight crossing at Broad Street, opportunities to add public space were included in early designs for the project. The centerpiece project in Belltown was set to take shape at the former site of the Battery Street tunnel portal, just north of Bell Street.

While plans for a park on the site did briefly advance, they did so outside the Office of the Waterfront’s work, and in 2021 the City of Seattle announced that it had reached an agreement with Seattle Public Schools (SPS) to hold the site for a potential downtown school. While that deal appears unlikely to be realized in the light of SPS’s financial issues, the fate of Battery Street Portal Park likely won’t be determined until the next round of parks funding is set in 2028.

The Belltown Bluff also included plans for an overlook viewpoint at Blanchard Street, a spot for people to catch great views of downtown and the Belltown waterfront. But that project ran into issues receiving approval from BNSF, which controls the railroad underneath where the viewpoint would have been located.

Concepts were also drawn up for a potential neighborhood playground on a piece of property owned by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) dubbed the “Belltown Opportunity Site.” Those concepts involved pedestrianizing a stretch of street to create a walkway down Blanchard Street, with the playground nestled in beside.

When the playground was cut from the project, the parcel’s fate was thrown into doubt, with the city considering a potential path to creating housing on the site. In 2022, Seattle City Light proposed to build an EV-charging lot on the spot instead. Later that year, the department changed its mind, citing site constraints, and the spot sits unused today.

As the park opens, there’s very little to draw visitors north into the neighborhood and no part of the Waterfront Park extends into Belltown.

Seneca pedestrian street

The waterfront project promised upgrades on a whole slew of east-west streets, and delivered many of them: Pike and Pine Street saw upgraded protected bike lanes, Washington and Main Street saw pedestrian-oriented improvements, and Union Street and Marion Street saw new pedestrian bridges. One street where potential concepts didn’t materialize into a major upgrade is Seneca Street, the former location of a ramp from the Alaskan Way Viaduct.

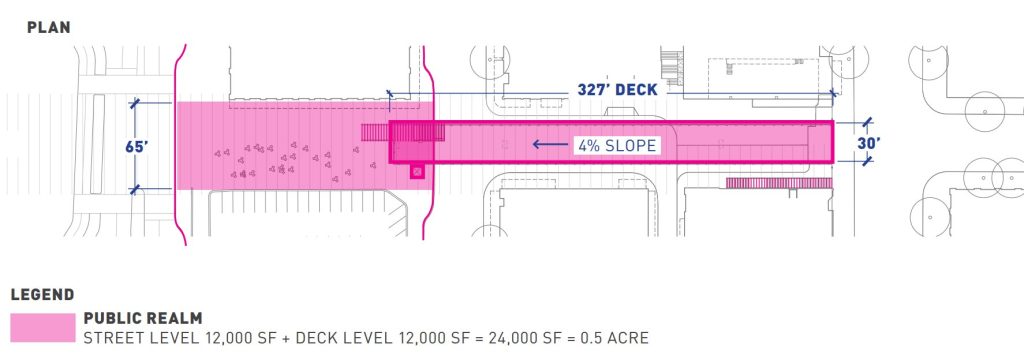

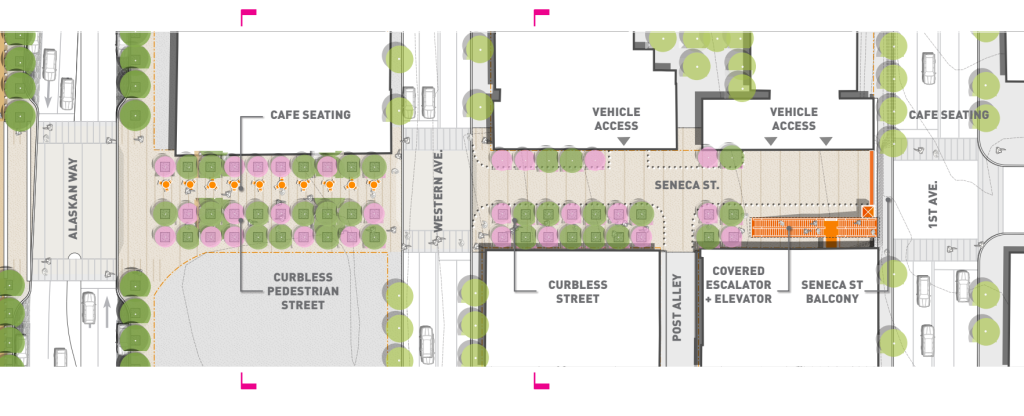

Early ideas for the waterfront included a pedestrian bridge over Western Avenue, mimicking the old highway ramp, with a stairway and elevator connecting to a pedestrianized street on the block between Western Avenue and Alaskan Way.

Eventually this design evolved into a rebuilt stairway and elevator closer to First Avenue, but that concept also included the idea of fully pedestrianizing the street in that section.

“The stairs will land in an alleé of street trees on Seneca Street and lead to a pedestrian friendly environment between Alaskan Way and Western Avenue. This block does not have significant vehicular demands and is adjacent to a great historic building, which has the potential to open at the street level with sidewalk vendors and cafes,” a 2012 presentation noted.

Today, the block is barely noticeable, taken over by back-angle parking and a one-way travel lane. One element of the original design did stay: there are no curbs.

Saturday’s celebration is a well-deserved one and the day will become a notable one in the city’s history books. But the dropped elements that didn’t make it to the point of a ribbon-cutting are a reminder that much work remains to create a people-focused downtown. That more complete metamorphosis will take bold leadership from those steering Seattle into the future.

The Waterfront Park’s grand opening celebration takes place from 11am to 9pm on Saturday, September 6.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.