In the lead up to final public hearing on the long-delayed One Seattle growth plan, opposition has been ramping up to the prospect of denser housing and new commercial storefronts within some of the city’s most popular neighborhoods.

The hearing this Friday, September 12 will be the last chance for members of the public to go on record with their thoughts on Mayor Bruce Harrell’s proposed growth plan, which has been advancing in fits and starts since 2022. It’s also the biggest opportunity for Seattle residents to weigh in on more than 100 amendments that have been put forward by various councilmembers — changes that in some cases make tweaks to encourage more diverse types of housing across the city, and in some cases scale back housing plans.

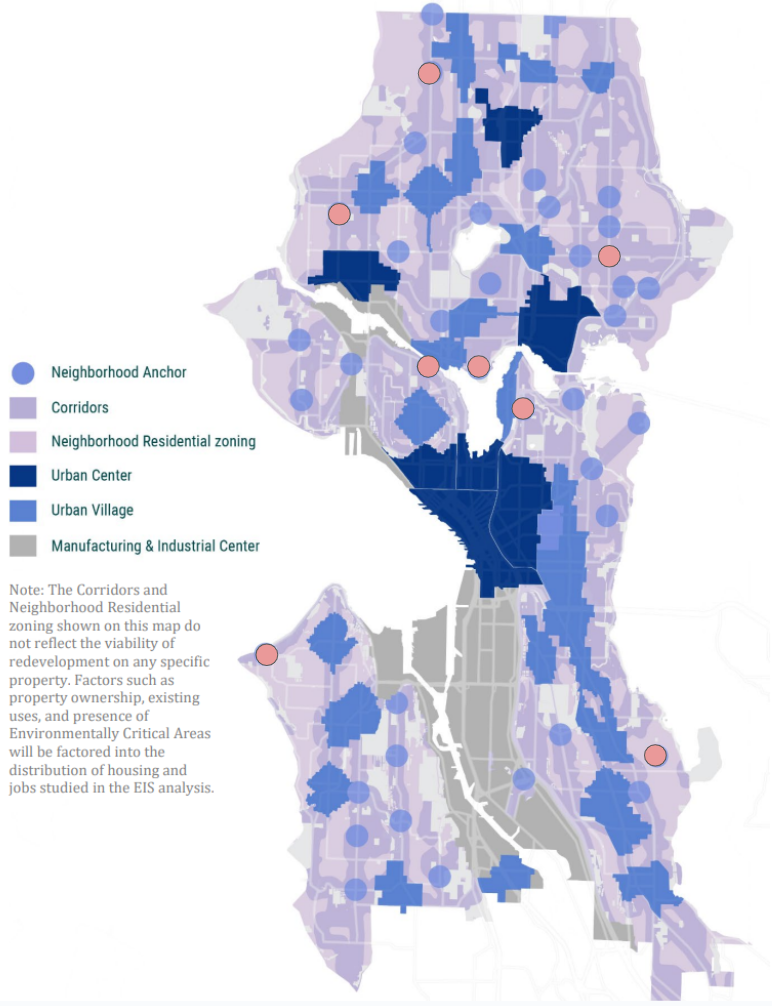

An amendment attracting significant attention is Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck’s proposal to restore eight “Neighborhood Centers” that were included in earlier plan drafts, but later left on the cutting room floor. Those centers, in neighborhoods like South Wedgwood, North Capitol Hill, and Seward Park, would join the other 30 currently proposed as zones of increased development capacity, intended to foster neighborhood amenities and support public transit. The exact zoning for all of those growth centers won’t be determined until early next year.

In recent weeks, opposition to adding those growth centers back has been bubbling up, with Seattle’s community councils acting as a conduit for much of that energy. Dropping at the beginning of August, the amendments apparently caught a lot of groups off guard, coming at the height of summer. Unlike amendments on regular legislation, however, the changes came with a required 30-day notice period, which the council ultimately exceeded.

The new push against adding more Neighborhood Centers comes just as Seattle’s Planning Commission weighs in on the full amendment package, pushing the council to support amendments that either retain or expand those centers centers and other amendments that incentivize more types of housing and small businesses.

“The Planning Commission has been consistent in strongly supporting the creation of Neighborhood Centers. These centers are critical to achieving our vision of a Seattle where all residents live in a great neighborhood that is accessible and connected to the rest of the city and the region,” the commission wrote in a letter approved September 4. “They will serve as a new opportunity for where affordable and accessible housing can be built and are crucial to address Seattle’s history of exclusionary zoning.”

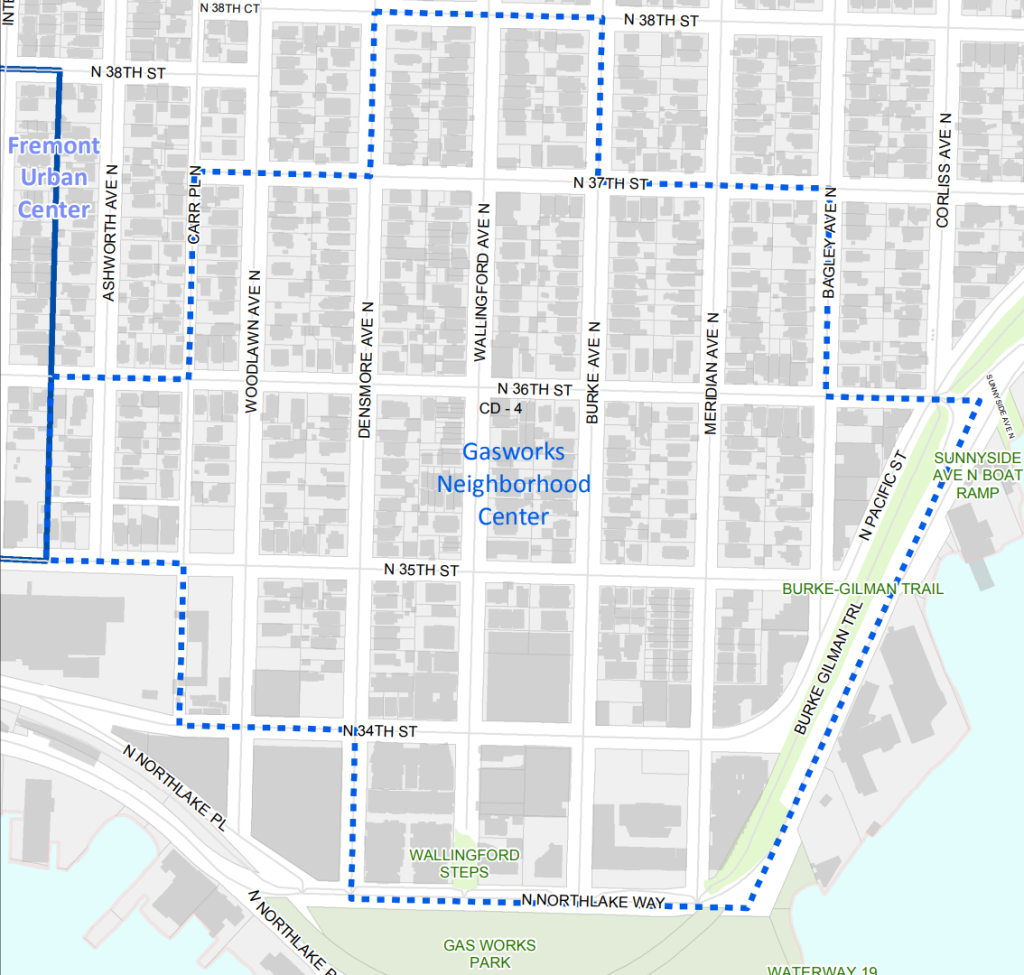

South Wallingford

One Neighborhood Center Rinck’s amendment would restore is located near Gas Works Park, and would essentially extend the existing Fremont Urban Center to cover the area directly north of the popular city park. Directly along the Burke Gilman Trail and close to bus routes 31 and 32, the area seems like a natural fit for a new commercial district. But the Wallingford Community Council (WCC), a body with a long history of standing athwart the city’s land use debates yelling stop, has been whipping up opposition to the idea.

In an August 28 blog post, the group asked its members to request a withdrawal of Rinck’s amendment, citing a lack of engagement on the topic, but few arguments directly opposed to the idea of more housing in the neighborhood. The council has pushed to oppose Harrell’s growth plan writ large, calling out “extreme upzones” and asking its members to ask the city to “[r]etain neighborhood character and keep Seattle livable for families.” When it comes to the Gas Works Neighborhood Center, the arguments don’t appear specific to the neighborhood at all.

“The WCC is concerned that the community has not had an equitable timeline for engagement for additional Neighborhood Centers submitted with Amendment 34 compared to 30 other Neighborhood Centers identified in October, 2024 with the release of the Mayor’s Seattle One Plan,” the post read. “The request to remove Amendment 34 is justified due to the lack of equitable transparent public process and to ensure residents are not blindsided by rezones having denied Wallingford residents ten months of public engagement opportunities. Residents, particularly single-family homeowners, renters, and businesses in South Wallingford, will be significantly impacted.”

A mid-September vote to restore the Gas Works center, and any of the other seven Rinck proposes, would not immediately change zoning in the neighborhood. In early 2025, the council will start work on “phase 2” of implementing the One Seattle plan, which will entail consideration of zoning designations that will determine things like building heights, maximum density, and mixed-use zoning. But without approving an area as a Neighborhood Center, the council can’t make those zoning changes and areas next to one of the city’s most popular parks will remain exclusive.

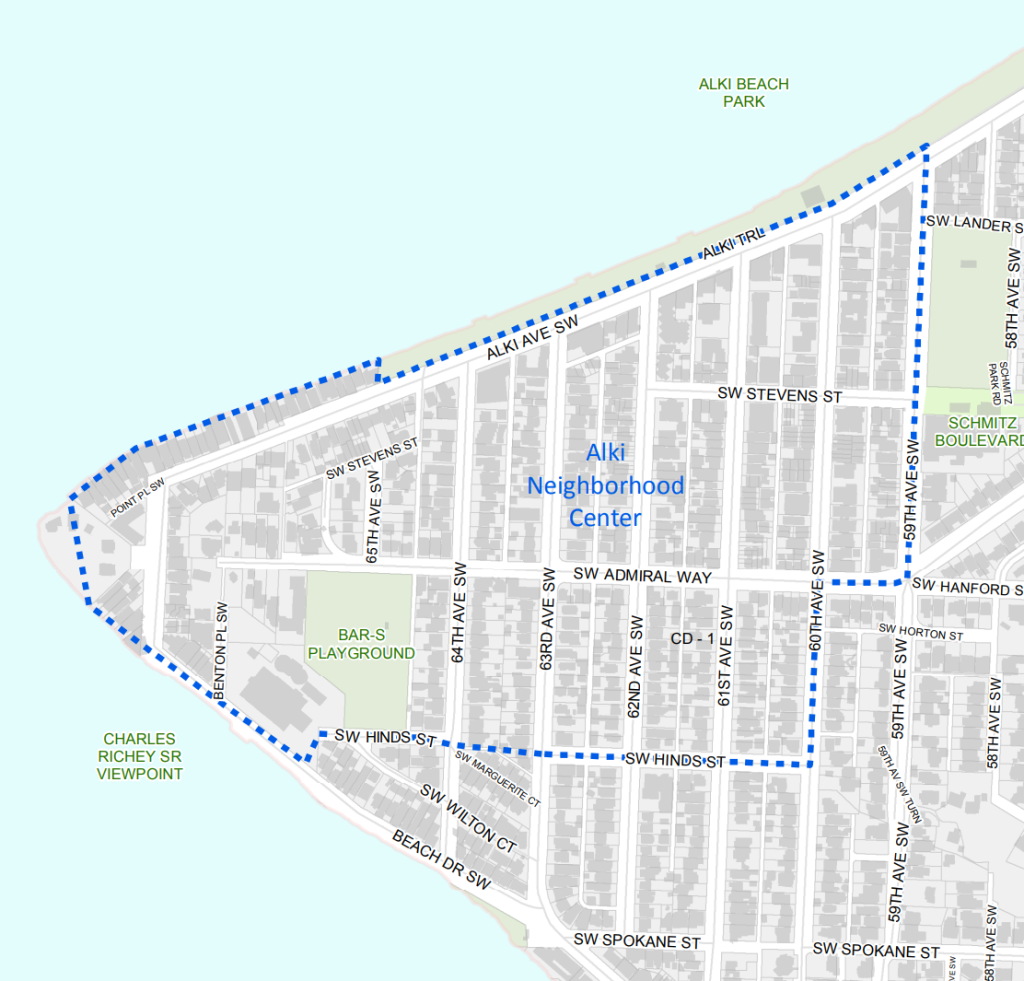

Alki

Over in West Seattle, the Alki Community Council has been pushing back on a proposal to create a neighborhood center around Alki Point, home to a bustling commercial district but few neighborhood-focused amenities. The new growth center would be directly adjacent to an elementary school that was newly rebuilt to handle an influx of students — a project that was delayed several years after a prolonged fight over off-street parking.

“95 Acres. Sweeping Changes. No Due Process,” read a September 2nd email sent to the group’s email list. “At first glance, many across Seattle understandably assume a ‘Neighborhood Center’ means a single community building for community activities. But in context of the Comp Plan and Alki, it actually means rezoning 95 acres of Alki Point into a hub of proposed stack housing and proposes to eliminate a number of building, zoning, parking and environmental regulations – with the goal of creating more housing density – faster.”

Alki community advocate Steve Pumphrey, an ally of District 1 Councilmember Rob Saka who was appointed by Saka to serve on the city’s transportation levy oversight committee earlier this year, also opposed the idea of an Alki Neighborhood Center in a widely circulated email.

“The proposed up-zoning in Councilmember Rinck’s amendment on Alki is puzzling. Many of the houses on these blocks already have ADUs and are duplexes and with changes in state statutes, they may be able to go to triplexes. Density is occurring organically in this area with existing laws and zoning codes,” Pumphrey wrote on August 21, going on to cite potential earthquakes, tsunamis, and the need for a new seawall as reasons why the neighborhood could not support additional density. And parking.

“Alki Beach is a Top Ten Urban Beach, a historic Seattle gem, and a revenue generating tourist destination. It is one of the few Seattle places where families of limited means can enjoy the outdoors and experience salt water and a tidal beach. Let’s not ruin the beach and take away that opportunity,” Pumphrey wrote.

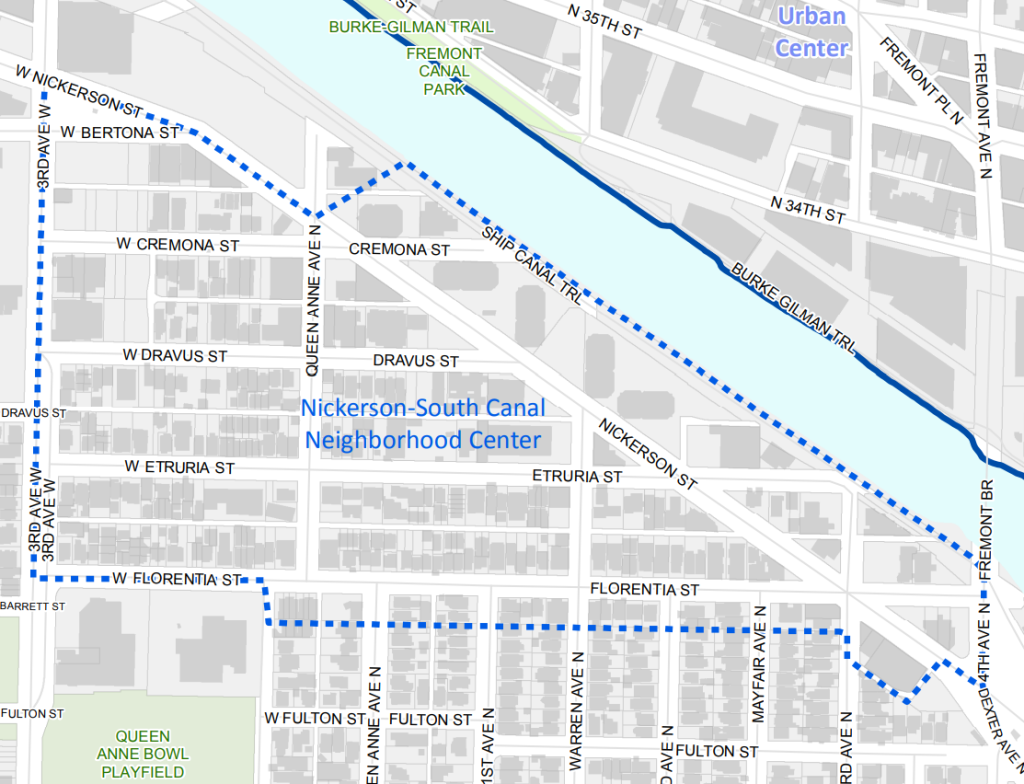

Queen Anne

In Queen Anne, the landscape is very different. The Queen Anne Community Council, which had been one of the most active groups in the city when it comes to pushing back on housing and big land use moves, has not weighed in on the city’s growth plan this cycle. That vacuum has been filled by another group, the Friends of Queen Anne, which has been focused on getting a planned expansion of the Queen Anne Urban Center, at the top of the hill, scaled back. This has led the group to support additional neighborhood centers, but in the hopes of getting reductions in areas where additional density has already been proposed.

“We recognize the need for affordable housing and are advocates of middle family housing that is built in a manner that is consistent with existing standards,” a zoning proposal from the group, dated this July, states. “[W]e believe the degree of upzoning proposed for Upper Queen Anne exceeds what’s needed to achieve affordable housing goals and poses a risk to public safety. We propose redistributing some growth from Queen Anne hill to new and expanded Neighborhood Centers on its lower slopes.”

Queen Anne’s restored Neighborhood Center would be focused around Nickerson Street between the Fremont Bridge and Seattle Pacific University. It too was proposed by Rinck, but District 7 councilmember Bob Kettle also put forward the same change in a separate amendment. While Kettle’s proposed boundaries were a little less expansive than Rinck’s, the alignment between the councilmembers suggests that a path forward is likely.

At a meeting of the Queen Anne Community Council last week, Friends of Queen Anne founder Ruth Dight told attendees that Kettle’s office had not been receptive to the idea of scaling back any changes to the Queen Anne Urban Center, even as the group has supported the Neighborhood Center at Nickerson Street.

“I want to say we’re very, very disappointed in the reception we’ve gotten from Bob. We met with him today, and we met with his staff today, and we have proposed some reductions to Upper Queen Anne, very reasonable, and he is not going to consider any of them. Bob has not considered anything that we proposed,” Dight said. “They call it a bold plan. I call it a reckless plan. It is going to wreck our neighborhoods.”

Kettle, also in attendance at the meeting, did tell the group that he doesn’t support another amendment proposed by Rinck that would expand the definition of “major transit service” to include frequent non-RapidRide buses, a move that would allow homebuilders to take advantage of density bonuses in more areas of Queen Anne and would also remove requirements to include a specific number of off-street parking spaces.

Kettle referenced his past support for Alternative 5, which was the most ambitious growth plan considered by the Harrell Administration, and included broad upzones along transit corridors. The current plan on the table only sets the stage for narrow bands of density close to transit, in a step back from Alternative 5, and yet Kettle didn’t seem ready to acknowledge that disconnect.

“We’ve been making some positive inputs to the mayor’s One Seattle Comprehensive Plan, and I think that’s to the betterment of Queen Anne and I should add — going back to being balanced and practical — again, I do support Alt[ernative 5], I do support transit-oriented development, but at the same time, we have to do this in a way, particularly balancing with neighborhood villages, you know, that we do it in a measured way,” Kettle said.

This Friday’s public hearing features virtual public comment opportunities starting at 9:30am, with in-person comment accepted at Seattle City Hall starting at 3pm. Following that hearing, the council will vote on the proposed amendments on September 17, 18, and 19.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.