Ballard Link’s cost nearly doubled, surpassing $20 billion in new agency estimates.

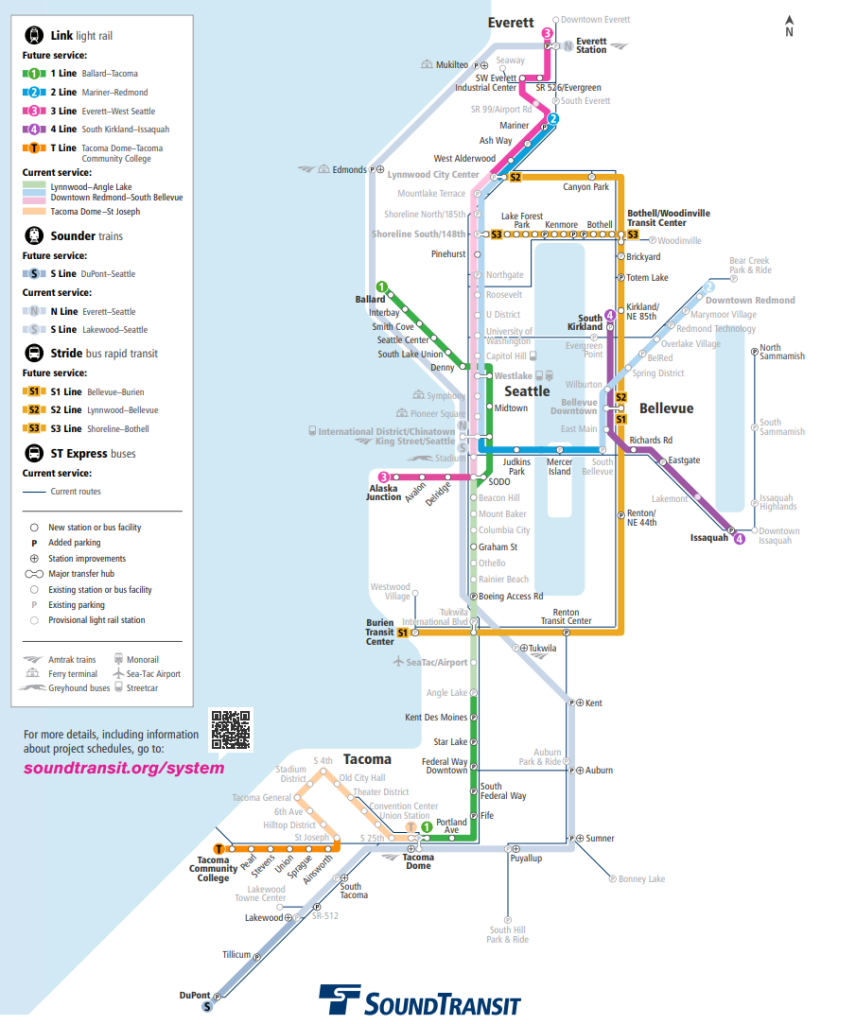

Sound Transit planners presented the results of months of deep diving into ways to reduce costs on two major light rail extensions last week, with some good news and some bad news. As costs continue to creep up on projects across the board, finally connecting the light rail “spine” into Everett still looks affordable for Sound Transit, with some strategic moves. But Seattle’s short light rail line between SoDo and West Seattle remains well above initial cost estimates, despite significant value engineering work.

The presentation was the first comprehensive look at the work Sound Transit’s capital team has been doing to bring costs down since the announcement that the agency’s constellation of system expansion projects around the region faces a $20-$30 billion gap through 2046. That shortfall is on top of another $10 billion needed expenses to maintain reliable operations and projected decreases in revenue. That capital work, led by Deputy CEO Terri Mestas, includes scouring projects already in planning for ways to deliver them more cheaply.

Without bringing costs down, the region is heading toward a showdown at the Sound Transit Board of Directors. Elected leaders in Piece and Snohomish Counties have long been pushing to complete the “spine” of the light rail network between Tacoma and Everett, and some have admitted they would delay Seattle projects to do it. Meanwhile, Seattle’s board contingent is pushing to advance the next two in-city lines to Ballard and West Seattle.

But all projects are not created equal, with the urban lines facing much bigger cost pressures due to more complicated alignments and steeper land costs in the densely built core of Seattle. So unless the capital team is able to pull a rabbit out of a hat, a clash over slashing Sound Transit 3 (ST3) projects may be inevitable.

On top of a new $7.9 billion high-end cost estimate for West Seattle Link and a $7.7 billion one for Everett Link, Sound Transit released new cost estimates for all of the ST3 projects still in the pipeline, including a brand new, eye-popping $22.6 billion high-end estimate for Ballard Link.

We now have the project-level breakdowns for Sound Transit 3 light rail projects, outlining the $20-$30 billion shortfall the agency is facing through 2046. Ballard Link's 2025 $ estimate is now $22.6 billion, a full 90% increase. The Boeing Access Road infill station is now at $475 million.

— Ryan Packer (@typewriteralley.bsky.social) September 15, 2025 at 2:00 PM

[image or embed]

While Ballard Link’s cost estimate has nearly doubled from the previous $11.9 billion estimate, abandoning the project could have huge repercussions felt not just in Seattle. Ballard Link is projected to attract the most ridership by far, while providing a second light rail tunnel in downtown Seattle that would grant the entire system more service reliability and capacity, giving riders regionwide higher frequencies.

Along with inflation impacts on both materials and soft costs like engineering, the new cost estimates are the result of updated methodology that essentially took a fresh look at each project from a “bottom-up” perspective, rather than a higher level one. In other words, the initial cost estimates for all of these megaprojects were somewhat illusory.

“Based on our experience from the updated cost estimates on the West Seattle Link Extension, the other light rail project teams employed a modified bottom-up cost estimating approach (appropriate to each project’s level of design) to better account for project-specific construction challenges and construction cost inflation,” Mestas wrote in a memo dated last week detailing the bad news to CEO Dow Constantine. “These cost drivers are not felt consistently across the capital program. Projects with more complexity in their scope are subject to higher potential cost growth. This complexity includes elements like water crossings and tunneled segments where additional design detail based on current market conditions give us an improved understanding of potential cost.”

Board members also got a clear look Thursday at phased opening scenarios for some of these projects, by building what’s called the “minimum operable segment” and leaving the rest of the line to be built later. While that would put both Everett and West Seattle into the affordable range, choosing that last-ditch option would likely please no one, and create more costs down the line if a future Sound Transit 4 project were to be approved to complete the job.

Right now, the board is nowhere near considering these worst-case scenarios.

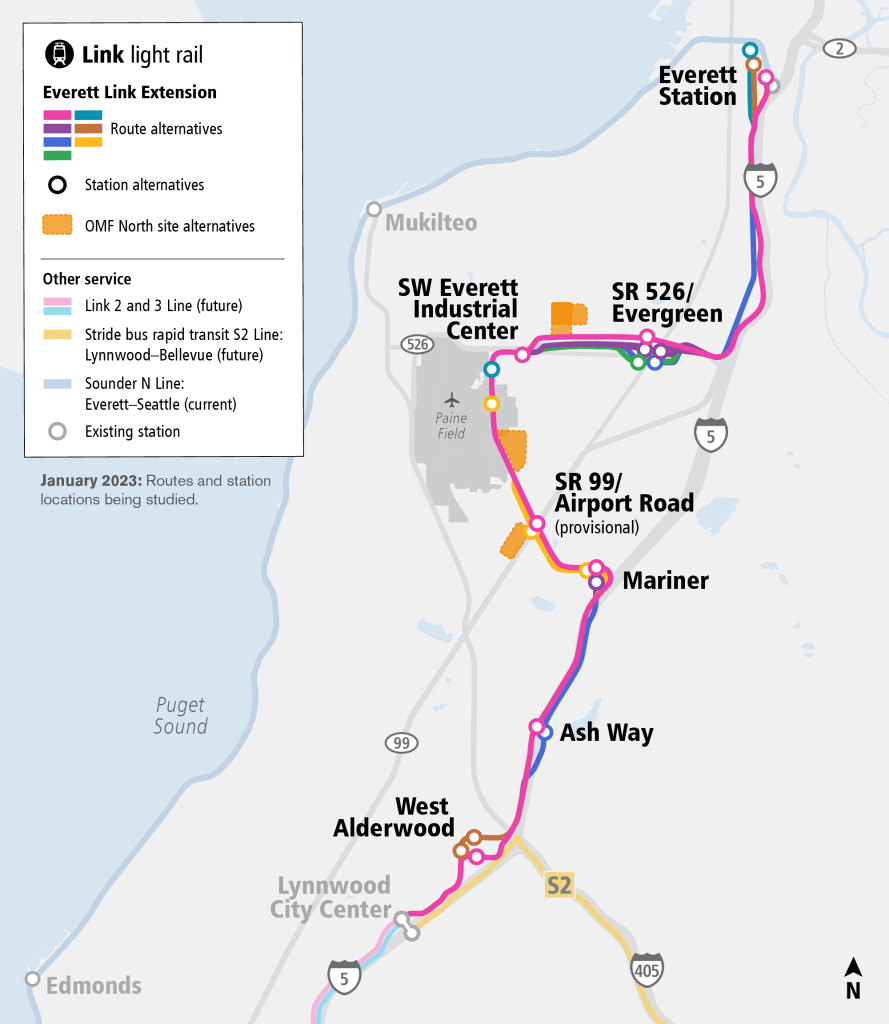

Everett Link could run more at grade, avoid more private property

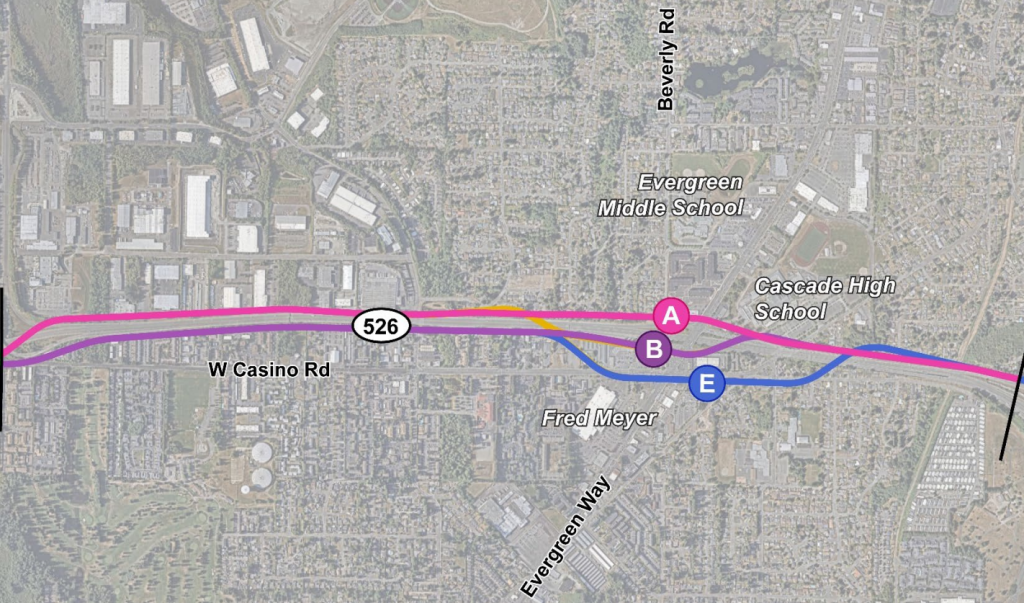

Thursday’s presentation showed just how optimistic Sound Transit’s capital delivery team is when it comes to getting Everett Link into a more affordable cost range, with a series of changes that probably should have been part of the design all along. The most significant adjustment would be a change to the light rail guideway’s alignment on Evergreen Way to utilize more highway right-of-way, avoiding building demolitions.

The Urbanist has been raising the alarm about both the cost and community impact about the options on the table for Everett Link since 2023, when the agency posted initial concepts showing the need to acquire large swaths of property, displacing numerous businesses in the process. While that appears to remain the plan for many areas along the route, Sound Transit is reconsidering it along Evergreen Way where the light rail guideway can likely be better accommodated along the state highway right-of-way. That could save Sound Transit as much as $100 million dollars.

Sound Transit also thinks it can save up to $85 million around Lynnwood’s Alderwood Mall, by eliminating a wide “pocket track” near what will be Lynnwood’s second light rail station. A pocket track is a stretch of rail separate from the main line where trains can be stored temporarily, either in the case of service disruptions or to provide additional service for special events. But eliminating the pocket track here, Sound Transit can avoid having to acquire properties belonging to 24 different businesses.

Sound Transit also expects to be able to save $80 million by running a section of guideway near Paine Field at-grade for an additional 4,000 feet. That section wouldn’t include any additional at-grade crossings, and the height of the track would lead to the elimination of the mezzanine at the SW Everett Industrial Center station, which is included in those cost savings.

Combined together, Sound Transit presented options that get Everett Link to $6.4 billion, a 13-16% reduction that puts the project back into the affordable range of its financing plan. The agency still has more work to do to refine these options and confirm the full potential of what was surfaced last week. But it looks like a path forward exists for Everett Link without requiring the jettisoning of stations.

West Seattle Link and the tough path forward

Getting West Seattle Link down to an affordable level looks to be an order of magnitude more challenging than Everett Link. With a new total cost estimate of $7.1 to $7.9 billion for four stations, getting to West Seattle now looks to be even more expensive than getting to Everett, despite being a line that would be 75% shorter and include two fewer stations. Crossing the Duwamish Waterway, building a tunnel to Alaska Junction, and working in an urban corridor where land is at a premium are all contributing to greater costs — and setting up a likely clash between Seattle’s board continent and other members.

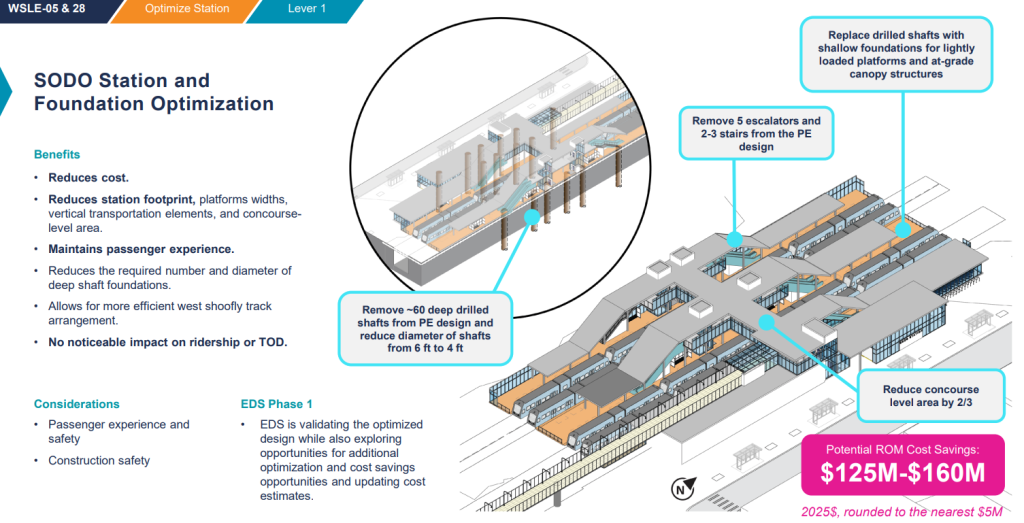

Sound Transit has found some very promising areas for cost savings, even if they likely won’t be enough to get the project in the affordable range. Redesigning West Seattle Link’s SoDo station, by removing five escalators and two or three sets of stairs and shrinking the concourse level by two-thirds, could save as many as $160 million dollars — a fact that begs the question as to why it was planned like that in the first place. (The Urbanist has repeatedly highlighted the oversized station issue, most recently in a June deep dive.)

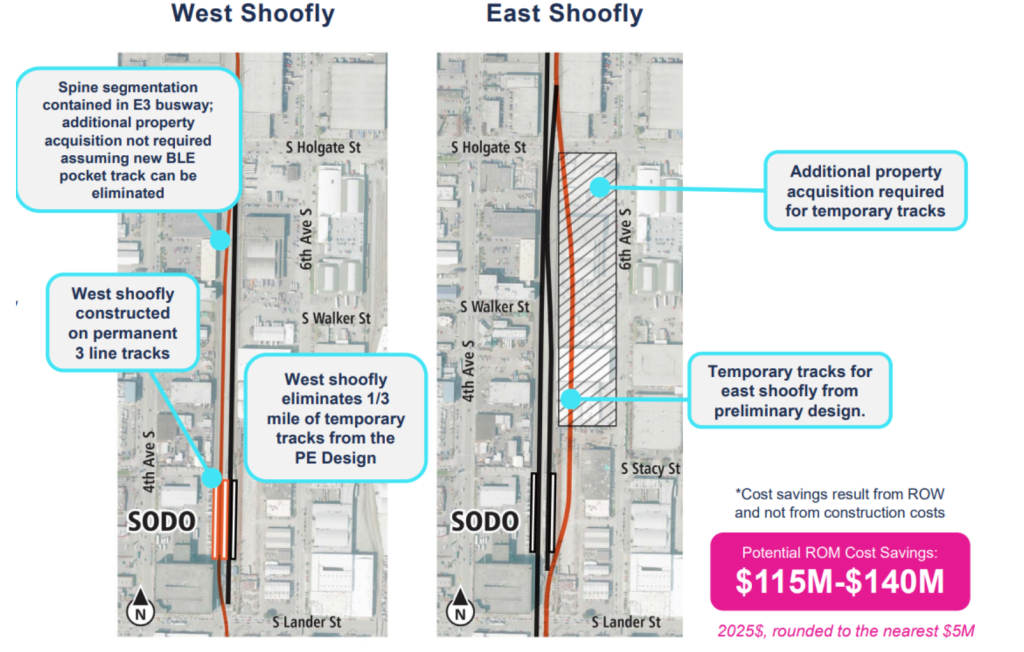

Another $140 million can potentially be saved by shelving plans for a third-mile stretch of temporary (or “shoofly”) tracks in SoDo, avoiding the need to demolish several blocks of buildings along the existing light rail guideway. By moving the shoofly to the west, Sound Transit can run 1 Line trains through the construction zone on the future 3 Line, which will ultimately run from West Seattle to Everett.

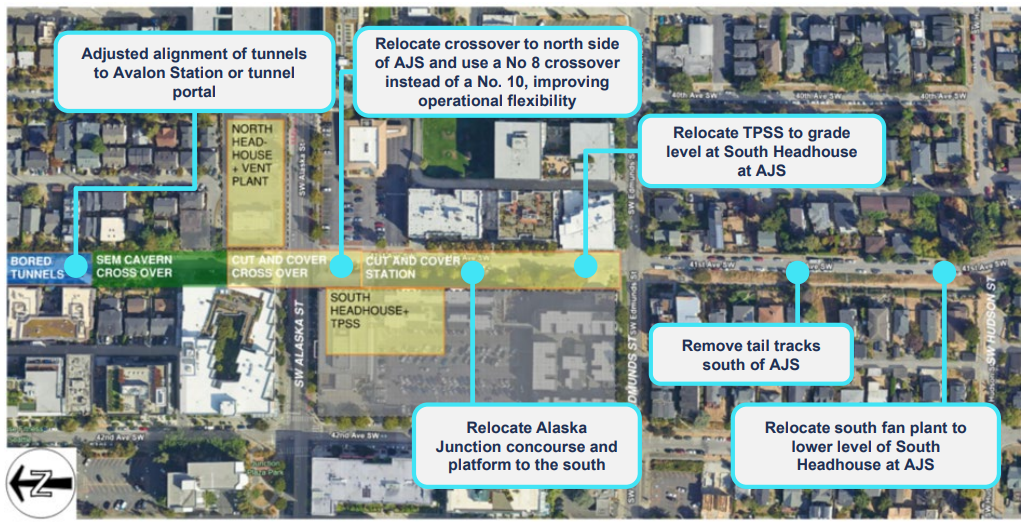

Another item in the “why weren’t we doing this before” category are some changes to West Seattle Link’s terminus at Alaska Junction, removing tail tracks south of the station and relocating the station concourse and platform. Avoiding the need to demolish “basically a full block” of the Junction neighborhood, Sound Transit would also gain operational efficiency in a way that could save around 3 minutes per trip in terminal processing time. And the dollar figure saved could be as much as $235 million dollars.

Sound Transit also expects to save up to $160 million in costs on West Seattle Link by using precast guideway segments that are then brought on site for construction, reducing environmental impacts at the same time as they bring down costs.

Without dropping any of West Seattle Link’s stations, Sound Transit only presented options that get the line’s costs down by 8-11%, or just under $7 billion dollars total. While not insignificant, the project remains unaffordable to the existing financing plan as designed — and provides a preview of many of the same issues that are likely to come up on Ballard Link, but on an even bigger scale.

The tough case to retain Avalon Station

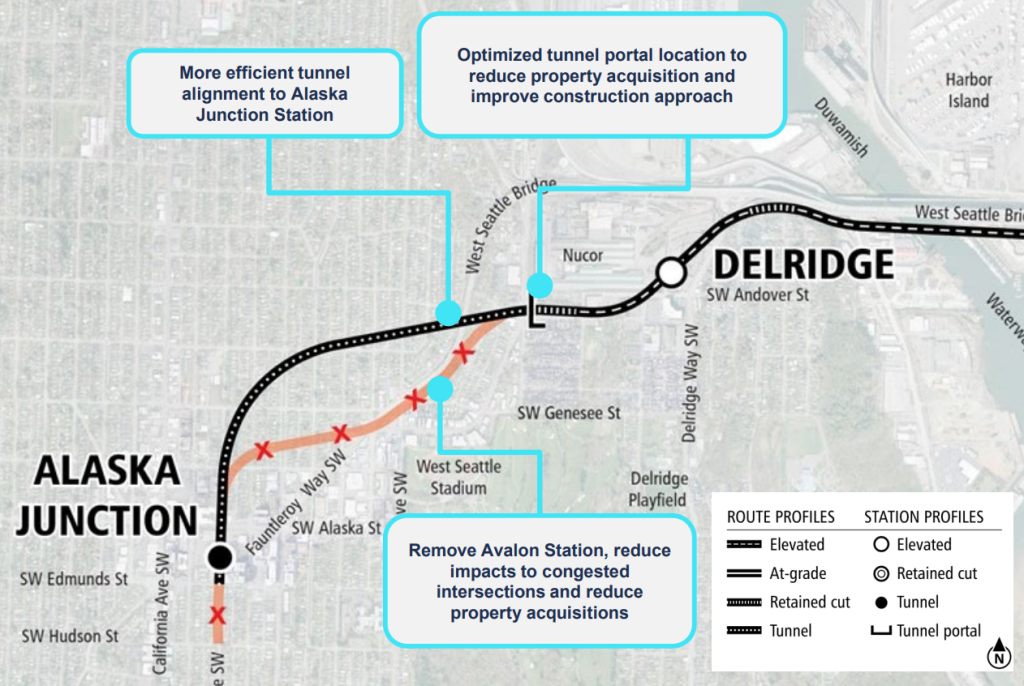

Short of West Seattle Link’s minimum operable segment, which would terminate at Delridge Way, the board also looked at the impact of cutting the line’s station at Avalon Way. Midway between the Delridge and Alaska Junction stations, Sound Transit’s ridership models continue to show negligible impact from dropping this station, assuming riders will simply end up at one of the other neighboring stations.

Those blunt ridership models likely have their faults, but Seattle board members are going to have a tough time making the case for retaining Avalon in the face of so many other cost pressures.

Without an Avalon Station, Sound Transit would be able to better position the start of the tunnel to Alaska Junction to avoid property impacts, and improve the alignment of that tunnel itself, saving up to $470 million dollars. Potential removal of Avalon Station was contemplated in West Seattle Link’s environmental review already, so the pathway is there even after the federal approval for the project was issued earlier this year.

Neither of Seattle’s two representatives on the board were quite leaping to Avalon Station’s defense. Dan Strauss, who represents Northeast Seattle and Magnolia, took a diplomatic route after reemphasizing his support for completing the light rail spine.

“I need to know much more information about all of these cost saving measures, as well as the context for the region before I think that removing the Avalon Station is a good idea,” Strauss said. “There’s a lot of important reasons why we had Avalon on the original plan, and [I’m] just saying, because we’re moving the tunnel portal, that’s not a good enough reason.”

Strauss’s council colleague, Rob Saka, the transportation committee chair but not a Sound Transit board member, had been much more full-throated when it came to Avalon Station during a council meeting earlier in the month.

“Don’t pare those back,” Saka said during a discussion on city staffing increases needed to handle ST3 permitting. “Don’t cut corners to pare those back. Look at those other things, engineering efficiencies, this is to the Sound Transit board: we need all three of those stops, every last one. Don’t pare those back, find other ways to address the need. If you only have three of something and you take one away, it completely guts the value proposition of the original thing. We want more people to take transit. Taking one of three away is not going to get it done.”

But with Seattle’s ST3 lines set to bear the brunt of cost increases due to their unique design elements, city leaders are likely going to become dealmakers trying to find any path to getting projects through to construction. After all, two stations would be better than no stations.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.