King County Metro’s 2035 goal to fully zero-emission transit fleet would be delayed more than five years under the proposed two-year budget Interim King County Executive Shannon Braddock released Tuesday. With agency resources spend thin and bus electrification technology unlikely to be able to handle the job of getting Metro emissions free by 2035, the goal the county established five years ago, Metro will pivot resources back toward delivering transit service.

Delaying electrification investments would push off the agency’s fiscal cliff, which had been looming before the end of the decade under a more aggressive electrification timeline.

Following the planned opening of Metro’s first all-electric bus base in Tukwila early next year, Metro had been planning to move onto other base overhauls, including a $448 million upgrade to nearby South Base Annex that would have increased charging capacity from 120 coaches to nearly 400. On that project’s heels was set to be a $176 million overhaul of SoDo’s Central Base, a project that would have resulted in significant rerouting for deadheading coaches at around the same time that Sound Transit was set to start construction on West Seattle Link close by.

Last year, a report from King County’s auditor noted significant risks that could come from moving ahead with South Base Annex, including a lack of contingency funds, geological issues, and permitting delays. “Delays in development of the South Annex Base may mean that Metro Transit will not have sufficient infrastructure to support its planned fleet of 337 battery-electric buses in fall of 2028, which could lead to service disruptions,” the report noted at the time.

Following that audit, King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci had requested a report on potential trade-offs between electrification work and service, work that likely played a big role in informing this year’s budget proposal. That report is set to be released in the coming days.

With this proposal, Metro now doesn’t expect to fully decarbonize its operations until the mid-2040s, and will draw out its ambitious schedule for major bus base overhauls in favor of slower retrofitting, along with additional small-scale projects like the expansion of the existing trolleybus fleet. Metro’s trolleybuses have long provided zero-emission service, but Metro’s electrification plans have not leaned heavily on them.

Rather than going all-in on battery electric buses (BEBs), Metro will continue with a more diversified set of bus purchases, acquiring BEBs but also the more reliable hybrid diesel-electric buses that can be depended on to deliver service on Metro’s workhorse routes. In December, The Urbanist noted such an electrification strategy reset may be coming due to mounting obstacles.

“Our new approach is to go incrementally, to retrofit the base according to what the technology can provide from a service perspective. And so both that helps with cost and it also preserves continuity of service for the riders,” Metro General Manager Michelle Allison told The Urbanist. “Before, we had assumed you would shut down a whole base, move that service elsewhere and bring it online.”

A full recalibration of Metro’s electrification program is a stark illustration of the trade-offs transit agencies across the country face in managing ambitious climate reduction targets in the face of rising labor and project costs, limited U.S. electric coach manufacturers, and increased federal uncertainty around transit funding.

Despite the fact that Metro has been experimenting with all-electric coaches for nearly a decade, the existing fleet remains small. Not all trial runs have gone well. Metro’s retired its first set of Proterra battery buses after just a few short years of service, following that company’s bankruptcy two years ago.

“We’re continuing to keep focused on trying to make sure we have a really good, sustainable service. But for now, it doesn’t make sense to keep pushing on that date when we just know, realistically, we need technology to catch up and supply to catch up,” Braddock told The Urbanist following her budget speech.

While pivoting away from electrification work, Metro plans to continue ramping up service over the course of this budget cycle, restoring 334,000 annual service hours that had been suspended during the Covid-19 pandemic. That’s on top of additional service hours planned for the county’s next two RapidRide lines, the I Line between Renton and Auburn and the J Line between Downtown Seattle and the University District. Those 334,000 hours are more than had originally been planned, with fewer service hours now needed to account for reroutes during base electrification work.

“We know there’s this balance between new technology and service, and what we really want to do is create a zero-emissions program that’s service driven,” Allison said. “Being able to invest those service hours and get those hours out on the street, knowing that the technology is going to lag a little bit [more] than what we assumed, is where we are now. With the new program, we’re not going to do 100% base conversions all at once. We’re going to do it incrementally as technology lags, so it can be service preserving as well.”

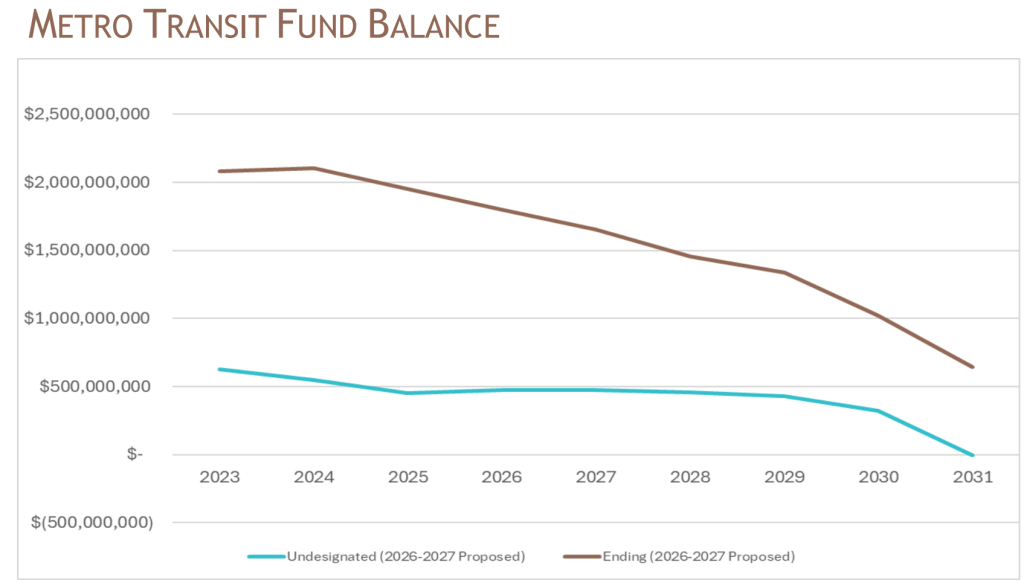

The revision in Metro’s plans doesn’t mean a fiscal cliff is fully eliminated, just pushed out by a few years, as the agency is able to hold onto more of its fiscal reserves even as costs outpace the revenues coming in. For a true fix, additional funding is going to be needed to match the planned pace of service expansion that is ultimately the bare minimum needed to sustain a growing region.

“Metro’s current revenue sources are inadequate to fund the current level of operations and an ambitious capital proposal in the longer run,” the Executive’s budget book notes. “By 2031 Metro will exhaust its undesignated fund balance and will either have to reduce spending or start to use reserves set aside under current policies.”

King County is currently not utilizing any of the 0.3% sales tax authority available to fund transportation, via the King County Transportation District. With Seattle’s counterpart sales tax measure set to come up for renewal in late 2026, many transit advocates had been pushing to take the city-controlled measure countywide, but all signs point to that opportunity not coming together, with the King County Council instead only considering a 0.05% sales tax for Metro that could be approved by a council vote.

With cities around the county also approving 0.1% sales tax measures to fund public safety investments thanks to a new change in state law, sales tax fatigue is likely to contribute to pressure against expanding use of the transportation district.

The King County Council had been weighing a countywide transit measure in 2020, but the Covid pandemic led them to shelve plans. In the intervening years, a labor shortage among bus operators and mechanics (also tied to the pandemic) complicated plans to expand service. Nonetheless, Seattle’s overwhelming success passing its bus funding measure in 2020 suggests an electoral path for a countywide measure.

For now, Metro’s change in approach on electrification work will turn down the financial pressure and allow Washington’s largest transit agency to focus on its core mission: providing transit service.