Open a path through the fence to improve access to the Union Bay Natural Area.

The Union Bay Natural Area (UBNA) is 74 acres of public open space with miles of trails and shoreline habitat. Located between the University of Washington light rail station and U Village, it’s a breathtaking natural environment, owned by the State of Washington but managed by the University of Washington (UW).

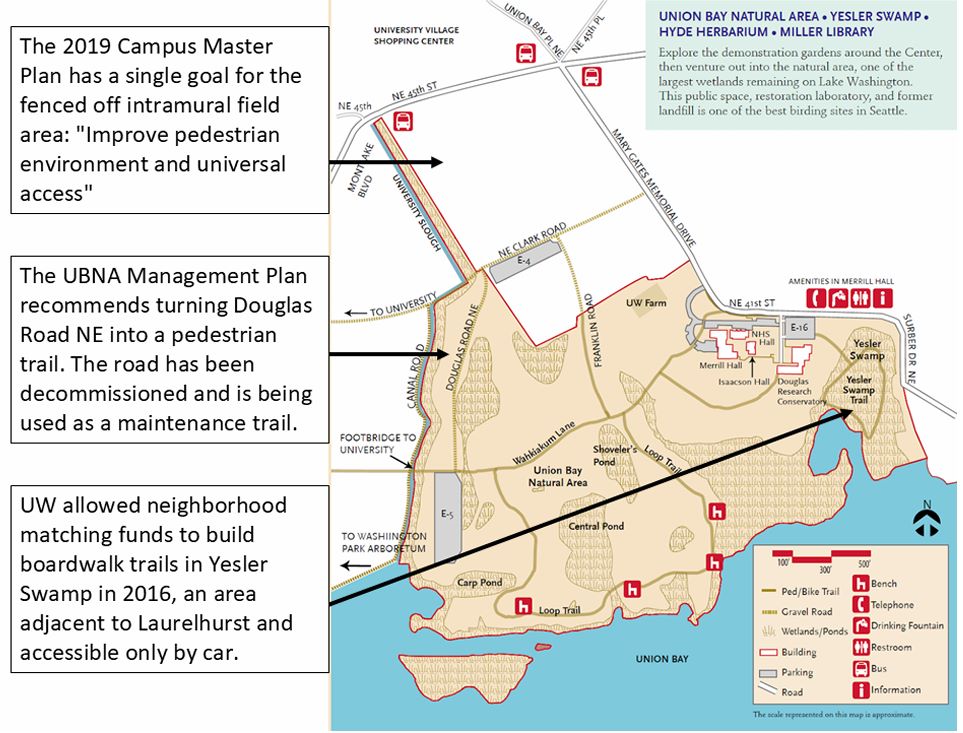

The University says all the right things about the natural area. The UBNA management plan calls for an “overarching goal” to “increase the area’s service to the public,” noting that “an expansion of the trail system would increase the site’s value and its utilization by the public.” The Campus Master Plan sets one goal for the adjacent intramural field area: “Improve pedestrian environment and universal access.” UW’s sustainability plan and active transportation goals also point toward opening UBNA to the public.

On paper, it’s an inspiring vision: a vast area of wetlands and trails serving students, families, commuters, and wildlife. Too bad it’s fiction.

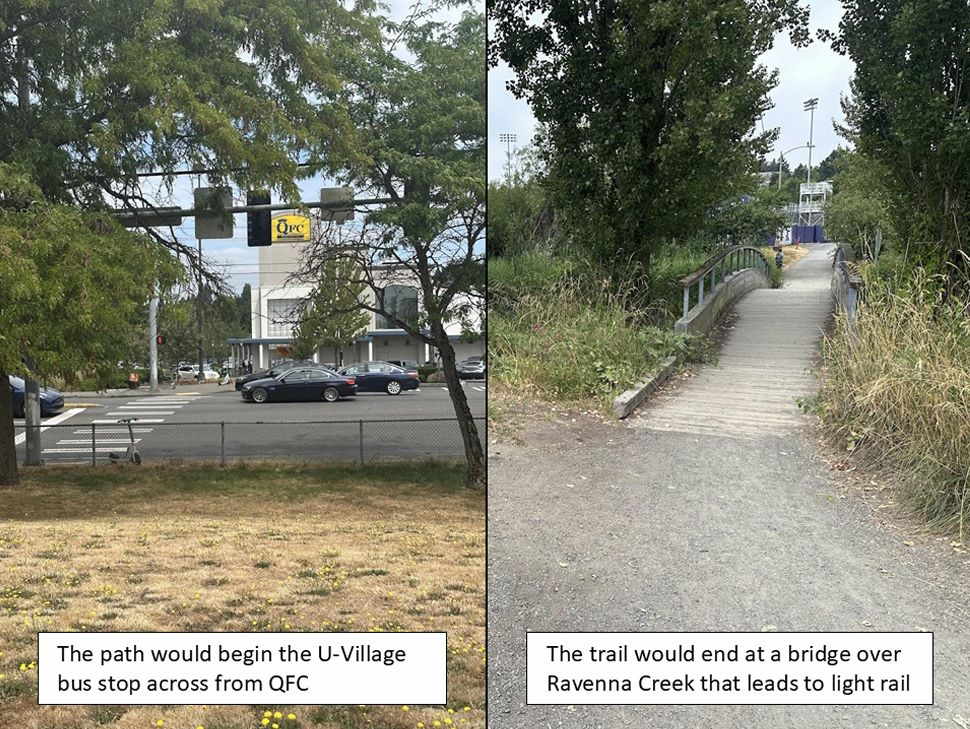

Instead of welcoming people, UW walls the public out. From the U Village bus stop, you don’t find inviting trails — you find a mile-long, unbroken fence. Try walking around it, and you’re pushed against five- and seven-lane roads ending at giant parking lots marked “NO PEDESTRIAN OR CYCLIST ACCESS.”

In other words, bring a car, or stay out.

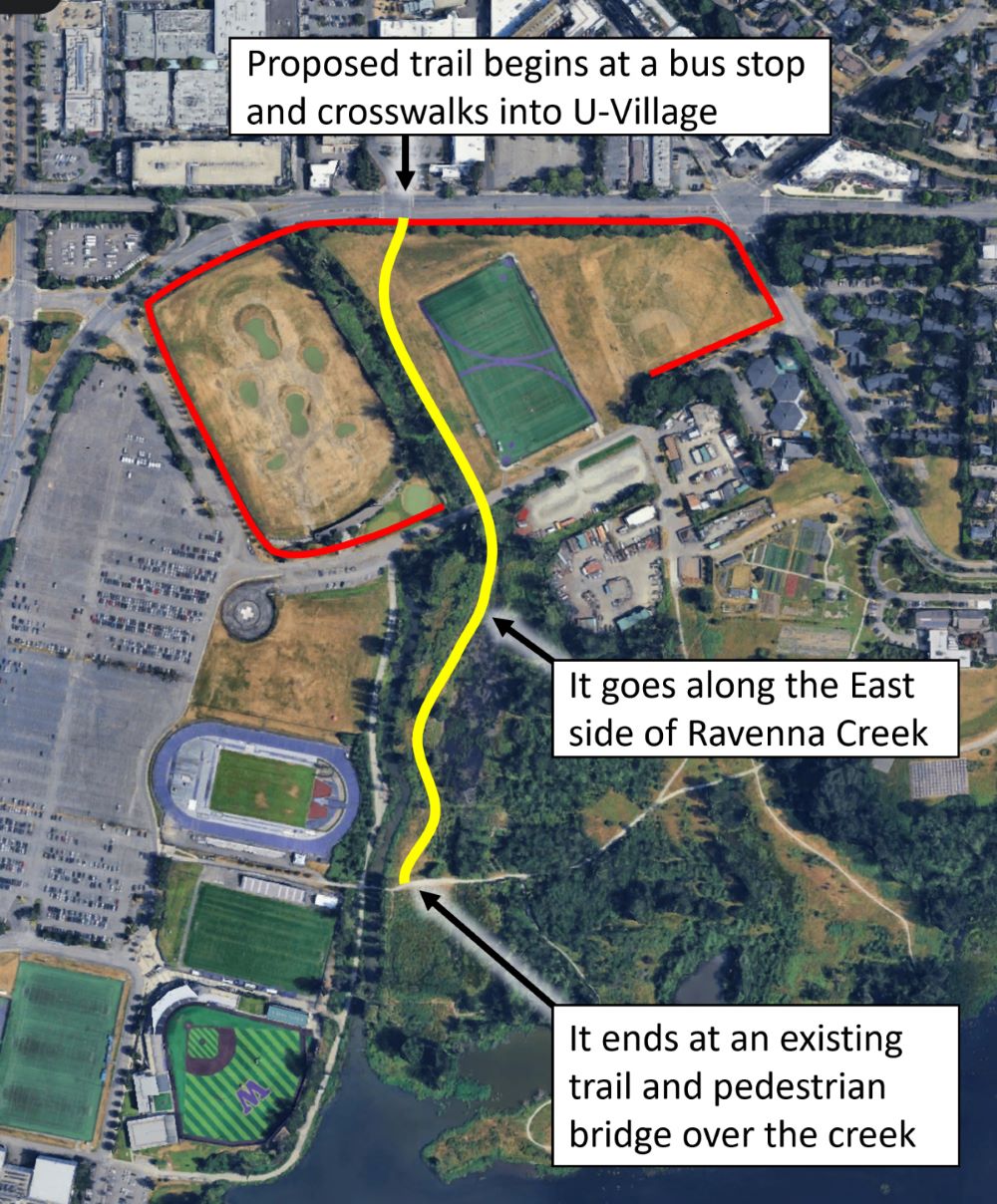

Community groups proposed a modest, no-cost solution: open a gate at the bus stop across from the U Village QFC and build a trail along Ravenna Creek, ending at an existing pedestrian bridge. The path is not only aligned with UW guiding documents, but the UBNA Management Plan specifically recommends building a public trail on decommissioned Douglas Road, which is where most of this trail would go. The end result would be both beautiful and practical — ideal for commuters and recreation.

The Center for Urban Horticulture and UW Farm, both in UBNA, have missions rooted in sustainability and public engagement. Robert Swan, a UW School of Environmental and Forest Sciences Instructor, noted the opportunities the trail would bring for students.

“UW students are some of the most active, passionate, and hard working volunteers out there,” Swan said. “This pathway provides a rare chance to benefit everyone and everything involved – improving equitable access, creating green spaces for people and wildlife, and allowing UW students to improve their community while helping build it all.”

To gauge public support, the project was featured at the U District Street Fair, where it was a top choice with 758 public votes. To get things on track we proposed that the trail could be built without UW funds. We could model the project on the UBNA Yesler Swamp boardwalk project that was completed in 2016. Built with community funds, the project is an elevated set of boardwalks that are adjacent to Laurelhurst, in a location only accessible by car.

After the street fair, U District Advocates met with UW representatives to request permission to design the trail. Unlike the Yesler Swamp boardwalk project, this project would be a simpler wood chip trail and would be accessible to the active commuters and public transit users that UW guiding documents claim to support. It all seemed like a no-brainer — let a neighborhood group pay so UW can achieve the specific vision they’ve laid out in their own guiding documents.

UW’s response? No.

Their facilities department said the fence’s purpose is to keep people out. They said the quiet part out loud: they don’t want more pedestrians, transit riders, or cyclists in UBNA. They want the area prioritized for maintenance trucks, with parking lots as buffers that keep out the homeless and transit users. Forget equity. Forget sustainability. Forget the state law requiring UW to manage UBNA for recreation, habitat, and education.

This isn’t just hypocrisy — it’s a power play. The UBNA is supposed to serve the public. Instead, UW treats it like its own fenced backyard, a dumping ground for trucks and gear. When the community offers a project that costs UW nothing and fulfills their own promises, they slam the door.

Meanwhile, faculty and students who value public engagement are baffled. The UW Farm, the Center for Urban Horticulture, and instructors who teach sustainability all want this trail. They see it as hands-on work that benefits both students and the community. But the facilities bureaucracy’s priority is keeping the public out of public land.

Here’s the bottom line: Union Bay doesn’t belong to UW. It belongs to the people of Washington. State law recognizes it as a wildlife habitat and mandates it be managed for education, habitat, and recreation. UW’s “access” through the Center for Urban Horticulture in Laurelhurst doesn’t meet that mandate, nor their own commitments to sustainability and accessibility.

If UW won’t honor its promises, the state can step in — tying future funding to the trail’s approval, or even transferring UBNA to Seattle or King County Parks, where public land is managed for the public.

This is a rare chance to get it right: a low-cost, high-impact win for equity, sustainability, and public health. UW’s leaders need to treat their guiding documents as more than rhetoric.

For now, we’re asking for something simple: let us walk through the gate.

To take action and support this proposal, visit the Union Bay Nature Trail website.