Beacon Hill residents along 21st Avenue S have been waiting a long time for sidewalks.

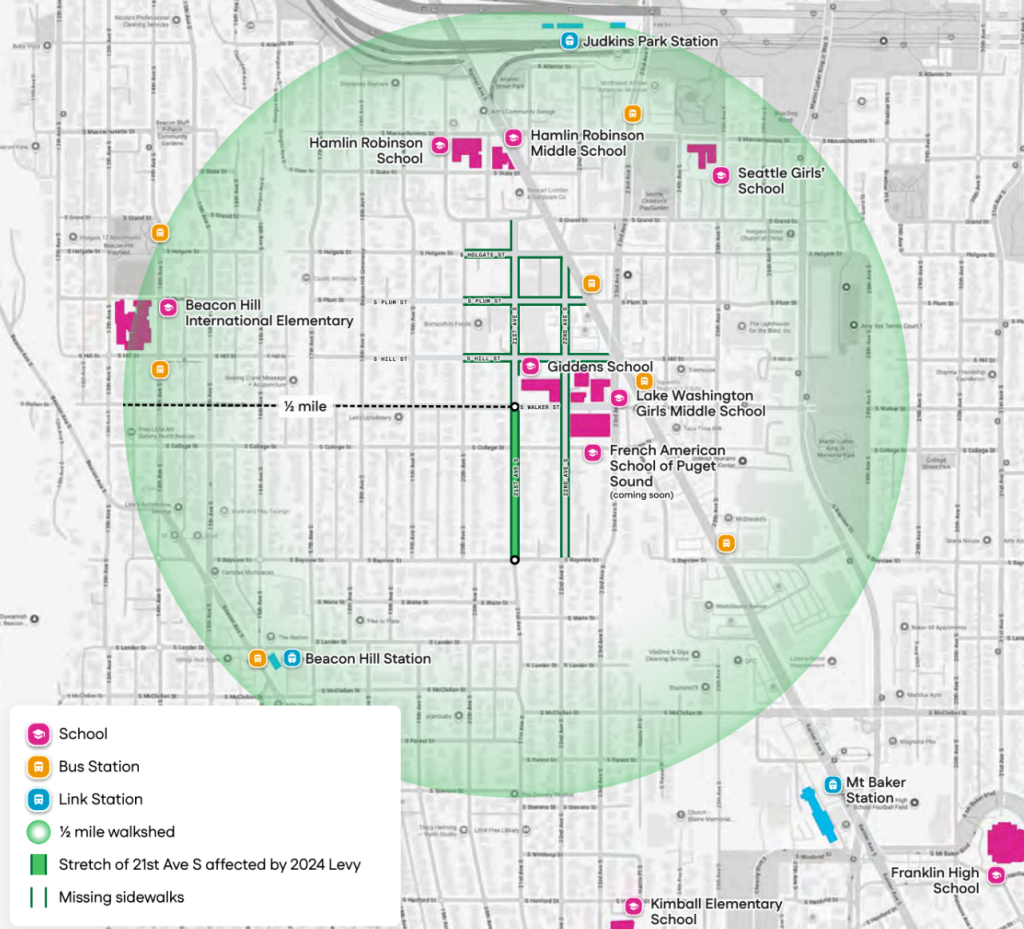

Situated about halfway between Seattle’s Beacon Hill and Mount Baker light rail stations, 21st Avenue is close to several schools and can become a major thoroughfare close to school pick-up and drop-off times. Given the roadway’s slope, the street often floods when stormwater accumulates from further up the hill, and many homeowners along 21st have taken measures to protect their homes from flooding, including building rock walls and adding asphalt berms.

South of Bayview Street, sidewalks have been in place along 21st since the late 1960s, but north all the way to Rainier Avenue, longtime residents have spent decades walking without sidewalks or benefitting from proper curbs and drainage. The newly built Giddens School, which moved to Beacon Hill from the Central District in 2019, was required to add sidewalks in front of the school, but they sit disconnected from the broader sidewalk network.

Four blocks north of the Giddens School is the recently completed Grand Street Commons, a mixed-income apartment complex that added 569 homes to the neighborhood when it was completed in 2024. The builder added new sidewalks on the immediate blocks, but the City has not connected them to the nearby elementary school.

21st Avenue is just the type of area that Seattle’s 2024 transportation levy was intended to benefit, with voters approving a record amount of funding to build new sidewalks. On top of $111 million dedicated to expand the city’s sidewalk network, the $1.55 billion levy also includes millions more for sidewalks as part of neighborhood traffic safety projects.

However, since Seattle is missing sidewalks on around 11,000 of the blocks citywide — around a quarter of all blocks — the plan for 21st Avenue S comes with a catch.

Rather than a full curb-and-gutter sidewalk, built using concrete, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) plans to install an asphalt pathway along the west side of 21st, separated from the street by precast concrete wheel stops. This is the type of sidewalk typically seen in commercial parking lots. The project was included in the first tranche of sidewalk projects included in SDOT’s 2025 levy delivery plan, along with around 20 other projects set to start construction by the end of this year.

To Dana Lee, who moved to 21st Avenue with her husband Dan in 2019, that plan doesn’t fulfill the implicit promise that the city made when it started installing sidewalks in the neighborhood 50 years ago. She has been advocating for a full sidewalk, after initially spending years just trying to get the issue of building sidewalks on 21st onto the city’s radar.

As a non-arterial, or neighborhood street, 21st Avenue is far from alone in being slated for a more quick-build treatment for new sidewalks. An innovation developed during the previous transportation levy, 2015’s Levy to Move Seattle, SDOT has built dozens of lower-cost “pathways” or “sidewalk alternatives” over the past decade in the hopes of making bigger inroads in bridging gasps in the sidewalk network. For the most part, new concrete sidewalks have been reserved for arterial streets, the busiest corridors in the city where transit routes and businesses are concentrated.

But Lee sees the plan for an asphalt pathway as shortchanging the neighborhood, continuing a pattern of disinvestment. She points to other low-cost pathways that were installed throughout South Seattle during the Levy to Move Seattle era that have started to deteriorate after less than a decade of use. Elsewhere in Beacon Hill, along a stretch of S Kenyon Street near Beacon Avenue, the wheel stops have started to be swallowed up by weeds, and vegetation growth has narrowed the effective width of the sidewalk, potentially falling short of Americans with Disabilities Act [ADA] standards.

“The city keeps reiterating that the asphalt walkway will be ADA compliant, but research has shown that asphalt has crumbled over time. It doesn’t last for more than 15 years, and it’s just another example of the burden of funding being placed onto the community,” Lee told The Urbanist. “This community has waited for 60 years to get a true concrete sidewalk. And I think we’re willing to wait a little bit more time to get you know what we expect, which is, you know, a true safe walking path for the kids and the elders who have been here since the 60s to walk on and enjoy.”

SDOT told The Urbanist that advancing the quicker-built design option here was actually a reflection of the city’s prioritization of the gap along 21st. A permanent sidewalk, on the other hand, could cost the city as much as $6 million dollars — around half of the city’s annual budget for new sidewalks funded by the new transportation levy. In part, that high estimate is driven by the factors along the street that are pushing many residents to ask for this infrastructure, namely a need to manage drainage in a better way. The permanent sidewalk would also likely include street trees — adding to South Seattle’s tree canopy.

“This non-arterial street was prioritized for a walkway among the 11,000 missing blocks in Seattle because it is a gap in the pedestrian network connecting to two schools, frequent transit on Rainier Ave S, and the new Judkins Park light rail station,” SDOT spokesperson Mariam Ali said. “We are proceeding with a quick-build design walkway on the west side of the street that includes concrete curb ramps, driveways, and curbs, and an asphalt walkway. We expect to have 90% design to share as soon as January.”

SDOT didn’t conduct any direct surveys on its plan for an asphalt path along 21st, so Lee took measures into her own hands, collecting responses from over 50 of her neighbors. The results were striking: 88.7% of the respondents said they either feel “unsafe” or “very unsafe” walking along their street, with the same number of respondents saying they’d like to see a sidewalk on both sides of 21st to improve the situation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, no one supported the idea of an asphalt path when presented with the option of a full sidewalk.

The results of Lee’s outreach clearly show a broader desire from residents for a solution that is seen as more permanent.

“Installing two concrete sidewalks instead of a single asphalt one is a safer, longer-lasting, and more equitable choice for the neighborhood. Having sidewalks on both sides of the street protects pedestrians — especially children, seniors, and people with disabilities — from having to cross unnecessarily, reducing the risk of accidents,” one 21st Ave resident wrote in Lee’s survey. “Concrete also provides a sturdier and more accessible walking surface that stays cooler and resists cracking and tripping hazards better than asphalt.”

“Our neighborhood is structured around transit. We cannot all drive — make it easy for everyone to use our feet,” another respondent wrote.

From the City of Seattle’s perspective, turning to lower-cost solutions is the only way that the pace of filling in gaps in the sidewalk network will be able to quicken. Even at the current pace, every block in the city won’t be able to have some type of improvement added until around 400 years from now.

“What we hear most often is that people want more sidewalks and walkways delivered in more places, more quickly,” Ali said. “Using quick-build design approaches, like using asphalt, allows us to extend more walkways to more places more quickly to meet that demand. Feedback we’ve received about the type of new walkways and sidewalks — both concrete and quick-build — has generally been positive, and residents consistently share appreciation for safer, more predictable walking routes. We also use community feedback to help inform future design decisions. Quick-build walkways allow us to extend safer walking connections to more people more quickly throughout the city.”

In a city lacking the resources to add a concrete sidewalk to every block that needs one, the tradeoffs that exist are real and tangible: a full block of sidewalk built on 21st Avenue could mean several other blocks where a pathway isn’t able to be built elsewhere. But to Lee and many of her neighbors, the asphalt path that is planned is another example of the city’s South End being shortchanged, an additional manifestation of decades of underinvestment.

Lee is hopeful that the city can reverse course and take a more holistic view of sidewalk construction, rather than focusing on the number of blocks built.

“It would be disappointing to know that the city isn’t true to its word when they say that they want to engage the community, or want to be transparent about the projects that they’re building that affect true people. ” Lee said. “If the city does build true concrete sidewalks on both side of the street, I’ll be like, ‘that is amazing.’ I’ll be totally won over. I could walk with my daughters and ride our bikes along the street and feel awesome knowing that we did that as a community.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.