Nearly a full year beyond a state-mandated deadline, the Seattle City Council adopted a new long-term growth plan on Tuesday, laying out policies intended to guide and accommodate housing and job growth through 2044. Aside from tweaks made by the council, the new Comprehensive Plan represents outgoing Mayor Bruce Harrell’s vision for Seattle’s future — a small step beyond the “urban village” strategy that has been in place since the 1990s.

Harrell’s framework has faced significant criticism for not going far enough to accommodate future housing growth in Washington’s most populous city, including from the City’s own planning commission.

On top of the 8-0 vote to adopt the plan itself, another unanimous vote will put new zoning standards in place across the city’s lowest-density zones, with beefed-up allowances added by the council that will allow builders to make small-scale multiplex development more easily pencil out as feasible. One local architect described those new standards as leading to Neighborhood Residential (NR) zones that are “fundamentally changed.” Formerly known as single family zones, NR areas account for nearly three-quarters of the land in Seattle zoned for housing.

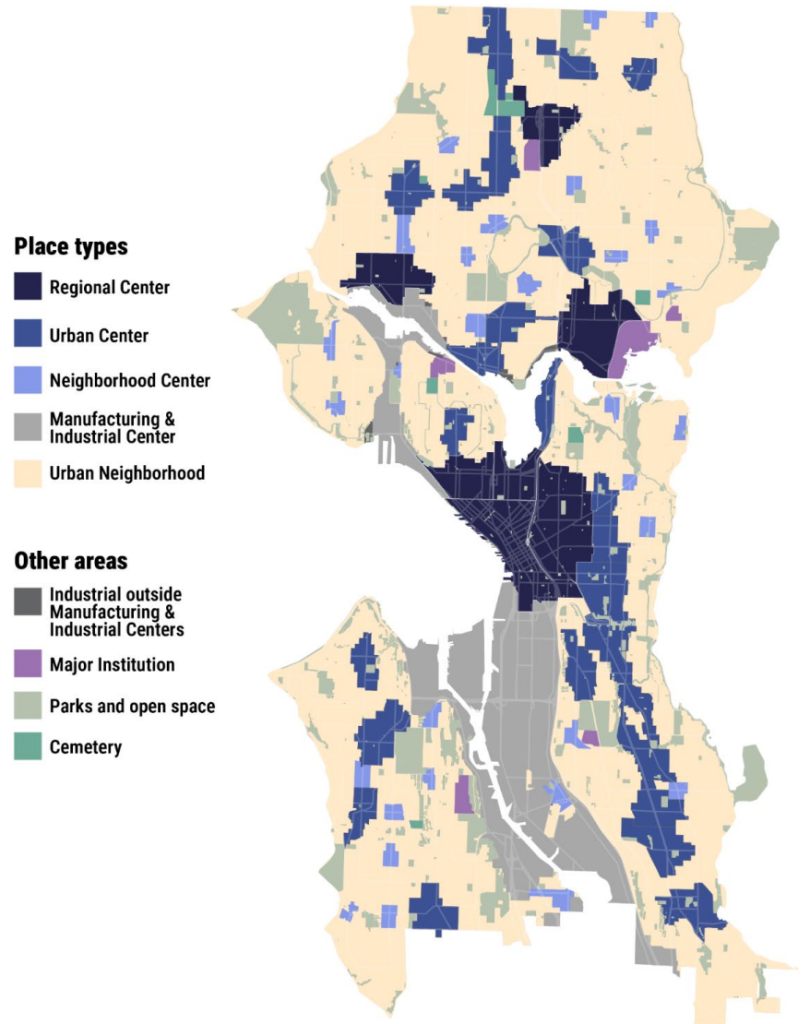

Nonetheless, Seattle’s biggest housing debates still lie ahead. While the new Comprehensive Plan lays out the locations for 30 new neighborhood centers — areas of higher-density zoning, mostly focused around existing commercial districts — the exact zoning standards for those areas won’t be adopted until next year as part of the plan’s second phase. That phase also includes lifting apartment bans in the blocks directly along some of the city’s most frequent transit corridors, something that is much less prescribed by the plan and therefore more up for grabs.

Beyond that, the City has pledged a phase three, which will look at zoning changes to “urban center” neighborhoods that are already Seattle’s densest areas, like Northgate, Capitol Hill and Alaska Junction.

“When I talk to our neighbors about the Comp Plan, I often say that it’s the wonkiest thousand-page document that has such a deep impact on our day-to-day lives, because at the heart of this, the Comprehensive Plan is about how we will live our lives: where people can live across our city, how we will ultimately move through our city, and it represents our shared future,” Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck said ahead of Tuesday’s vote. “This update to our Comprehensive Plan represents such an important start to make Seattle a more affordable place to live, while also reconciling with our racist history of land use within the city.”

At first glance, the timing of passing a Comprehensive Plan now might look like a missed opportunity for the new mayoral administration, led by Mayor-elect Katie Wilson. On the campaign trail, Wilson had been critical of Harrell’s proposed plan for not going far enough, and it now represents the new floor which her administration can build upon. Rather than the plan itself, the biggest limiting factor in 2026 will be how quickly Wilson’s administration can conduct environmental review to make additional changes. In some ways, not having to worry about adopting a major Comprehensive Plan update at the same time will likely prove to be a gift.

“If we only plan for housing to match expected population growth, that’s a recipe for continued tight housing markets and unaffordable rents, with homeownership remaining out of reach for most,” Wilson told The Urbanist’s elections committee earlier this year in explaining why she supported going further than Harrell did. “We should be adding more neighborhood growth centers, expanding the definition of ‘near transit,’ granting social housing the same density bonus that other types of affordable housing get, eliminating parking minimums, fix the stacked flats bonus so it actually results in building stacked flats, exempt smaller projects from [Mandatory Housing Affordability] fees so they will pencil out, etc.”

The city council also came up against the barrier of the environmental review process when trying to pass their own amendments. Rinck’s proposal to restore eight neighborhood centers that had been explored earlier in the plan’s development wasn’t able to make it in for that reason, and instead it ended up in a resolution which also passed Tuesday, laying out a laundry list of changes for the city’s Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) to work on in 2026.

OPCD will have to juggle those priorities on top of any new goals added by Wilson, which could ultimately prove a challenge given the department’s limited staffing levels.

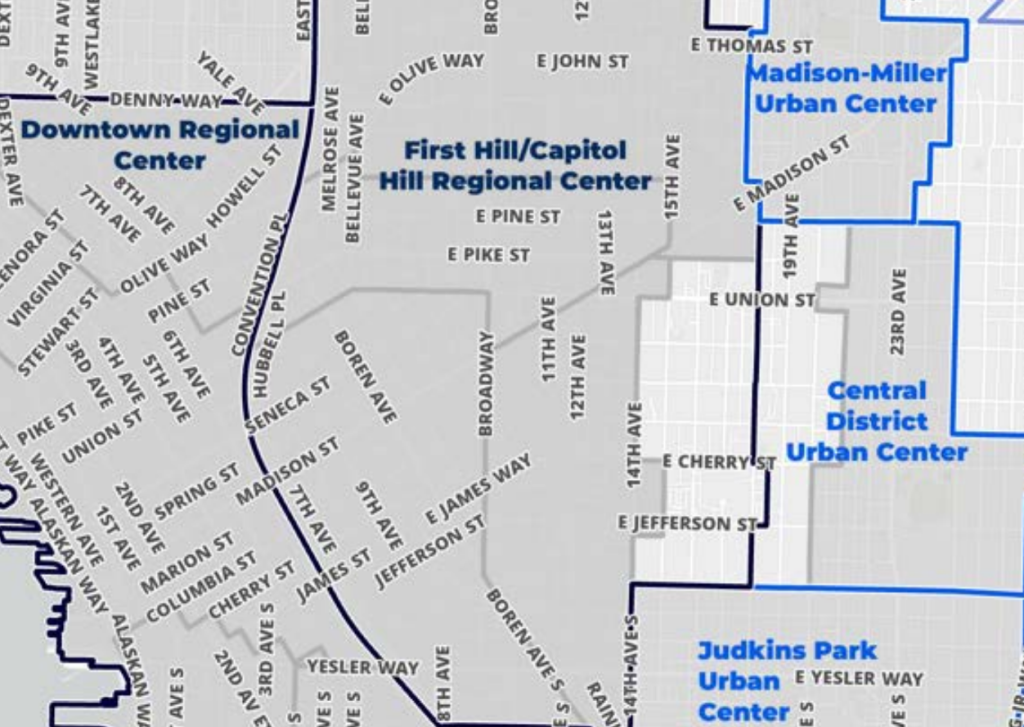

The council did make one substantive change to the plan before its final vote, removing a small area west of 18th Avenue that had been set to be added to the First Hill/Capitol Hill Regional Center. Filling in a “donut hole” of lower density within one of the city’s most transit-rich neighborhoods had been proposed by the Harrell Administration, but Comprehensive Plan Committee Chair Joy Hollingsworth raised concerns about lumping that area in with Capitol Hill’s regional center instead of the Central District urban center, which will extend east of 18th. Keeping a boundary at 18th was seen as essentially splitting this historically Black neighborhood in two.

Hollingsworth had intended to put forward an amendment moving all of the area into the Central District urban center, but that amendment would not have come with enough public notice to be legal.

“The intention behind this, the second phase to this, is during Phase Two of the Comprehensive Plan, is to then post a 30-day notice for us to upzone that area, particularly for that to be the Central District Urban Center,” Hollingsworth said.

Despite the fact that OPCD spent years holding open houses, attending community council meetings, and taking feedback on the proposed plan, Comprehensive Plan Committee Chair Joy Hollingsworth pledged even more outreach around the plan’s second and third phases. An alleged lack of outreach on the plan had been a concern raised by Councilmember Maritza Rivera and by Cathy Moore, who resigned from the council earlier this year. But to many housing advocates, those concerns seemed to come from a place of assuming that the City should be responding more vigorously to incumbent property owners who wanted to see the plan scaled back, even more than it already had.

“We will have better outreach to everyday people, from our [OPCD] department to our office as well, to make sure people’s voices are heard and that we get everyone’s voices across the city, that is really important” Hollingsworth said.

Eddie Lin, the council’s newest member who took office just three weeks ago, framed the decisions made around zoning and transportation as part of this process as foundational to how the city achieves its goals — or doesn’t. Lin will chair the land use committee next year, barring a committee shakeup next month.

“The reason we are in the position we are in today, around affordability, around homelessness, around unsafe streets is because of mistakes that we have made in the past. And this doesn’t solve all of those mistakes, but I think this puts us on a better path, moving in the right direction” Lin said. “This past weekend, we lost the life of a bicyclist in Beacon Hill, and that was pretty devastating for our community. And if we want to make real progress on Vision Zero, we have to think about how we’re addressing our built environment, how we’re building dense walkable neighborhoods with good infrastructure for pedestrians, for bicyclists, and that we’re transitioning away from our over-reliance on vehicles as our primary mode of transportation.”

While the biggest housing discussions are still in the future, finally adopting the Comprehensive Plan is a big lift, and the city won’t have to consider another major update to its growth plan under state law until 2029, as part of the Midpoint Comprehensive Plan Update. But given the new administration’s focus on housing affordability and sustainable transportation, the issues laid out in the plan will likely remain front-and-center.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.