Sound Transit is dismissing the idea of a single downtown tunnel too quickly.

In late August, Sound Transit revealed a financial crisis: a shortfall of more than $30 billion in its operating and capital budget through 2046. Since then, Sound Transit staff have steered the board to consider a variety of scope reductions except the biggest ticket item: tabling a second light rail tunnel through Downtown Seattle and redesigning Ballard Link to use the existing tunnel.

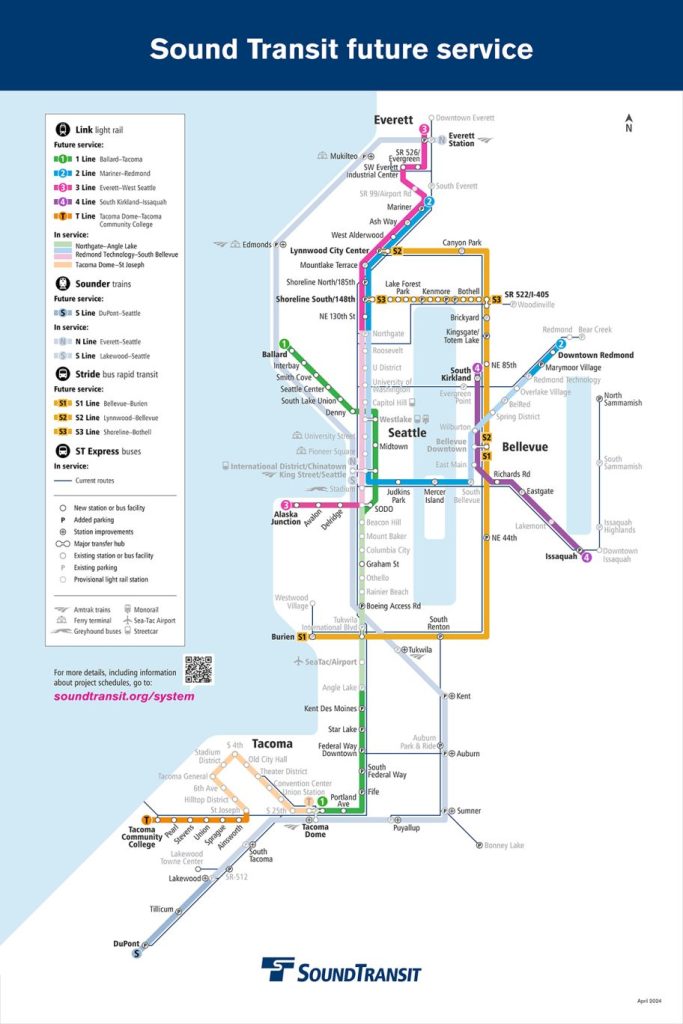

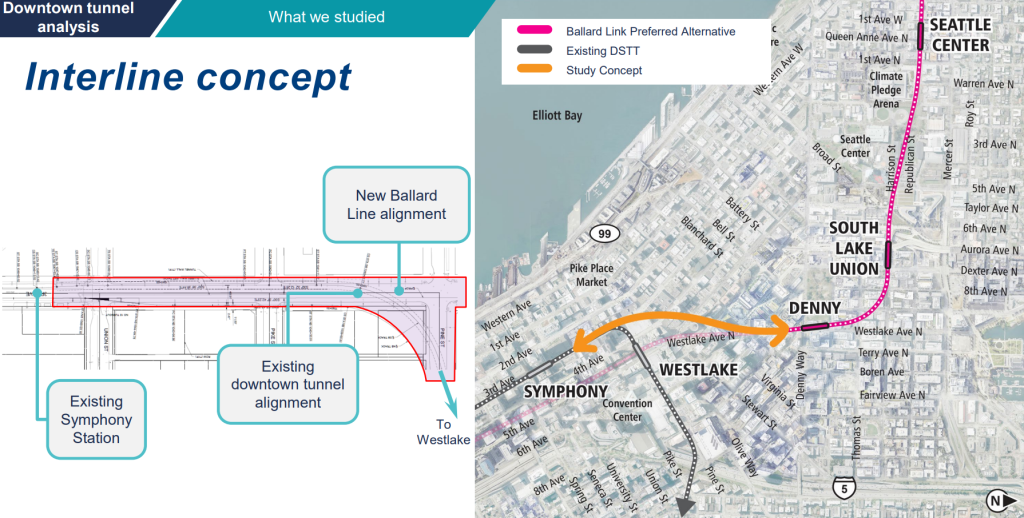

Cutting the second downtown tunnel (for now) could save as much as $4.5 billion, according to preliminary estimates by agency staff. Under that scenario, three lines would run though the existing downtown Seattle tunnel: the future Tacoma-to-Ballard line, the Redmond-to-Lynnwood line, and the West Seattle-to-Everett line. That would be a considerable amount of train traffic for one tunnel, but the challenge is not insurmountable.

In proposing scope reductions, Sound Transit’s staff is forcing Puget Sound transit riders, car commuters, board members and elected officials to behave like crabs in a bucket – fighting to hold on to their preferred projects while the rest of the region loses. And, given what Sound Transit staff are presenting to the Board of Directors, that is an understandable reaction. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Sound Transit is about to trade billions of dollars and a decade of delay for capacity we don’t need yet, while starving the rest of the region of the transit we need now. Massive overruns and delays are being justified instead of returning to first principles: asking how to deliver the system voters approved, and transparently weighing the design, financial, and operational tradeoffs required to make it happen.

To right the ship, the Sound Transit board should do four simple things and one hard thing:

Asking how, not why:

The board and advocates are spending too much time asking “why” things cost so much instead of asking “how” to deliver the project presented to voters. “Why” invites justification, “How” invites problem solving.

Once you have the “how,” then the job of Sound Transit staff is to deliver a realistic and transparent set of the tradeoffs so that the Board can then ask the “should” question – as in, should we take one course of action or another?

Reform approach to construction impacts

Sound Transit’s planning culture is built around avoiding disruption during construction, not minimizing it. The result is a bias toward building transit where it is convenient for construction rather than where it maximizes access, speed, and ridership. That mindset is unnecessary and costly. Other cities have shown that disruption can be short, surgical, and manageable, even at the busiest intersections on Earth.

London’s Victoria Line is a perfect example. When engineers needed to build the Oxford Circus interchange —one of the most crowded pedestrian crossroads in Europe—they staged construction in two concentrated weekend closures years apart. The result is a high-value station, in a high-value location, delivered with a fraction of the disruption Sound Transit claims is unavoidable. This is the product of asking “how.”

Do not exaggerate disruptions during Seattle tunnel work

Three years of disruption to retrofit the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel (DSTT) in lieu of a second tunnel is a red herring to scare people away from asking hard questions about the second tunnel. Granted, some significant impacts will be unavoidable, but once the plan is refined, the retrofit is unlikely to cause rider impacts anywhere near that intensity.

When Hurricane Sandy flooded the L line and the Canarsie tunnel in New York City, the original plan called for a 15-month full closure disrupting 400,000 daily riders. MTA sharpened their pencils and the project only required nights and weekend closure and was completed in 15 months (And New York’s tunnel was 90+ years old and submerged in saltwater by Sandy).

In 2013, Chicago shut down the south branch of the Red Line for nine months and completely rebuilt 10.2 miles of the Red Line for $425 million ($600 million in 2025 dollars). Replacing 1.3 miles of the transit tunnel’s ventilation and signaling systems will not take four times as long.

It’s not that Seattle’s tunnel retrofit would be the same project. Rather, Sound Transit’s estimate is not credible engineering. It’s political positioning. And it prevents the region from having an honest conversation about how to use the infrastructure we already own to unlock faster, cheaper delivery of all the projects voters approved.

Second tunnel is a question of when, not if

The constraint on Sound Transit’s light rail capacity is not the DSTT — at least once the tunnel is properly modernized. It is at-grade crossings in the Rainier Valley and Bellevue. Until at-grade crossings are eliminated, trains are limited to frequencies of about six minutes on these two branches.

Once Ballard Link is built out with a second tunnel, Sound Transit projects a total of 30 to 36 trains per hour per direction through downtown. A revamped DSTT could handle at least 36 trains per hour (the Victoria Line – opened in 1968 – runs 36 trains per hour today). The second tunnel builds double the capacity Sound Transit estimates it will need in the 2040s.

Delaying the second tunnel and upgrading the existing tunnel, building West Seattle Link, Ballard Link, and getting to Everett and Tacoma will improve access to Downtown Seattle, Tacoma and Everett for more people, more quickly than a second tunnel.

What’s more, the second tunnel that the agency proposes today does not fulfill its original intent: a regional transit hub in the Chinatown-International District (CID) and a Midtown station, near Seattle’s Central Library. A single tunnel restores the promised regional transit hub and high-quality access to the CID, with a fraction of the local impacts.

The challenge is “how” to make the DSTT work, not “why” it won’t. Until we fix the real chokepoint (MLK Way), a second tunnel isn’t needed. The second tunnel is the wrong constraint, at the wrong time, at the wrong price. And when we do make this investment, it must connect existing neighborhoods clamoring for access, not hypothetical redevelopments.

The challenge: Build better transit cheaper

Building better transit cheaper is the hard challenge for Sound Transit to take on. Right now rail transit in the U.S. costs more per mile than anywhere else in the world and Sound Transit 3 projects cost twice as much per mile than anywhere in the U.S. outside New York.

NYU’s Transit Costs Project has done a great job documenting why: overbuilt stations, gold-plated utility relocation, excessive environmental process layering, reluctance to disrupt traffic, overuse of consultants instead of in-house design, layered political veto points, endless “scope creep.” No single line item explains the billions—it’s death by a thousand cuts, each defended as individually reasonable, but collectively catastrophic.

Every dollar we spend on a new, redundant downtown tunnel is a dollar not spent finally providing grade separation in the Rainier Valley – making our system faster, more reliable and safer for South Seattle, plus riders from South King County and Pierce County. It is a dollar spent not getting light rail closer to Paine Field faster, relieving overcrowding at SeaTac and connecting to Snohomish County’s economic engine. It is a dollar spent not connecting West Seattleites and Ballardites to Downtown Seattle and other regional job centers on the Eastside, in Tacoma, and Everett.

Some will call this a “scarcity” mindset. The reality is, in Seattle saving money on transit doesn’t mean you get less transit. It means you get more transit.

This is not a retreat from the vision voters endorsed. It is a commitment to delivering it faster, cheaper, and with greater fidelity to rider needs.

Many residents across the Puget Sound region want to prove that government can do big things. Doing big things does not mean spending a lot to get a little. It means delivering a lot, building public trust through competence, and earning support for even more ambitious projects.

The second tunnel will still be needed someday. But building it now — before fixing the real bottlenecks — would be a multibillion-dollar self-inflicted delay that harms the case for more transit locally and nationally.

Scott Kubly

Scott Kubly was the Director of the Seattle Department of Transportation under Mayor Ed Murray from 2014 to 2017. Prior to SDOT, Scott held senior leadership roles in the Chicago DOT and Washington DC DOT. He also led a team of Office of Management and Budget analysts for Mayor Adrian Fenty in DC and worked for the Washington Metro (WMATA) for five years leading capital financial planning strategy.