On Saturday, January 31st, a coalition of local non-profits kicked off a grassroots campaign to accelerate construction of 250 additional miles of key Seattle bicycle routes by 2025. The city already has 135 miles of bike infrastructure, and momentum is building to work faster on building a comprehensive network that makes bicycling safe for people of all ages and physical abilities. Cascade Bicycle Club and Seattle Neighborhood Greenways are leading the effort, and also worked to update the city’s Bike Master Plan last year. And three city council members attended the kickoff event, indicating there is already political support. The campaign’s main goals are to pass the next transportation levy, elect pro-bike city council members, and continue advocating for priority projects.

On Saturday, January 31st, a coalition of local non-profits kicked off a grassroots campaign to accelerate construction of 250 additional miles of key Seattle bicycle routes by 2025. The city already has 135 miles of bike infrastructure, and momentum is building to work faster on building a comprehensive network that makes bicycling safe for people of all ages and physical abilities. Cascade Bicycle Club and Seattle Neighborhood Greenways are leading the effort, and also worked to update the city’s Bike Master Plan last year. And three city council members attended the kickoff event, indicating there is already political support. The campaign’s main goals are to pass the next transportation levy, elect pro-bike city council members, and continue advocating for priority projects.

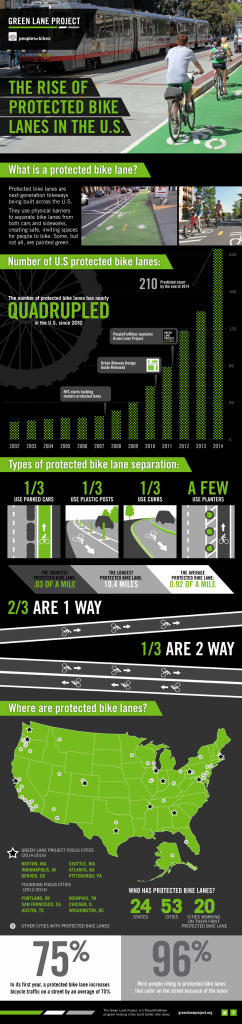

The campaign, known as Connect Seattle, is focusing on the three safest types of bicycle facilities: protected bike lanes (PBLs), greenways, and regional trails. This leaves out standard bike lanes and share-the-road configurations that are only created with paint on pavement, which provide little protection against vehicles. PBLs, in contrast, provide some sort of traffic separation, whether by flexible bollards, concrete curbs, or planter boxes. Greenways, as defined by the City of Seattle, are quiet residential streets designated as bicycle routes with traffic-calming features like stop signs, speed bumps, and roundabouts. Off-street regional trails are completely separated from vehicles and are also open to pedestrians.

The city’s current bicycle network consists of all of these facility types, but they are mostly a sporadic patchwork. The city’s Bicycle Master Plan (BMP) envisions a complete 600-mile system to be built out over the next 20 years. Connect Seattle wants to get 250 of the most important miles in place within the next 10 years. Connecting the entire city with safe and comfortable bike routes will cater to the largest group of potential bike riders: the willing but wary. They’re interested in bicycling for transportation purposes but are turned off by the thought of riding in traffic.

There are three other citywide issues at play. Starting this year seven city council seats will be elected by district, giving neighborhood groups more direct representation. There is an emerging nationwide movement called Vision Zero that aims to eliminate all avoidable traffic injuries and deaths within the next few decades.

Finally, in 2016, voters will decide on a new transportation levy to replace the expiring Bridging the Gap property tax and commercial parking tax; some 80 percent of bike infrastructure funding over the past nine years has come from this levy. On this topic, Seattle City Councilmember Mike O’Brien told me he anticipates citizens demanding a mixture of investment: “In general, I think residents are looking for projects that create connectivity in neighborhoods – integrating bike, pedestrian and transit infrastructure alongside road improvements. I also think there is a chance to invest in a few of our larger capital projects that communities are organized around, like the Northgate Pedestrian Bridge.”

Brock Howell, policy and government affairs manager for Cascade Bicycle Club, told me, “We recognized that Cascade’s strength is in its members…the caring neighbors who are willing to work for a better future in Seattle—if we provide them with the tools to make it a reality.” To that end, the campaign has identified a number of priority projects in key neighborhoods and formed local groups to speak up for them. Some of the projects are controversial or costly and will require sustained advocacy by residents to convince the city’s transportation department (SDOT) and the city council that they’re worth pursuing. Drivers and businesses will continue to provide the most resistance, though they often use zombie arguments that don’t account for the environmental and economic benefits of bicycling. Expanding the bike network may require some lane reductions, but it will actually decrease traffic congestion by convincing and enabling a significant number of people to bike for work, school, errands, and other trips instead of driving.

Many of the projects have been in the works for years and just need a final push to go through, while others are conceptual. As Howell notes, “Not every bike project is big or expensive—and we’re seeing more and more community support for bike projects.” Streetsblog credits Seattle Neighborhood Greenways with changing the language of public discourse.

The Big Projects

Perhaps the most important project in north Seattle is the Northgate Pedestrian and Bicycle Bridge that will span I-5 to connect the future Northgate light rail station with North Seattle College and a cluster of medical buildings. It’s estimated the bridge would carry 7,000 people a day, compared to a 700-900 space parking garage that is also planned. The City of Seattle and Sound Transit have each committed $5 million to the $25 million bridge, with a July 2015 deadline to find the rest. City Councilmember O’Brien, who is also a member of the Sound Transit board, said, “there will be a motion at our March meeting to defer the funding deadline to February 2016.”

Also related to light rail is the complex Portage Bay Bridge and Montlake Cut crossing. After a strong push by neighborhood groups, the state department of transportation has committed to including a bike and walking path across the replacement bridge over Portage Bay, part of the unfunded SR-520 reconstruction project between I-5 and Lake Washington. At issue is how the area’s bike network will navigate busy Montlake Boulevard and span the Montlake Cut to connect with the Husky Stadium light rail station, opening a year from now, along with the University of Washington campus and the Burke-Gilman trail. Options include widening the Montlake Bridge or building a new pedestrian and bike drawbridge. A new land bridge and freeway lid over SR-520 will also help knit the area together. This project is regional in scope, as this area is where people can transfer to buses bound for Eastside communities.

Ballard has two key projects that have been discussed for years. Most contentious is the Ballard “missing link”, a 1.5-mile gap in the 27-mile-long Burke-Gilman Trail that has long exposed cyclists to heavy truck traffic. Funding and design are in place, but in 2011, several industrial businesses sued to stop the project and suggested an alternative route. The City is now waiting on a consultant’s environmental impact assessment before deciding how to proceed. Another major issue in this growing neighborhood is the narrow Ballard Bridge, which is 98 years old with extremely constricted 3.5-foot-wide sidewalks. In 2014 the City studied several options for cantilevering widened paths, priced in the range of $20-30 million. Seattle Bike Blog has suggested a much more elegant road diet solution. Further study is ongoing.

The 1.2-mile Westlake cycle track will be built this year to connect Fremont and South Lake Union along Westlake Avenue. Currently, cyclists compete with cars, trucks, and pedestrians in a long parking lot that is heavily used by waterfront businesses. A group of those businesses sued to prevent implementation of the entire Bicycle Master Plan, but dropped the suit in early 2014 after negotiating with the mayor’s office. The new project, finally getting done after a big push from local activists, will minimize loss of parking and create a continuous route for commuters. It’s an example of high quality design and community collaboration. Across the water, an Eastlake Avenue protected bike lane would facilitate safe riding between the University District, Eastlake, and South Lake Union neighborhoods.

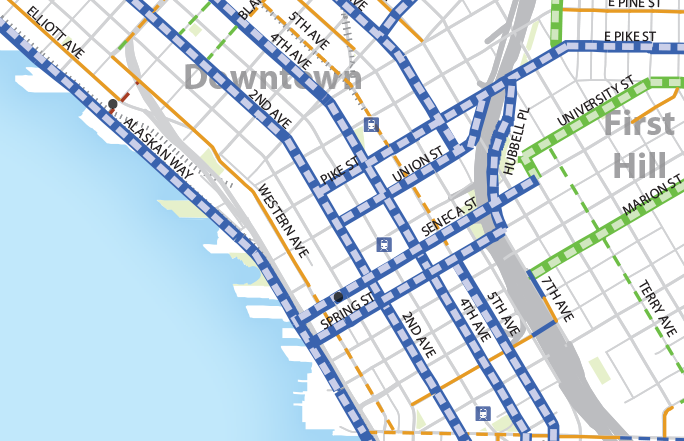

Over the next five years, the City plans to build out a complete downtown protected bike lane network. The city took a bold first step with the 2nd Avenue two-way PBL last fall, which included removing a travel lane and installing bike-specific traffic signals. The city’s Bicycle Master Plan identifies PBLs on 2nd, 4th, 5th, and 7th Avenues, and Pike, Union, Spring, and Seneca Streets. I visualized part of this network in the site plan for my Metro Tract project, but the actual designs will be studied this year. Amazon has pledged to fund two blocks of the PBL on 7th Avenue in exchange for alleyway vacations, and the City received $5.8 million in federal funding for much of the rest of construction earlier this year. Downtown Seattle will soon be as bike-friendly as Vancouver’s central business district.

In the southeast, the Rainier Avenue safety project will take a hard look at a four-mile stretch of the most dangerous street in the city, which sees an average of some 330 collisions per year. It’s ripe for an increase in bicycling because it’s a direct and flat route to downtown that links some of the city’s less prosperous neighborhoods. As Howell says, “All neighborhoods, no matter income or class, deserve to have safe streets,” and Cascade is collaborating with Bike Works and the local Greenways chapter to ensure it works for all users. The project started last fall, and SDOT is expected to present draft design solutions this month. Changes will likely include channelization, a lowered speed limit, and improved pedestrian crossings. Some construction could begin as soon as the end of this year.

A monstrous five-way intersection in West Seattle is a major physical and temporal barrier to cyclists, taking several minutes to cross in any direction (and enough time to make a breakfast burrito, apparently). Fixing it would encourage new riders to make the connection between the Alki Trail and the Duwamish River Trail to downtown Seattle and beyond. SDOT has gotten the ball rolling with community workshops, and one option that has emerged is a bike and pedestrian bridge to elevate people above the traffic.

Among all of these major endeavors are numerous small but no less important projects that will be the focus of Connect Seattle’s neighborhood chapters. Residential greenways and shared streets will provide calmer routes adjacent to major arterials. Standard bike lanes will still be appropriate on low-traffic streets and for funneling people on bikes to protected routes. In addition to public education and awareness, physical features like bicycle traffic signals, green paint at intersections, bike boxes in front of stopped traffic, and advanced signaling will contribute to a safer riding environment.

Significantly, no less than three City Council members attended the Seattle Bike Summit kickoff event on Saturday. Mike O’Brien, Sally Clark, and Tom Rasmussen all came by to lend words of support. Chief Traffic Engineer Dongho Chang, who has been instrumental in fostering SDOT’s progressive transportation mindset, was also in attendance. O’Brien recalled being in awe of seeing a sharrow for the first time on Seattle’s streets only a few short years ago, and marveled at how far the city has come already. He concluded by noting the three keys to success for any advocacy campaign: champions in public office and on the ground; accountability of elected officials; and trade-offs to gain the public’s favor.

Connect Seattle is off to a running start. You can view a draft fact sheet (PDF) of the key projects, though note that it doesn’t represent the official policy positions or strategies of Cascade Bicycle Club and was only made for use at the Connect Seattle summit. Visit the campaign website and find your nearest neighborhood group to get involved.

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist, the personal blog of Scott Bonjukian. He is a graduate student at the University of Washington’s Department of Urban Design and Planning.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.