Mayor Durkan is looking to local tech talent to address pressing issues, but the City’s commitment to data privacy may limit the reach of technological innovation.

Technology’s influence on urban planning and city management is growing at light speed these days. Data collection, mapping and analysis tools, crowdsourcing platforms, and app-based services that track user trends are proliferating in number and scope. In the not-so-distant future such piecemeal technologies may all be stitched together by smart city frameworks. According to Technopedia, a smart city uses information and communication technologies to improve the performance of urban services with the goal of enhancing the quality of life for its residents. Worldwide investment on smart city initiatives has increased substantially in recent years and is estimated to grow to over 34 billion (USD) in 2020.

Despite being an international hub for big tech, Seattle has not received a smart city designation, nor does it appear to be in the running anytime soon. A review of several different rankings shows that Seattle routinely does not even make the top 10 for smart cities in the US. In fact, Seattle has has been outpaced in adopting technological innovations by not only the usual suspects, cities like Boston, San Francisco, Portland, but also surprise metros such as Tulsa, Oklahoma, which has gained national recognition for for its Urban Data Pioneer program.

Why is Seattle lagging behind other cities in adopting tech solutions?

At least one answer for this question can be found in the City’s commitment to data privacy. Seattle has made a name itself as a leader in the data privacy movement; in 2015, Seattle established an official privacy policy intended to ensure city government offices maintain “good data practices and data stewardship.” One of these practices is use of de-identification techniques, which scrub all personal information from open data released to the public. At the same time, even after data is scrubbed, the “mosaic effect” created by multiple overlapping data sets can still reveal private information unintentionally.

To further increase privacy protections, Seattle City Council passed what it called the “strongest-in-nation” surveillance technology transparency ordinance in 2017. Citing community concerns about possible misuse of surveillance data by the Trump administration, Councilmember Lorena Gonzalez, who sponsored the ordinance, said that “challenges between community and police departments, and uncertainty in our immigrant and refugee communities” necessitated that the Council “behave in a way that supports and enhances the public trust.”

Through the use of cameras, sensors, and GPS devices, often called the “internet of things,” smart cities rely on what can broadly be considered surveillance to collect data that informs city decision making.

As a result societies with fewer privacy restrictions, like Singapore, have moved forward quicker with implementation of such technologies. Singapore, which tops the world’s smart city rankings, is open about its attempt to track all aspects of urban life, including human behavior. Data collected from thousands of devices throughout the city is directed to specific government programs and then fed into a central platform accessible to all government agencies and used for administrative decision-making and planning efforts.

Such a comprehensive and highly centralized effort would be impossible in Seattle under current privacy policy, and according to some, that might not be a bad thing. Toronto-based Sidewalk Labs was commissioned by Google to help create Alphabetville, which it dubbed the “first neighborhood built from the internet up.” Since then Sidewalk Labs has faced criticism for its surveillance and data collection techniques. A 2018 article in The Atlantic called Alphabetville, Google’s Guinea Pig City. Such statements were well received by some smart city skeptics, who have gone so far as to forecast that smart cities will be the end of democracy

Will the new Innovation Advisory Council bring Seattle a step closer to becoming a “smart city”?

Last August, in an Executive Order that cited the fact that “software developer is Seattle’s most common job,” Mayor Durkan called for the creation of an Innovation Advisory Council (IAC) that would “harness the expertise of Seattle’s best technology organizations and brightest minds towards solving the challenges of our City.”

The innovation council formed a few months after leading tech companies like Amazon pressured Mayor Durkan and the city council into repealing a freshly passed employee hours tax or “head tax” that would have brought in nearly $250 million for affordable housing and homelessness services over five years. In the aftermath of the appeal, critics wondered if tech companies would engage constructively or only snipe from the sidelines and block revenue sources?

The innovation council gives tech an opportunity to engage. Moreover, this move may indicate that Mayor Durkan is interested in putting the City on a new path in regards to technological innovation and data privacy, since almost all technology aimed at improving cities involves data collection.

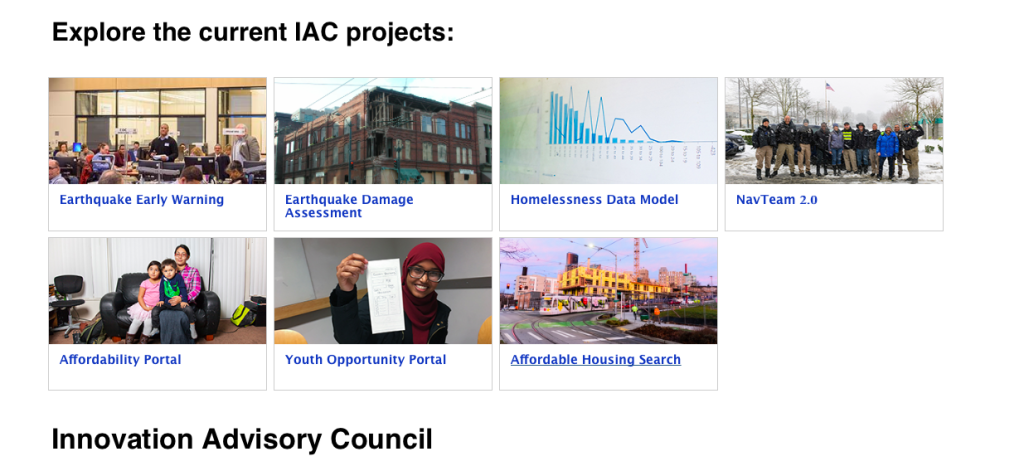

In the subsequent months, nearly 60 people from City of Seattle departments met with IAC members to determine how to best match city projects with IAC members’ skills. Using this information, seven “Phase 1” projects were identified, including:

- Earthquake Early Warning System

- Earthquake Damage Assessment Tool

- Homelessness Data Modeling

- NavApp 2.0

- Affordability Portal

- Youth Opportunity Portal

- Affordable Housing Search Tool

A review of the recently published IAC website reveals that many of these projects are still in early development; however, it is clear increased data tracking and analysis will be a majority focus for many of the projects, including the efforts to improve services for people experiencing homelessness.

This is not a big surprise given the fact that the conversation around funding for homeless services in Seattle has recently focused on what data reveals, or does not reveal, about the effectiveness of different services. Advocates may wryly note that the package of fixes includes a tool to search for affordable housing, not a way to ensure more such housing exists. King County faces a near-term shortage of 44,000 affordable homes according to the Regional Affordable Housing Task Force commissioned to tackle the problem. There’s not an app for that, at last check.

With a budget that topped $90 million in 2018, spending on homeless services has increased at the same time that the number of unsheltered people has continued to grow. Advocates claim that while the budget has increased, it is still insufficient to meet demand given massive structural hurdles and skyrocketing housing prices. Meanwhile, skeptics believe that ineffective programs and mismanagement are to blame. Some have argued more data needs to be collected and analyzed in order to make the case for what level of public expenditure on homelessness is warranted.

According to the IAC website’s write up on homelessness:

This project will improve reporting on homeless investments, budgets, outcomes, and program model information with automated reporting. The outcome will be a functioning data solution that holds multiple complex data models for analysis.

City of Seattle

The collection of data on homeless services will offer an interesting test case of Seattle’s privacy policy. Will the City continue to uphold its high bar for maintaining privacy when it comes to creating policy for a vulnerable and often stigmatized segment of the population, or will it reduce its standards in the name of accountability and efficiency?

Moving forward, data collection on homeless services also raises the question of whether or not the public will accept a different level of privacy standards for those who access government services than those who do not. If public is comfortable with more data being collected from those who access public assistance, the result could be a two-tired system in which the more affluent are able to maintain more data privacy, while those who rely on public assistance have no choice but to let their data be collected regardless of privacy implications.

In general, new technological innovations hold the promise to be both useful and disruptive. It will be interesting to see if Seattle chooses to maintain its current stance of privacy protection or shift toward more data collection in the name of improving quality of life for residents in future years.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.