Motorists have been able to use the new four-billion-dollar SR-99 Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement tunnel for free since it opened February 4th. That will change Saturday as the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) begins tolling the tunnel. Tolling will lead to some diversion of car traffic from the tunnel to Downtown streets and that could negatively impact other road users by clogging bus lanes and crosswalks. The question is how much.

Tolls will range from $1 to $2.25 for drivers with a Good To Go pass, depending on time of day. Drivers without a Good To Go pass will pay $2 more, meaning a range of $3 to $4.25. Vehicles with additional axles will pay more. The Washington State Transportation Commission set the toll rates in October 2018, after a five-month-long public input process. WSDOT has been seeking to educate motorists with an advertising blitz building of its earlier “It’s A Thing” campaign that sought to entice people to drive in the SR-99 tunnel.

The Washington State Legislature’s financing plan for the viaduct replacement project relied on tolling to cover $200 million worth of the construction bonds and all of the upkeep and maintenance costs. Thus, removing tolling isn’t a viable option without coming up with a major new funding source. Especially since the State (or even the City) could be on the hook for all or some of the project’s considerable cost overruns after the Bertha breakdown saga.

Weaker Demand for 99 Tunnel than Predicted

In our earlier coverage, we’ve raised the issue of whether SR-99 traffic volumes will be sufficient to cover the costs, given that the highway has underperformed projections thus far, particularly in its first few months.

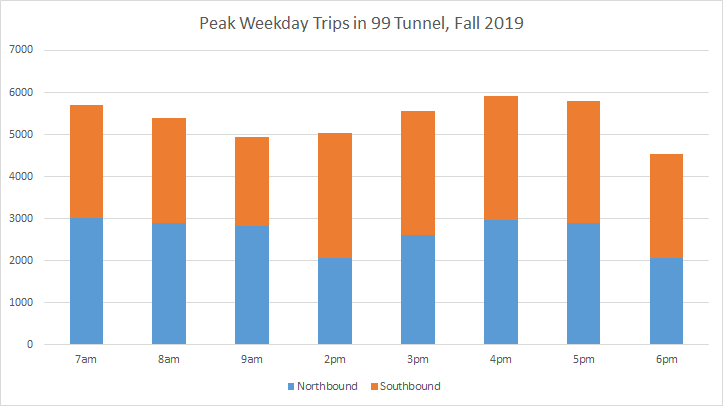

WSDOT is reporting that traffic volumes are up considerably now, but still below predicted levels of nearly 7,000 vehicles per hour. “75,000-80,000 vehicles use the tunnel on any given weekday,” WSDOT spokesperson Laura Newborn said. “Also, approximately 25,000 vehicles use the exits to city streets at either end of the tunnel on any given weekday. This means more than 100,000 vehicles use the SR 99 to/through Seattle daily.”

Traffic volumes peak at the 4pm hour according to WSDOT data, but still don’t exceed 6,000 vehicles even then. Overall peak periods in the SR-99 tunnel are averaging 5,352 vehicles per hour in the latest data we saw.

Diverting Traffic to City Streets

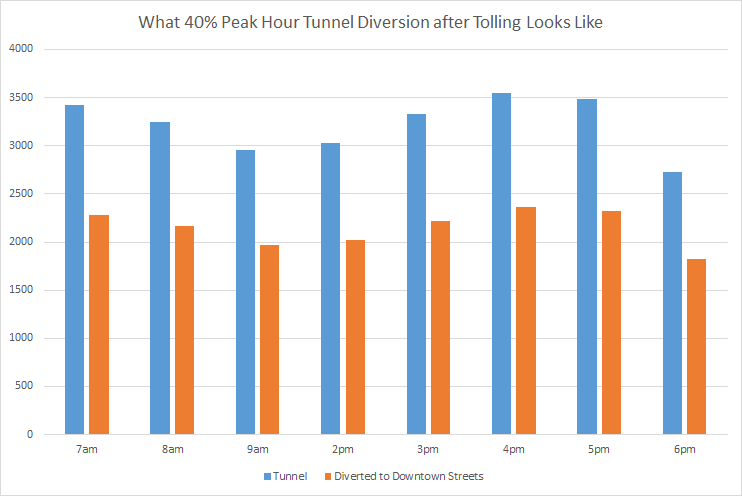

Even below projections, traffic volumes are high enough that thousands of motorists are likely to be diverted to city streets to avoid tolls–at least at first in reaction to the sticker shock of tolls.

“Our forecast suggests diversion could be as high as 35% to 40% during peak periods,” Newborn said. “However, we want to stress that forecasts are not certainties. When tolling began on 520, drivers initially diverted to other routes, but many returned to 520 over time. We expect to see something similar with the 99 tunnel. Some percentage of drivers will initially try other routes and return to the tunnel as they weigh the cost-vs-time saved in using the tunnel to get through Seattle.”

WSDOT also advised their diversion forecasts were conservative–in other words they predicted a lot of diversion in case that came to pass–for the sake of securing bonds.

“WSDOT’s forecast of tunnel volumes with tolling were part of a revenue study to make sure we were able to generate enough toll revenue to pay back $200 million in construction bonds used to build the tunnel,” Newborn said. “It’s important to note that our diversion forecasts were conservative for the bond market.”

We asked why the projections were off, and WSDOT admitted predicting vehicle demand is not an exact science.

“The forecast model over-projected the number of vehicles per hour in peak periods using the tunnel,” Newborn said. “Again, traffic modeling is not an exact science. Exits/entrances in the tunnel are different than the viaduct, but 75,000-80,000 roughly mirrors the last viaduct usage study conducted in 2014.”

WSDOT appears to be hoping that diversion is a lot less than the 40% worst case scenario so that tolling revenue is sufficient for its bond repayment and maintenance needs. Since volumes started lower than projections, there’s less wiggle room. But on the other hand, there are a few options to cover the shortfalls such as raising tunel toll rates and/or tolling city streets to drive more traffic back into the tunnel.

Could Congestion Pricing Help Balance Demand?

In fact, SR-99 tunnel tolling studies launched Seattle’s exploration of congestion pricing (or decongestion pricing if you prefer) since Councilmember Mike O’Brien and others worried tolling the tunnel could drive motorists onto City streets and worsen transit gridlock, pedestrian collisions, and pollution. Councilmember O’Brien asked for congestion pricing, and Mayor Jenny Durkan later picked up the idea as a sort of centerpiece to her climate action plan. Though she ordered a study–and Uber joined in on the act hoping to influence policy–it doesn’t appear that Mayor Durkan will meet her goal of enacting the policy in her first term at the rate we’re going.

On the other hand, if Tim Eyman’s Initiative 976 stands without the Washington State Legislature stepping in to backfill the transit cuts, there could be a stronger appetite for new revenue and an opportunity to move congestion pricing policy forward. Never waste a crisis, they say.

Ryan Packer contributed to this article.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.