Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell’s pitch to rezone parts of downtown has succeeded. The mayor had made two particular rezones for highrise housing along Third Avenue and hotels in Belltown a key part of his Downtown Activation Plan (DAP). On Tuesday, the city council approved the rezones, albeit in a split decision with a 6-3 vote.

Downtown Retail Core rezone gains approval

Approval of the residential 440-foot highrise rezone in the Downtown Retail Core wasn’t completely assured. Councilmember Alex Pedersen (District 4 – Northeast Seattle) and Tammy Morales (District 2 – Southeast Seattle) voted against the measure at the committee stage for different reasons.

Pedersen threw up opposition over potential impacts to designated and potentially eligible landmark structures as well as his view that it was a big property owner and developer giveaway. Traditionally, Pedersen has been an ardent supporter of Mayor Harrell’s downtown efforts, particularly when it comes to drug crackdowns, police hiring incentives, and sweeping homeless people.

Morales, for her part, expressed frustration that the rezone was not more focused on delivering affordable and low-income housing.

“Without a mandate for affordable housing, it’s highly unlikely that any new housing that is affordable for working people will be built as part of any new developments in this area,” Morales said on Tuesday. “And if the goal is for us to make downtown vibrant, if the goal is to make it a welcoming place for the people of Seattle, we need to be promoting proportionate, universal affordability across the income spectrum.”

The mayor’s office pursued the rezone because there has been little investment in the area in recent years and believes that it could serve as a means to disrupt “street disorder.” A report by the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) didn’t shy away from painting a harsh picture of Third Avenue and nearby streets.

“As a result of a lack of recent investment combined with the heavy volume of transit riders passing through the streetscape, there are signs of deferred maintenance, outdated facades, and street furniture in disrepair,” the report said. “These physical features negatively impact the pedestrian experience and, indirectly, the vitality of adjacent businesses.” Going further, OPCD said area property owners “reported illicit activities adjacent to their buildings, including sales of illegal narcotics and stolen goods and vandalism of property.”

A rezone, the report argued, could serve as means to counter these activities in time.

“Significant new construction activity in the area would be one way to disrupt patterns of street disorder and illicit activity,” OPCD wrote. “Construction activity for major new development often spans one to two years. The disruptive effects of construction in key blocks could be a step toward resetting existing negative activity patterns in core blocks.”

Drug dealing and fencing activities are concentrated (but not limited) to the blocks around Third and Pine, which has been a hotspot for many decades and has garnered the moniker “The Blade.” Highrise construction might succeed in disrupting the black market at that particular site, but history of hotspot policing and urban blight removal efforts suggests activity would be likely to shift elsewhere so long as there is demand, perhaps a few blocks away.

That’s why The Urbanist editorial board has pushed for a holistic approach focused on addressing the underlying problems of drug abuse and poverty rather than placing the emphasis on moving the problem around or hiding it from public view. It’s strange to think that an “open-air drug market” would be a crisis but an indoor one would not.

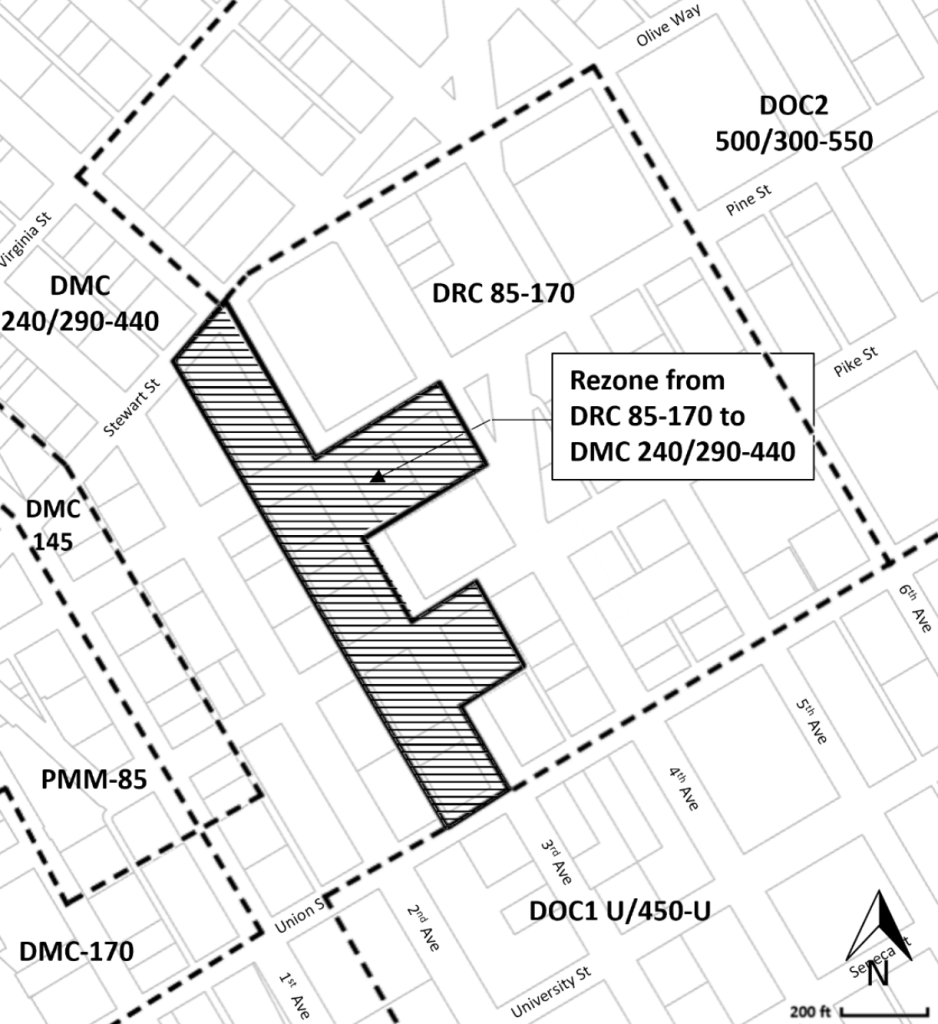

The Downtown Retail Core rezone only applies to about a dozen properties, but some of these are significant and ripe for redevelopment. The rezone boundaries generally apply to the west side of Third Avenue between Stewart Street and Union Street, though two small fingers grab a handful of lots along portions of Pine Street and Pike Street. That includes the Ross Dress for Less and former Abercrombie & Fitch buildings.

Encouraging residential highrises and a downtown school

The rezone is designed to achieve two principal goals: a lot more housing and incentives for a new downtown school. DRC 85-170 zoning on area blocks will be replaced with DMC 240/290-440, which allows for several hundred feet more in building height and heavily geared toward residential uses. Sweetening the rezone is a reduced tower spacing requirement, going from 200 feet to just 60 feet, and higher floor area ratio (FAR) limits for non-residential uses. That is the kind of zoning attractive to developers in the mixed-use business.

In a report, planning staff pointed to how elsewhere downtown zoning with a 440-foot height limit for residential towers (namely DMC 240/290-440) has been successful in doing just that in recent years. Projects usually consist of 40 or more stories with podium levels featuring commercial uses and the upper floors containing residential uses.

Planners believe that the zoning changes could facilitate somewhere between two to four major projects over the next 20 years. That could result in somewhere between 600 and 2,400 new homes in the area and help deliver $4.2 million to $8.4 million for affordable housing under the city’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program.

It’s no guarantee, but the zoning changes also provide direct incentives for a new downtown school by way of podium height and residential tower height bonuses. Seattle Public Schools are looking to consolidate and close some schools as attendance rates fall, but perhaps incentives could help grease the wheels in realizing a long-time goal of creating a primary and secondary school in the heart of downtown, where both are currently lacking. Enticing development bonuses couldn’t hurt, but it still could be an expensive proposition.

In committee, Pedersen opposed changes that would remove listing five designated and eligible landmark structures in the area for facade protection. Those protections only applied to structures in DRC zones, not DMC zones. But the protections were mostly redundant since four of the structures in the rezone area are already protected under the city’s Landmarks Preservation Ordinance and one other would be eligible for designation and protection whenever a major project moves forward.

Councilmember Andrew Lewis (District 7 – Downtown Seattle) was a very strong supporter of the rezone legislation even though he wasn’t part of its committee review. He asked to be made a co-sponsor of it, and had pushed the idea back in April when the Mayor first outlined his downtown activation vision.

“By putting a large concentration of additional residents in our downtown core, we are creating demand for new storefronts, we are creating the viability and the potential for amenities that cater to residents like grocery stores like drugstores,” Lewis said. “We are enhancing public safety by putting the informal guardians of public space and more eyes on the street because we have residents in places where currently once commuters and tourists leave the streets in many cases can be deserted.”

Lewis also critiqued the central business district zoning approach that Seattle has long clung to.

“Housing in the downtown core, to a certain extent, is sort of unplanned, almost like a doughnut,” Lewis said. “We have a lot of housing in Pioneer Square, a lot of housing in Belltown and South Lake Union. But the downtown retail core itself does not have as significant of a concentration of housing as the economic core of our city should have.”

Despite Councilmember Kshama Sawant (District 3 – Capitol Hill, First Hill, and Central District) joining Pedersen and Morales to oppose the Downtown Retail Core rezone, the full council could passed it on a 6-3 vote.

“I do not oppose upzoning these properties, but I believe the city could get a lot more from these developers in exchange,” Sawant said.

Belltown hotel zoning incentive finds approval

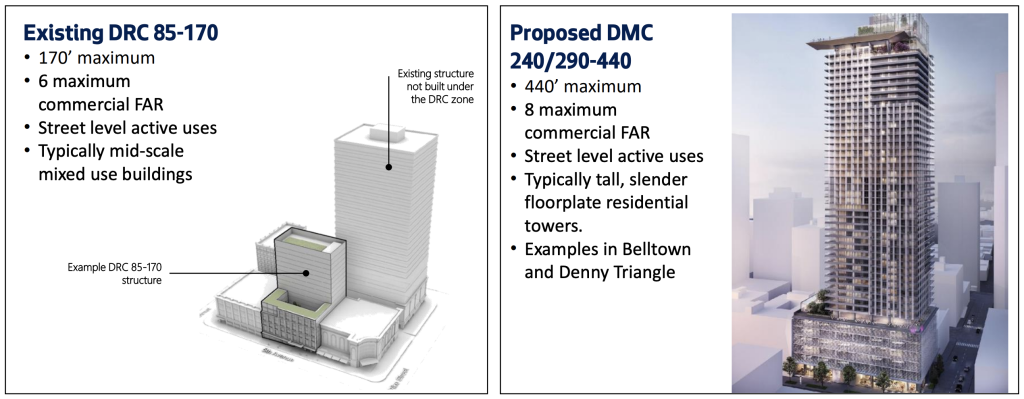

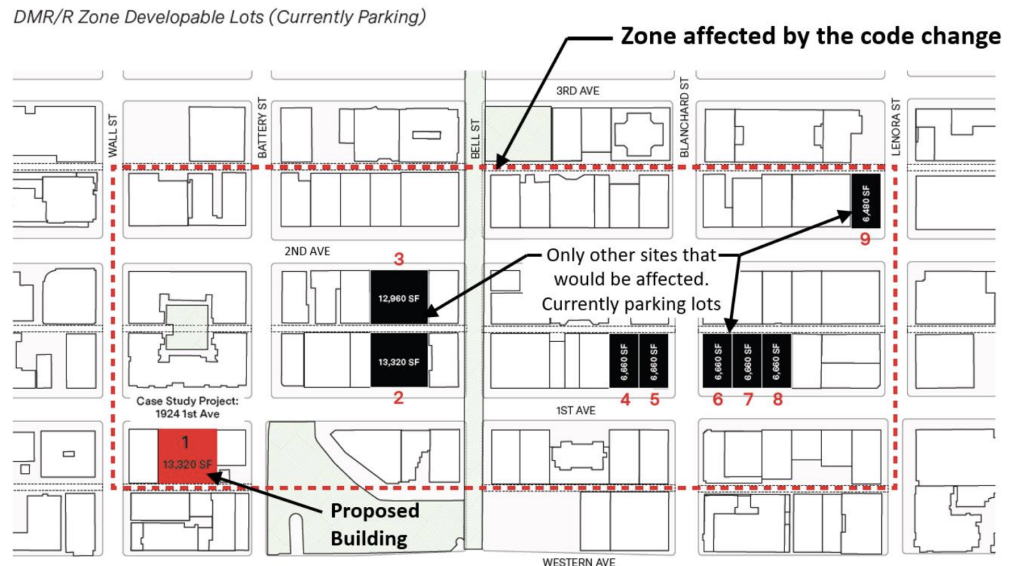

In Belltown, the mayor sought a rezone on First Avenue and Second Avenue between Wall Street and Lenora Street with the goal of allowing hotel uses. The rezone area covers about eight blocks and has nine vacant properties currently used as surface parking lots. Most of them are large enough to support development of larger structures.

In a pitch to city council, planning staff reported that hotel occupancy rates have surpassed 90% in downtown this summer, making it among the hottest markets in the country. Full recovery of the local hotel market is anticipated next year and is set to even eclipse pre-pandemic occupancy levels.

In context of the mayor’s DAP, hotels are seen as a valuable use downtown since they bring visitors who have disposable income and have a propensity to spend money at nearby businesses. Hotels also visibly help with activation since there is a turnover of guests who stay throughout the week — including weekends — and most guests inevitably walk or roll on nearby streets. Thus the thinking is that hotels can help provide around-the-clock activation unlike offices.

The zoning changes in Belltown’s DMR/R 95/65 zone is pretty straightforward. A text amendment in the land use code fully exempts hotel uses from FAR limits in new structures. Hotels could reach six stories and effectively achieve a 6.0 FAR regardless of whether or not a residential component is involved in the project. That’s a big incentive over existing development regulations because the practical FAR limit for commercial uses (including hotel uses) is 1.5, translating to a limit of 1.5 stories for a commercial structure covering the entirety of a lot.

The main policy issue with the zoning change is that hotels in the area will no longer need to participate in the local incentive zoning program. That could mean fewer contributions to development of childcare and preservation of landmark structures, but it could also mean more affordable housing. Hotel projects would still be expected to contribute to the city’s MHA program.

On Tuesday, the hotel rezone was passed unanimously by the city council in a 9-0 vote.

Other zoning changes in the works

Earlier this year, the mayor was successful in getting the city council’s sign-off on major changes to the city’s industrial lands and adopting permanent higher State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) thresholds in downtown zones. Those higher SEPA thresholds exempt more downtown projects from full environmental review, which adds costs and opens more avenues for predatory delay via SEPA appeals. The industrial lands changes rezoned some areas near downtown for housing and commercial activities as well as introduced zoning bonuses for innovative and office uses in some areas. The mayor’s plans for a makers district near the stadiums, however, did not survive.

The mayor has other changes to the city’s land use code in mind, as outlined in his Downtown Activation Plan factsheet. These include extending the life of land use and building entitlements and permits, waiving or modifying development standards to encourage tower office-to-residential conversions, incentivizing childcare with extra building heights, allowing a variety of less active uses at street level (e.g., office, lab space, residential building amenities), and facilitating retail and entertainment uses at all levels of a building in downtown zones. Another idea the mayor has is to waive building code retrofits for temporary uses and reverting to past uses.

And of course the biggest reform of the bunch will be the Seattle Comprehensive Plan Major Update due in 2024. OPCD is studying five alternatives and the most ambitious of those — the Combined Alternative 5 — would make room for 120,000 additional homes over the next 20 years. Alternative 5 would add more multifamily zoning in transit corridors, allow missing middle housing (such as fourplexes) in formerly single family zones, and create denser “neighborhood anchors” around business districts where City-designated “Urban Villages” do not exist. The other alternatives would do only one of those things.

The City had originally pledged to release its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) showing its analysis of Comprehensive Plan alternatives in April, but the Harrell administration has repeatedly delayed its release. OPCD is still pledging a fall release, but an exact release date is not known and the 45-day comment period following the draft’s release overlapping with the winter holidays could cause issues scheduling outreach events.

It will ultimately be the Comp Plan update that will be the Mayor’s biggest legacy on zoning reform and housing production. The release of the Draft EIS, when it finally does happen, should offer some clues as to whether the mayor is going to support Alternative 5 or push for a lower growth alternative.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.