Strangely, it is very difficult to answer the question: “How many zones does Seattle have?” That alone suggests an uncomfortable answer.

The Seattle Municipal Code lists 38 zones. These include 10 residential zones, 5 commercial zones, 4 downtown zones, and 5 (soon to be changed) industrial zones. There are also seven flavors of Seattle Mixed zoning and some special designations for the International District, Harborfront, Pike Place Market, and Yesler Terrace.

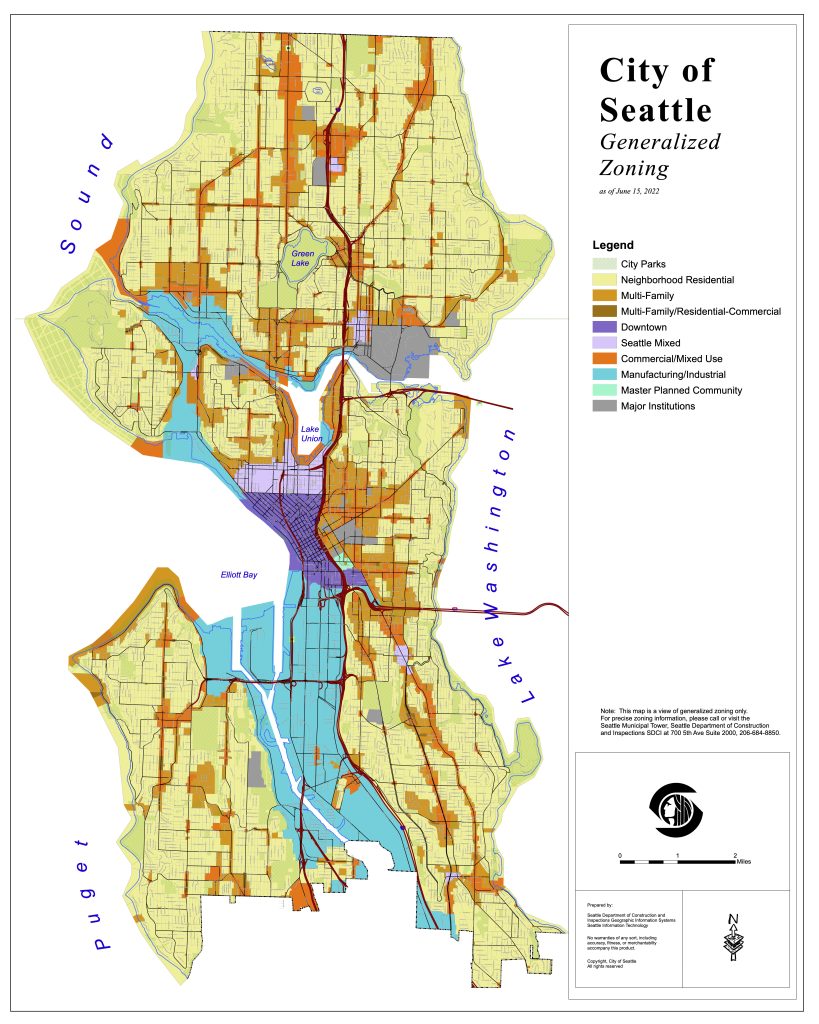

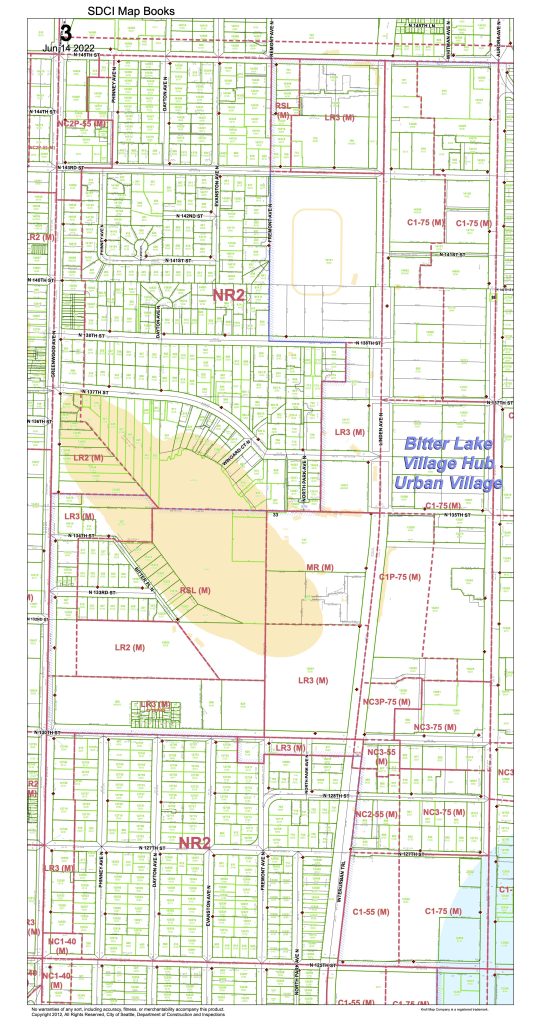

The city offers maps to describe two other, somewhat contrasting views of what is in the zoning ordinance. The Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) publishes a “color coded, birds-eye view of Seattle’s zoning” that is both easy to understand and wildly imprecise. Such imprecision is shown in the other document, or technically 204 documents they publish that comprise the official zoning map book.

[Note: I had the hardest time downloading the “simplified” map as a pdf and getting it converted to include here. That the SIMPLIFIED map is a 9MB beast and such a massive memory suck as a .pdf suggests a larger underlying issue.]

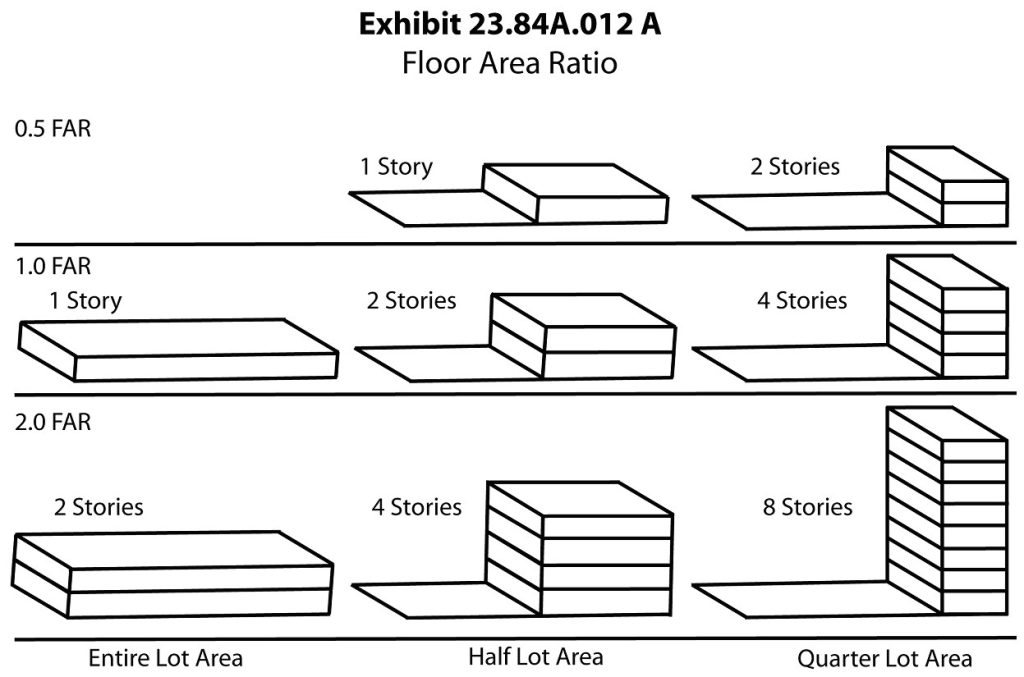

A look at the city’s official zoning maps shows that we are not dealing with the 10 steps of Low-Residential through High-Industrial zoning spectrum of SimCity. Seattle’s is not a spectrum of density, nor is it simple. Zoning designations add several other features to each basic land use call sign. There is the original zone like Commercial 1 or Neighborhood Residential 3, which is then appended with a height limit. Thus you get C1-55 zoning that limits commercial buildings to 55 feet in height.

Such basic zones can also be modified with a “P” for a Pedestrian Street, or pedestrian retail area, applied along major commercial streets to promote pedestrian-level retail. Mandatory Housing Affordability areas are designated with an “M”, “M1”, or “M2” depending on the level of developer contributions required for the area. Areas near universities or hospitals can be applied with a Major Institution Overlay (MIO) designation.

Usefully, the city’s GIS department has to map these designations. The Current Land Use Zoning Detail table shows that Seattle has 285 separate zones.

Should each of these be considered a separate zone? Ostensibly, height limits are just a cap. However, Seattle embeds land use rules within the height and pedestrian street designations. The Seattle Mixed zones changes the permitted floor area ratio with each height limit. Downtown zoning gets different green street bonuses in each height zone. Pedestrian streets have additional uses permitted (restaurants and shops) or discouraged (automobile-oriented services). Also, the code helpfully states in Chapter 23.30.010: “A zoning classification that includes a numerical or letter suffix or other combinations denotes a different zone than a zoning classification without any suffix or with additional, fewer, or different suffixes.”

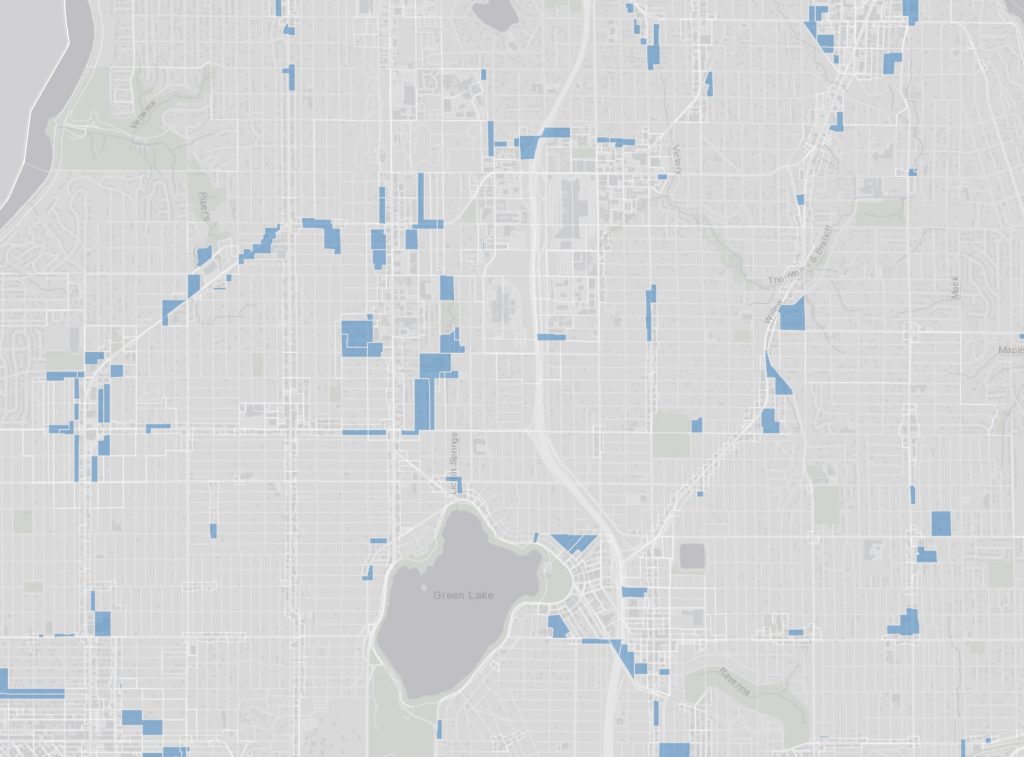

The application of Seattle’s 285 zones is difficult to wrap one’s head around, thus making simplified maps like the one above a necessity. Such a simplified map suggests there are rules with lots of exceptions. However, that’s not so much the case. Seattle’s 1,700 pages of land use rules make exceptions, one-offs, and unicorns the standard operation.

Of the 285 zones, there are 88 zones applied a single time in the city, and another 50 zones that are only applied twice. Together, these 138 zones cover just 2.2% of Seattle. The largest of these is the SM-UP 95 (M) (Seattle Mixed, Uptown) zone which covers Seattle Center and the Gates Foundation property. Close behind is the DOC1 U/450-U (Downtown Office Commercial Unlimited) zone which is the unlimited height tower zoning applied to the south end of downtown.

Which means the rest of these unicorn zones are smaller than the Seattle Center. A lot smaller, as 46 zones are each applied to less than two acres of the city in their lone use.

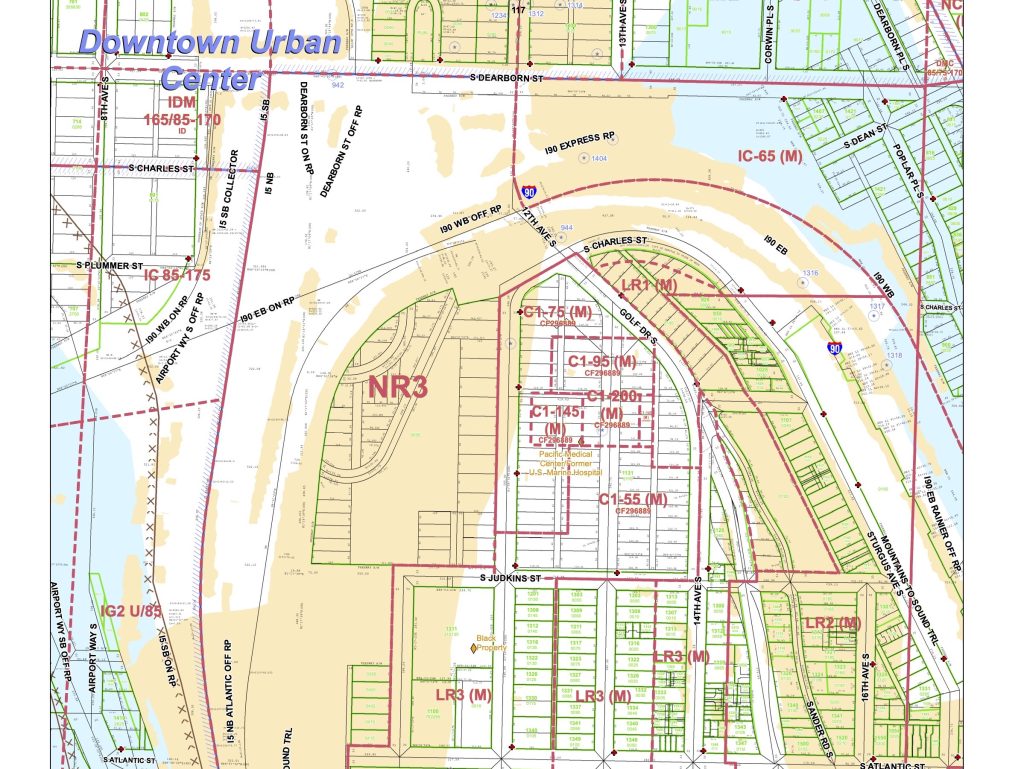

A good illustration of these single-use zones is the C1-200 (M) zone. It is used only once, on an area just less than an acre. The zone only applies to the tall part of the PacMed building atop Beacon Hill and nowhere else in town. Other parts of the same parcel are zoned C1-95 (M), another zone used only here, and C1-145 (M), a designation used only twice, on either side of the same PacMed building.

At the other end of the spectrum, LR2 (M) (Lowrise Residential 2) zoning appears the most frequently in 318 separate locations. The zoning also covers about 2.4% of the city, but does so across many bits and bobs. The two largest uses of the zone appear to be an area around Garfield High School on 23rd Avenue and E Spruce Street, as well as Sturgus Avenue underneath I-90. The rest of the applications of LR2 (M) zoning average one-tenth the size, with 114 uses being two acres or less.

Another aberration in Seattle’s zoning code is the Major Institution Overlay (MIO) zoning. Essentially, it allows for big institutional property owners to take their pick of all the other zones and apply it to their property through an agreement with the city. There are 15 such applications, like the University of Washington campus and Swedish First Hill Medical Center. MIO zoning covers 2.17% of the city’s area, but has 84 different underlying subcategories. It starts with an underlying zone, then adds a MIO-[number] that designates a height limit and applies rules that the land use must be related to the institution. Thus we end up with an absurd zoning designation like MIO-65-NC2P-75 (M) (Neighborhood Commercial 2, Pedestrian), a single-use zoning slapped on less than an acre on the corner of Jefferson and 12th Avenue.

Similarly, there are 33 separate Seattle Mixed zones applied across seven different neighborhoods like South Lake Union, University District, and Northgate. Nineteen of these SM zones are used only once or twice, the smallest being SM-NR 75 (M2) which is applied to a single parcel behind QFC on Rainier Avenue.

It’s these endpoints of the list of zones that really illustrates a basic problem in Seattle’s land use regulation. Zoning authority rests on the city’s police power “to promote health, safety, and general welfare” of the city, as the US Constitution requires and reiterated by the city code’s purpose statement. A case can be made that some layered set of tests proves that any cocktail of land uses and height limits and affordability designations does improve the general welfare of people throughout the city.

Except it fails the laugh test.

This spastic cacophony of zones undermines the zoning ordinance itself and Seattle’s competence at land use regulation because it’s absurd. The number alone, 285 separate zones, is preposterous. It shreds the trustworthiness of the the city’s ability to make a decision, just like the multitude of zones shreds the usefulness of the land it is applied to. When separate, convoluted rules apply to different sides of the same property line, and only these properties, it’s not a zoning code. It’s a farce.

Update September 29, 2023: This article was updated with information about the Pedestrian retail street designation, which was originally misidentified as “parking”.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.