With another “Future Ready” maintenance project coming down the pike in January, it raises a big question for the future: What should riders expect when Sound Transit needs to do planned or emergency maintenance work in the downtown tunnel and elsewhere in the Link system?

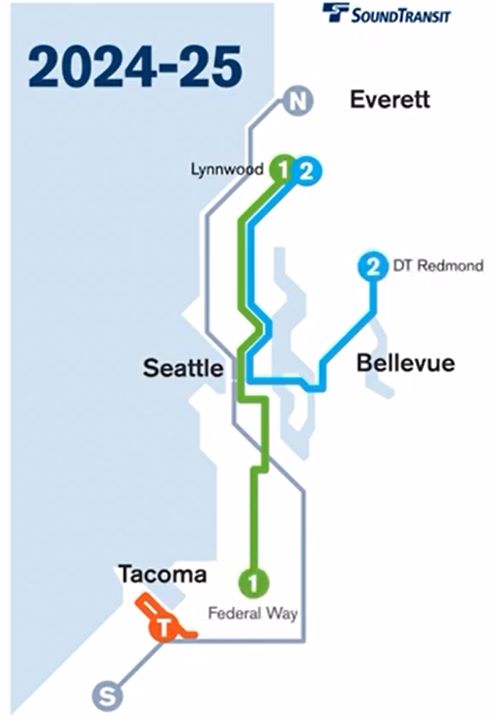

Starting in late 2025 or 2026, riders can expect the Link 1 and 2 Lines to operate through the downtown tunnel for regular service. This will effectively double the number of trains running through it, but it will also increase the complexity of operations.

With maintenance events already being a delicate matter with just one line, adding another into the mix and increasing frequency seems all but sure to gum things up. Sound Transit doesn’t have a clear cut answer to how the agency will deal with future maintenance and emergency repair projects because every situation is unique, but it’s hard to see it being any better for riders without substantial improvements to infrastructure and agency operational strategies.

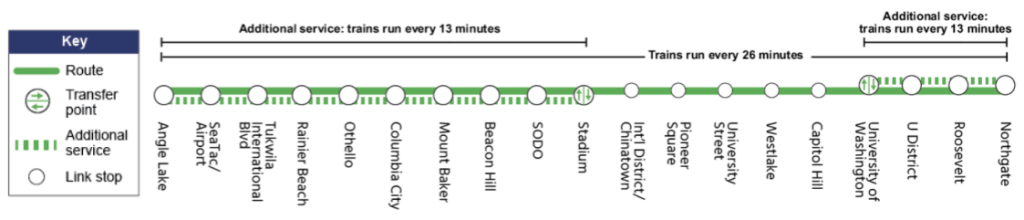

Come mid-January, Sound Transit will once again run single-tracking operations in the downtown tunnel to support critical maintenance work. Service in the tunnel will be about 26-minute intervals in each direction and extra service will be layered on portions of the system outside the tunnel to provide cumulative 13-minute frequency. On weekends, the downtown tunnel will fully close for more complex maintenance work.

It stands to reason that if the upcoming service disruption were happening in a two-line environment using the same strategy, through service in the downtown tunnel might be something closer to one 1 Line and one 2 Line trip per hour. One 2 Line trip means just one trip between Seattle and the Eastside per hour, and with low through-train options for riders to choose from, loads on trains and platforms would likely be very unbalanced and overloaded. It would be a systemwide catastrophe.

Sound Transit would probably pursue another strategy, perhaps by trying to time and platoon 1 Line and 2 Line trips together in the same direction through the downtown tunnel so as to get closer to the half-hourly frequency level. But that itself wouldn’t be easy to do and illustrates just how challenging and tenuous the tunnel could be without major changes.

To be sure, Sound Transit has made some strategic enhancements to the downtown tunnel.

Last year, the agency went through a process of sectioning the overhead catenary wire system, which provides power to light rail vehicles, into quadrants within the tunnel. Dividing the system into quadrants allows the agency to strategically turn off power to portions of the tunnel being worked on and run trains to more tunnel stations when doing so. Sound Transit previously had to be more selective about which stations could be used during a partial single-tracking event.

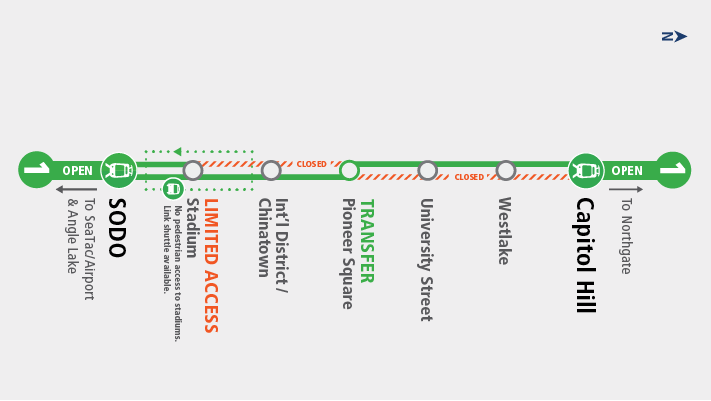

Nevertheless, the Achilles’ heel of the downtown tunnel is the inability of trains to switch tracks within it, barring a section immediately northeast of Westlake station platforms (the other nearest crossover tracks are at Stadium, Judkins Park, and University of Washington stations). That reduces Sound Transit’s ability to navigate around temporary construction zones or stalled vehicles, forcing the agency to choose from more blunt strategies. Those include using a low-frequency, blended through-service on a single-track, running a Link train as a shuttle between both ends of the downtown tunnel, or running two trains partially through the downtown tunnel to a common station with a forced transfer. All of those have their problems and seem set to be compounded when Link does get its two full lines.

A strategy that could significantly ameliorate this, however, would be installation of permanent crossover tracks (known as switches) throughout the downtown tunnel. Installing crossover tracks at the tunnel stations themselves would be the least expensive method to help trains navigate around obstacles in the tunnel. But doing so could affect service at a station where crossover tracks are in use if Sound Transit didn’t authorize a special maneuver to pull into the station’s platform, reverse the train, and then proceed forward onto and over the crossovers to switch tracks. Alternatively, the agency could select portions of the tunnel tubes between stations for crossover tracks, though that would require a more costly approach by excavating space from interior walls to lay tracks.

The addition of a second downtown transit tunnel with the Ballard Link Extension will certainly open up new options to deal with maintenance and service disruptions, carrying some of the load when the existing tunnel needs repairs. But with the specter of planning delays, Ballard Link isn’t scheduled to open until 2039 at the earliest. That means Sound Transit will need a solution for the next 15 or so years.

Another issue that Sound Transit will have to contend with is planned maintenance and unexpected service disruptions elsewhere in the Link system.

In the summer, the agency carried out several phases of maintenance work to repair sinking tracks in SoDo and replace platform tiles at Othello and Rainier Beach stations. Service impacts from the work was fairly severe with systemwide frequency reduced to every 20 minutes during track repairs and every 15 minutes during tile replacement. The agency blamed lower-than-planned frequencies on a variety of factors, including signal systems when operating on a single track in the reverse direction. Trains also had to operate on a long 1.5-mile segment of single track since crossover tracks are only located north of Othello station and south of Rainier Beach station. Clearing that whole segment takes time, especially with two station stops along the way.

Sound Transit will invariably have many substantive maintenance work and unexpected service disruptions (e.g., motorists crashing into Link trains in the Rainier Valley) that necessitate single-tracking outside the downtown tunnel. Minimizing their impacts should be a bigger priority than they have been in the past. Some key questions that policymakers and agency staff should be asking and answering, include:

- Could Sound Transit take actions that further limit the severity of single-tracking events and improve system operations through strategic infrastructure investments?

- Does a whole line have to suffer a significant loss of frequency or could the agency maintain normal frequencies outside construction and service disruption zones?

- And, can more maintenance work be shifted to late-night periods or when the system is closed to limit rider impacts?

If the scope and frequency of planned maintenance single-tracking events continues like it has with 10-day or 20-day service disruptions, it’s hard to imagine riders tolerating it like they have in the past with impacts spreading widely across a system soon to grow to 57 miles and eventually to 116 miles. That’s why Sound Transit should have to answer how the agency can and will limit severe service disruptions before the Lynnwood Link, East Link, and Federal Way Link Extensions even open, not when they’re poised to imminently happen in a post-Sound Transit 2 expansion environment.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.