Seattle is growing. How do we make room for new housing and create the kind of city we want to live in?

Seattle Mayor Harrell’s newly released Comprehensive Plan Major Update draft reflects the administration’s best take on how we should grow the city over the next 20 years, how we understand and mitigate the impacts of growth, and how we guide future investments in infrastructure, transportation, housing and climate adaptation. The central vehicle is a revised growth strategy to replace the 30-year-old vision of ‘Urban Villages.’

While the draft hits many of the right notes in the rhetoric, the growth strategy is a slippery abstract beast. Between the supporting documents such as the Housing Appendix and the Anti-Displacement Framework and the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), the City has outlined seven themes for the growth strategy. Let’s dig in to see whether this plan will meet our challenges and where we could do more.

Increase housing to ease rising rents caused by competition for limited supply.

Under Harrell’s plan, the existing Urban Villages are mostly rebranded as ‘Urban Centers’ but the zoning stays roughly the same. We can do more:

- Taller buildings in growth areas. Around our light rail investments, tall buildings should be the norm. As job centers, they should be paired with enough zoned capacity to make thousands of homes there. For example, the new 130th Street Regional Center is stated to add only 1644 homes (DEIS, page 1–77), but could be home to thousands more. And as Councilmember Morales has pointed out “…excluding the South End from intentionally planning for economic development opportunities…(will create)…deeper economic inequality.” It is the natural progression for Seattle moving from a single downtown destination to a polycentric network where you can walk to your job or take transit to another neighborhood without ever going downtown.

- Add a story elsewhere. Adding a story or two elsewhere has a marginal impact on the street, but these are the cheapest floors in any development already being built. In the rebranded Urban Centers, 30-foot-tall Residential Small Lot zoning should jump to 40-foot and 55-foot height limits. This 4–5 story scale is the baseline for nonprofit developers to build subsidized affordable housing, and also the scale at which we start to see for-profit developers provide affordable units under Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA). There may not be the political will for the 5–8 story urban streetscape of a Paris or Copenhagen, but more new development should hit that sweet spot.

- Zone for mass timber. Buildings made from mass timber, a low-carbon alternative to steel or concrete, can go up to 18 stories under the Washington State building code. We should optimize the zoning to match the building code and let the market produce green towers.

Increase diversity of housing options throughout Seattle to address exclusion so more people can live and stay in the neighborhoods they love.

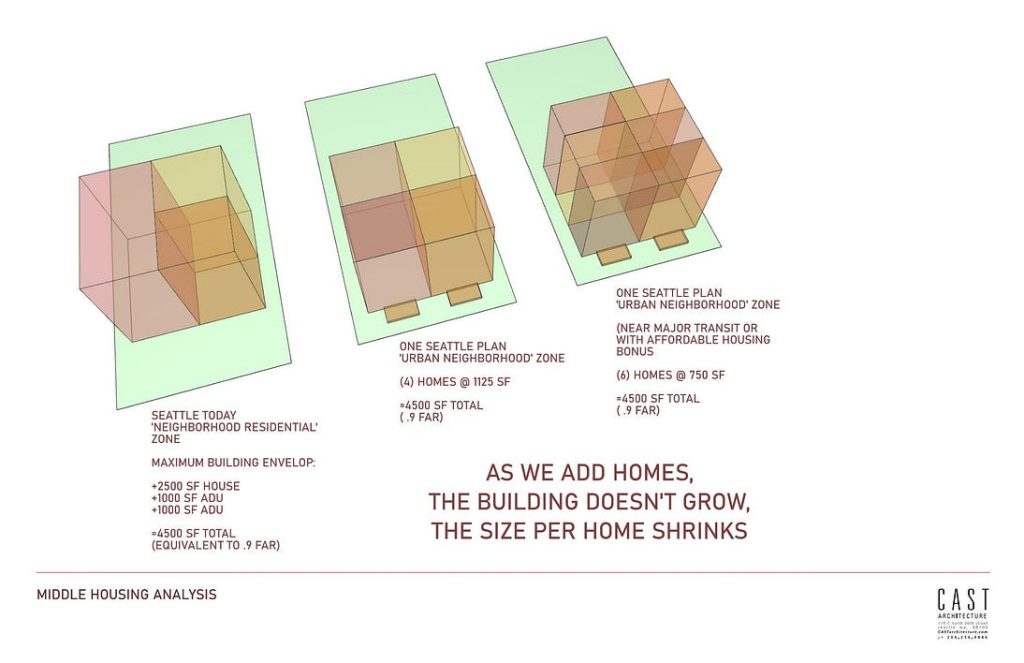

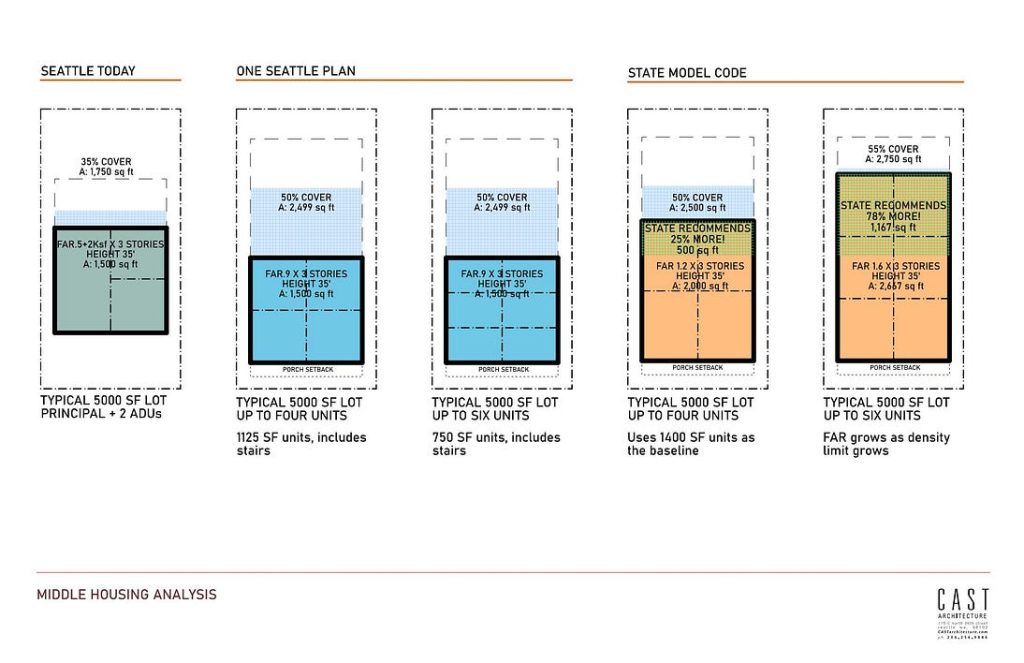

Last year, the state legislature passed HB 1110 prescribing cities replace single-family zoning with ‘middle housing’–up to four and six homes per parcel. Seattle’s approach has embraced the letter of the law, but not the spirit. Harrell’s plan increases the density from three to four or six units per state law, but doesn’t allow those buildings with more units to be any larger than what we allow today — it effectively mandates smaller homes. The Department of Commerce wrote a model code for HB 1110 that uses a sliding scale to increase allowable floor area as the unit count increases, based on 1400 square-foot unit.

There are already significant headwinds to middle housing development, and the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) has yet to show how their approach would yield considerably more units over today’s norm. Seattle should embrace middle housing with implementation that supports flexibility and the most homes. Some suggestions:

- More than townhouses. Granted, smaller homes are generally less expensive, but shorting middle housing will drive more projects into the typology we already have: three or four units on a parcel (like today’s NR and RSL zoning). There is a strong market preference for townhouses and the city’s approach will make it easier to build and sell those, but it leaves the extra capacity granted by HB1110 on the shelf unbuilt. To get the other types of middle housing, such as sixplexes, the update should factor in some bonuses for height, setbacks or floor area.

- Reward extra units The update should either allow for more bulk as you add units as an incentive like the State model code, or use a more basic unlimited density within the buildable area like Spokane’s successful Building Opportunity for Housing program.

- Don’t count ADUs when counting density. Over the last several years, accessory dwelling units (ADUs) have become popular because they have low barriers to permit and flexibility that fit many residential sites. The Update counts them against the four or six unit maximum per parcel, closing the code exceptions, like exemption from MHA, that makes them so popular (2500 ADUs in just the last three years). They are low-impact infill development and there is no reason to kneecap this housing type.

Allow more affordable rental and ownership housing types throughout Seattle

“Over the last 10 years, the average annual Zillow Home Value Index for a detached home more than doubled from $415K to $946K, far beyond what most Seattle-area households can afford. The median monthly cost of rent and basic utilities increased by 75% from $1,024 in 2011 to $1,787 in 2021.” (City of Seattle. One Seattle Plan draft plan 2024. pg 5.)

- Pay for affordable housing units for new projects under development, rather than extract fees to build them elsewhere. If we want income-restricted units to happen in small developments distributed throughout the neighborhoods, inclusionary zoning isn’t a good program to create them. Portland has a new program where the government fully funds the gap between the market rent a developer might need to make a project work financially and the reduced rent for lower-income households (affordable to people making 60% of the area median income) in the form of a tax savings. Those income-restricted units are cheaper to build because they’re part of a larger development (over 20 units).

Create more opportunities for income-restricted housing, especially permanently affordable homes

While Seattle has an enviable track record of building subsidized housing through the Office of Housing, Seattle Housing Authority, Mandatory Housing Affordability and the Housing Levy, it is not enough. Seattle would need to fund the equivalent of a billion-dollar Housing Levy every year for the next 18 years to meet the demand for affordable housing.

When we see the 80,000 new homes target in the update, more than 70% (56,581) are supposed to be income-restricted for people earning 0–80% of the area median income (AMI). This doesn’t include the additional 17,121 emergency beds needed over the next 20 years. For context, the 2023 Housing Levy will generate only 3100 new units over 7 years

- Solve for affordable housing. First, the kinds of buildings funded and built for income-restricted housing are not low-rise middle housing in residential neighborhoods — they are largely four- to eight-story mid-rises in growth areas. More urban centers need to be zoned for this scale of building. If we want affordable housing distributed throughout the city, we must repeat similar zoning in the new ‘Neighborhood Center’ place type.

- Resist the urge to expand Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) into zones we hope to build middle housing. ADUs (not subject to MHA) have exploded, up 217% over four years, versus townhouses (subject to MHA), are off 77%. Builders will go where the barriers are lowest. A recent study by Shane Phillips about inclusionary zoning in Los Angeles illustrates that for every affordable home that Los Angeles’ inclusionary zoning program created, it cost four to five market-rate homes. In the plan, OPCD studied expanding MHA into Urban Neighborhoods, but only netted three more income-restricted units built on-site there (DEIS, pg 3.8.46).

- Recalibrate the Multi-Family Tax Exemption. The most ambitious alternative only anticipates 525 new Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE) units. We found in our Spokane Six project that MFTE helped our bottom line and was something we could achieve at small scale then repeat across additional projects. In Seattle, to take advantage of this program, higher percentage of units and lower income limits, combined with current interest rates effectively wipe out any financial incentive to pursue MFTE.

Reduce residential displacement and support existing residents who are struggling to stay in their neighborhood as it grows.

The comprehensive plan’s Anti-Displacement Framework is a restatement of existing strategies. To get growth without displacement, and support low-income households:

- Align the affordable housing bonus building type with Habitat for Humanity and Seattle’s Social Housing Developer. The affordable housing bonus type (1 unit per 400 square feet of lot and a floor area ratio or FAR of 1.8) in the Updating Seattle Neighborhood Residential Zones documents might be more workable for those specialized builders if the affordability requirements mirrored their optimal pro formas. This is a natural alignment with the nascent social housing developer’s publicly supported mission and the principles of the comprehensive plan.

Address past and ongoing harms from housing discrimination, racial disparities, and exclusionary zoning

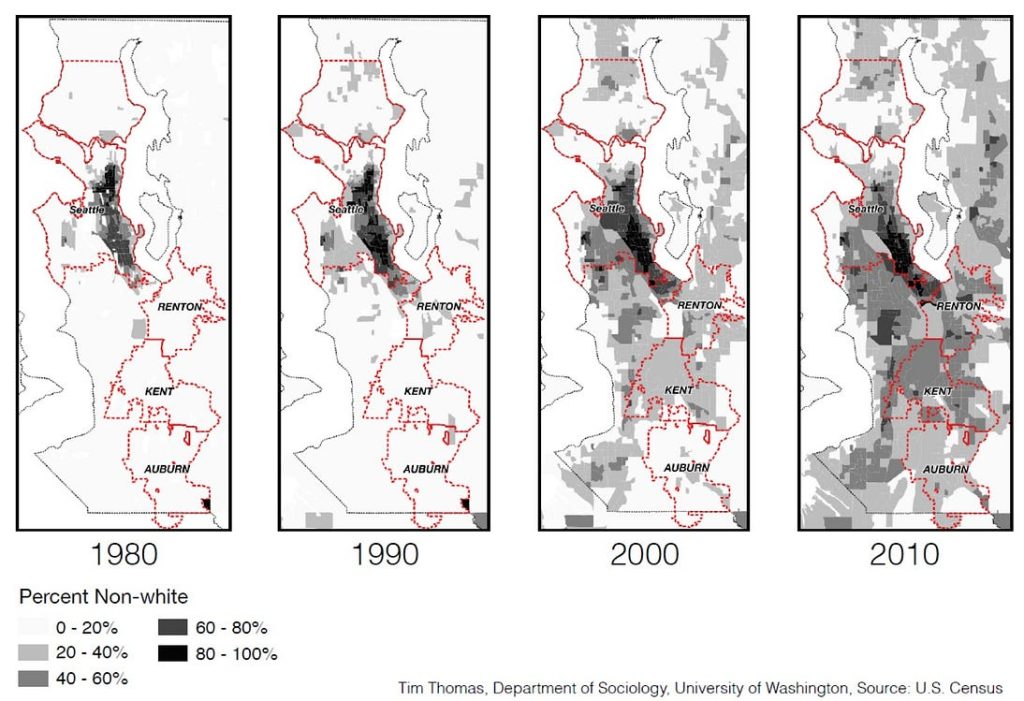

One of the core critiques of the Urban Village growth strategy is that areas targeted for growth were overlaid on the formerly redlined neighborhoods in the Rainier Valley and Central District where Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) and low-income residents had built communities despite systematic underinvestment. Thirty years of growth in these areas has already led to the displacement of the people, the cultural institutions, and the businesses they’d built. Largely, the damage has been done.

The plan is explicit about putting additional zoned capacity in high opportunity/low risk of displacement areas, but we could do more:

- Center new housing on parks and shorelines, less on arterials. The health impacts of placing multifamily housing on arterials are well documented and disproportionately affect BIPOC and low-income residents. As a means to equitably increase access to nature, light, air, and recreation, the plan should prioritize housing around parks and shores.

- Provide professional development assistance for property owners. To support Seattle’s goal of having more daycares, the city has a roster to provide feasibility studies for daycare providers to help expand their facilities or stand up new ones. In line with equitable development zoning, the city could support a pipeline of small development by helping BIPOC homeowners leverage their property and move through the development process.

Create complete neighborhoods where more people can walk, bike, or roll to everyday needs.

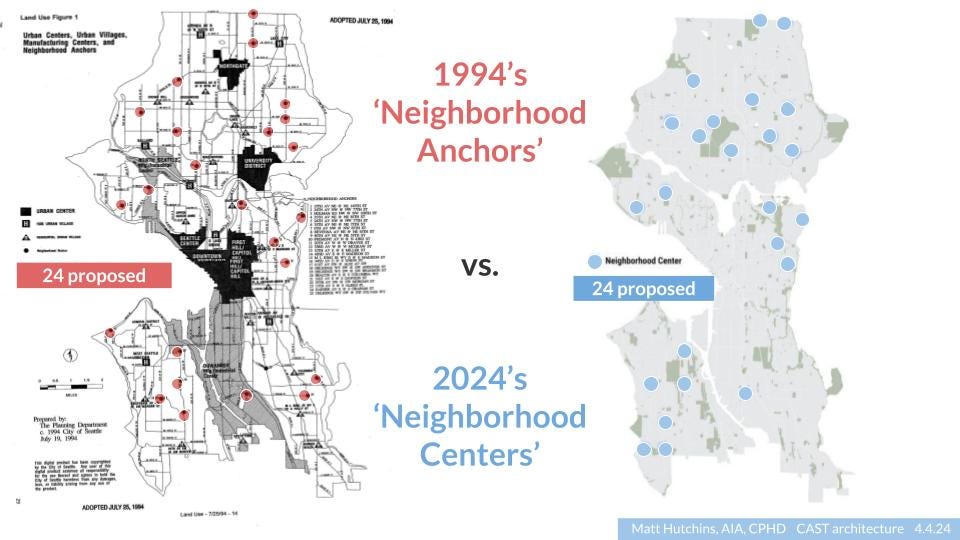

The biggest new change in mayor’s growth strategy isn’t middle housing, it is Neighborhood Centers — a new zoning place type elevating the organic small commercial nodes we find in just about every neighborhood, built before zoning. The idea itself isn’t new — a recognition of the potential of these real places where explicitly called out in Seattle’s first modern Comprehensive Plan in 1994.

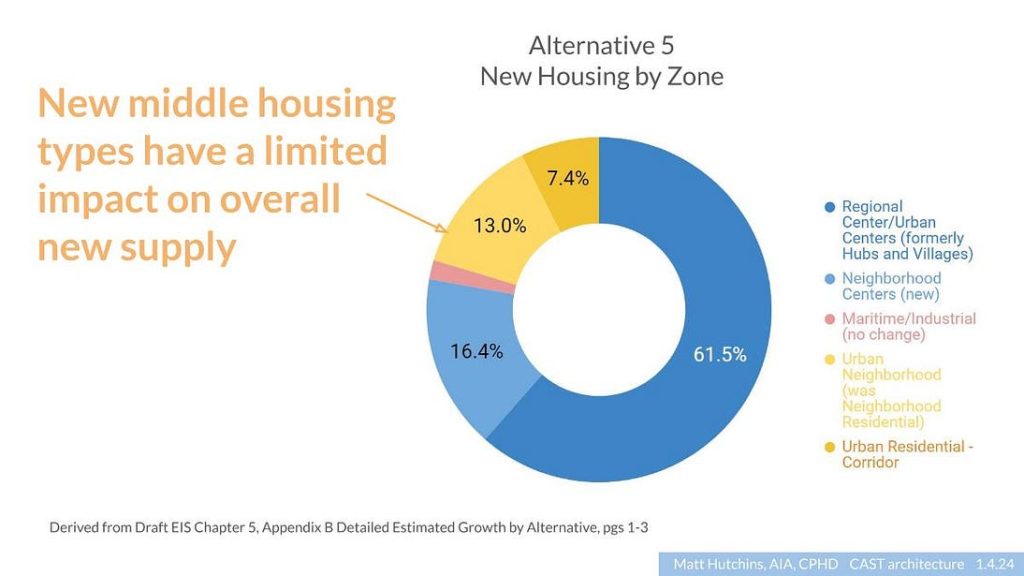

- Support Neighborhood Centers. Just because the idea has been around, doesn’t mean that it will be accepted easily. Actually the fact that zoning hasn’t changed at all around them for decades is proof of just how difficult it will be politically. Already, between the scoping report and the draft plan, the number and area of the Neighborhood Centers have been clipped, from 42 in the scoping report to 24, and from roughly 3,000 acres to somewhere around 1,000 acres. (In fact, OPCD proposed nearly 50 Neighborhood Centers in a fall working draft before Harrell officials watered down the proposal.) Yet these zones supply some of the biggest growth, nearly 20,000 units under Alternative 5.

- Embrace Neighborhood Centers as ’15-minute’ neighborhoods. They support local jobs and services, mixed use buildings, increases in the tax base and commerce, in walkable proximity both to new housing and existing neighborhoods. It is home to your favorite coffee shop or bakery, professional services like daycare, dentists, plus a library and grocery store. Every home we put into Neighborhood Centers fuels local business and keeps people out of cars.

- Build out ‘low-emission neighborhoods’ were promised in the Seattle Transportation Plan, under Executive Order 2022–07, and by both Interim Mayor Tim Burgess and Jenny Durkan. Neighborhood Centers would be perfectly suited to lowering our per capita carbon footprint.

Missing: The growth strategy as climate adaptation

There could be a more intentional acknowledgement that creating a denser city is a potent strategy for climate adaptation, especially in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Smart zoning leads to a greener city.

- Lean into infill development to reduce carbon per capita over time. Doubling density reduces CO2 emissions from residential energy use by 35% and household travel by 48%. Beyond the low-emission neighborhoods mentioned above, we should align urban design and the housing market with climate change adaption.

- Remove parking mandates (it doesn’t mean parking won’t be built). Parking requirements drive up the cost of housing, lock in carbon emissions, and require either expensive garages or extensive surface parking, taking space that could otherwise be used for vital tree canopy. In today’s Neighborhood Residential zoning, we require one parking space per principal unit. If we allow more principal units, the number of parking spaces should be based on the discretion of the developer. In 2024, there is no reason to require parking in new urban development when cities like Port Townsend, Austin, and Raleigh have already done away with this antiquated, housing-killing mandate.

- Go bigger to leverage lower carbon benefits of smart zoning. It is not surprising that the most ambitious Alternative 5 is also the greenest: 20% less electricity demand per capita, 28% reduction in natural gas demand, and a 22% reduction in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per capita.

Comment on the plan

Through May 6 at 5pm, OPCD is accepting public comment on the Comprehensive Plan via the online Engagement Hub, by email, or by attending upcoming public meetings:

- Tuesday, April 30 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm –

McClure Middle School, 1915 1st Avenue W, Seattle, WA 98119 - Thursday, May 2 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm

Virtual Online Meeting, link to be provided at a future date

This crosspost was adapted from Matt Hutchin’s personal blog, where it first appeared.

Matt Hutchins

Matt Hutchins is an advocate for housing abundance, smart growth and sustainable architecture. As a Principal at CAST Architecture, he is working on innovative housing options, from cottages to co-housing.