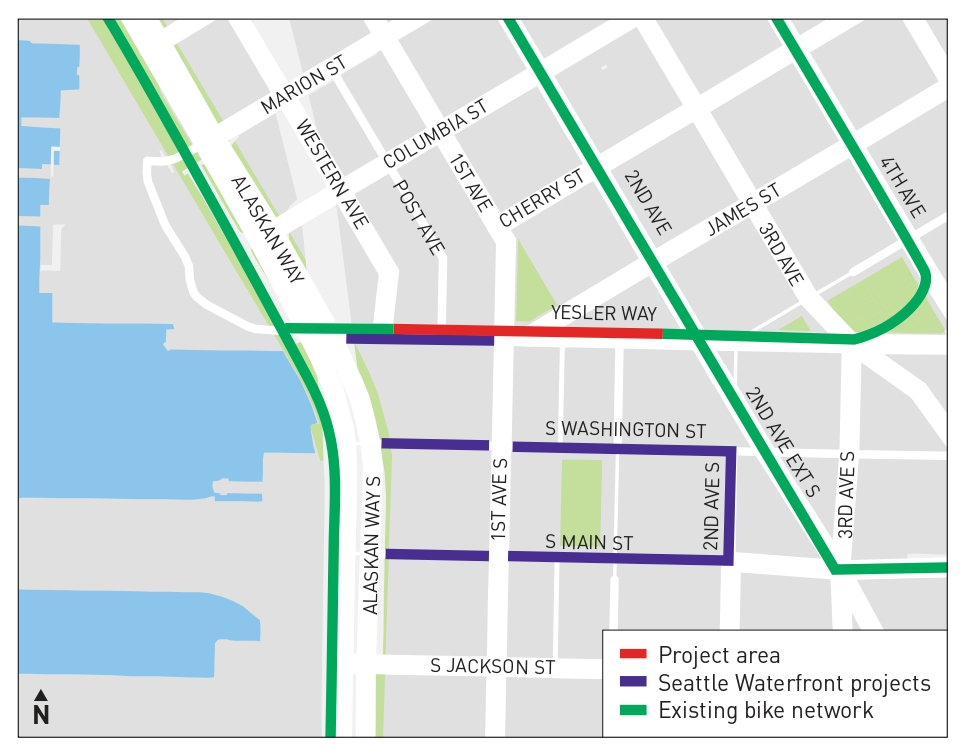

Work to fill a glaring two-block gap in Seattle’s downtown bike network has been indefinitely delayed, a decision that threatens to leave the city without a protected connection from downtown to the newly renovated central waterfront as it celebrates its grand reopening this summer. Construction on the short two-way protected bike lane along Yesler Way had been scheduled to start this spring, but The Urbanist confirmed in late June that the City has tabled the project and is reassessing it.

Bridging the gap was not originally part of the $803 million waterfront revamp, despite the clear potential to connect South Downtown to the newly opened bicycle path along Alaskan Way, which will ultimately provide a fully separated path from the West Seattle Bridge all the way to Interbay.

Waterfront Seattle project materials from a decade ago instead envisioned cyclists winding their way through Pioneer Square to access Alaskan Way. But safe streets advocates pushed for the obvious gap on Yesler to to be filled, and the project was able to move forward into design last year.

Bike advocates chalked it up as a victory in their quest to improve bike connections to South Seattle, which have long been neglected despite being among the worst hotspots for deadly crashes. The route would offer a safer path between the Rainier Valley and the waterfront — though other gaps remain to the southeast.

A major sticking point has been the City’s inability to identify funding to replace an outdated traffic signal at First Avenue and Yesler Way, right in the middle of the gap. Without a new signal, safely separating the movements of people biking along a two-way facility from turning drivers becomes more complicated. The workaround developed by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) was to build the connection, but fully restrict turns across the bike lane.

The resulting change in traffic patterns did cause some consternation at the Pioneer Square Preservation Board, which needed to approve the project, but a certificate of approval was ultimately issued last September.

Despite being given the green light, SDOT is going back to the drawing board, in the hopes of being able to secure funding to upgrade the signal, which apparently still remains a sore spot.

“This project is moving forward, but we’re exploring using FIFA-related funding to make changes to the signal at 1st & Yesler first. Signal changes could benefit the protected bike lane (PBL) project as it would not require new turn restrictions and also improve safety for pedestrians,” SDOT spokesperson Amy Abdelsayed told The Urbanist. “Should the signal project be feasible it would be constructed in advance of the PBL. As signal design proceeds, we will have a better information on construction timeframe.”

Replacing the outdated signal, which doesn’t include any pedestrian signals, much less accessible crossing infrastructure for blind or low-vision residents, would be a step forward, but why not come back and install a new signal after building the bike lane connection?

“We’ve heard concerns about the turning restrictions that would be introduced by the project, especially so soon after major changes to street directionality and turn access,” Abdelsayed said. “To provide the best version of the project possible we have elected to phase it so that work is done at close to the same time.”

Earlier this year, a likely delay on the project attracted the attention of Cascade Bicycle Club, with Executive Director Lee Lambert sending a letter to the city urging that the project move forward. That letter cited the 2026 FIFA Men’s World Cup as the date that the City should treat as a red line.

“The Yesler Way protected bike lane (PBL) is fully funded, shovel-ready, and must move forward without delay,” Lambert wrote. “Completing this project by summer 2026, before the FIFA World Cup, is essential. Seattle’s bike network has faced setbacks in the past due to postponed projects, and we cannot afford delays in delivering the safe bicycle infrastructure Seattle has invested in and needs. As Seattle moves forward with the Keep Seattle Moving Levy and the Bicycle Safety Program, the Yesler Way PBL exemplifies how small, strategic investments can close critical network gaps. Completing this project without disruption maintains the momentum for a connected, safe, and accessible bike network.

Updating the signal means going back to the Pioneer Square Preservation Board, a group with a history of subjecting projects to arbitrary delays and requests that stray far beyond the mandate that it has to ensure consistency with the neighborhood’s historic character.

“Changes to the signal equipment will most likely require taking the project back to the Pioneer Square Preservation Board,” Abdelsayed said. “At the meetings last year, the board had very few issues with the project from a preservation perspective but were also concerned by the turning restriction at 1st and Yesler.”

The timing remains up in the air. “For a timeline we don’t have much of a rough idea beyond the necessity to finish the project before the World Cup due to the event mitigation funding used to expand the project,” Abdelsayed said.

Cutting the ribbon on the new waterfront with the Yesler connection unfinished would be a stark illustration of the lack of broader network planning that went into the waterfront project. It clearly should have been a part of waterfront planning from the very beginning, and that lack of planning continues to impact residents and visitors just trying to get around downtown safely.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.