There are signs that Seattle could be headed toward a place where the future of your neighborhood, from traffic safety upgrades to future housing growth, may depend on who your district councilmember is.

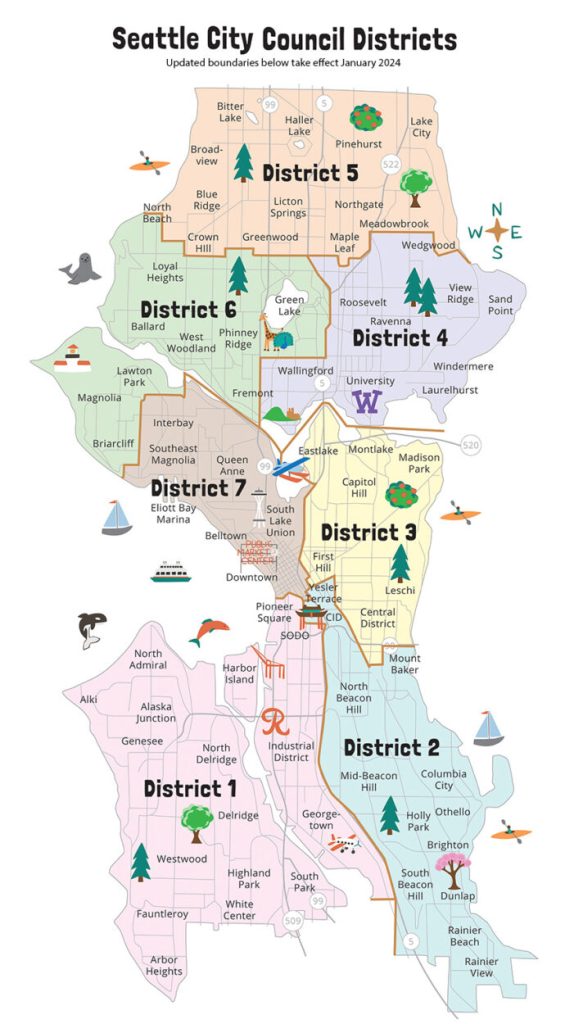

In a departure from past practice, a new dynamic has been developing since Seattle’s 2023 council elections in which the voices of the seven district councilmembers are elevated up over their colleagues when it comes to issues within district borders. This is happening across multiple areas, including human services and transportation, and could play a major role in upcoming votes on amendments to the One Seattle Comprehensive Plan.

In many large U.S. cities, councilmembers elected by geographic wards or districts are often afforded special deference. In Chicago, this is called “aldermanic privilege” and has repeatedly come under fire for creating small fiefdoms, inviting cronyism, and making it harder to implement citywide programs.

Seattle mostly avoided creating this type of culture in local government, in large part by electing its councilmembers on a citywide basis for over 100 years. The at-large era didn’t mean that councilmembers were never able to advocate for the neighborhoods they know well or earmark funds for special projects, but there wasn’t a baked-in assumption that the authority of one member to make decisions impacting a geographic area should be respected above their colleagues.

That looks to be changing. The seven-district system has been in place for nearly a decade, with the first round of district councilmembers elected in 2015. However, the current council has been explicit about seeking to creating something new, and have taken things to the next level. In their deliberations, councilmembers have increasingly highlighted which district a particular project is located, with at-large councilmembers often glided over in those conversations.

Councilmember Rob Saka, who represents District 1 (West Seattle, South Park, Georgetown) and chairs the transportation committee, has been more explicit about this new era than some of his colleagues. He intimated that councilmembers should be granted more influence over Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) projects within their district.

“We now have seven elected district councilmembers,” Saka said during a committee meeting this past March. “As elected officials in our respective districts, we are more connected now more than ever to our various neighborhoods and communities. With that tight integration and connection, comes closer direct engagement with city departments, including critically important ones like SDOT.”

Saka is the second councilmember to represent District 1 on the council, after Lisa Herbold was elected in 2015 and reelected four years later. Herbold declined to run for a third term in 2023.

Saka’s speech came as the committee was reviewing SDOT’s 2025 work plan for the city’s new transportation levy, and the department had been meeting with councilmembers one-on-one to discuss what should be on the list. After those meetings, two sets of projects were added to the workplan, according to SDOT — one in Saka’s District 1 and one in Dan Strauss’s District 6.

A few months earlier, Saka had spelled out his theory as to how exactly the district council system had changed when he the rest of the 2023 council class took office.

“The OGs, who were once [elected] citywide, inherited that and then moved to a district, and they were elected on a district-based system, but they were still legacy holdovers of the citywide system, and they also retained the power of incumbency when they ran for reelection. This is the first time, with two-thirds new councilmembers, where we are all starting out fresh. The newly electeds in 2023, starting out fresh, were elected purely under the district-based system,” Saka said during a presentation on the city’s Safe Routes to Schools program in January. “It’s a fundamental shift in dynamics.”

The meaning behind the message was clear: City departments should be more responsive to the district councilmembers.

“It’s kind of a reckoning that many executive departments are having this this past year, with how to best communicate and engage with this fundamental shift in dynamics of this council,” Saka said.

Last week, things took an even more explicit step, with the council’s transportation committee discussing how to implement a new “district project fund” approved with last year’s city budget. Under the program, each district councilmember would be in control of a $1 million fund for both 2025 and 2026, a pot of money that would roll over into the next year if left unspent. Saka put forward the program along with Strauss, who chairs the council’s budget committee. As the program has been described to date, the city’s two citywide representatives — currently Sara Nelson and Alexis Mercedes Rinck — would only be able to provide input into how this fund is utilized if they coordinate with one of their colleagues.

The program marks the first time in the city’s modern history where a special pot of money has been set aside for a specific group of councilmembers to utilize, even before any projects have been identified for funding. Tuesday morning’s discussion was the first time this year that the council had discussed how to implement such a program. It comes on the heels of a city oversight committee for the newly approved eight-year transportation levy, with seven seats set aside for representatives of the seven districts, and the at-large councilmembers left out of that conversation as well.

“The idea is that individual councilmembers would be able to propose on their own — well, on behalf of their constituents — a number of project possibilities to be funded and and delivered under this new program,” Saka said. Saka made it clear that he sees the district fund as just one avenue for district councilmembers to be able to move projects forward that they view as a priority. “I’ve also asked SDOT to curate and provide a list of curated projects within individual council districts that would would otherwise go unfunded or unbuilt under the executive department’s current prioritization framework, including those set forth as approved in our Seattle Transportation Plan last year.”

District 7 Councilmember Bob Kettle, also calling the district council system “new,” framed the new program as a way for his office to fund priorities raised by groups like the Queen Anne Community Council and the Magnolia Community Council. This hints at a return to an earlier era where those groups were given a bigger seat at the table when it comes to selective transportation upgrades, under the District Neighborhood Council system that was disbanded under Mayor Ed Murray. Listening to a vocal community group over utilizing data to scope what areas have the highest needs raises clear equity concerns, and cuts across reforms that have been made within SDOT in recent years.

“I appreciate the opportunity to basically make transportation improvements, along the lines of Vision Zero, Safe Routes to School kind of pieces,” Kettle said. “We have our District 7 neighborhood council. We’ve gone out once on transportation pieces, and we’ll go out again to get an updated list.”

SDOT staff detailing the district fund were explicit in the fact that a district council fund would likely be used to prioritize projects that otherwise wouldn’t be eligible for funding. This raises obvious questions: how will councilmembers pick their pet projects, and what will go unfunded under that system?

“Our hope and intent for the district project fund is that, one, it would allow you to address some of those priorities that may not make it to the top of the list through SDOT regular prioritization criteria, just because the scale of the need citywide is so great,” SDOT’s Meghan Shepard told the committee.

Even without a separate fund, district deference looks to be playing a bigger and bigger role during budget deliberations. Last year, Saka famously pushed for the 2025 budget to include $2 million to make changes to the design of the RapidRide H Line project along Delridge Way, including removing a median curb that earned his ire. Budget Chair Strauss expressed potential concerns with the proposal, but nonetheless included it in a balancing package because, he stated, it was Saka’s priority for his district.

“As I said before, D6 is not going to tell D1 what to do, and I’m also going to remove myself from the conversation,” Strauss said in abstaining on Saka’s amendment, after former Councilmember Tammy Morales had requested a full discussion and vote on the issue. Morales explicitly cited concerns that the change would have a negative impact on safety along Delridge.

Saka was also successful in getting funds allocated to make changes to the on-street parking configuration in the Alki neighborhood, adjusting back-angle parking to parallel parking in the hopes of addressing negative behavior on the street. It’s unclear if this would have been a major priority for SDOT in District 1 without that budget amendment, which was approved with minimal deliberation. The amendment also included language directing the department to add parking along another stretch of Alki Avenue, a proposal that ultimately was cancelled after initial outreach showed it to be extremely unpopular.

While this shift has been most visible so far in the area of transportation, it’s occurring in other areas, too. Earlier this year, the city’s Human Services Department (HSD) announced that it was moving to a district-based model for homelessness outreach services, a change made after advocacy by District 5 Councilmember Cathy Moore, who resigned her seat earlier this month. That came before Moore directed HSD to award a contract to a specific service provider, a move PubliCola called “highly unusual.”

This fall, the council will vote on amendments to Mayor Bruce Harrell’s One Seattle Comprehensive Plan, tweaking the biggest adjustments to the city’s growth center boundaries in decades. Those amendments are set to be released on August 1. District councilmembers are likely to pull considerable weight with their colleagues when it comes to zoning within those districts, but the decisions made during those deliberations will impact housing supply and affordability across the entire city.

Automatically deferring to the respective district councilmember can also cheapen the debate. It’s often hard for the public to recognize the line between a councilmember convincing their colleagues and deference simply for deference’s sake. Especially when that deference is manifested by silence from other councilmembers.

While the district privilege era might not have fully arrived in Seattle, residents might not be able to recognize its arrival until it’s too late.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.