Eight years after signing onto an ambitious climate pledge, Seattle is getting a little bit closer to rolling out neighborhood-scale interventions intended to reduce pollution levels and make it easier to get around without a car. While exact concepts and potential changes remain at a very high level, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has narrowed down a list of neighborhoods that are in the running for the city’s first pilot program of “low pollution neighborhoods” intended to be in place by 2028.

This commitment, which was solidified in an executive order issued by Mayor Bruce Harrell in 2022 targeting transportation emissions, builds on a 2017 pledge made by 12 city leaders from around the world to create a “major area” within their borders that is free of carbon emissions by the end of this decade. It was an interim mayor, Tim Burgess, who made that pledge along with the leaders of cities like London, Paris, Copenhagen, Vancouver, and Mexico City. Burgess now serves as one of Harrell’s deputy mayors.

In contrast with many other pledge-taking cities, moves in Seattle to implement an emission-free zone have been mired in planning for years. The idea languished under Mayor Jenny Durkan, who briefly flirted with downtown road congestion pricing before abandoning the proposal and retreating to a vaguer grab bag of climate ideas that included emission-free zones.

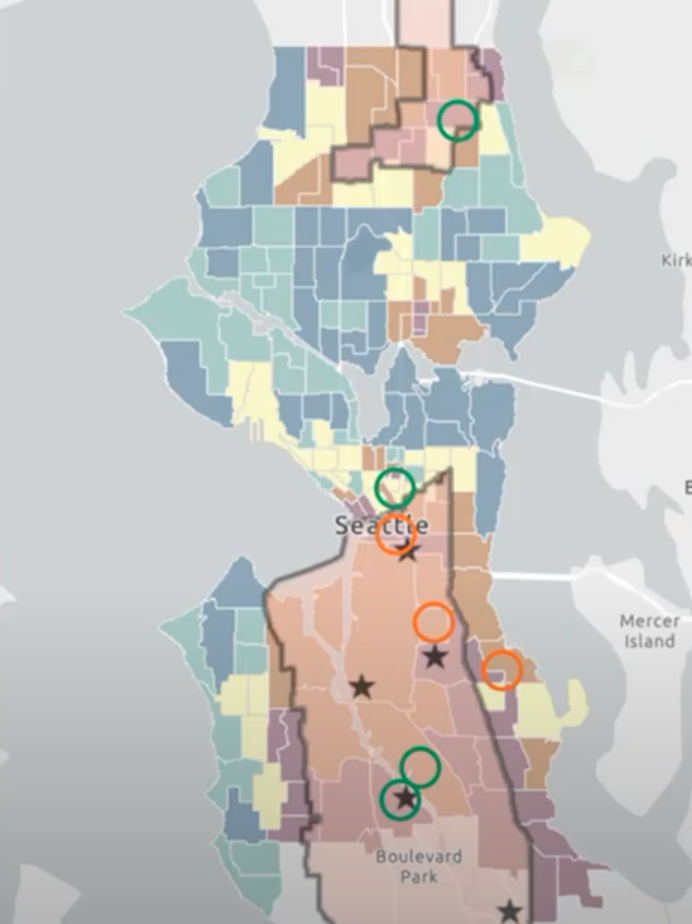

Following the receipt of a $1.2 million federal grant in 2023, along with $8 million direct funding in Seattle’s new transportation levy, SDOT is set to hire a consultant to bring the low-pollution neighborhood program into the implementation phase. Last week, Radcliffe Dacanay, the department’s Chief Climate Officer, briefed the Seattle Planning Commission on the status of the program, showing a map of potential neighborhoods that will ultimately get whittled down to three. Included were Lake City, Capitol Hill/First Hill, Little Saigon/Yesler Terrace, Beacon Hill, Columbia City, Georgetown, and South Park.

“Our first pilots need to be where LPNs make the biggest impact,” Dacanay told the commission. “We have limited funds, limited time, and that means focusing on neighborhoods, vulnerable communities guided by the racial and social equity index. These are places that are hit hardest by pollution and climate events. So we are also prioritizing areas of high crash rates and neighborhoods of high transit dependence, low car ownership, because those are the places where better walking, biking and transit infrastructure will probably have the strongest impact.”

When implemented around the world, a low-pollution neighborhood is usually an area where direct through traffic is either eliminated or heavily discouraged. Barcelona’s famous superblocks, where a section of the street grid is fully pedestrianized, with motor vehicle traffic only allowed on the periphery, is a clear example of a low-pollution neighborhood. In London, low-traffic neighborhoods (LTNs) have been deployed citywide, adding modal filters that let bicycle and pedestrian traffic through while rerouting drivers. London’s city leaders have also created an ultra-low-emissions zone in the city’s central core, charging vehicles that do not meet a certain emissions standard for entry.

What Seattle’s low-pollution neighborhoods would look like remains murky and to be determined. SDOT’s presentation to the planning commission mentioned street plazas, closed event streets, streateries, raised crosswalks, electric vehicle charging infrastructure, and more street trees as potential street upgrades bringing about this vision. But it’s clear that SDOT will be taking a neighborhood-by-neighborhood approach to how exactly an LPN will take shape. While that comes with the benefit of getting more community buy-in before implementation, it also could mean that some neighborhoods get more effective pollution reduction treatments than others.

“Our approach to low-pollution neighborhoods is really about creating a toolkit and service delivery model that meets communities where they are and builds on what people have already known about their neighborhoods,” said Jaya Eyzaguirre, SDOT’s Low Pollution Neighborhoods Senior Urban Designer. “The goal is straightforward. We want to improve air quality, climate resilience, mobility, safety and community health, and we’re keeping our focus pretty sharp, prioritizing safety as a public health issue through Vision Zero, while also ensuring that our climate response delivers real equity outcomes.”

The SDOT team overseeing the program made it clear that the lack of specificity is a conscious choice at this phase.

“One of the things we really tried to do is not put out what a low-pollution neighborhood looks like,” Dacanay said. “Because oftentimes when we talk about this, the examples we get are European. And when we first started talking about this, a lot of folks were like, ‘Well, our neighborhoods aren’t like that, and we’re not going to achieve that level.’ There are some neighborhoods that could meet some of those European ideal ways, and for those neighborhoods, great, and those are some measures that we might use.”

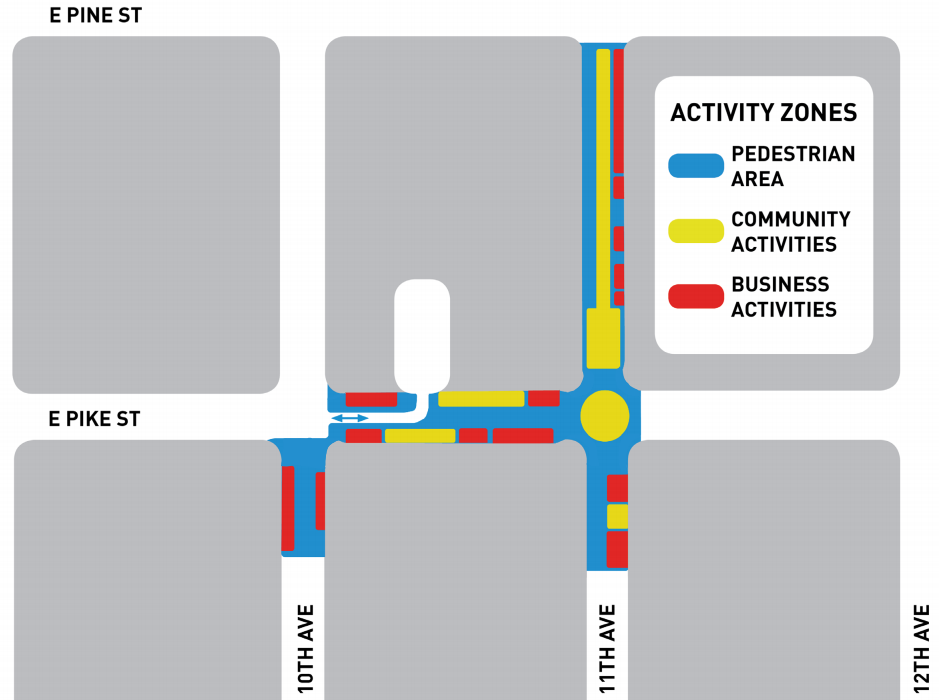

Capitol Hill was specifically cited as a place where “European style” street treatments could be implemented — despite a track record of failing to get traction for such programs in the neighborhood or from city hall. From 2016 to 2018, SDOT piloted a “people street” along E Pike Street, closing different portions of the corridor between Broadway and 12th Avenue and testing out different ways to activate them. The pilot remained very limited, and ultimately fizzled out.

Then in 2022, Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda revived hopes of a potential Capitol Hill superblock, convening stakeholders for a walking tour to discuss the concept. That kicked up a swift backlash from business owners in the neighborhood concerned about losing vehicle access.

“A measure that works well for that particular area, but say, in different parts of the city, in other neighborhoods that might not apply,” Dacanay said. “So, I think we wanted to hold off in setting what these measures and metrics are until we had the conversation with the communities and figured out what is the highest priority for those neighborhoods.”

Meanwhile, Dacanay faced numerous planning commissioners pressing for the program to move faster on implementing treatments to decrease pollution and emissions and increase walkability and neighborhood vitality. The commission has been a strong supporter of the “Neighborhood Center” concept in Harrell’s proposed growth plan — areas of focused business activity and housing density that would make natural fits for low-pollution neighborhood treatment down the line.

“We’re facing a climate crisis. We have decades of community planning work that has happened across the city that could be built upon and acted upon very quickly,” commissioner McCaela Daffern said. “These efforts are going to be challenging, and some people are not going to like them. And my experience has been that the City folds when there’s pressure, particularly from those who are more powerful in the neighborhoods, to say, ‘This is not working for me,’ without factoring in who it was working really well for.”

Another commissioner noted that potential changes to traffic patterns hadn’t really been discussed in the presentation and urged the city to put those benefits front-and-center.

“Hearing the presentation, the thing that didn’t stand out — there was a lot of talk about community process and trees, but what wasn’t there was: how are we going to eliminate cars?” commissioner Matt Hutchins said. “I feel you’re kind of soft selling [that] the core benefit of the low-pollution neighborhoods is a reduction of internal combustion engines. So, I’m looking for more bold action. I’m looking for it sooner. I’m looking for the pilots to be deployed, not just talked about.”

With a consultant on board, SDOT hopes to start rolling out an initial “first set of deliverables” early next year… even as it still remains unclear what exactly will be rolling out. As the recent successful pedestrianization of Pike Place through the Market shows, Seattleites are clearly clamoring for more people-centric spaces that allow them to enjoy their neighborhoods, but the test will be whether these neighborhood-scale treatments can be sustained over the long term.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.