When voters across Puget Sound hovered a pen above their ballots in the fall of 2016, considering the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) ballot measure, they were taking a leap of faith by filling in the bubble next to yes. Only a few months before, Sound Transit had finally delivered light rail to the University of Washington, a promise that the agency had been making since it first went to the voters in 1996. Light rail had only been running between Downtown Seattle and SeaTac airport for six years, and most of the promises of the 2008 Sound Transit 2 ballot measure were still undelivered: light rail across I-90, up to Lynnwood, and down to Federal Way.

With most of those planned light rail extensions focused on expanding the network into suburbs, many voters in Seattle saw ST3 as the next step for the city’s own transportation system. The funding package would finally make good on the failed promise of the Seattle Monorail Authority — which had collapsed a decade earlier after building nothing — and connect West Seattle and Ballard with trains that don’t get stuck in traffic.

A vote to approve ST3 was a vote to make up for lost decades of progress when it came to how Seattle residents can get around their city.

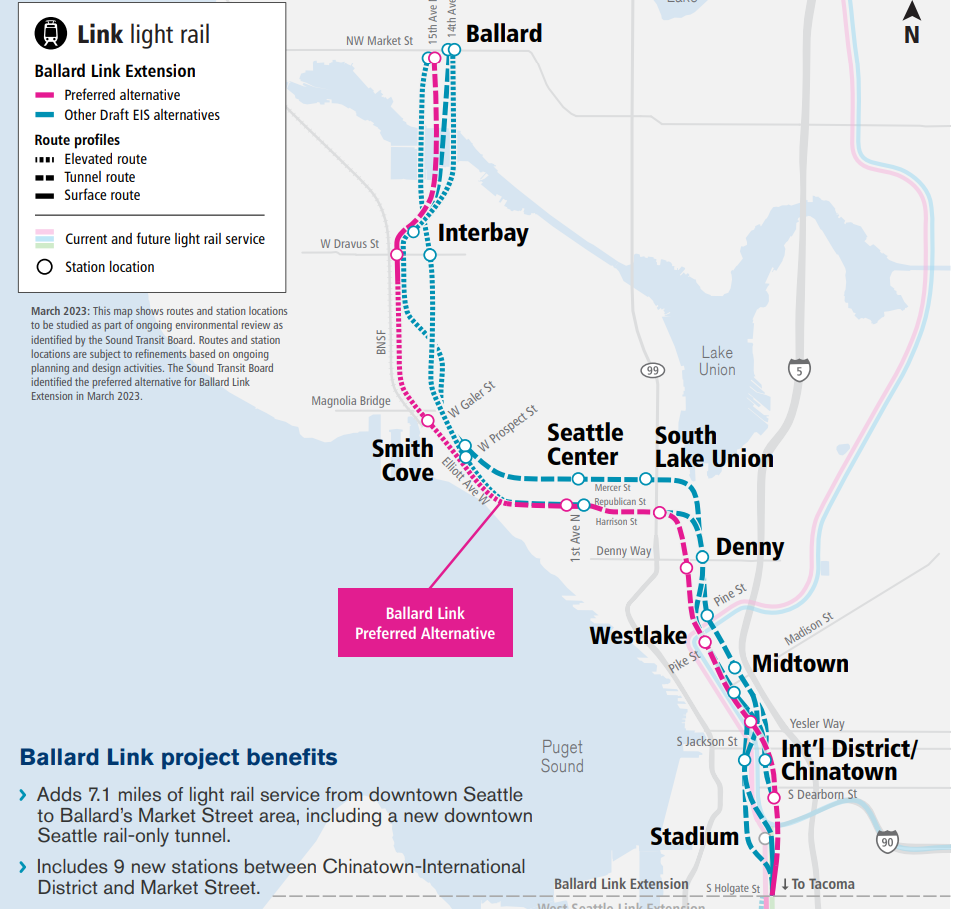

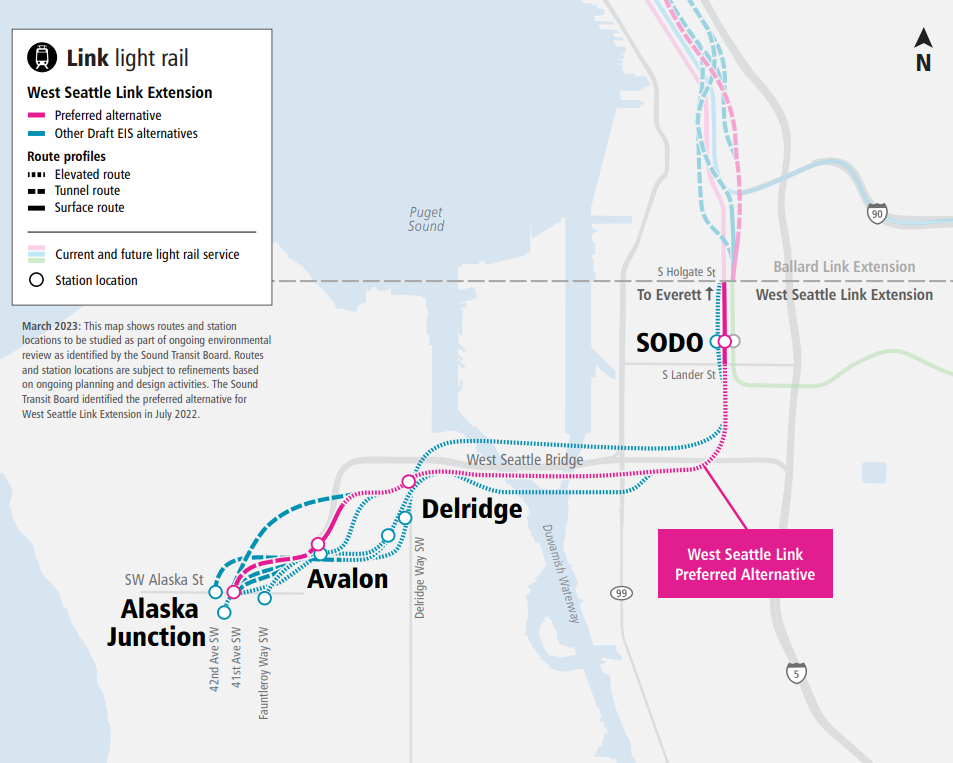

Nine years later, Sound Transit’s critics have ammunition on their side, even as Sound Transit’s current network continues to draw the kind of ridership that makes other elected leaders elsewhere in the U.S. jealous. None of the major ST3 rail projects are even close to starting construction, and this summer Sound Transit announced that the cost of building light rail to West Seattle and Ballard had gone from a $7.1 billion project in 2016 to a $30.5 billion one today. By the time both lines are built, the agency expects to spend as much as $42.5 billion after keeping up with inflation.

Despite initial promises to use bonding to accelerate project timelines and build West Seattle Link by 2030 and Ballard Link by 2035, those completion dates have slipped considerably. West Seattle Link’s on-paper completion date of 2032 risks being pushed farther back into the future yet again by Sound Transit’s financial reset, as does Ballard Link’s revised 2039 date.

So how did we get here, where two light rail projects that two-thirds of Seattle residents say they want to accelerate remain so far from actually serving riders?

Putting the ST3 cart before the horse

When voters said yes to moving forward with Sound Transit 3, the $54 billion price tag wasn’t exactly a mirage, but it was close to one. Sound Transit’s cost estimates came from looking at other transit projects from around the country, comparing the length of the alignment, the number of stations, and a number of other factors that were not directly tied to conditions on the ground where lines were planned.

“When we began looking at ST3 back in 2016, as you can imagine, there was no design development at that point in time, a very high level of estimating was used, based on, what probably was a very kind of simplistic view of the alignment, not knowing field conditions, site conditions, all those things,” Terri Mestas, Sound Transit’s Deputy CEO for Megaproject Delivery, told The Urbanist. “So a very high-level cost was derived.”

The idea of going to the voters before developing detailed cost estimates, much less starting to acquire the property that you’ll need to build a transit line is common across the U.S. In Austin, Texas, voters approved 28 miles of light rail in 2020 as part of the Project Connect ballot package, which also included bus service upgrades. Two years later, Austin Transit Partnership updated the cost estimates for those rail projects from $5.8 billion to $10.3 billion, dramatically slashing the length of the planned lines the next year.

“It’s not a good way to do planning,” Eric Goldwyn, an Assistant Professor in the Transportation and Land-Use program at the NYU Marron Institute, told The Urbanist. “You should not put before the voters a number and an alignment with any expectation that those two things are going to be the final product, because geotechnical issues emerge, property issues emerge, sensitive area issues emerge, that all change the calculus of what we end up building. So I personally would like to see more emphasis on planning earlier on, not going to the voters to get the whole thing funded and then allow for all the planning work to happen.”

Sound Transit continued to use those high-level cost estimates through the 2021 realignment Sound Transit was forced to reckon with in the wake of Covid’s impact on its finances. When Mestas came on board in early 2024 — taking a newly created position that was a direct recommendation from the agency’s Technical Advisory Group (TAG) — the capital team started to work toward develop estimates that were more tied to the reality on the ground, i.e. “bottom-up” estimates.

“Moving over to 2025, projects that are at about 10% design, which I’ll say is still very early in the design process, but we have been able to mature the designs enough that we can do bottoms-up estimating,” Mestas said. “One of the things that I impressed upon the team when I got here is we need to learn more about our sites earlier. We cannot wait until we get through the environmental process. So we have been taking more strides to do as much testing as allowable during this particular phase.”

King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci, who has served on the Sound Transit board since 2010, sees a real need for reform when it comes to producing initial cost estimates that the agency uses to plan.

“We absolutely have to get to a place where our projections are well founded,” Balducci said. “And yes, projections are projections, inflation changes, the world changes. But if our unit-cost method of figuring out how many miles of concrete and track we’re going to need, and therefore what is our big picture best conceptual budget estimate, if that is all off, then we’re setting ourselves up for failure from the get go.”

Years of dithering meet a perfect storm of cost increases

As soon as the election night parties were swept up, with voters signing off on cost estimates that were essentially guesstimates, the clock was ticking on advancing West Seattle and Ballard further in design. But despite assurances from leaders like Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan that preferred alternatives would be selected as soon as possible to expedite environmental review, Seattle’s leaders quickly showed that they were just as interested in getting the city’s next light rail lines to conform to their policy preferences as they were in touting work to accelerate construction.

“If you’re only approving a one- to three-percent design, and then empowering a bunch of people with no exposure to the cost, no exposure to electoral consequences, you’re really setting up yourself for a lot delay, a lot of bad process,” Trevor Reed, a transportation planner and a member of Sound Transit’s Community Oversight Panel, told The Urbanist.

In guest pieces in The Urbanist, Reed has pushed for agency reform and for following international best practices in station design to save costs, noting Sound Transit’s planned stations tend to be oversized.

The first major debate over Seattle’s ST3 projects was the question of whether West Seattle Link should arrive at Alaska Junction along an elevated track or within a tunnel. The elevated option was clearly cheaper, but would have been a big change for West Seattle residents who are used to the neighborhood looking a certain way. District 1 Councilmember Lisa Herbold, who served on the Elected Leadership Group established to make recommendations on alignments, was a strong supporter of a tunnel concept, and most of Seattle’s transit advocacy groups including Transportation Choices Coalition and the Transit Riders Union supported studying the tunnel concepts.

While a tunnel to Alaska Junction initially came with a $700 million price tag, inflating real estate costs caused the tunnel option to become more comparable with an elevated alignment in 2022, when Sound Transit released West Seattle Link’s draft environmental review. That paved the way for the board to select a tunnel as the project’s preferred alternative — even though those “bottoms-up” cost estimates were still years from being completed. The estimated cost of the West Seattle tunnel has subsequently spiked, suggesting an elevated alignment would have been more economical and prudent.

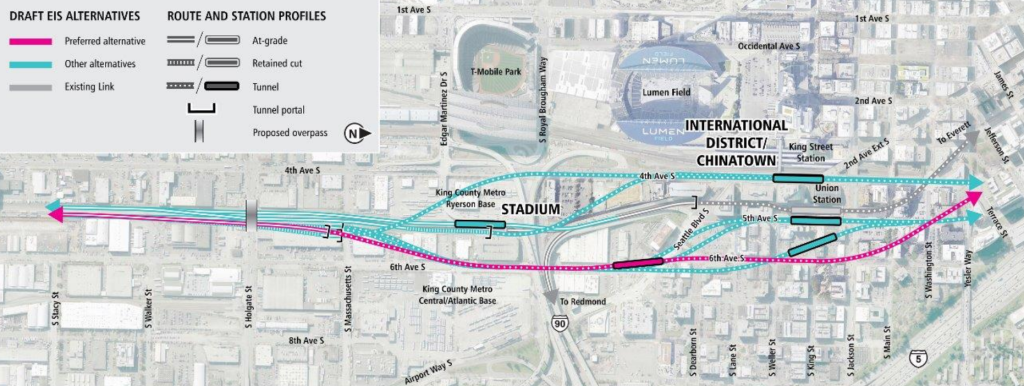

After West Seattle came Chinatown-International District. In 2019, the Durkan Administration asked for “additional study, problem solving, and refinements” for segments of both Ballard and West Seattle Link, with a proposed station location in the CID turning into a major issue.

“Anne Fennessy, the City’s ST3 point person and a close ally of the Mayor, says that Durkan doesn’t want to delay project delivery, despite the request for more options,” the Seattle Transit Blog wrote at the time about a statement that has aged like milk. For a neighborhood that has had transportation decisions foisted upon it for nearly its entire existence, the question of which station location would create the least impacts on the CID continues to be a paramount one, but when it came to the broader conversation, every issue seemed to be prioritized ahead of which location was best for the regional transit system — and what the cost of delay would be.

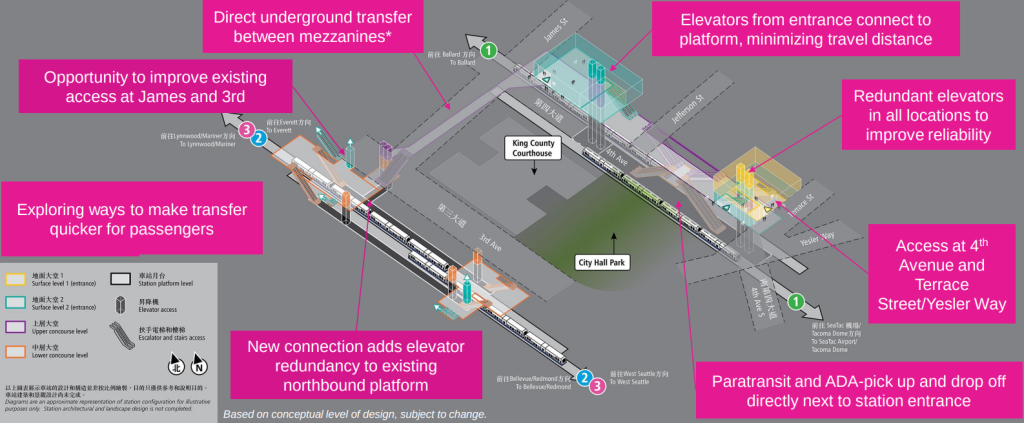

Debate over where to build that CID station simmered until 2023, when Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell and King County Executive Dow Constantine put forward a proposal to move the CID station away from the Jackson Street transit hub and toward I-90. Such a move also came with a shifted station at Midtown, which had been initially envisioned as directly serving First Hill, and would instead be built closer to Pioneer Square station where the County has acres of land available for redevelopment.

Put forward at the last-minute, the switch epitomized the years of process that had led to that point, which had left West Seattle and Ballard Link spinning their wheels. Ultimately, the Harrell-Constantine proposal became Ballard Link’s preferred alternative.

Some delays were avoided. A 2024 vote against studying additional station locations in South Lake Union to limit the impact of construction on traffic disruptions in Seattle’s tech corridor saved the agency an additional 10 months of planning delay, which would have meant a draft environmental review for Ballard Link wouldn’t be ready until late 2026. That vote by the board, framed heavily by the cost of delay, seemed like a watershed moment.

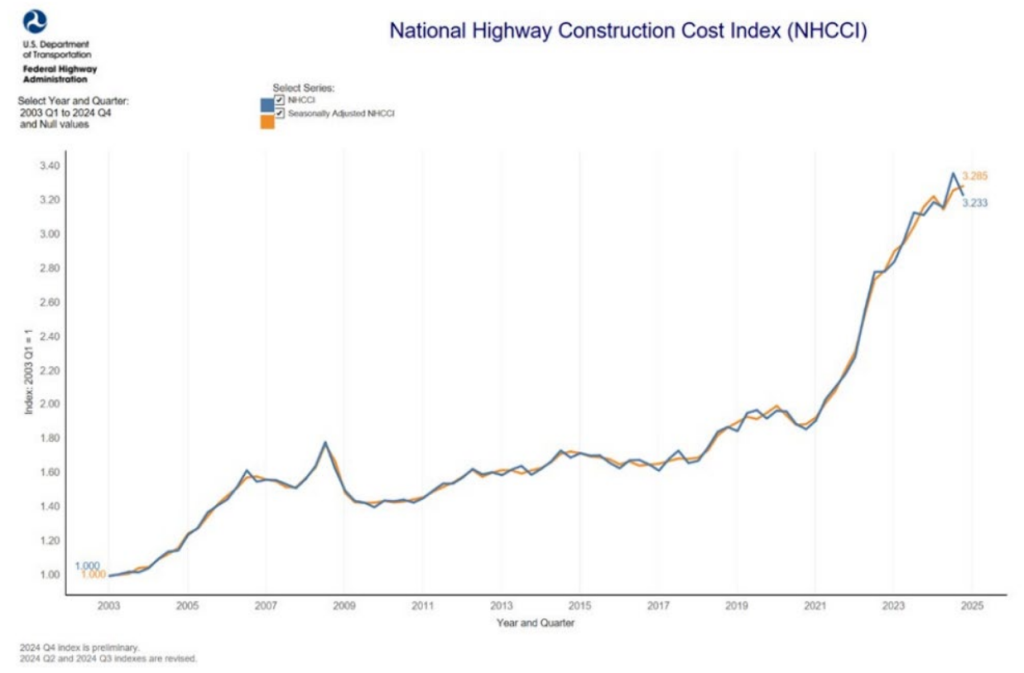

Meanwhile after these years of delays to look at scope changes, Sound Transit went from building projects during a time of very stable inflation on construction projects to a time of record-breaking inflation. Since the end of 2021, highway construction costs have surged 71.5%, a trend that closely mirrors large public transit projects. Those increases are on top of cost increases for right-of-way, since Sound Transit isn’t able to start doing large-scale property acquisition until the end of a project’s environmental review.

“The thing that really hurt ST3 is a lot of the scope creep occurred against a historical anomaly of low cost inflation,” Reed said. “What I think really caught people, and I think caught everyone, off guard, is no one recognized that we are in a historically low inflation environment or low cost environment, and then all of a sudden, all these commitments that were made were completely blown up, because now they can’t get ahead of the cost escalations through delay.”

The question of the second downtown tunnel

Directly on the heels of Sound Transit announcing the latest ST3 cost estimates, Balducci put forward an idea that could help to address those costs: taking a second look at the need to build a second light rail tunnel through Downtown Seattle as part of Ballard Link. The tunnel had been designed as a way to allow trains to both Ballard and Everett to achieve promised headways, but Balducci argued that looking at whether the existing tunnel could be upgraded to meet those frequencies instead could save the agency billions.

Rather than plucking the idea out of thin air, Balducci says that the idea to look at the second tunnel came from years of serving on the board.

“Smart people who care about transit have been asking me this question off and on for a very long time,” Balducci said. “I wasn’t going to bring it forward, probably for many of the reasons that that the transit advocates now are saying — we’d be better off having resilience and redundancy than not, so we should invest in this. But when you’re staring down a $30 billion budget shortfall, then you’ve got to ask questions like, do we deliver minimum operating segments and not go all the way to places we said we were going to go? Do we start cutting back on scope in bigger ways? And if those are questions that we’re having to ask ourselves, then it seemed really important to me to ask the question: do we need the second tunnel?”

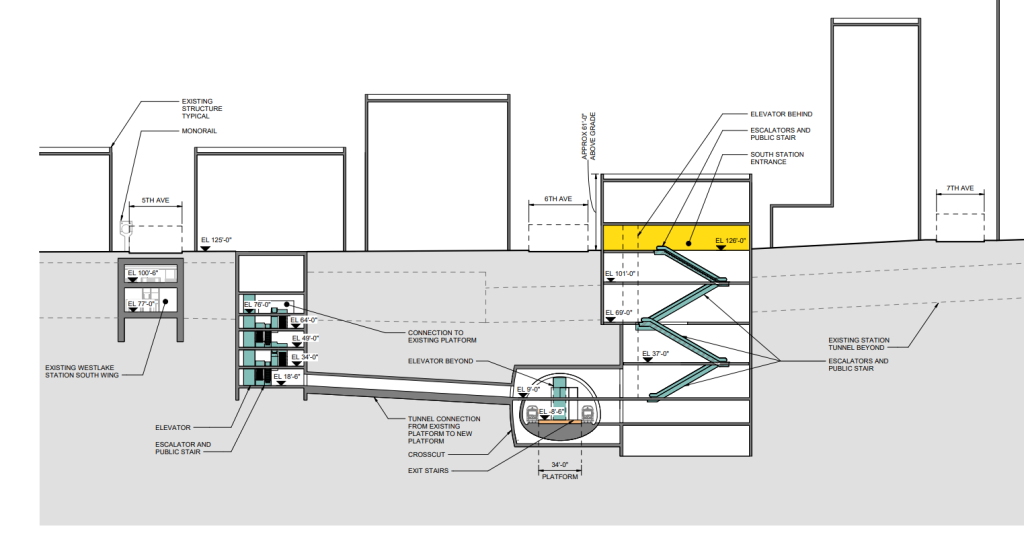

Balducci’s proposal has drawn the ire of some Seattle transit advocates, who worry about tossing a piece of infrastructure overboard that was designed to increase system reliability and resiliency. The existing downtown tunnel remains a big Achilles heel for the entire system. Designed by King County Metro to accommodate buses initially, the tunnel has few crossover tracks, which would allow Sound Transit to respond more nimbly to circumvent breakdowns, and an aging ventilation system.

But some national transit experts think doubling down on the existing tunnel is worthy of study.

“You build a second tunnel when you have maxed out the capacity of your first tunnel,” Goldwyn said. “The first thing you would do, if you’re saying we have more ridership than what our tunnel can currently provide is: can we run more trains per hour? If the answer to that is no, then it’s, can we put in a new signaling system that will allow us to run more trains per hour? If the answer to that is no, then it’s: can you lengthen the trains, can you lengthen the platforms, like all these other things, and then if the answer to all those things is no, you build a second tunnel. I have not ever read anything that suggests that all of those earlier things have been exhausted.”

Beyond not providing relief for Sound Transit’s downtown pinch point, skipping the second tunnel would leave the agency with a conundrum regarding how to connect Ballard Link to the existing light rail tunnel and the system in general. Creating a new rail junction underground would be very challenging, costly, and disruptive undertaking, as explored in depth in a recent Urbanist op-ed. Not building the junction means building a new train base just to serve the new Ballard line — and exacerbating crowding issues at Westlake Station, the likely point where riders of the Ballard line would interchange with the rest of the system.

Reed said spending half of the second tunnel’s high price tag on upgrades to the existing tunnel could leave Sound Transit coming out ahead in the end.

“The tunnels are really high risk, and they’re really hard, and the soil conditions suck. Like, there’s a good chance that we get in and it goes worse than we think it will. What if the $11 billion becomes $14 [billion], what do we do? We end up with just a tunnel,” Reed said. “When you’re talking about numbers this big and a deficit this large, I mean, in an ideal world, yeah, surely, the second tunnel, that’s great and cool. But if the alternative is we’re just gonna have a spur, you know, minimum operable lines to just out of Downtown Seattle to the north, and to Delridge… I’d rather an asset that’s over stressed and heavily used versus an empty one that’s built for a service that is ST4 contingent.”

Mestas said that Sound Transit is already giving the second tunnel an intense look.

“We’re not gonna leave any stone unturned,” Mestas said. “On the second downtown tunnel assessment, we are using a rail simulation model, and that model looks at a whole bunch of things. It looks at reliability and resilience and service and headways, and then we run thousands of scenarios on disruptions of service, degraded service, unusual scenarios, service with and without a tunnel, for example, constructability, cost and schedule, all those things, very much in partnership with our service delivery partners here in the agency and agency oversight so that we can provide the board with well informed information. We’re still very much in the assessment stage.”

Where do we go from here?

Since the latest cost estimates landed with a thud on the desks of Sound Transit board members this summer, staff on the agency’s capital delivery team have been looking high and low for ways to reduce costs within the frameworks already approved by the board, outlining changes to West Seattle Link and to Everett Link last month that would save hundreds of millions of dollars. So far, those tools look to be helping to make projects more affordable for the more straightforward projects like Everett Link and Tacoma Dome Link, where there’s little need for tunneling, major bridge structures, or navigating very dense urban environments — three things that Sound Transit is facing in spades on West Seattle and Ballard.

Board members have already retreated into their corners, with Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell drawing TV cameras to Ballard to make a bold defense of completing Seattle’s projects and Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin directly telling a reporter that she wants to delay them in favor of completing the light rail “spine” north and south.

Mestas is optimistic that the work her team is doing will be able to get the entire ST3 program into a more affordable space — if the board can make a decision and stick with it.

“It’s maybe a challenging inflection point, but I think that a lot of efficiencies and a lot of benefits and the way that we construct is going to be impacted in a really good way, and I think we’re going to see that as we go into construction,” Mestas said. “I think that the most important thing we can do is, as we decide what scope to go forward with and build, and we make these decisions, is we really have to keep these projects going, we need a lot of partnership. We need to make sure that funding is there and consistent, and we have our partners on board. And time is of the essence. Time is one of the biggest factors that will impact your project in so many different ways. So it’s really getting people to hustle around that schedule and move things forward.”

One thing is clear: while West Seattle and Ballard have been stumbling forward in fits and starts since 2016, what happens over the course of the next year is going to be make-or-break for both projects.

“I don’t feel hopeless, but it’s partially because I am engaged in putting one foot in front of the other with the goal of delivering this program no matter what,” Balducci said. “And so if that’s the goal — we’re going to deliver this, we are going to do what we promised the voters — the system will come. The agency has overcome very serious challenges, almost from the very beginning, and overcame them, and has delivered a lot of light rail. And I just think we have to maintain a focus on doing everything we can do to just keep going, and we will find a way.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.