Shared streets have been permitted in the state of Washington for several months but — in Seattle at least — the new street type has been trapped in bureaucratic limbo. That doesn’t mean the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has been spinning its wheels. In fact, a trove of documents and emails obtained from SDOT through public disclosure requests shows work is proceeding inside the department to take advantage of the Shared Streets Law.

The Promise of Shared Streets

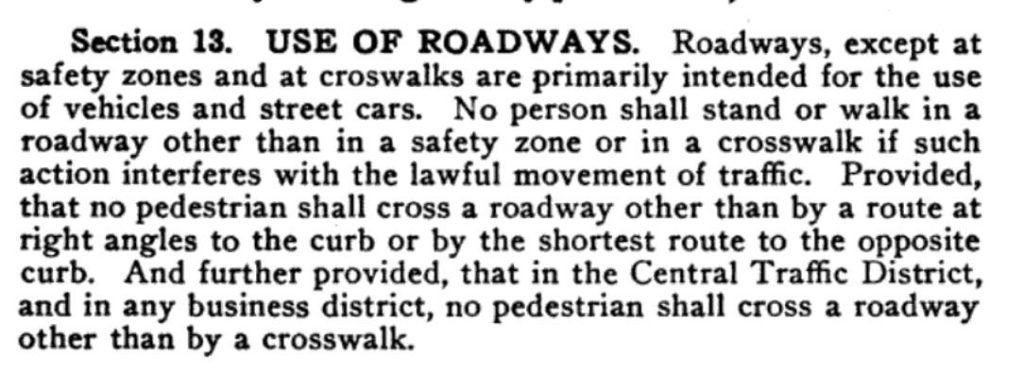

Shared streets flip American traffic laws upside-down. Currently, the portion of the roadway between curbs is the exclusive province of vehicles. You can drive, park, or cycle there — but you are legally prohibited from walking or standing in the roadway, except at designated crosswalks.

Where shared streets are implemented, cars are allowed but pedestrians have priority over other users and are permitted to walk or stand in the roadway. A maximum speed limit of 10 mph governs all users.

According to the text of SB 5595,

(2) Vehicular traffic traveling along a shared street shall yield the right-of-way to any pedestrian, bicyclist, or operator of a micromobility device on the shared street.

(3) A bicyclist or operator of a micromobility device shall yield the right-of-way to any pedestrian on a shared street.

Hold Up. Safer Streets Require Environmental Review?

Governor Ferguson signed the Shared Streets Bill into law on May 17 but implementation has been slow. Clearly, Seattle needs to pass enabling legislation — current city ordinances don’t provide legal support for this new street type — but it is less clear whether the city also needs to complete an environmental review.

Washington's first-in-the-nation shared streets bill, allowing local governments to lower speed limits to 10 mph on specific streets where vehicle traffic must yield to pedestrian, bike, and scooter traffic, is now law. app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?…

— Ryan Packer (@typewriteralley.bsky.social) May 17, 2025 at 11:29 AM

[image or embed]

Attorneys at the City of Seattle have been tied in knots for months over the question of whether an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) is required. SEPA’s stated purpose is to “encourage productive and enjoyable harmony between humankind and the environment” but there are cases where it arguably does the opposite.

Councilmember Dan Strauss, who is leading the charge on shared streets at the City Council level, has said the City could simply draft a Determination of Non-Significance (DNS) and move forward. The city’s legal team is perhaps being more cautious and are keen to inoculate the new street type from legal challenge.

Breaking the Process Logjam

Frustrated with the slow pace of progress, Councilmember Strauss attached a Statement of Legislative Intent (SLI) to Seattle’s 2026 budget, instructing SDOT to provide a legislative proposal for shared streets implementation.

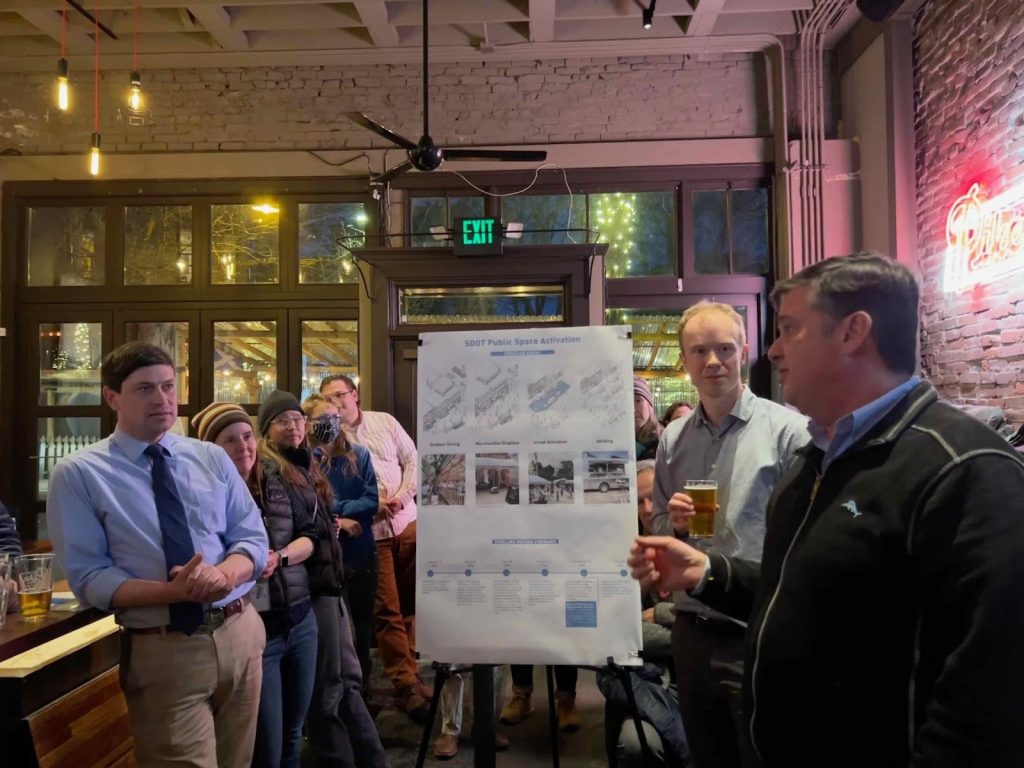

Councilmember Strauss has long sought better tools to improve the streetscape and traffic operation on Ballard Avenue, a popular and historic street in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, which he represents.

Ballard Avenue is lined with shops, restaurants, and bars — many with outdoor dining established during the pandemic — and has interim improvements using paint, posts, and movable barriers. Gaining the legal authority to reduce speed limits to 10 mph and allow pedestrians to circulate in the street can provide better options for permanent improvements to this popular destination.

The Shared Streets SLI passed the Budget Committee on November 14. The response from SDOT is due January 1, 2026, so we will know their plans soon enough, but internal documents obtained from the department reveal their thought process.

The Redmond Way

While Seattle dithers, the City of Redmond has moved to implement the law with less apparent concern for SEPA. Redmond, home to Microsoft, is a suburb of Seattle known for progressive aspirations and policy. According to their draft Street System Plan:

“In Redmond, some local streets will be transitioned to shared streets, which are appropriate on a residential, limited use, or other low-volume street, where the neighborhood desires to create a public space for social activities and play or as an alternative to building conventional sidewalk where there may be environmental or cost constraints. Shared streets are also appropriate on streets with commerce where there is a desire to create an active and attractive people-oriented area.”

Meanwhile, other cities around the state of Washington watch and wait for Seattle to guide the way forward.

What Is Enabling Legislation?

The Shared Streets Law is permissive, not prescriptive, meaning it allows cities to enable shared streets but doesn’t require them. Since most cities have traffic ordinances that mirror state law, when that law changes, city ordinances need to change, as well, and this is accomplished with enabling legislation.

City legislation to enable shared streets can consist of five elements:

- Definition

- Enabling Language

- Signage

- Speed Limit

- Driving Regulations

1. Definition. Since this is a new street type, it needs a name and definition, which can mirror state law: “Shared Street means a city street designated by placement of official traffic control devices where pedestrians, bicyclists, and vehicular traffic share a portion or all of the same street.”

2. Enabling Language. This delegates authority to the relevant body or individual: “The City Traffic Engineer is authorized to designate any non-arterial street or alley, or any part of a non-arterial street or alley as a Shared Street in accordance with Senate Bill 5595.”

3. Signage: “Upon approval, the City Traffic Engineer will install and maintain appropriate markings, signage, barriers or other devices to clearly indicate the speed limit and shared street designation.” Since true shared streets are new in the United States, local authorities will need to glean guidance from existing authorities like Federal Highway Association and the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), and perhaps exercise engineering judgment to ensure clarity until nationwide standards are developed.

4. Speed Limit: “A Shared Street has a maximum speed limit of 10 miles per hour.”

5. Driving Regulations: Lastly, the key clause that redefines rights and responsibilities on shared streets, again mirroring state law: “Vehicular traffic traveling along a shared street shall yield the right-of-way to any pedestrian, bicyclist, or operator of a micromobility device on the shared street. A bicyclist or operator of a micromobility device shall yield the right-of-way to any pedestrian on a shared street.”

Once All Streets Were Shared Streets. What Happened?

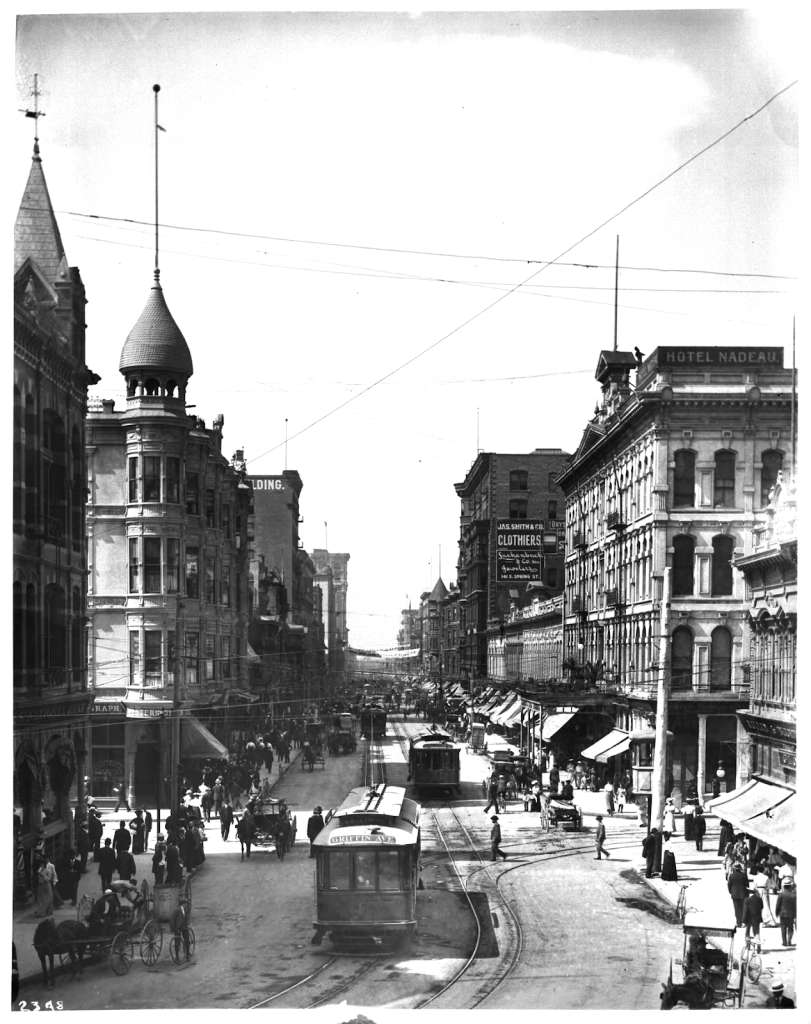

A century ago, American streets were shared public spaces. People walked freely in the roadway, children played in them, vendors sold from carts, and perhaps a streetcar threaded a slow-moving mix of pedestrians, carriages, and early automobiles. Horses did their business in the street, as well, so it wasn’t all roses but American streets functioned more or less the same as they had around the world since the invention of cities.

That changed starting in January 1925 when Los Angeles passed its traffic ordinance. Cars were proliferating — and killing pedestrians at an alarming rate. The solution was to relegate people to the edges, require them to cross at crosswalks, ticket them for jaywalking, and then to launch a propaganda campaign funded by the motor industry.

LA’s new law propagated quickly across the country and that spread accelerated when it was adopted by the National Conference on Street and Highway Safety as the blueprint for the 1928 Model Municipal Traffic Ordinance. Soon, every state in the Union would ban shared streets and effectively prohibit speed limits lower than 20 mph.

Only now, 100 years later, has Washington State lifted the ban on shared streets — the first in the nation. So the race is on to build the first fully legal shared street in America in a century.

The SDOT Team Set to Bring Shared Streets (Back) to Seattle

Interviews and public disclosure requests reveal that SDOT staff members are enthusiastic about the new powers the Shared Streets Law will grant them, once enabled. Responsibility for shared streets will fall to Ashley Rhead, SDOT’s Pedestrian and Neighborhood Projects Manager, working under Director of Project Development Jim Curtin and Deputy Director Brian Dougherty. Rhead’s group deals with neighborhood greenways, home zones, safe routes to school, school streets, and sidewalks.

City Traffic Engineer Venu Nemani has been deeply involved in developing a strategy for implementing shared streets, while longtime neighborhood greenway champion and Neighborhood Projects Manager, Summer Jawson, tracked the bill and reported progress to SDOT Director Greg Spotts, and later Interim Director Adiam Emery.

It is important to note that the shared streets law is a tool that cities can use to improve all kinds of streets. It is a legal designation that changes the rights and responsibilities of users and opens new design possibilities. A neighborhood greenway, for example, can be a shared street and allow pedestrians into the roadway, or it can remain a typical neighborhood street where pedestrians are expected to use sidewalks. Transportation departments implementing SB 5595 will have a choice.

Let’s take a look at the ideas brewing at SDOT.

Home Zones and Other Circulation Plans

Documents obtained via public disclosure request reveal robust internal discussion at SDOT around shared streets. One of the more intriguing examples is the opportunity to create better home zones.

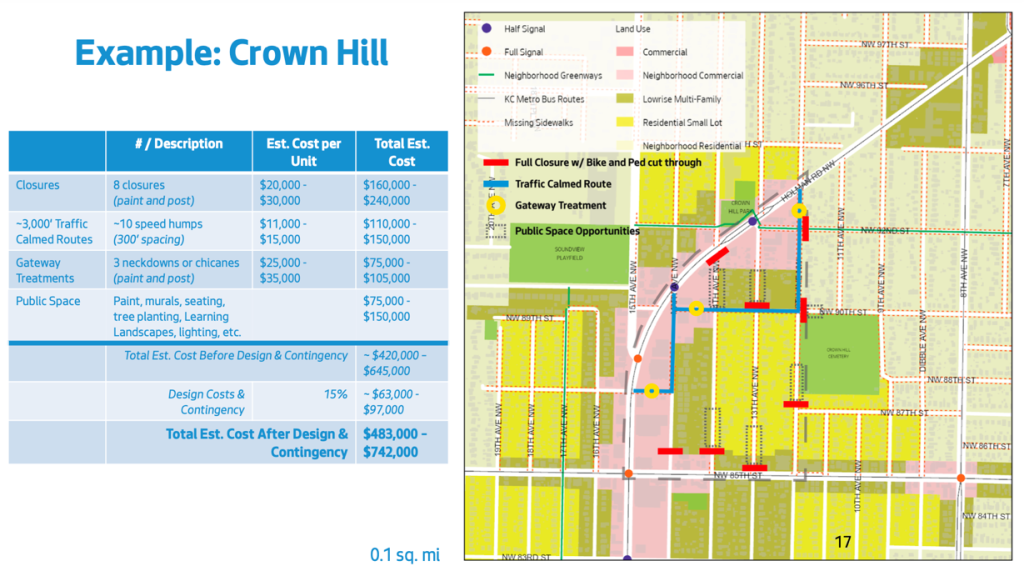

A home zone is an area of neighborhood streets bounded by arterials where diverters are used to make the zone less attractive for cut-through traffic. The result is a reduction in traffic volumes in the interior while maintaining full vehicular access. Once traffic volumes are reduced, there are opportunities for traffic-calming and the provision of additional public space—ideal places to flip the modal hierarchy to favor pedestrians, consistent with SB 5595.

This approach is most similar to London’s Low-Traffic Neighborhoods (LTNs) but uses techniques similar to Barcelona Superblocks, as well as larger city center traffic circulation plans like those found in Ghent, Brussels, Paris, and Groningen.

SDOT staff are internally proposing what they call “Home Zones 2.0.” Currently, Seattle’s Home Zone program provides spot improvements to reduce speeds, typically requested by residents, but generally doesn’t decrease volumes.

Home Zones 2.0 would take a more comprehensive approach, to measurably decrease vehicle volumes and speeds and increase walking, biking, and playing. Home zones would be “physically identifiable by drivers, walkers, bikers” when they enter the zone.

SDOT staff illustrated how a new and improved home zone might work on Seattle’s Crown Hill, a mixed commercial and residential neighborhood that generally lacks sidewalks. Diverters, shown in red, prevent cut-through car traffic while allowing people walking and rolling to pass. Gateway treatments, shown as yellow circles, let you know you’re in a traffic-calmed area.

The chronic lack of sidewalks in much of South Seattle, as well as vast areas north of N 85th Street, make this kind of traffic-calming imperative. At the current pace, it will be as many as 1,800 years before the city finishes building sidewalks in Seattle. In the meantime, these are de facto shared streets. Children walk to school on them, mixing with vehicular traffic in a shared space, but lacking the rights and pedestrian-compatible speed limits they need and deserve to travel safely.

Where Are Shared Streets Going First?

Neighborhood Greenways present the prime case for shared streets treatment in Seattle, which has a loose network of these streets across the city. Neighborhood greenways are non-arterial streets with lower traffic volumes that have been enhanced with traffic-calming, wayfinding, and improved arterial crossings. During the pandemic, to provide space for people to gather outdoors, Seattle converted several of these to “Healthy Streets,” with the addition of “Street Closed” signs, which was, as the time, the only tool available under state law to permit pedestrians to walk in the roadway.

According to internal documents, Healthy Streets are likely to be the first to receive shared streets designation, along with festival streets and school streets. Neighborhood greenways could follow. The changes are likely to be modest at first — with the addition of signage — paving the way to more robust treatments in the future as budget allows and SDOT standards develop.

SDOT also hopes to roll out what they are calling the Neighborhood-Initiated Safety Program (NISP, sometimes playfully called “nispy”) in 2026 that lets residents nominate areas for traffic-calming, possibly merged with the Home Zones program. That would be a welcome development. Since the Your Voice, Your Choice (YVYC) and Neighborhood Street Fund (NSF) grant programs were discontinued, there has not been an accessible outlet for neighborhood organizing around safer streets.

SB 5595 will not transform Seattle overnight — that much is clear — but shared streets represent a generational opportunity to reclaim safe space for walking, rolling, and community life. Cities around the world already treat low-speed, pedestrian-first streets as routine public infrastructure. With enabling legislation on the horizon and SDOT laying the groundwork, Seattle has a chance to join them. The question now is whether the city can cut through its own red tape and deliver the kind of streets residents have long said they want.

Mark Ostrow serves on the board of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways and is a core leader of Queen Anne Greenways. Follow him on Bluesky at @qagggy.