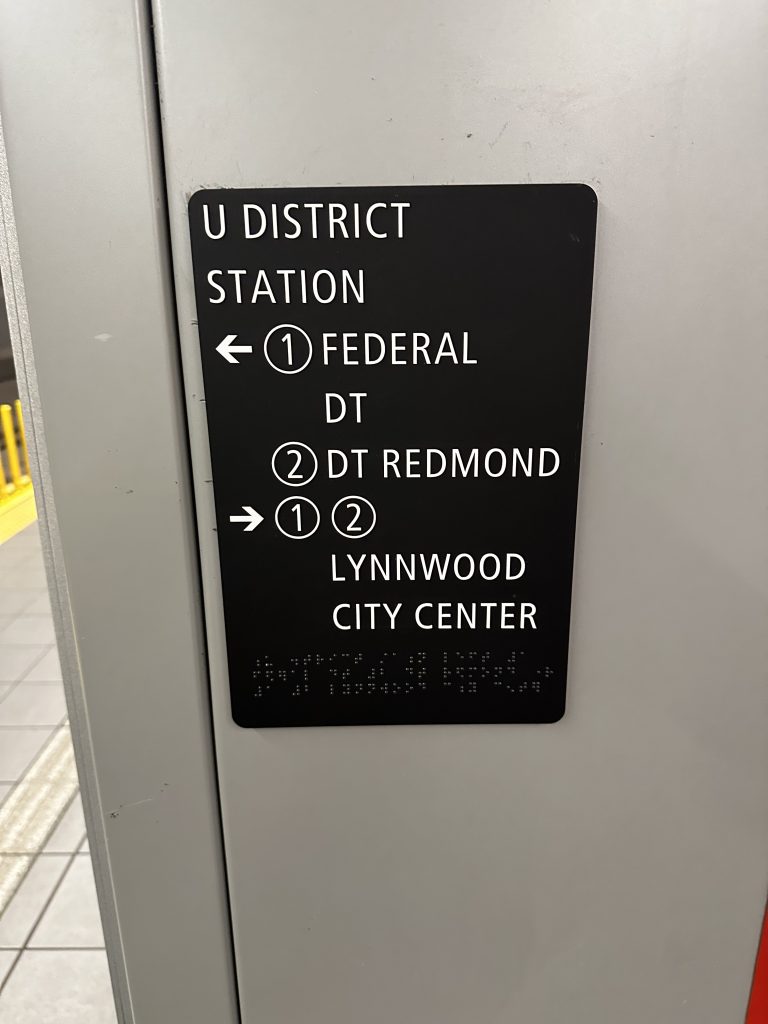

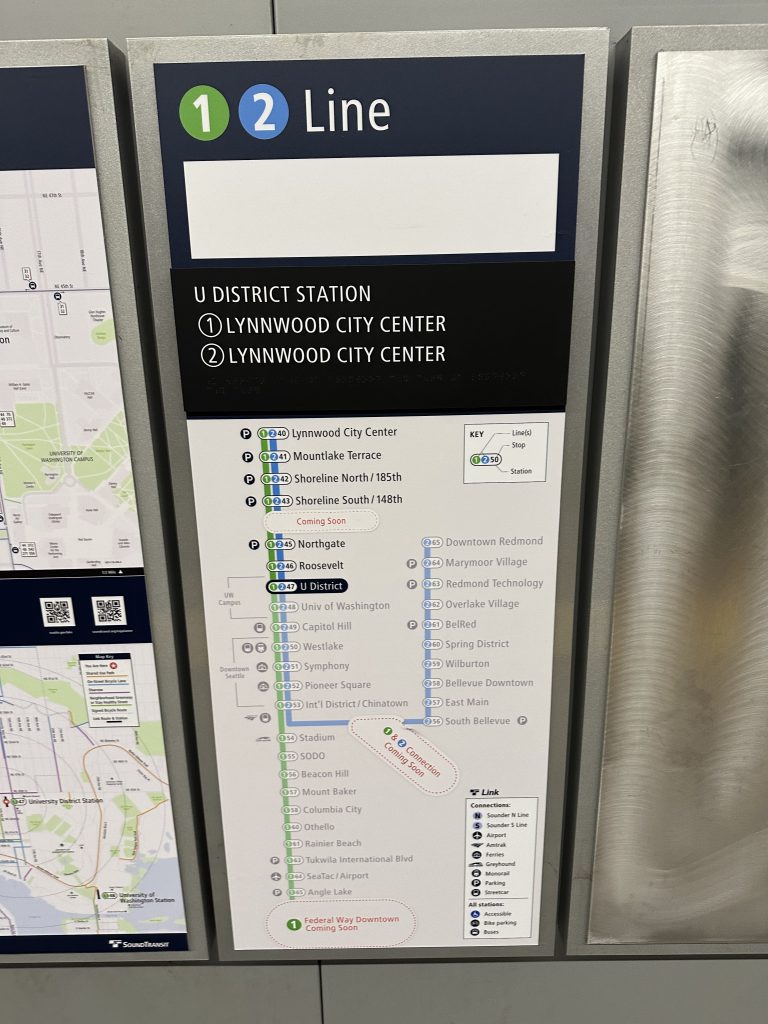

Sound Transit light rail riders must contend with a bevy of befuddling station names: Federal Way Downtown, Downtown Redmond, Lynnwood City Center. It’s a recipe for confusion and wayfinding blunders.

While Sound Transit has sought to reform its station naming policy, names remain an embarrassing mess that makes navigating the system challenging, especially for visitors and new users on the system.

In the wake of the University Street Station renaming debacle in 2020, Sound Transit revised its station naming policy in the hopes that it would deliver better results. The policy on paper was somewhat promising. However, as it has been translated into physical use throughout a quickly growing system, it is already showing that reforms didn’t go far enough.

Urbanist contributing reporter Ryan Packer dropped a post on Bluesky the other week pointing out that new signage at a Rainier Valley station showcased ambiguous wayfinding for a variety of key stations, but also neglected to highlight the direction for Downtown Seattle. It set off a firestorm of discussion on the social media platform.

Transit riders broadly panned the signage and station names on social media:

- “Now you might think the ‘Downtown’ on this sign was for Downtown. But no! It’s for the ‘downtown’ of a city called Federal Way, which is the opposite direction of downtown Seattle.”

- “PNW so passive aggressive, even the transportation signage refuses to be direct, clear, and helpful.”

- “Absolutely no way that someone gets confused and reads this as ‘Federal Way, Downtown, and Airport’, right?”

When people think of “Downtown” in this region, they almost exclusively think of Downtown Seattle, and perhaps secondarily Downtown Bellevue or Downtown Tacoma. But Seattle has no station with a “Downtown” moniker attached to it because there are multiple stations serving the city center and riders are better served by identifiable station names representing specific parts of the city center anyway.

To its credit, Tacoma is not arrogant enough to have a Link station emblazoned with “Downtown,” and yet it has far more bragging rights to a downtown than any suburban city to seize the mantle.

The bedroom communities of Federal Way and Lynnwood appear to be engaging in “field of dreams” wishcasting hoping ‘if you name it, they will come.’ Back in reality, giving a freeway-adjacent patch of strip malls the name “downtown” or “city center” has yet to summon a downtown in these cities. Though the lofty aspirations may one day bear fruit, delivering major urban redevelopment projects, that day could be decades away. Regardless, wishcasting doesn’t make for good station names and wayfinding.

In isolation, it may be rational for Federal Way to refer to its core district as Downtown Federal Way in local mediums for branding just as it may be rational for Lynnwood to market its core urban area to its local residents as Lynnwood City Center. But Link operates as a regional system, passing through many small urban districts and a few larger ones. Given that reality, it is more useful to riders that station names are succinct and offer unique placemaking and geographic information rather than regurgitated branding and marketing terminology over and over again.

Sound Transit should ban the use of “Downtown” and “City Center” in any official station names, regardless of how significant a place is. The use of “Downtown” and “City Center” should be limited to aiding riders in specific contexts in system wayfinding materials, such as understanding the direction of a train or a grouping of stations.

For instance, in New York City, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority provides station wayfinding signs that indicate platforms and train services that are headed in the direction of Downtown or Uptown when in Manhattan or particular city boroughs (i.e., Manhattan, Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn). Sound Transit also has special wayfinding diagrams that group stations by geographic areas in some cases, such as Downtown Seattle and the University of Washington campus.

Those are appropriate cases for using “Downtown” and “City Center” within the system.

In cases where cities want to highlight the primacy of a principal station, Sound Transit should look to the British for a simple solution: tacking on “Central” to the end of a station name.

In London, the Underground has plenty of station names containing the moniker like Hounslow Central, Acton Central, Wembley Central, and Hendon Central. All of the stations have alternative community stations of the same placename, so the “Central” helps riders know that the station is likely the more prominent station for the community. What one doesn’t find anywhere on the Underground is a station name with “City Center” or “Downtown” in it.

But there’s also nothing wrong with giving the centralmost station of a community just the name of the city. Bellevue Downtown, Federal Way Downtown, Downtown Redmond, and Lynnwood City Center could just as well be Bellevue, Federal Way, Redmond, and Lynnwood. Dispensing with qualifiers is to the point. People understand it. And we know that because the Sounder commuter rail stations use this straightforward format for each city served by a station. People intuit that Kent Station is in the city center.

Part of the problem with Sound Transit’s station naming policy is that it’s a classic design-by-committee misadventure. There’s a behind-the-scenes staff process, there’s a public survey process, there’s a city influence process, and then there’s a process for busybody board members. Over the years, it’s usually been the latter two that have been most influential on what ultimately turns up on signs and materials, even upending commonsense public feedback.

And, in a way, that makes sense: every city wants to believe that it is unique and prominent, so many smaller cities seek to evoke that in their station names with honorific qualifiers at the cost of a cohesive strategy to support easy system navigation.

But it’s not just the use of “Downtown” and “City Center” in station names that are problematic. For instance, the station naming policy doesn’t explicitly resolve how to deal with relational station naming practices, which can result in oddities and even misnomers.

To be sure, Sound Transit has it right with Shoreline North/185th and Shoreline South/148th by placing the relational geographic qualifier after the placename. But that’s in part what’s off with South Bellevue, which reverses its qualifier. “Bellevue” should at least be the leader in the station name to clearly drive attention to a principal place.

But the station name also breaks the agency’s basic principles in regards to using geography: the station is actually located in the west-central part of the city, commonly referred to as “Enatai” or “West Bellevue,” not South Bellevue, which isn’t a neighborhood anywhere in the city. The station name naturally can mislead people into thinking South Bellevue is a neighborhood.

As a best practice, Sound Transit shouldn’t permit a situation like South Bellevue and instead should push for an actual placemaking name approach in similar station contexts. Seattle’s infill station at NE 130th Street, now known as “Pinehurst,” is a good example of using a real neighborhood name for placemaking. Thus, “Enatai” could be a natural choice for Bellevue’s southernmost station.

Then there’s International District/Chinatown Station in Seattle. It may be a small thing to some, but it’s a real disrespect to the Chinatown-International District (CID) neighborhood — the neighborhood in which Sound Transit’s headquarters are located — that the station name is malformed. CID leaders have urged the agency to use the neighborhood’s actual name rather than the inverted version. It’s long past time that the agency corrected the name.

Sound Transit needs to get its station naming policy right and propose new names for offending stations. The problem gets harder to solve the longer that Sound Transit waits and installs more and more signage for poorly named stations. One idea to streamline the process: the revised policy should explicitly delegate naming decisions to agency line staff to keep boardmembers focused on upstream decision-making rather than getting bogged down in the weeds of political naming fights.

With the Federal Way Link Extension opening this weekend and Link 2 Line service finally crossing Lake Washington sometime in 2026, there isn’t sufficient time to adjust the station naming policy, propose new names, approve new names, and then replace all system wayfinding materials. It’s a longer-term project than that, but it should be a priority to accomplish as soon as possible, hopefully before the next set of expansions.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.