This week Sound Transit board members got a deep dive on what it would take to extend light rail to Ballard without building a second rail tunnel under Downtown Seattle at the same time, a big deviation from the current plan. While initial analysis did confirm the potential to save up to $4.5 billion, those gains would come at the cost of further delays to the overall Ballard Link project, impacts on transit riders that could be yearslong, all on top of significant risks that could eat away some of those savings.

King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci put forward the idea this summer in response to significant cost overruns that threaten light rail projects across the region, framing it as an out-of-the-box idea with the potential to save Sound Transit billions. Balducci chairs the Sound Transit board’s Systems Expansion Committee.

Next week, the full board will be tasked with deciding whether the issue is worthy of additional study, as board members start to consider scenarios that will bring Sound Transit’s long-term financial plan back into alignment. All signs so far point to that determination as being a clear no, with numerous board members Thursday expressing major concerns about the impact of phasing in a second tunnel later and uncertainty around actually realizing those significant cost savings.

Saving $4.5 billion could mean reducing Sound Transit’s expected deficit by more than 13%, and bring down the cost of the $22.6 billion Ballard Link project by nearly 20%.

If creative options like phasing in the second downtown tunnel are indeed off the table, that will likely leave more straightforward decisions for board members in 2026, like deferring entire lines or phasing them in sections that fall short of what was promised voters. While Sound Transit’s capital delivery team, led by Deputy CEO Terri Mestas, have been uncovering significant cost savings by redesigning stations and considering new options for guideway construction, those moves alone are unlikely to close the entire affordability gap.

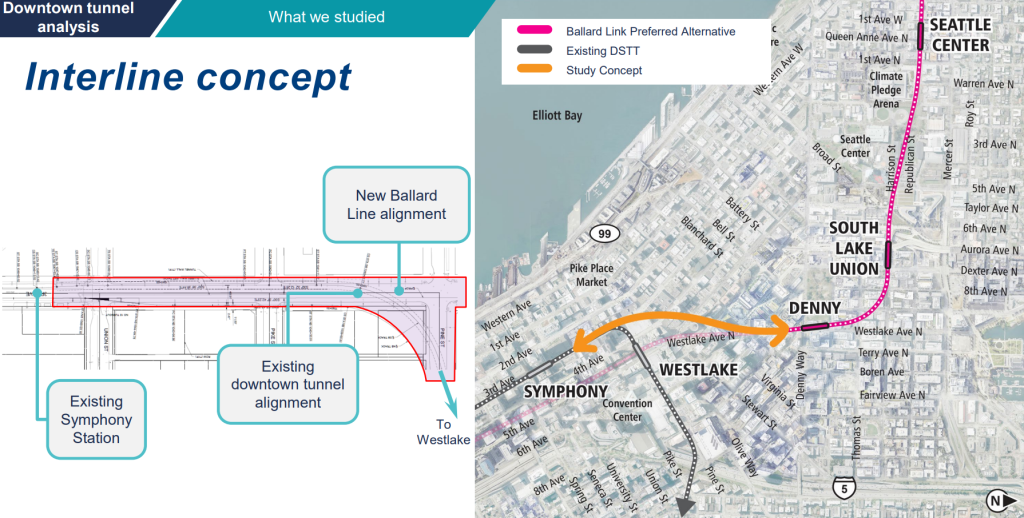

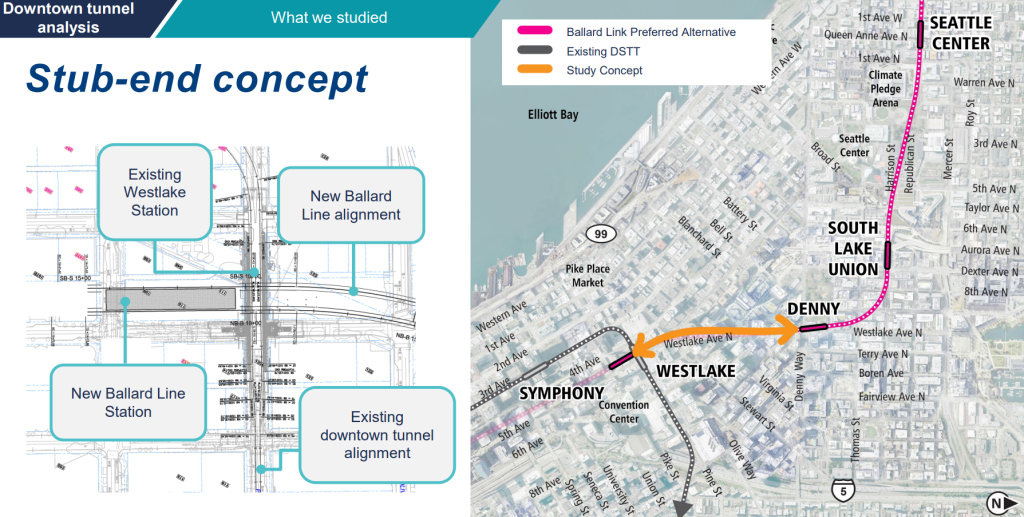

Members of the board’s Executive Committee were shown two different options for a truncated Ballard line: an “interlining” alternative that would utilize the existing Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel (DSTT) to carry trains from Ballard, and a “stub-end” alternative that would require Ballard riders to transfer to access the rest of the system. Of those options, interlining could save the most money (up to $4.5 billion, compared to $4 billion) but they both come with significant risks and uncertainty.

Common to both options would be another two-year delay — or “likely longer” — to the environmental review process for Ballard Link. That alone could be enough to put the issue to bed, with those delays adding costs all on their own as inflation takes its toll on Sound Transit’s buying power.

Construction hurdles also come into play. While there would be fewer overall stations to build, construction would become more complex in some ways due to the need to start tunneling from Queen Anne, meaning the overall timeframe for construction wouldn’t be reduced much. Those delays could all push Ballard Link’s grand opening until at least 2041, compared to an initial opening date of 2035 presented to voters nearly a decade ago.

Making this decision in December does mean leaving out the voice of Seattle Mayor-Elect Katie Wilson, who is set to join the board next month. King County Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda, who has signaled a desire to be a strong advocate for Seattle’s light rail projects, won’t have much time to get up to speed ahead of her first board meeting next week either.

The interline concept

Under the interline concept, Ballard Link would no longer include a station at Westlake, instead tying into the existing 1 Line between Westlake and Symphony Stations. A separate alternative was considered that connected east of Westlake Station instead, allowing Westlake to remain a central transfer location, but that would require tunneling work that Sound Transit’s analysis determined is “near fatally flawed.”

The interlining option would provide riders with the biggest benefits, namely allowing them to transfer between all lines without having to change stations at all. But it comes with big impacts to the existing system as well, including an estimated three-year closure of the existing 1 Line to shore up the existing tunnels, excavate the new one, and install and test the new systems. The Third Avenue transit mall on ground level would also have to close for nearly a year to install the cut-and-cover box required to retrieve the tunnel boring machine.

On top of that, building a new tunnel underneath Third Avenue and connecting to the existing one would be “challenging and risky” — with a “very high risk” of damage to the existing tunnel even with proactive protections installed, Sound Transit staff said. Work would occur in close proximity to nearby structures, even with significant property acquisition needed in the area. A separate cut-and-cover tunnel would need to be built to retrieve the tunnel boring machine after it completes the planned connection, which would add months of time.

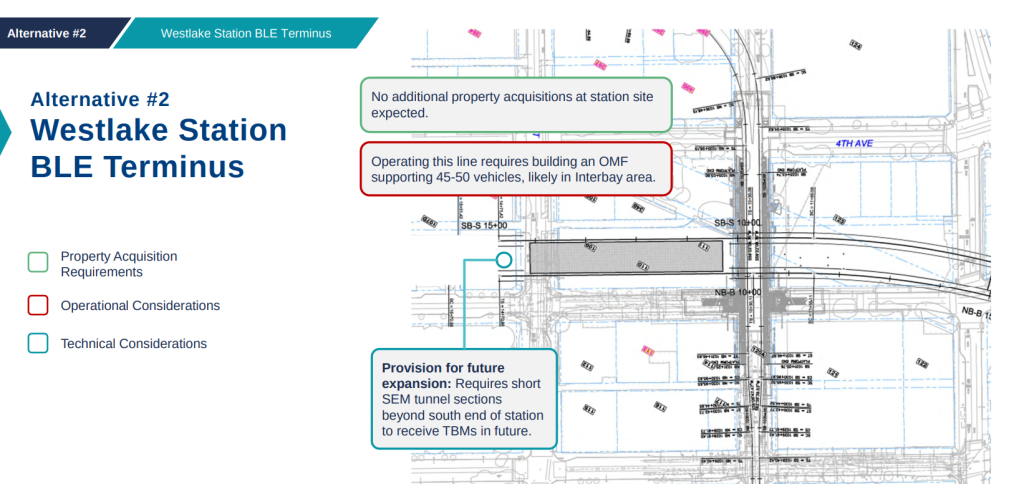

Stub-end concept

Compared to the interlining option, the stub-end concept would come with much fewer construction impacts. It would essentially build a fully independent rail line between Ballard and Westlake, including a fully independent station at Westlake. Riders heading elsewhere would need to connect to other trains, adding transfer time to all trips.

While the line could eventually connect to the rest of the system via a future phase, it would need its own operations and maintenance facility, likely sited somewhere in the Interbay area. Even with that expense, it would still be expected to save $4 billion, though adding on a full operations and maintenance facility (OMF) into the project adds much more risk, especially considering urban land prices in Seattle.

No additional property acquisition would be required with this alternative outside that OMF, as it would be built within the same right of way as the current planned project. All of these design elements add up to much less risk than the interlining option.

Creating a stub line independent of the existing system could potentially allow Sound Transit to build Ballard Link as an automated line, which has been discussed as a potential feature of future lines.

Thursday’s presentation didn’t spend much time on a central question Balducci’s request sought to answer: would the existing Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel be able to handle the number of trains expected by the time ST3 is fully built-out? Ultimately, the information produced to date by Sound Transit only goes so far as to say it “could” be modified to handle those train frequencies, but that additional study would be required.

“The current system has a number of constraints that limit the ability of Sound Transit to achieve a two-minute combined headway. If upgrades are not implemented (ventilation, traction power, platform capacity, special trackwork, communications, train control/signaling system) the system would not be able to accommodate a headway less than nine minutes on each of the three lines,” a Sound Transit report dated this month noted.

Sound Transit is already operating at 8-minute peak frequencies on the 1 Line and plans to do the same on the extended 2 Line next year, even before accounting for the potential for ridership growth that could push the agency to increase frequencies to handle the passenger load.

Board members skeptical of further study

Sound Transit board members, especially Snohomish County Executive and current Chair Dave Somers, were quick to conclude that the analysis shown Thursday proves studying these options any further would be a dead-end. It was Somers who chose to have the discussion this month in his committee instead of in the usual Systems Expansion committee, which Balducci chairs.

“I am quite convinced that continuing to pursue this would be a very bad idea,” Somers said. “The reason we headed down this path in the first place was the thought that we could save really significant dollars. And $4 billion is a lot, but that’s an estimate.”

Somers noted that the second downtown tunnel, in contrast with other projects like West Seattle or Everett Link, is a cost currently set to be shared across the entire Sound Transit taxing district, meaning that cost savings from eliminating it wouldn’t necessarily free up funding for Seattle-specific light rail projects like the rest of Ballard Link.

“I think this was really valuable time spent. I am sort of absorbing information, but tend to agree with you Chair [Somers],” Tacoma Councilmember Kristina Walker said, raising concerns that Sound Transit staff’s estimation of the potential cost savings start at $0, given the number of risks involved. “If we could fully realize the $4 billion or the low end was half that or something, it feels like that would be a different conversation. We do need to find savings where we can, but it does seem that the negatives on this outweigh the positives, because we want a system that works not just to save those dollars.”

Pierce County Executive Ryan Mello, who is likely to be the board’s next chair, cited the cost of delay as the main reason to stop pursuing this avenue of study. The board has become much more sensitive to the cost of delay in recent years, deciding against studying additional options for Ballard Link in South Lake Union last year for the exact same reason.

“This is one of those really big, bold ideas that we have to ask ourselves about. So I’m really grateful that we did for so many reasons,” Mello said. “My major concern is more delay. We know one of the biggest drivers we have for cost is time. And so not only am I really, really concerned about spending a year or more diving [in] even more here on this question. I think that uncertainty is really concerning for me. That uncertainty is not good for Sound Transit, the uncertainty is not good for one of our major partners we rely upon to help fund our system, the Federal Transit Administration.”

But Balducci pressed her fellow board members to continue probing into this issue, noting the significant amount of dollars that it could unlock in the context of a $34 billion shortfall through 2046.

“I understand what a range is, and the range starts zero, it goes to $4 billion, but it goes to $4 billion. There’s not a single other thing we’re considering that is going to potentially come with that range and possibility of cost savings, and therefore we have got to take this seriously,” Balducci said, suggesting that the board could go to an outside group for additional analysis, like the agency’s Technical Advisory Group (TAG). “I just want to state really clearly the potential benefits of operating with a single tunnel. The potential benefits are cost savings and a much better integrated system.”

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell was in attendance at Thursday’s committee meeting, but kept his camera off during the entirety of the discussion on the second tunnel. During campaign season earlier this year, Harrell had ramped up his outspokenness, urging his Sound Transit colleagues not to cut Seattle stations, but ultimately he lost a close election to Wilson, a long-time transit advocate.

While it doesn’t look likely that the board will continue to pursue this idea into 2026, an actual decision will come at next Thursday’s board meeting.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.