Preventing the worst impacts of climate change demands systemic changes across many sectors of society, and housing is key among them. As a climate scientist and past lead author of four Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, I’ve spent my career examining how best to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. One solution always stands out as a double win for both mitigation and adaptation: building more dense housing within vibrant walkable neighborhoods.

Urban density is often misunderstood. To some, it conjures images of overcrowded cities with nothing but concrete and asphalt. But it can and has been done well with massive environmental and social benefits. It allows people to live closer to friends and family, as well as to where they work, shop, and play. And with these benefits, we all significantly reduce climate pollution and other pollutants that damage human health.

As Seattle grows and corrects its deeply flawed urban planning policies and decisions of the past, we have the opportunity to choose our future: to be a vibrant, efficient, and sustainable community, or a place that is simultaneously dying socially and economically unaffordable.

Housing as a climate solution

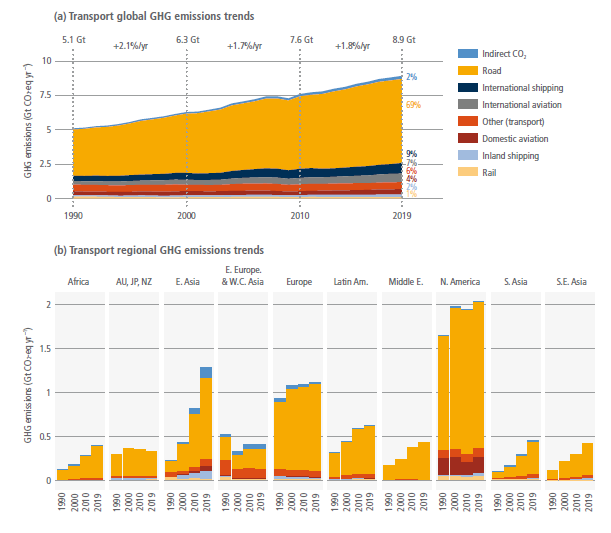

Just road transport — largely driven by our car-dependent urban form — accounts for 58% of Seattle’s core GHG emissions from the sources that improved city policies can meaningfully affect. But even this large faction obscures the huge magnitude of emissions that have been induced by Seattle’s historical choice that made it illegal to construct more housing across most of the city. This choice has led to a Seattle that is now suffering from a significant housing shortage. Specifically, decades of restrictive zoning policies have limited people’s housing and neighborhood choices while driving up the cost of the existing housing stock and forcing lower-income workers to commute from increasingly distant suburbs.

Close-in and connected city neighborhoods with more housing flips this equation on its head. By permitting the development of affordable and vibrant mixed residential and commercial neighborhoods, we reduce the distances people need to travel and make low-carbon transportation options like walking, biking, and public transit the desired option. Research and the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (Chapter 8) find that transitioning to more walkable, transit-oriented neighborhoods is one of the most effective ways to cut energy use and emissions, while at the same time improving both our quality of life and addressing inequality.

Enabling Low-Carbon Transportation

Building transit, such as the Seattle region’s growing Link light-rail system, is not enough. To be effective at addressing problems, it must be paired with a sufficiently dense and varied supply of housing near transit hubs that gives more people an affordable choice to use it. This obvious approach is already in Seattle’s Climate Action Plan. We just have to make Seattle’s policies match our plans and emissions reduction targets.

Further, by reducing the necessity for all trips to be by car, more walkable neighborhoods also free up valuable space currently consumed by parking lots and wide roads, which can instead be repurposed for green space and green infrastructure to capture stormwater runoff. The IPCC confirms that creating more space for small urban wetlands and forests is also a climate adaptation solution, as they are buffers against heat. During climate emergencies — like heatwaves or storms — compact communities with walkable access to resources and services are inherently more resilient.

Buildings are also a major source of emissions for Seattle, and the concentration of buildings enables the future deployment of more energy-efficient infrastructure, such as district heating and cooling systems, which are not viable in sprawling neighborhoods.

Debunking NIMBY Myths

Opponents of more infill housing development, often referred to as “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY) advocates, frequently argue that new housing harms the climate and environment. However, these claims are not only misleading but are simply contrary to all of the best climate science available.

Claim #1: New housing development increases emissions. Critics often claim that building new housing generates significant emissions, from construction materials to energy use. While it’s true that construction has an initial carbon footprint, the long-term emissions savings from dense, energy-efficient housing vastly outweigh these upfront emissions.

In Seattle, where car dependency is a major driver of emissions, preventing housing development within the city has forced growth outward. This has led to more suburban sprawl, longer commutes, and higher emissions relative to an alternative if Seattle had just allowed more housing to be built. This destructive dynamic continues today.

Claim #2: Housing development destroys trees and green spaces. Another common argument is that new housing destroys green spaces. However, concentrating housing in dense urban areas actually preserves more open land. Compact development uses land more efficiently, leaving more room for forests and wetlands, which also sequesters carbon. By contrast, sprawling development fragments ecosystems and consumes vastly more land per capita.

Claim #3: High-density living reduces quality of life. Some argue that dense housing leads to overcrowding, congestion, and reduced quality of life. Yet, when done thoughtfully, dense development creates vibrant, livable communities with easy access to amenities, public transit, and green spaces. Compact, walkable neighborhoods foster social connections and reduce time spent in traffic — improving mental health and well-being. NIMBY arguments often ignore these broader benefits, focusing instead on preserving the status quo. But the status quo is unsustainable—both for the climate and for future generations.

Claim #4: Housing growth comes at the expense of social cohesion and racial equity. Of course, building more dense housing is not without challenges. To succeed, we must pair it with policies that ensure affordability, equity, and inclusivity. High-density housing should not lead to gentrification or displacement but should instead provide opportunities for all.

Seattle’s history of exclusionary zoning has contributed to both its housing crisis and its climate challenges. Reversing this legacy has begun through the newly passed State laws on transit-oriented development and zoning as well as some elements of the Seattle comprehensive plan, but further bold action to foster new housing construction, small shops in our neighborhoods, and walkable/bikeable neighborhoods is needed. To fully address the hole that we are in, we will also need to pair it with investments in affordable housing while continuing to invest in public transit.

Seattle, with its new leadership that deeply understands these issues, robust climate goals, and progressive spirit, is well-positioned to lead by example and show the rest of the country how a blue city can fix its problems and be a vibrant, affordable, and low-carbon place to live. This starts with simply allowing people to build more sustainable housing in neighborhoods they want to live in.

Michael Gillenwater

Michael Gillenwater is executive director of the Greenhouse Gas Management Institute. An international expert in greenhouse gas emissions mitigation, he has repeatedly served as lead author for the IPCC, contributed to its 2007 Nobel Peace Prize, and negotiated for the U.S. at United Nations climate change treaty meetings. He holds a doctorate from Princeton University as well as graduate degrees from MIT and the University of Sussex. Michael lives with his extended family in Seattle and volunteers to improve housing policy in the Pacific Northwest in his free time.