Yesterday the White House released a document called the “Housing Development Toolkit” that stirred major excitement among housing advocates and Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY) crowd. President Obama is proposing $300 million dollars in his 2017 Housing and Urban Development (HUD) budget for “Local Housing Policy Grants to help facilitate those cities’ success in modernizing their housing regulatory approaches.” The toolkit lays out ways to ramp up housing production, including loosening zoning restrictions, streamlining permitting processes, and reducing parking minimums. It also supports inclusionary zoning to facilitate economic integration.

The Executive Summary begins with a succinct summary of recent land use history and how it relates to widening income inequality.

Over the past three decades, local barriers to housing development have intensified, particularly in the high-growth metropolitan areas increasingly fueling the national economy. The accumulation of such barriers–including zoning, other land use regulations, and lengthy development approval processes–has reduced the ability of many housing markets to respond to growing demand. The growing severity of undersupplied housing markets is jeopardizing housing affordability for working families, increasing income inequality by reducing less-skilled workers’ access to high-wage labor markets, and stifling GDP growth by driving labor migration away from the most productive regions. By modernizing their approaches to housing development regulation, states and localities can restrain unchecked housing cost growth, protect homeowners, and strengthen their economies.

President Obama delivered comments at the US Conference of Mayors in January that hinted at his interest in boosting housing options in cities: “We can work together to break down rules that stand in the way of building new housing and that keep families from moving to growing, dynamic cities.” The toolkit fleshes out that pledge and suggests responding with a suite of land use changes.

- Establishing by-right development

- Taxing vacant land or donate it to non-profit developers

- Streamlining or shortening permitting processes and timelines

- Eliminate off-street parking requirements

- Allowing accessory dwelling units (ADUs)

- Establishing density bonuses

- Enacting high-density and multifamily zoning

- Employing inclusionary zoning

- Establishing development tax or value capture incentives

- Using property tax abatements

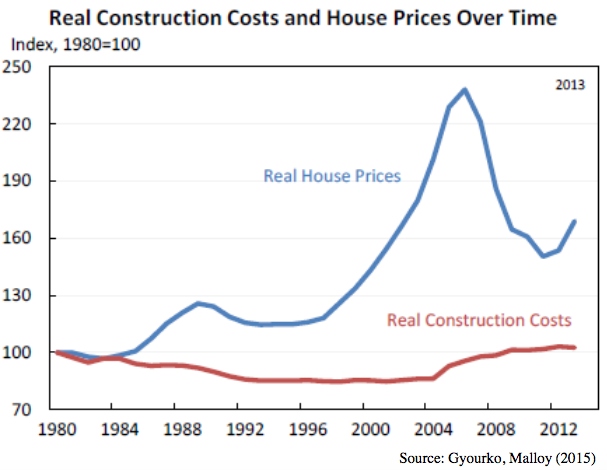

The toolkit cites research showing housing costs have increased much faster than construction costs:

An Expanding Problem

The scale of this problem goes beyond its poster child, San Francisco, and other noted high-cost large cities in California and the Northeast: “Growing, dynamic cities like Atlanta, Denver, and Nashville used to be able to tout housing affordability as a key asset–but now see rents rising above the reach of many working families. Inland cities have experienced some of the largest increases in rent in recent years, despite lacking the topological space constraints faced by coastal cities.”

Rising rents has translated to real hardship for low income Americans. “In just the last 10 years, the number of very low-income renters paying more than half their income for rent has increased by almost 2.5 million households, to 7.7 million nationwide, in part because barriers to housing development are limiting housing supply.”

Dealing With Displacement

The toolkit points out that limited housing supply region-wide often funnels development into low-income communities of color “causing displacement and concerns of gentrification in those neighborhoods, raising market rents within neighborhoods experiencing rapid changes while failing to reduce housing cost growth region-wide.” [bolding original] Lowering barriers region-wide would lead to more equitable distribution, decrease displacement, and help communities of color retain their cultural character and sense of place.

Integrating With Better Transportation

The toolkit makes the critical connection between better land use and more efficient, lower emission transportation.

Smart housing regulation optimizes transportation system use, reduces commute times, and increases use of public transit, biking and walking. A preponderance of a metro area’s commuters living far from work in pursuit of affordable housing prevents infrastructure, including public transit, from being used efficiently and effectively. Smart housing regulation would close the gap between proximity and affordability. More residents with access to walking, biking and public transit options also means less congestion on the roads and overall reductions in traffic congestion, greenhouse gas emissions, and commute times.

Employ Inclusionary Zoning

The Urbanist also appreciates the toolkit’s shout out to inclusionary zoning which was a hard-fought key to the Grand Bargain negotiated by the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) committee: “Inclusionary zoning laws that facilitate working families accessing high-opportunity neighborhoods are effective in reducing segregation and improving educational outcomes for students in low-income families.” The toolkit cited some local successes with the policy:

As of 2014, such policies had been implemented by nearly 500 local jurisdictions in 27 states and the District of Columbia. Not only have such policies expanded the availability of affordable housing while allowing for new development that otherwise might have been locally opposed, they have also been shown to improve educational outcomes for low-income children gaining access to higher-performing schools.

Seattle’s MFTE Cited As A Value Capture Strategy

The toolkit’s ninth policy recommendation is to establish value capture incentives and the example cited was Seattle’s program.

The Seattle Multifamily Tax Exemption program, which was modified and renewed in 2015, provides property owners and developers a tax exemption on new multifamily buildings that set aside 20-25% of the homes as income- and rent-restricted for 12 years; currently approximately 130 properties in Seattle are participating in the program and an additional 90 are expected to begin leasing MFTE units between 2016 and 2018.

Microhousing Mention

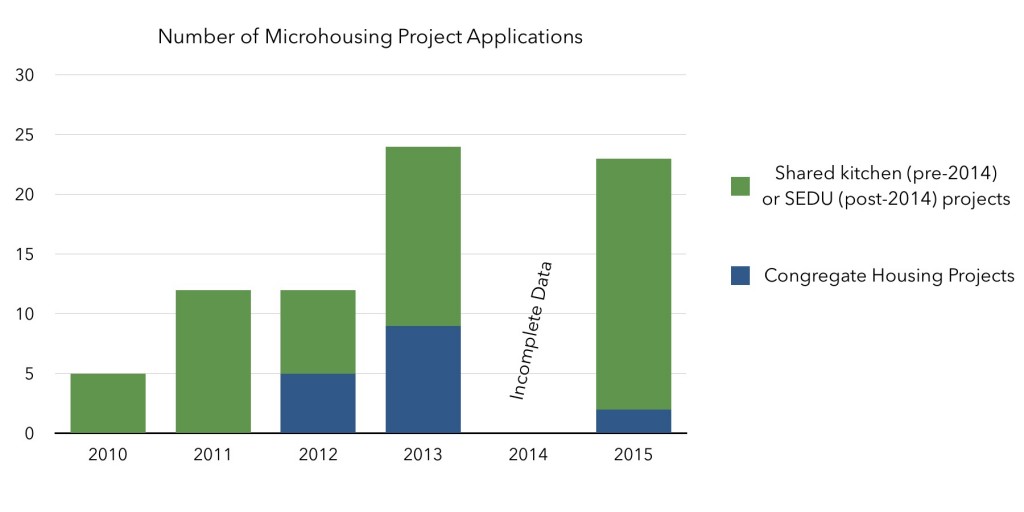

Seattle also got a mention for its leading the way on microhousing: “In Seattle, the city has nearly 800 micro-units with another 1,500 or so in the pipeline–more than any other city–yet, changes to the zoning code will disallow future approvals of such housing.” The last clause suggests Seattle’s zoning now blocks microhousing which is only partially true. The new rules stipulate micro-units are at least 220 square feet and have in-unit kitchens, creating a new “Small Efficiency Dwelling Unit” (SEDU) category from 220 to 300 square feet. The smaller congregate-style units with shared kitchen units are indeed blocked, but plenty of SEDU units are still moving forward: including this Nesbit project, N 50th St project in Wallingford, this Roosevelt project, this other Roosevelt project at N 66th St, and another kitty corner. Ethan Phelps-Goodman had an excellent microhousing analysis of building trends before and after the 2014 restrictions. Showing a similar amount of units were being produced.

So, proclamations that micro-housing is dead are misleading; although, the smallest congregate housing units that often rented for the lowest amount are indeed prohibited currently. And we agree with architect David Neiman that the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) 70-7 rule is capriciously restricting the market by setting an additional requirement for open space. Let’s not invent new hurdles for micro-housing providers with every passing year. Make a fair rule and stick to it. Micro-housing is a Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) recommendation after all: “MF8. Remove recently created barriers to the creation of congregate micro-housing.”

In Conclusion

So time will tell if Obama’s $300 million to fund a rewriting of housing policy across this nation will make it though Congressional sausage making. Hopefully it does, but, either way, we as housing advocates welcome the rhetorical shift emphasizing the need for cities to pick up the pace of multifamily housing production and focus policy on affordability and equity rather than obstruction and ever-lengthening process. It helps to have friends in high places. So thanks, Obama.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.