In the final weeks of 2019, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) was facing down the fact that the city would end the year with the most traffic fatalities in more than a decade. The department’s Vision Zero coordinator appeared in front of a city council committee that December along with SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe to talk about the immediate actions that the city was taking to reverse that worrying trend in 2020. Among them were “emphasis patrols” in conjunction with the Seattle Police Department.

Bradley Topol, the coordinator of the Vision Zero program at that time, described the patrols as targeting “specific behaviors that we know are some of our largest contributing factors to collisions and fatalities across the city, such as impairment, distractions, speeding, and failure to stop for pedestrians” along streets with high collision rates. The department would also be utilizing plainclothes police officers to conduct awareness campaigns for drivers regarding yielding at crosswalks. SDOT has coordinated such patrols for many years, notably in 2013 as part of the city’s pre-Vision Zero “Be Super Safe” campaign.

But in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic combined with that summer’s protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder prompted the department to reassess the role of relying on police enforcement as a go-to tool. Those emphasis patrols stopped. Director Zimbabwe, appearing back at the city council in 2021, spoke to the shift in the department’s thinking.

“It’s time to daylight the uncomfortable reality that relying on an enforcement-heavy approach in transportation can also lead to disproportionate financial impact, injury, and death for Black and brown community members across our city and across the country,” he told city councilmembers less than two years after the same team had been touting its police enforcement strategy.

Allison Schwartz, who took over as Vision Zero coordinator in August of 2020, has been a key part of that shift taking place. She notes that the department is still wrestling with these issues, but talks about the pause in enforcement as a very intentional choice driven by the department’s reassessment of its race and social justice goals.

“We’re kind of in this in-between place,” Schwartz said. “We’ve tended to lean on engineering, enforcement, education, those e’s, without really questioning to what degree they’re helping us get closer to Vision Zero.”

A lack of results was also a factor.

“Anyone, any organization, when you’re not getting closer to achieving your goal, you need to pause and examine your approach,” Schwartz told me. “We really want to move more toward a Safe System approach that really emphasizes the responsibility of a city to design and operate our transportation system in a way that acknowledges and plans for both human error and human frailty.”

The Safe Systems approach de-emphasizes the role of the individual in improving traffic safety, and looks at how the system can be improved to both prevent traffic collisions and make them less severe when they do occur. Despite Washington being the first state in the country to adopt a Target Zero goal of zero traffic deaths in 2000, modeled on countries that have adopted the Safe Systems approach, agencies like the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) have only recently begun to fully embrace the approach.

Late last year, the City released the latest version of its Safe Routes to Schools action plan. An update to a plan released in 2015, on the heels of the creation of the Vision Zero program, the document no longer includes enforcement as one of its pillars. “Throughout 2020 and into 2021, staff across SDOT have engaged in conversations around the role of enforcement and policing in transportation. Using a racial equity toolkit framework and led by our Vision Zero team, SDOT is examining the traditional engineering, education, and enforcement approach we’ve relied on,” the plan states. “Together, we are moving toward a safe systems approach that encompasses a more holistic understanding of what it means to feel safe while traveling on city streets.”

Schwartz acknowledges that SPD staffing capacity was a factor in deciding to put emphasis patrols on hold. But also sees the decision as being grounded in the city’s own goals around racial justice. She pointed to steps that are being taken by Seattle’s Office of the Inspector General, one of SPD’s oversight bodies, around the role of police stops and traffic safety enforcement. Paul Kiefer of PubliCola reported last month that there is clear resistance to that idea of phasing out lower level traffic stops within the department, with interim Chief Diaz delaying his expected recommendations.

Increased enforcement is a very common traffic safety intervention across Washington state. The Washington Traffic Safety Commission, which manages the state Target Zero plan, allocates millions of dollars per year in safety grants to local police departments and the Washington State Patrol to conduct “high visibility enforcement.” Between 2016 and 2020, more than 200 local police and sheriff’s departments received funding specifically to enforce traffic laws in ways that were designed to be noticed by the general public. Only a tiny fraction of those same cities have received traffic safety grants to improve the design of roadways.

With this shift away from police enforcement, the Seattle Vision Zero team is turning its attention to the programs that it says are the most effective: focusing on improving high crash corridors— since half of the serious and fatal crashes in Seattle occur on just 11% of the city’s street network— and scaling up impactful changes like leading pedestrian intervals, where pedestrians get an extra few seconds before a traffic light turns green to enter an intersection, and hardened center lines. Approximately 400 intersections have been outfitted with leading intervals in the city, and SDOT’s data shows that serious and fatal injuries have been reduced by 35% at intersections with them.

The education “e” is not being thrown out of SDOT’s toolkit, however. This year, the department will be working with a consultant to develop a campaign called Safe and Slow Seattle, which will have two prongs: increasing awareness about Seattle’s citywide speed limit reductions, and increasing awareness of the fact that all intersections are legal crosswalks. That campaign is funded by a Traffic Safety Commission grant as well.

Unfortunately, the situation on the ground is not improving while this shift takes place. 2021 will replace 2019 as the most deadly year on Seattle’s streets since 2006, with a preliminary tally of 31 fatalities. Nineteen of those lives lost belonged to people who were walking. Nine of the 31 fatal crashes within the city limits occurred on state controlled highways, where additional hurdles exist to making the types of comprehensive changes that the city has implemented on other corridors.

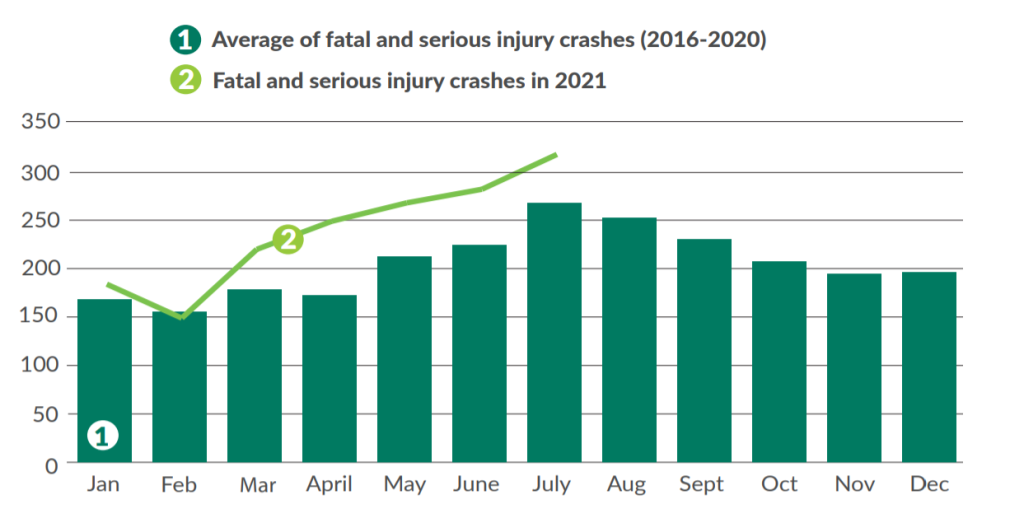

The uptick in fatalities mirrors a statewide trend. WSDOT data through the first half of 2021 shows that in all but one month, fatal and serious injury crashes were markedly higher than an average of the previous five years, with the Washington State Patrol confirming that August 2021 was the deadliest month on Washington roads since 1997.

Seattle does not operate in a vacuum, and if either the state or the city are going to make improvements toward their mutual but increasingly unlikely goal of eliminating traffic deaths by 2030, their policies will need to work hand-in-hand. But as Seattle’s Vision Zero team takes a hard look at what is working and what is not, it remains to be seen whether the state will follow. What is clear is that the current systems aren’t working, and Seattle is trying to lead the way.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.