This month, Seattle has hosted some of its biggest events of the summer and local pundits are busy writing the first draft of history. From Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game week to Taylor Swift’s massive concert pairing, a ton of people visited Seattle. Some are ready to say it was the kick in the butt the downtown economy needed, including Beth Knox, CEO and president of the Seattle Sports Commission.

“The week of activities, we think, was a really great success. We saw it as a tipping point for revitalization in downtown Seattle,” Knox told KING 5, adding that Seattle most likely reached its goal of $50 million in revenue generated, with more than 100,000 people in attendance.

But did these events provide a jolt to the economic engine that will be sustained into the future? And did that jolt rev up all neighborhood engines equally? Those are harder to questions to answer with reasons for doubt.

What’s clear is that since the summer event season can only last so long, Seattle would be wise to focus on sustained efforts that carry economic activity well into the wet gray of winter and the doldrums between big sports events — things like adding more residents in the downtown core and making it easier to get around with transit improvements and safe facilities for walking, rolling, and biking — and then enticements to linger with pedestrianized streets packed with storefronts supporting unique local businesses.

It’s hard to argue that the economic benefits of July’s event binge were shared equally, and they could constitute a short-lived sugar high if the City doesn’t do more to sustain and distribute that added activity. Several businessowners in Pioneer Square and the Chinatown-International District said they missed out on the All Star Game boom, with business flat rather than booming in that time period. They pointed out the guidance from local leaders for tourists to avoid the Third Avenue corridor and stick close to the Waterfront which likely sapped foot traffic and business from the area and neighboring districts in Chinatown and Pioneer Square outside the so-called “green zone.”

While the region’s newspaper of record and the director of the Seattle Department of Transportation were advising tourists to avoid the city’s main bus artery due to crime and disorder fears, Sound Transit still managed to break previous light rail ridership records during All-Star week.

There are two main areas along Third where poor people hang out. One is around Pine Street and has been a drug hot spot for decades. The other is in Pioneer Square near a lot of low-income housing. Sad to see the city promote the idea that downtown is squalid.

— Erica C. Barnett (ericacbarnett.bsky.social) (@ericacbarnett) July 8, 2023

“We’re still crunching the numbers, but early reports suggest that the previous ridership record has been broken on at least nine days in July alone,” Sound Transit’s Kate Dieda wrote in a July 28 post. “July has been a record-breaking month for 1 Line ridership, with the All-Star Game and the twin Taylor Swift concerts coming on top of a very busy summer calendar in Seattle.”

The ridership bump on King County Metro buses likely wasn’t as dramatic since its bus operator and mechanic shortage has cut into service levels and the campaign to detour tourists around Third pushed them farther from bus routes. A Metro spokesperson said the agency is still tallying the numbers.

In search of solutions rather than quick fixes for homelessness and crime

Even as leaders urged guests to avoid Third Avenue due to the unsightly poverty and crime they expected them to find there, the Harrell administration did make an effort to clear out the poor and potentially disorderly element out of downtown. As Shaun Scott wrote in The Stranger, the Mayor’s binge of homeless camp sweeps (or camp “removal” if you prefer the more sanitized version) represented an ugly underbelly to the week of All-Star revelry — an attempt to gussy up for the national crowds after repeated campaigns to end homelessness have come up short.

“As Seattleites, we should ask ourselves: What makes a great city? The rush to look good before tourists arrive, or the character to be good when the world isn’t watching? Big arenas and entertainment, or social housing and shelter for all? — Bread or circuses?” Scott wrote. “By betting on itself, Seattle can be the city the world thinks it is. Sweeping up for guests is a blood sport we’ve never won.”

While homeless sweeps can clear the visible problem out of a particular neighborhood temporarily, until the underlying causes are addressed (with housing affordability clearly the primary driver), homeless camps will roar back and continue jumping from neighborhood to neighborhood in a never-ending cycle. This game of whack-a-mole is expensive to run and it’s not conducive for long-term economic recovery.

By steadily harping on downtown crime, disorder, homelessness, and “open air drug markets,” the centrist political machine has won elections, but it also has created an image problem for downtown that counteracts its own goals of recovery. Nobody’s saying downtown is a picnic right now, but the incredible amount of air time given to stories of crime and disorder versus literally anything else happening downtown is creating a negative feedback loop that scares away the foot traffic boosters are so keen to attract.

And ironically, since the solutions offered are so short-term (think: sweeps and emphasis patrols), the problem never retreats enough for the next round of political campaigning to not play the same card and repeat the cycle. Whether downtown disorder can stop being a political punching bag long enough to effectively carry out a downtown branding overhaul — let alone a lasting solution — remains to be seen.

Saving South Lake Union from itself

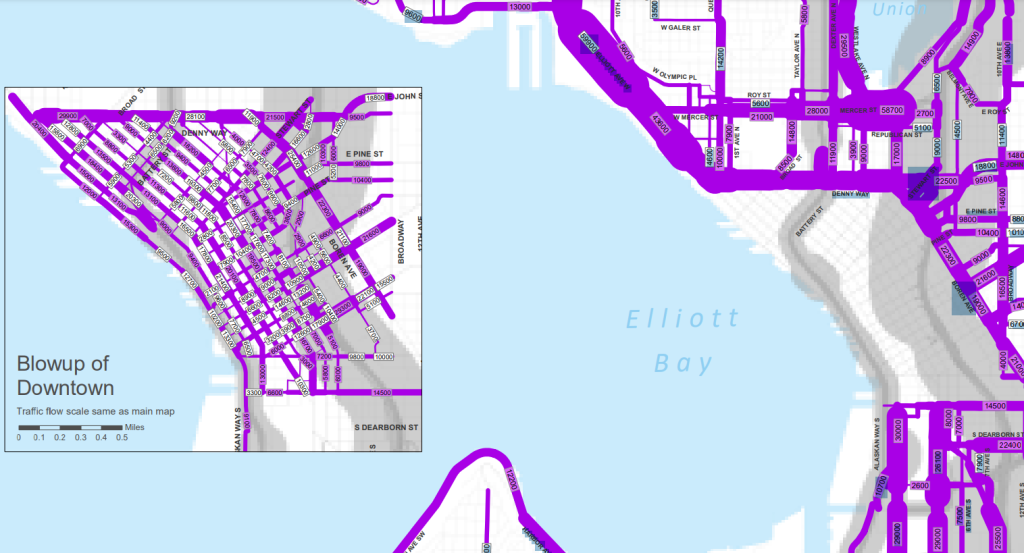

Even as some boosters are ready to declare downtown is back, they also warn that the recovery is incredibly fragile. That worry has dominated the debate about where to build the new Ballard Link light rail line when it passes through downtown. When it comes to Denny Station options, it has meant fierce resistance from corporate leaders to options that require long closures of Westlake Avenue, even though the street carries only a few thousand daily vehicles through the section in question and reasonable transit detour options exist.

“We continue to strongly oppose proposals that would result in closing Westlake Avenue for half a decade or longer,” an Amazon spokesperson testified Thursday ahead of the Sound Transit Board’s big vote. “Since May, we have worked hard to get current employee attendance back to pre-pandemic levels, which I would remind you that many members of this board called for and applauded. This recovery is important and is one that your voters want to see. Between May 2022 and 2023, we have seen an 82% increase in foot traffic. We are doing our part to bring downtown back and we hope this board will do theirs.”

Amazon’s distaste for the Westlake street closure was so strong, they even appeared willing to jettison South Lake Union’s Harrison station, which serves the other side of their campus and was expected to be one attract more than 10,000 daily riders, to do it. That’s what their preferred “Shifted West” alternative would do. In what world is canceling a light rail station next to dense urban neighborhoods that were promised them (and made development plans based on them) good for long-term economic development?

Pushback from Amazon and others led Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell to pivot to Shifted West, then back to Westlake, and then ultimately to a new unvetted Shifted North alternative that costs approximately $170 million more than the existing Westlake Avenue option south of Denny Way. The Shifted North option does reduce street closures by acquiring a Vulcan property for approximately $200 million to use for construction staging, which clears the way for putting decking over the station pit construction along Westlake Avenue, according to Sound Transit.

The question before policymakers now is whether that $170 million is a worthy investment. Are the impacts of the closure of Westlake Avenue that could last four years — unless Sound Transit finds a way to do decking to the south as well — so severe that we should invest $170 million mitigating them and end ups scrunching the station closer together with the neighboring South Lake Union Station planned at Harrison Street and 7th Street about a quarter mile away? Is it worth doing another Draft Environmental Impact Statement delaying the project more in order to get those new options into play?

So far, Sound Transit boardmembers have answered ‘yes’ to all of these questions and delayed the project accordingly, driving up its cost considerably. This could well end up being counterproductive as the arrival of Ballard Link could provide an economic jolt a magnitude larger than any old car street ever could.

Dancing under these questions is the fundamental question whether the downtown recovery is so fragile that four years of street closures will do the whole thing in? Several stakeholders said they thought South Lake Union would never recover from such a thing, which makes me think the neighborhood is so fragile it might blow over in a stiff wind. Better pack it up now and put our billion-dollar infrastructure investments in a neighborhood that isn’t daunted by a detour and brought to an existential crisis by some orange cones.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.