General Manager Michelle Allison said King County Metro is charting a path to growth, but recovery will take time.

Last month King County Metro took the unusual step of announcing its fall service change in the spring. The reason: The agency is cutting service by 4% due to a labor shortage and wanted to soften the blow and daylight its plans to staff up.

Metro General Manager Michelle Allison delivered the news to the King County Council at a transit committee meeting on May 16 and received a preliminary blessing. Councilmembers were swayed by the argument that the unreliability caused by overpromising and underdelivering service was hurting riders more than lower planned service levels would. Allison pledged a comprehensive recruitment strategy to right the ship.

King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci sought greater detail on the recruitment push and asked for Metro to provide regular updates on their progress.

Allison said Metro is short about 150 full-time bus drivers to deliver planned service (before the 4% cut). The agency is also down a significant number of mechanics, which makes it hard to keep its fleet of buses in service. The 150 estimate suggests some modest improvement from April, when the shortage was larger.

“As of April, Metro has 2,484 transit operators, including 571 part-time bus drivers and 1,913 full-time bus drivers. An estimated 172 additional full-time equivalent, or a combination of 113 full-time operators and 99 part-time operators, are needed for current service levels. Service levels will be aligned with estimated available workforce in September,” the agency said in May 11 announcement.

As a result of the worker shortage, Metro said it was delivering between 95% and 97% of scheduled service. Last-minute cancelations of scheduled buses mean longer waits at the bus stop and frustrated riders, which can sour them to the whole enterprise. Unreliable, less frequent service has meant a slow recovery in ridership after the pandemic.

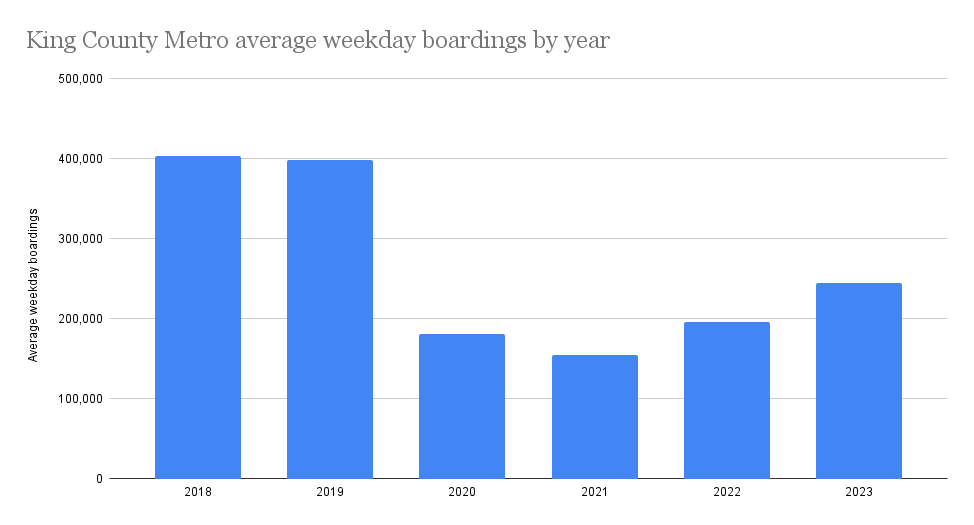

Metro reported 251,368 average daily weekday boardings in April, which was up almost 15% over the previous year, but still well short of the 400,000 daily ridership mark the agency routinely hit pre-pandemic. Factoring in canceled trips, Metro is delivering about 90% of the bus service it did in 2019 and getting just over 60% of the ridership.

Recently, The Urbanist sat down with Allison, who was promoted to Metro’s top post following the retirement of her predecessor Terry White at the end of 2022, to hear more about the agency’s recovery plan. Allison was optimistic recruitment numbers were trending in the right direction.

“Our recruitment numbers are definitely trending in the right direction. And so I think I can speak a little bit in 2022, we have already hired 1.8 times the number of placements in 2021. So just a little context, in 2022, we placed over 1,300 employees into new positions. This isn’t just operators, but think of that on the whole for what Metro needs across the agency. We are seeing higher numbers of people in the pipeline and coming into the agency; we just have a really big need.”

While Allison stopped short of setting a timeline for eclipsing pre-pandemic service levels – like LA Metro recently did after recruiting 1,000 operators in a year – she did emphasize charting growth is what the agency is after.

“I can’t give you a date,” she said. “What I can say is we’re working hard to make our September service and our workforce match. And then we’ll work hard after that moment in time to get to growth from the suspended service hours and invest in that.”

“This is a marathon, not a sprint”

Allison laid out a three-pronged labor strategy to recruit, train, and retain the workforce the agency needs. That has started with speeding up the process of applying and getting into a training class and doubling the size of those training classes to seek to meet the need for additional operators.

“This is a marathon; this is not a sprint,” Allison said. “None of this is going to be solved overnight. But Metro needs all of these things to work so that we have that really solid and secure pipeline process and understanding of what our employees need and we’re giving it to them so that we can then grow. Our job is not just to deliver the service that we have now, we want to get to growth. And that’s where we need all of these elements to be successful.”

But the pandemic has been a huge hurdle for transit agencies to overcome. Already facing an aging workforce, transit agencies saw a wave of retirements and career changes out of the profession during the pandemic, and also furthered that trend by laying off workers and slashing service due to lower demand.

Allison did not set a date of when the agency could return to pre-pandemic service levels, but she did argue the crisis had helped the agency hone in a better strategy for recruiting and retaining employees.

“In conversations, there is not a single transit agency who feels like they’re stable enough where this isn’t an issue that’s on their mind,” she said. “So I see it in two things. One is the incredibly destabilizing effect of the pandemic, where we just lost a whole bunch of workforce at one time, for all the reasons that we did. Recovery from that takes a long time, and it will include those environmental conditions of where you live, the dollars that it pays you for the cost of living for your location…”

Pending raises via active labor negotiations

Metro is the midst of negotiating a new contract with the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 587 which represents its operators and mechanics. The pay bump and other incentives worked into that deal could prove crucial to boosting the workforce.

“People are wanting different things from their employers these days, economics is one. But there’s a lot of other things that make a good employer, the investment in the employee, the opportunity to see growth in a timely manner for someone’s career, right, there’s a lot of other things from an individual experience,” Allison said.

As Allison presented to the King County Council, transportation committee chair Rod Dembowski voiced support for the 4% cut to service to ensure higher reliability and for increasing compensation and offering hiring and retention bonuses. He noted the County had deployed large bonuses to buoy the Department of Corrections.

“I want to give a nudge of support to the executive branch as it bargains with ATU 587 and our other represented workforces, to the extent that is helpful, monetary compensation in achieving those recruiting goals that you would have my support, and I suspect broad support here from the council,” Dembowski said.

While Seattle Police Department hiring bonuses approved last year have failed so far to achieve their intended up of staffing up the department, it’s possible that the market for operators will behave differently. Allison said the agency is looking at attracting workers through a variety of means and expecting higher wages to be more persuasive that one-time bonuses.

“I think, from listening to transit agencies across the country, the verdict’s still out on what the right combination of economic incentives are,” Allison said. “We know just from a human perspective, that if you have certainty in a raise and your base salary is what is exciting to you, one-time dollars are good… but you really want to see the stability of your salary, right? That is really important… I don’t want to speak too, specifically, because we are in active negotiations. But there is a really solid economic proposal that has many different aspects, salary raises, and different one-time funding, all of that is on the table.”

Bus driving as an essential community-serving part of the green economy

Metro is also working to hone its pitch as offering workers a great career arc, being an integral part of the green economy, and being a great place to work.

“We need to reintroduce transit to a new generation of workforce. If you talk to folks – and I have been for a long time – who’ve worked in the transit industry, especially operators 40 years ago, right? They saw themselves as this knitted together necessary part: postal worker, police officer, fireman, bus operator, right? There was this real identity and pride in that role and in the service they provided, we need to reintroduce Metro back to the communities and available workforce with that same sort of pride.”

Allison called it “generational work” to pitch transit careers to a new generation and instill that professional pride.

“We do do that at Metro, but we need to be more proactive about it,” Allison said. “So we can invite that next generation and they can see the value in the benefit of a stable job at the County: great benefits, great retirement, we’ve got great pay, and you’re doing something mission-oriented. I think that a new introduction – we have a lot of competition in this tech space, here, we’ve got a lot of other things that could be really attractive to a new generation – but really showing the benefit of working with and for your community.”

Metro wants to reach kids before their senior year of high school to pitch them on a trade that does not require expensive college or training. Rather than going into a mountain of college debt, young adults could enter a transit trade and start putting money away.

“We can really reintroduce how cool it is to be part of the trades industry and how you can enter and start getting paid immediately,” Allison said. “You can sort of bypass some of the educational requirements, if that fits you and the choices you want to make for your life. So I think it’s all things right. It’s how we talk about it. It’s where we go to invite people in. You have to reach a new generation a lot earlier than their senior year of high school, if you’re going to ask them to make a choice about their future. So it’s outreach, it’s engagement, it’s marketing. It’s how we make these jobs available for folks. It’s all of those components.”

Training process improvements

While the 10,000-foot view could prove important to solving Metro’s staffing woes long-term, in the immediate term the agency is facing practical hurdles and bottlenecks that limit its ability to increase its ranks. The agency is seeking to more seamlessly funnel people into training and increase passing rates for the courses, which include obtaining a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) and learning safety regulations since the field is heavily regulated by the government as a safety-sensitive profession.

“The next cog that we need to work on, that we are working on, is our training,” Allison said. “If you can get a whole bunch of people in, but then they’re all stalled in the process because of training, we’v got to work on that. So we’ve doubled our training size, we’re looking at different ways where people are more successful or less successful in our training program, so we can really pinpoint where we need more dedicated resources so our passing rates are higher. So there’s a language access issue. There’s a CDL testing component. So those are other things in our training profile that we’re trying to see if we can continue to expand that pipeline. Doubling, it’s a great start; we need to do a little bit more.”

That training pipeline appeared to suffer in the pandemic, both in terms of applicants and how efficiently Metro was moving people through the hiring and training process. For example, one applicant reported applying in January and being offered an interview slot in May, four months later. In the interim period, that applicant moved on and found another job, which will likely be a common story if applicants are asked to be in a holding pattern for months at a time.

Making it into a training class does not necessarily mean applicants have smooth sailing. Metro’s training course lasts the better part of a month and during this time applicants earn a lower training wage and are generally not granted time off. Transit workers also face stricter drug regulations than most other jobs.

Possibility of marijuana test reform

Even though marijuana has been legalized in Washington State for over a decade, due to federal regulations, operators are tested for it during their drug tests. This restriction further thins the pool of available workforce since 15% of Washingtonian adults reported marijuana use in the past 30 days, according to the State Department of Health, and 56% reported use at some point in their lives.

The urine tests that have been federally required can turn up positive tests for marijuana weeks after use, which means operators or mechanics cannot even imbibe on their days off or vacation time without risking a failed test that could cost them their job.

Last fall, the Biden administration announced some reforms around cannabis policy, but stopped short of lessening requirements on the transportation sector, which drew criticism. In a significant pivot, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) issued guidance in May that a saliva test would be acceptable as of June 1, 2023.

The new guidance from the DOT did note one remaining hurdle: “In order for an employer to implement oral fluid testing under the Department’s regulation, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will need to certify at least two laboratories for oral fluid testing, which has not yet been done.”

Allison indicated Metro was still operating under the assumption urine tests would be required.

“I’m not sure that there’s a huge movement from the Feds to relax the safety sensitive condition for positions that require it,” Allison said. “And that would include our operators. So I’m not sure we’re there yet.”

However, once certified laboratories are available, it would appear Metro could make the switch and further expand its pool of qualified and interested applicants while providing a less invasive testing option for existing employees.

Getting to service growth and Metro Connects vision

Metro has bold plans for the future, such as its Metro Connects vision that would take its RapidRide enhanced bus system from A to H Line (skipping the G Line until its expected belated debut next year) and beyond. However, the reality has been a slow rollout following the first A to F burst. The H Line launched in March was the first new RapidRide line in nine years.

The Move Seattle transportation levy passed in 2015 promised seven new “RapidRide+” lines, but, shortly after taking office, Mayor Jenny Durkan canceled three of these RapidRide conversions (Routes 40, 44, and 48) due in large part to fewer grants than anticipated from the Federal Transit Administration that was controlled by Trump Republicans rather than more transit-friendly Democrats. The onset of the pandemic added further strain to transit project timelines regionwide and nationwide and led to the RapidRide conversion of Route 7 also being shelved, as well as the RapidRide K Line in Kirkland and Bellevue. The G Line is expected next year, followed by the I Line serving the Kent Valley in 2025, and Eastlake’s J Line circa 2027, but, after that, no imminent and funded plans for RapidRide expansion are on the horizon.

Thus, between the operator shortage and the lack of dedicated funding, the path is unclear for filling out the RapidRide alphabet as envisioned – let alone boosting transit frequencies on the workhorse buses that the agency already operates under its existing branding. Allison demurred when asked if Metro would be ready to significantly boost service in 2025 if voters passed a bus funding measure in 2024 (a presidential year that would appear an opportune time to do so).

“The best part about the question is the underlying motivator, which is everyone wants us to have more. Our cities want more transit. Our riders want more service. Our policymakers want more of the thing we’re delivering,” Allison said. “So that timeline is really important. 2024 feels really soon, right. But this is also not a conversation I get to have alone. This is definitely a discussion that includes the policymakers who set that course we are on. We’re just as eager as anyone to get a funded Metro Connects, and to get our ability to provide that service as soon as possible. But I certainly can’t provide a prediction on a date right now.”

Nonetheless, RapidRide lines are the backbone of Metro’s planned bus network, and one of the more exciting additions for riders and general managers alike. Higher transit frequencies and speeding up service are widely acknowledged among the best ways to attract and retain riders.

“So what gets me most excited is that we have the right people to take us into the next phase. It is programs like the RapidRide H Line. Look at what that does: that investment in that neighborhood that has historically been incredibly underserved just got an investment and an infrastructure boost, right,” Allison said. “That is an incredibly exciting program to see launch. And to get more of them in the queue is really exciting.”

Whether a part of RapidRide rebranding or not, Metro could invest in capital improvements that speed up service and squeeze more out of available service hours, such as bus lanes and spot improvements like transit signal priority and queue jumps, but it’s not clear that local DOT partners that control the street space are jumping up and down at the opportunity. Metro maintains a prioritized list of spot improvements and Allison said these capital upgrades are “on the table” but did not point to anything specifically in the works.

Allison also gave a nod to Metro’s microtransit program, which was recently reorganized and rebranded as Metro Flex and covers some of the hard-to-serve areas of the county.

“Little less talked about, but I think also exciting for the moment that we’re in now is our Metro Flex, that has a unique and kind of niche and smaller part of our system. But as we are still working to develop on that larger Metro Connects vision, how can we continue to connect communities together in ways that use mobility as an option, so they stay in the Metro community and they stay invested in and support it, and they think Metro Flex is an important part of that.”

With a little helpful prodding from Balducci, Metro will be returning to the County Council to offer progress reports on its recruitment push. Ensuring that medium- and long-term vision is achievable and will count on headcount headway being made, as will the more immediate goal of ensuring the next service change adds rather than subtracts from the system.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.