Bellevue is one step closer in planning its growth for the next 20 years after a series of City Council meetings on the topic in late July. By selecting a “Preferred Alternative” for study in the Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the city’s Comprehensive Plan Periodic Update, council has set the bounds for what levels of zoning and thus housing growth will be possible to enact in what areas. Although the selected alternative would increase the city’s capacity for housing by tens of thousands of units, a series of amendments to water down the proposal combined with concerning comments that tease forthcoming conflict points each chart a nebulous path forward for urbanists and housing advocates.

Many Neighborhood Centers near Frequent Transit will Retain Lowrise Zoning

On issues of disagreement, a predictable dichotomy emerged between progressive Councilmembers interested in exploring more density and conservatives concerned with “protecting” single-family neighborhoods. In comments opposing midrise housing in more of the city’s existing commercial areas, Deputy Mayor Jared Nieuwenhuis characterized such proposals as “density at any cost” thinking that isn’t “the reason people move, live, and work” in Bellevue.

“Our [single-family] neighborhoods are our treasure and we need to protect them,” Nieuwenhuis said.

The “protection” Nieuwenhuis wanted to offer would have upheld a Planning Commission decision to restrict mixed-use zoning in six neighborhood commercial centers at two to four stories. As The Urbanist reported in July, this decision was heavily influenced by Councilmember Jennifer Robertson, who intervened in the Commission’s process by directing staff to back off from their suggested proposal for densities between seven and 10 stories. Staff’s higher-density proposal came after several developers of neighborhood center parcels said that the originally-studied low-rise zoning would not provide enough of an upzone to incentivize residential redevelopment.

Ultimately, conservatives united behind a compromise proposal advanced by Robertson which would study lower midrise zoning designation (five to seven stories) only on neighborhood center parcels currently zoned for Community Business. This currently includes Kelsey Creek Shopping Center, Lakemont Village, and Lake Hills Village. Neighborhood centers currently zoned at the slightly smaller Neighborhood Business designation — Newport Hills, BelEast, and Northtowne Shopping Centers — would still be restricted to between two and four stories. Both BelEast and Northtowne will be a part of Bellevue’s frequent transit network after King County Metro realigns its bus network with the opening of the full East Link light rail line.

Bellevue Mayor Lynne Robinson was the crucial swing vote in a curious move that broke with her more progressive colleagues that were interested in studying midrise zoning across all neighborhood centers. After saying the previous week that she would be “open to studying all the possibilities for all the neighborhood centers” and coaxing staff to share that there were no disadvantages to merely studying higher densities through a midrise designation, Robinson reversed course and supported Robertson’s compromise proposal.

Although final zoning and precise amendments to the city’s land use code will come later in the process, this decision still matters because the Environmental Review process sets the scope of what changes are possible down the line. Because higher zoning designations could theoretically result in additional unforeseen environmental impacts, Bellevue leaders would be restricted from going any higher than zoning designations that were studied as part of either the Draft or Final EIS. Since only lowrise zoning for all neighborhood centers was studied across the three growth alternatives in Bellevue’s Draft EIS, midrise housing would only be allowed at the three centers for which it will be studied in the Final EIS — and even that final outcome is not guaranteed, as Council’s ultimate zoning decision could go even lower.

Heel-Dragging on Missing Middle

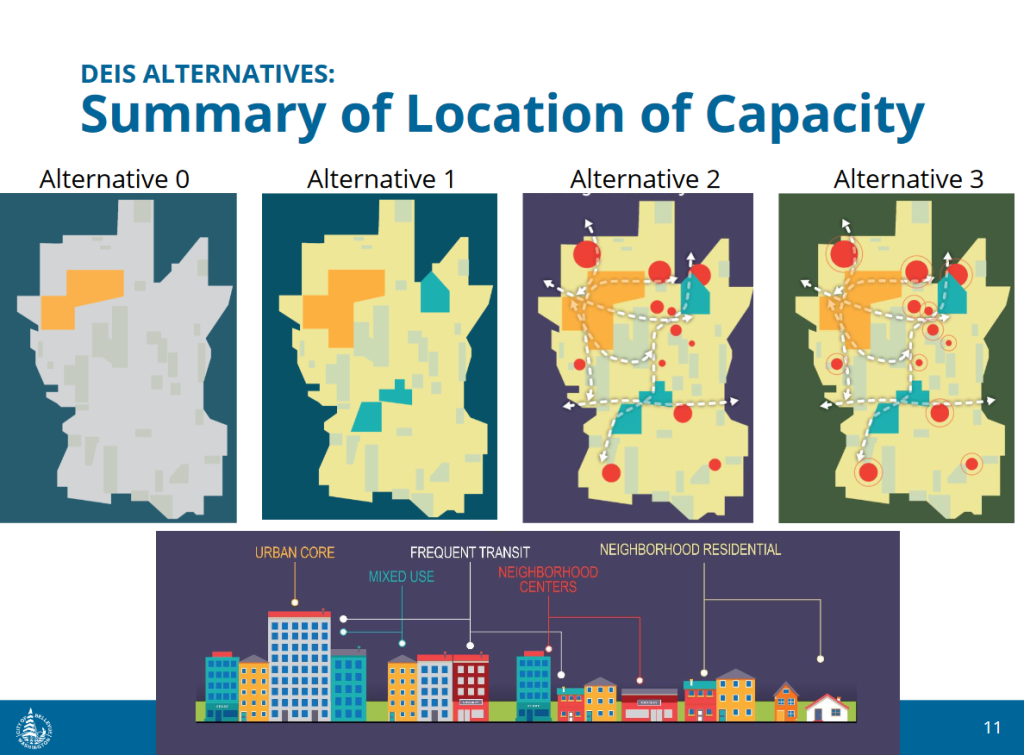

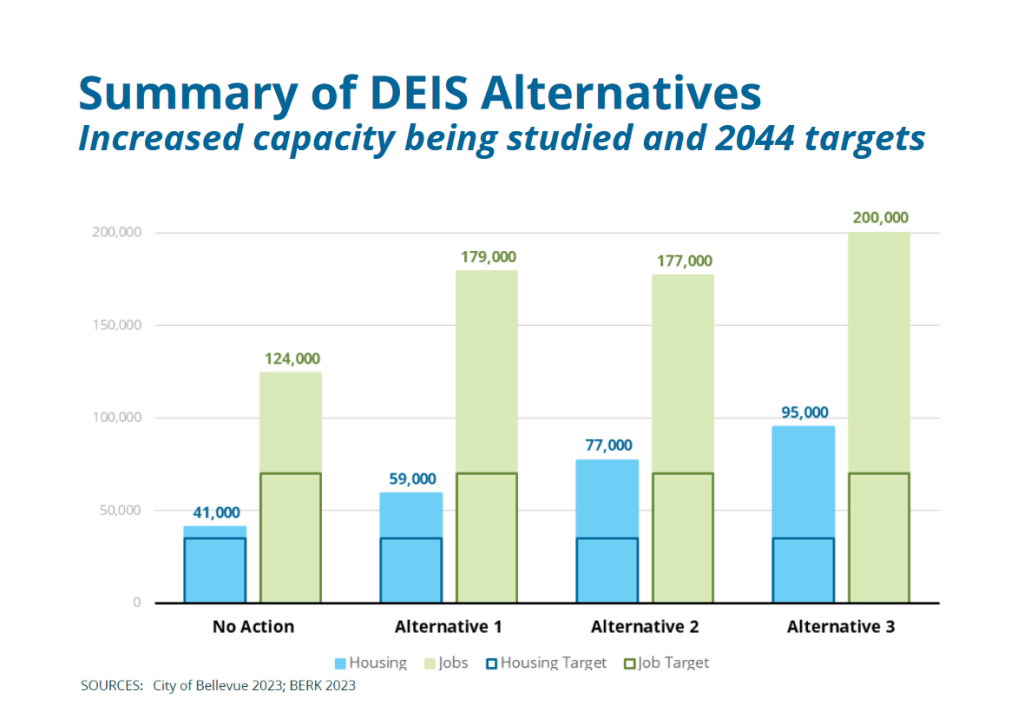

In the Draft EIS, three different alternatives were created to assess different levels of housing capacity, with Alternative 1 providing for the least amount of additional capacity and Alternative 3 for the most. The alternatives also differed at a conceptual level in how the growth would be distributed across Bellevue, with each subsequent alternative building off of the previous one.

For example, Alternative 1 would have continued the city’s existing approach of concentrating housing in existing growth neighborhoods (like Downtown, Wilburton, BelRed, Crossroads, and others). Alternative 2 would build upon this by expanding opportunities for housing growth in smaller shopping centers (i.e. the neighborhood centers) and in areas around frequent transit. As the boldest alternative with the largest capacity for additional growth, Alternative 3 went even further by extending growth opportunities to the areas around growth neighborhoods and commercial centers.

Modest upzones of these “Areas of Opportunity” would have allowed more types of missing middle housing near businesses and services that could serve people’s day-to-day needs, and including growth in such areas was a part of the Planning Commission’s original recommendation to Council. However, after significant pushback from residents and community leaders in Lochleven (a neighborhood adjacent to Downtown Bellevue), Council elected to remove all Areas of Opportunity from absorbing higher housing growth beyond what state law mandates. This means that, although all residential areas of Bellevue will have to comply with newly-passed HB 1110 and HB 1337, the city will go no farther even in areas where access to services would make further growth prudent.

“I wonder how necessary it is to do [Areas of Opportunity] given that we now have HB 1110 and HB 1337,” Mayor Robinson commented. “That’s a lot of change.”

Robinson continued by suggesting that the city could reassess the need for higher zoning in Areas of Opportunity in five years’ time by incorporating it as a separate land use amendment process. Council unified around this proposal, which would likely require a year-long process of additional staff time and community engagement at some indeterminate time in the future.

Councilmember Robertson went further by emphasizing early in the discussion that, because of recently-passed state laws and the city’s work near the East Main light rail station, the city technically would already have enough zoning capacity to accept its growth targets even if they took no further action. Although she clarified that this wasn’t an option she was seriously considering at this time, it does reveal a scarcity mindset that incorrectly equates available housing capacity as inevitable housing units. With Council believing that HB 1110 and HB 1337 alone will provide sufficient housing growth in residential areas, even those near growth centers, they seem poised to continue with a paradigm of only allowing any type of growth in certain predefined areas — unless they’re forced to do otherwise.

Promise in Wilburton, but Tree Codes Could Spell Trouble

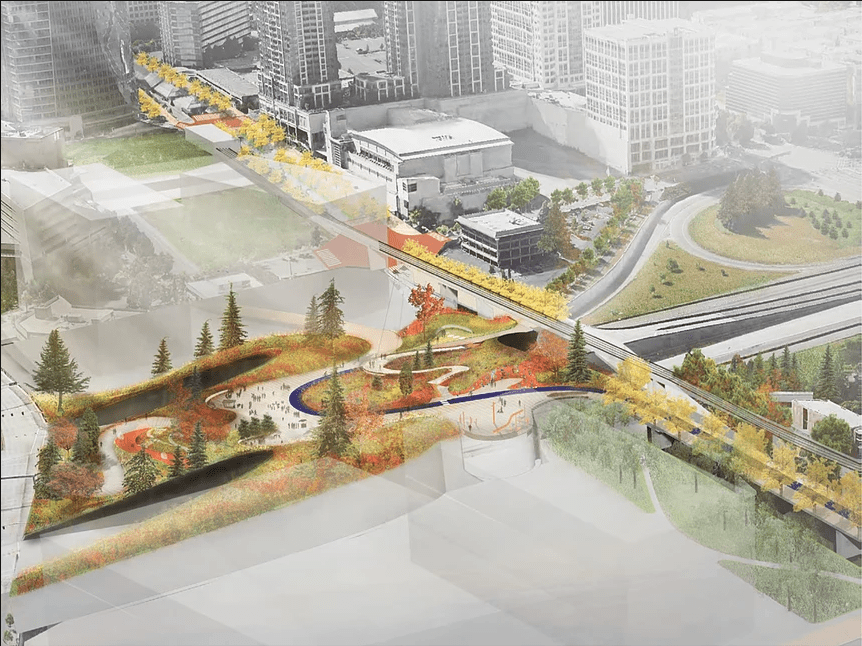

One of those predefined areas where there has been consensus to significantly increasing housing capacity is the Wilburton Commercial Area. Located around the future East Link light rail station, plans to upzone this area have existed for some time. Per Council direction, the Wilburton rezone is advancing in tandem with the Comp Plan Periodic Update but is expected to wrap up by the end of this year, as opposed to the citywide update that will last through summer 2024.

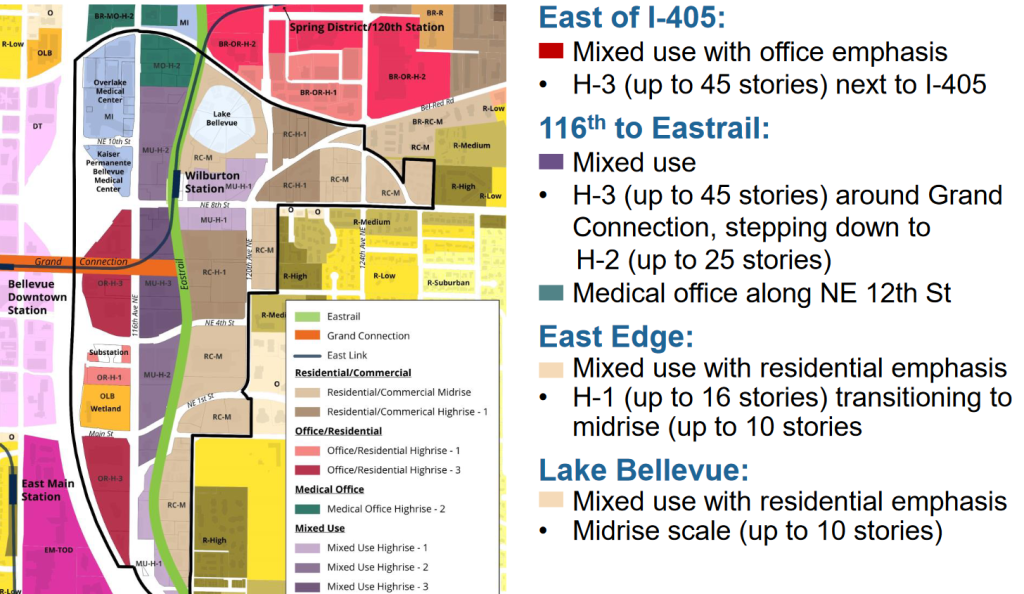

The Planning Commission’s recommended alternative for this neighborhood was pretty bold, and it remains so in its implementation by Council. When fully built out, the tallest buildings would be located near I-405 and centrally around the Grand Connection and Eastrail. Radiating away from there, buildings would gradually decrease in height to smaller sized towers and midrise buildings as one proceeds to the east of Eastrail.

Where conservatives noted their desire to minimize impacts to nearby single-family houses to the east of the commercial area, staff justified their proposal to assign lower heights east of Eastrail by noting midrise development would be more likely to create actually affordable housing within the neighborhood proper. Furthermore, the approved Preferred Alternative for Wilburton would allow for nearly as much housing capacity as what was originally proposed in the boldest alternative (over 14,000 housing units).

However, Council discussions around Wilburton were not devoid of cringe-worthy moments. Councilmember Conrad Lee, a presence on Bellevue City Council for 29 years and therefore a participant across several prior Periodic Updates, did not seem to understand the purpose of Council’s exercise in selecting a new option for further environmental study. Attempts from both Mayor Robinson and staff to answer questions about the process thus far employed in selecting alternatives were met with requests for more data, representing a lack of understanding that selecting a preferred alternative would direct staff to analyze a new proposed land use map to obtain the exact information he sought. The back and forth elicited visible frustration from the mayor, who called for a 10-minute recess that ended up lasting over 20. Upon return, Councilmember Lee had no further questions on the Wilburton neighborhood.

In her comments, Mayor Robinson emphasized improving Bellevue’s tree canopy at the potential expense of housing flexibility.

“A lot of times, land use dictates our tree codes, and I would really like to see tree codes dictating land use,” Robinson said. “I sure would rather start with the goal of a tree code, and then start planning how much infill we can do rather than, we’re going to put all this housing in and then we’re only going to have room for 10 trees.” In a follow up question to staff, she further implied that she would like the city to prioritize the importance of trees in its code over buildings.

Bellevue has a citywide tree canopy coverage goal of 40% by 2050. As of the last assessment conducted in 2019, the city is one point shy of the mark at 39%, but that coverage is not equally distributed across all city neighborhoods. Councilmember Robertson followed up on the mayor’s comments by suggesting the city evaluate a systematic approach to tree canopy that looked at assigning desired canopy square footage given a particular land use type.

The city’s Planning Commission is currently considering amendments to Bellevue’s tree codes with the aim to incentivize tree retention and penalize unpermitted tree removals during redevelopment. Similar to the Comprehensive Plan process itself, the Planning Commission’s tree code proposal will ultimately be reviewed by Council before final adoption. These comments signal the potential for significant changes that could negatively impact housing production.

Still More Decisions to Come

Staff have not yet publicly released a final land use map that reflects Council’s changes to the Planning Commission’s recommendation, so it’s still unclear just how much housing capacity is allowed for under the body’s approved Preferred Alternative. What is clear is that, after the Final EIS is completed in the fall, Bellevue City Council will be required to craft a land use map that reflects some combination of the four alternatives thus far evaluated. This leaves a wide range of possibilities, with housing diversity and significant capacity allowed throughout the city on one end of the spectrum and minimal growth that largely maintains the status quo on the other.

On an optimistic note, the city could fall back onto the already-studied Alternative 3 when crafting its land use codes, which would allow for 95,000 additional housing units spread more equitably throughout the city and its diverse neighborhoods. However, given the ideological split of the Bellevue City Council, significant movement toward this alternative would likely require a major political shift that makes the watered down alternatives untenable — an outcome that existing institutions will likely aim to make incredibly difficult.

Chris Randels is the founder and director of Complete Streets Bellevue, an advocacy organization looking to make it easier for people to get around Bellevue without a car. Chris lived in the Lake Hills neighborhood for nearly a decade and cares about reducing emissions and improving safety in the Eastside's largest city.