The agency needs more trains, fewer pinch points, and a commitment to operational efficiency.

Sound Transit has been slow-walking details about the agency’s inability to provide long-promised service levels on Link. As light rail expands without sufficient fleet capacity, service is poised to regress to no better than 10-minute frequencies and many more trains could run with three cars instead of the usual four. A compounding set of errors by agency planning processes and unforeseen circumstances have led to the problem, which could persist not only for a few years but decades.

The agency’s best effort has been a suggestion that 10 additional Series 2 Link cars be procured to offer more four-car trains later this decade. But that suggestion doesn’t negate the long-term service frequency and capacity problems that riders will be condemned to face without more substantial actions. The likelihood of crowding issues and missing frequency promises should be raising alarms and spurring Sound Transit boardmembers to action.

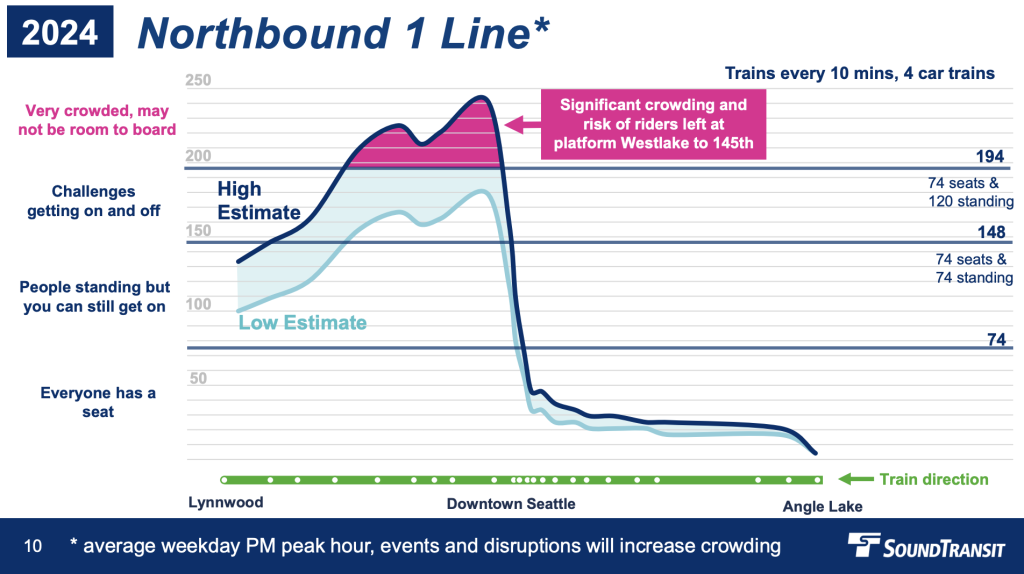

Fundamentally, Sound Transit is failing riders by not delivering on promised headways and consistent four-car trains.

Link service shouldn’t be going off the rails

Link has always been billed as the region’s central spine for transit mobility, making it the critical connection point for other transit service and a workhorse for rapid movement across key corridors. Fewer trips and train cars doesn’t just squeeze riders with longer waits and unboardable trains, it also suppresses transit ridership throughout the network relying upon it.

For some, it may be politically expedient to blaze ahead with Link expansions for the sake of earlier ribbon-cuttings, but the latest round of revelations show that solving for capacity and frequency issues should be the top priority. The fix may involve slowing expansions, if need be, so that Sound Transit can take a comprehensive approach to fully deliver on the promise of the Sound Move and Sound Transit 2 capital expansion programs. That promise is to reliably provide eight-minute frequencies, four-car trains, and extra service when needed, and those programs are not complete until that promise is met.

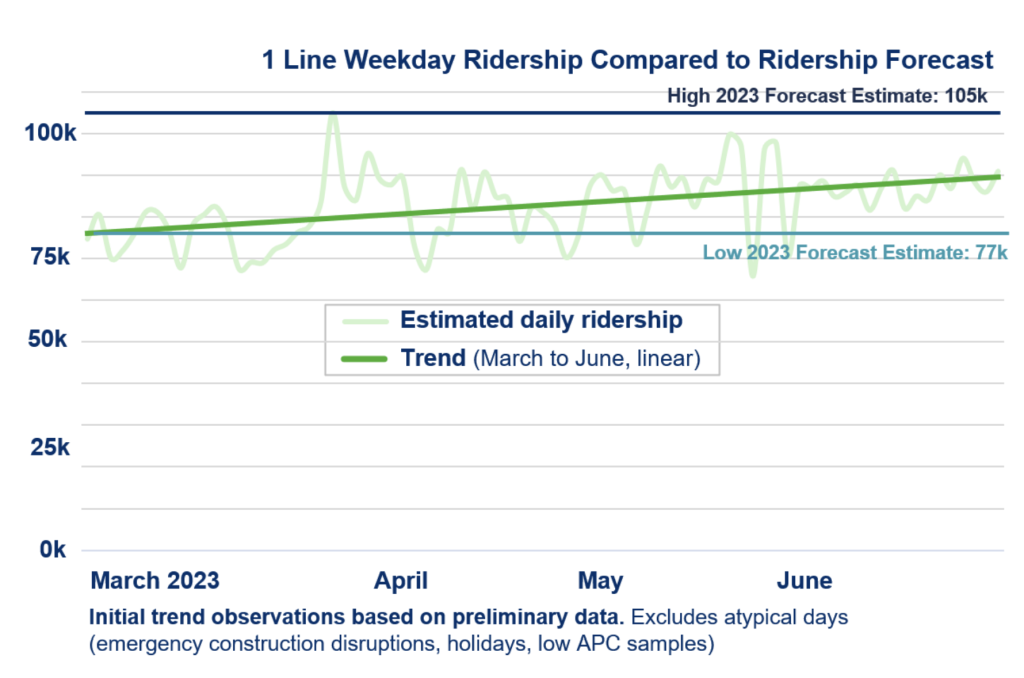

It’s important to recognize that ridership patterns were different before the pandemic. A lot more trips are now happening in the midday period and on weekends. Growing ridership is putting pressure on the system and if that continues it will be a recipe for disaster without corresponding service increases.

Segments of the system should be getting the level of service that truly reflects the demand. That’s why just four years ago the system was brimming with ridership prior to the pandemic when Link only operated between Angle Lake and University of Washington stations. It’s easy to forget that service was running at six-minute frequencies during peak hours then to support robust ridership.

Sound Transit’s own service planners are saying that Link ridership growth is trending closer to their higher ridership forecasts. That portends a likely scenario that ridership growth will continue to rise at faster rates than the average and lower forecast models, and the consequence of that could be leaving riders stranded at platforms and additional cascading operational problems.

So far, Sound Transit has been acting like it’s an innocent bystander with problems being heaped on it with little agency to solve them. But Sound Transit does have other strategies that it could put into action to restore service and blunt future problems.

Strategies that could improve the situation now and in the future

One of the biggest drags on Link vehicle utilization and availability is its at-grade segments and rail infrastructure. That’s led to trains running six to eight minutes slower, requiring more trainsets to provide the same level of system frequency and capacity. Some relatively low-cost strategies could be employed to rectify that:

- Corrective actions in the Rainier Valley segment of Link and other at-grade sections could be taken, such as closing more intersections to cars, trimming down the width of rail crossings, and installing protective crossing gates. This would help improve reliability in the corridor, allow faster speeds, cut travel times, and keep more Link cars in-service, in addition to knock-on safety benefits for other users of the corridor.

- Installing more crossover tracks throughout the network would help trains navigate around stalled trains or other temporary service disruptions. That would allow for better system reliability and operations when there is a pinch in the system.

- Repairing and replacing any other deficient infrastructure that is unnecessarily slowing trains would give a big bang for the buck. Sound Transit has already been doing a lot of this as part of the Future Ready program but there may be additional opportunities abound.

The interior design of Link trains is inefficient, leading to long dwell times as riders fight to get on and off trains during heavier ridership periods. That means longer trip times. Some things Sound Transit could do to improve the situation include:

- New tools and audio announcements on- and off-board could be developed and deployed to help with efficient boarding and deboarding practices, directing riders to less crowded cars, and avoiding confusion.

- Train interiors could be retrofitted to switch at least half of the main forward-facing seating to longitudinal seating to allow for easier circulation and more standing room. Giving more clearance near doors could also allow for more space to shuttle on and off trains.

The lack of trains is certainly a challenge, regardless if the aforementioned strategies are implemented. The agency has already reported that 90 or so additional light rail cars than planned would be needed to provide six-minute frequencies promised in Sound Transit 3 Link expansions. But that problem exists imminently, too, so tackling this issue now seems prudent. Strategies that could be pursued include the following:

- Sound Transit could commit to shuttling extra trains to run on the 1 Line as soon as the I-90 corridor is operational for non-revenue service.

- Going well beyond the 10 additional Link Series 2 cars that the agency may wind up procuring, Sound Transit could purchase several dozen more cars — flawed as they may be. Under the current contract with Siemens, Sound Transit has remaining options for 16 cars but could be well positioned to exercise the extra six and push for more. According to the agency, staff are only settling on the 10 extra cars because of remaining storage capacity at its two operations and maintenance facilities (OMFs).

- Getting more creative with storage of Link vehicles overnight would further increase the agency’s ability to take on a larger fleet earlier. Earlier this year, agency staff suggested alternative storage locations at select stations but have since retreated from this without a clear explanation, but that idea could go much further until more storage space at OMFs can come online. For instance, the agency could leave trains parked at tunnel stations, some elevated stations, and on pocket tracks, allowing for storage of dozens of cars. Indeed, wrapping up and starting up service as well as transporting staff to and from those locations may be an operational challenge, but it could be a very worthwhile one for an intermediary period of time.

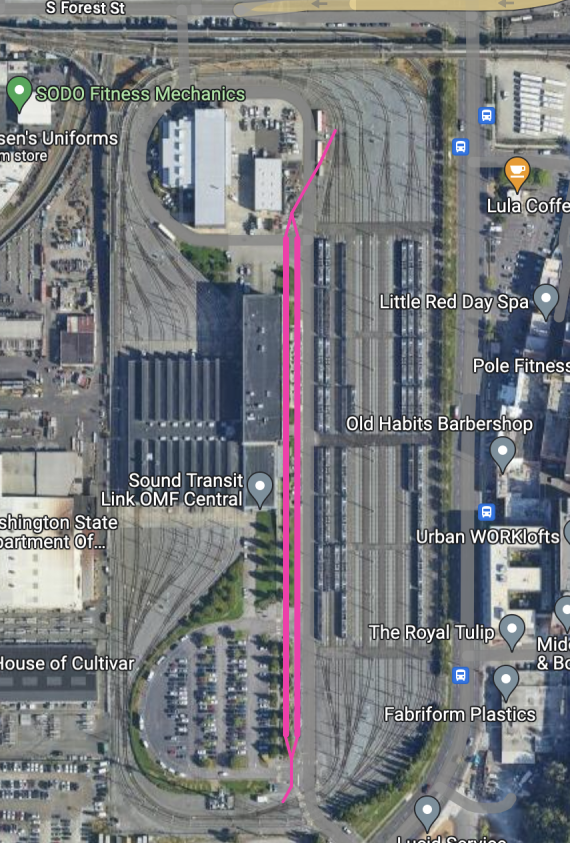

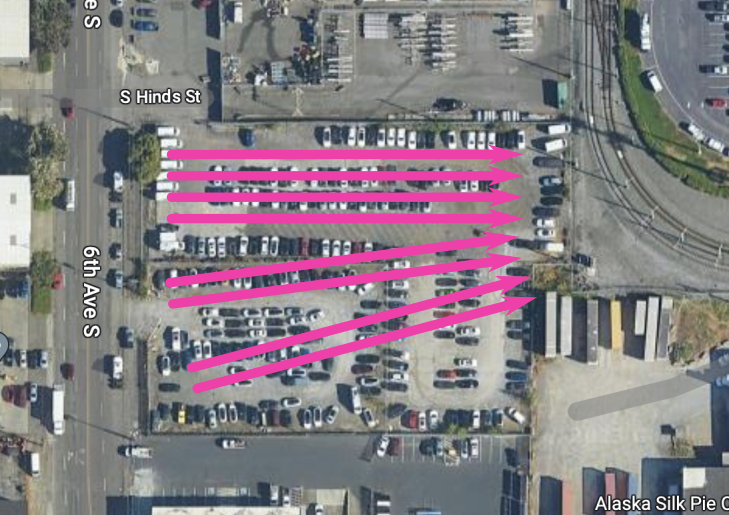

- OMF Central in Seattle appears to have remaining space within it that could be reconfigured for storage of 20 or so Link cars. That could involve construction of two new parallel tracks and access space to the tracks for staff by eliminating some car parking and landscaping. That type of action has the potential to be exempt from both federal and state environmental review processes, so it could happen relatively quickly as a construction solution.

- Sound Transit could further expand OMF Central to take in adjacent properties. For instance, acquiring two lots to the southwest of the facility could support up to eight tail tracks for storage of many more Link cars. The process for this would obviously be more involved than on-site improvements and could trigger heftier environmental review processes, but a strategic expansion could solve most of the intermediate system service level and capacity problems.

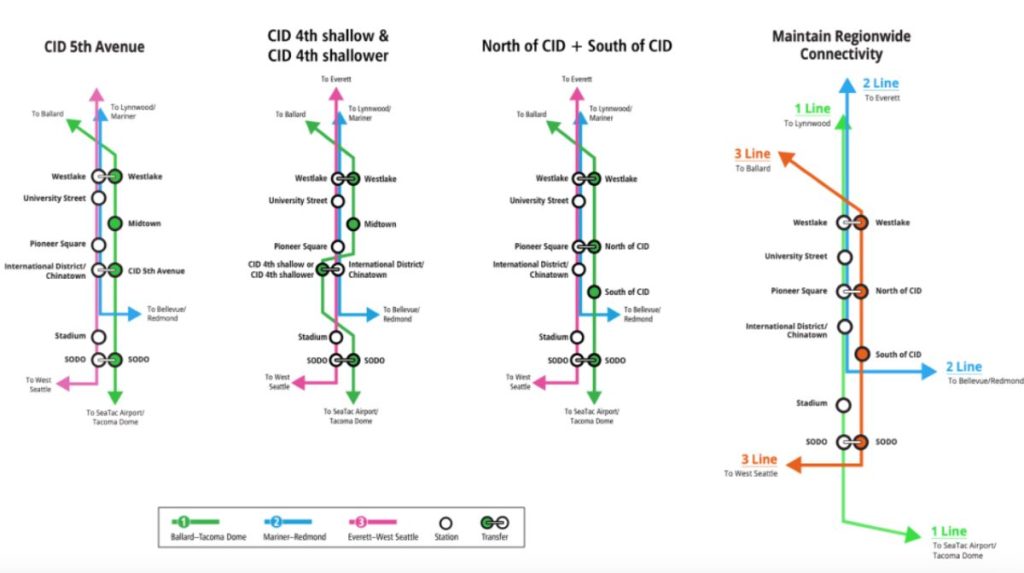

On top of this all, Sound Transit planners would be well within their rights to fully rethink the Sound Transit 3 system operating plan. This could involve coupling the West Seattle and Ballard Link Extensions (WSBLE) into a single unified line. And while that would mandate a new OMF in Seattle and some design rework, it would allow the agency to mitigate a lot of problems it faces in the future and serve riders and communities better.

A closed line could reduce the size of planned OMFs in Federal Way and Snohomish County and greatly reduce the number of Series 3 Link trains needed. That’s because a unified WSBLE line could be fully automated and run with just two-car trains at much higher frequencies than other Link lines. Another upshot is that the footprint of WSBLE stations could be considerably smaller, less impactful and easier to construct, and less costly to build. Even semi-automation of other lines could be a useful goal to improve system operations.

These ideas are by no means exhaustive of potential solutions, but they’re a lot more ambitious and impactful than the ideas agency staff have been publicly sharing. Management and the board need to press staff to bring more ideas into the fray now, rather than letting them be squashed by internal agency processes. Agency staff offering only one bona fide solution to Sound Transit 2 Link expansion woes couldn’t be a more clear signal that things aren’t working well on the inside right now.

Long-standing promises shouldn’t be brazenly broken

Ultimately, Sound Transit and its board need to understand that Link isn’t a bus, and the agency shouldn’t be in the business of treating it as such. Voters and partner agencies have approved billions of dollars to construct Link exactly because it’s a train, not a bus. But 10-minute frequencies and short trains tell the tale that Link is being run like a glorified bus. A rail line needs high frequencies and sufficient capacity to serve as the backbone of the regional transit network.

If Sound Transit won’t improve service to six-minute frequencies and restore train capacity long before Sound Transit 3 Link extensions open, it could have a public relations nightmare on its hands as the agency continues to fall short of promised service levels and overcrowding squeezes out riders in the busiest segments. Without rebuilding trust and getting the details right, the agency has no business pursuing any of those expansions.

Sound Transit is running headlong into an operations mess and at risk of breaking the promises that sold the region on light rail in the first place. The agency’s board should start forcing the agency to deliver on those promises instead. Time is of the essence.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.