The move could be a jolt to a long-delayed plan for the decommissioned site, spreading infrastructure costs across more homes — if the bid succeeds.

The saga of building affordable housing at Fort Lawton had been shaping up to be a never-ending tale, but today Mayor Bruce Harrell revealed a twist that might finally deliver a conclusion — at least after more suspense and Seattle Process. The mayor announced his intention to upgrade the 237-home proposal to one that could deliver as many as 500 homes on the 34-acre site, while preserving the majority of the site as green space as the original plan promised.

“Building on an earlier redevelopment plan that was approved by City Council in 2019 and then delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic, an improved plan would build as many as 500 units of affordable housing, optimizing the number of affordable homes to address Seattle’s housing crisis, while significantly lowering per-unit costs,” the mayor’s office said in a news release. “These additional units offset some of the considerable infrastructure costs required for the project while maintaining 22 acres for open space, parkland, and wildlife conservation adjacent to Seattle’s majestic Discovery Park.”

The number of units envisioned on the site had remained relatively unchanged since the City first released a redevelopment plan for Fort Lawton in 2008, under Mayor Greg Nickels.

The mayor’s news release pointed to need to upgrade roads, power, water, and sewers on the site, located in a sparsely populated corner of the Magnolia peninsula that is wedged between the city’s largest park, a bluff, and, a ravine. “The additional analysis conducted by the City since 2022 revealed opportunities to reduce per-unit infrastructure costs not only by increasing the number of units but by altering the approach to street and other infrastructure improvements,” the mayor’s office wrote.

Overcoming more than a decade of local homeowner opposition and legal obstruction, that 2019 council vote had seemed to have cleared the way for 237 affordable homes on a site decommissioned by the U.S. Army and offered to the City of Seattle at low- or no-cost — if they repurposed the property for public use in a timely fashion. However, the slow advance of the proposal and climbing infrastructure costs caused the Harrell administration to rethink the earlier plan.

“The scale of our affordability and homelessness crises requires us to make the wisest possible use of our limited housing dollars in order to achieve the largest possible impact,” said Mayor Bruce Harrell. “In a city of 84 square miles, the Fort Lawton Redevelopment Plan is a unique opportunity to transform 34 [acres] into a new community that will last for generations — we must make the most of it. This is our One Seattle vision in action — a city with affordable homes and communities where every Seattle neighbor can access the good jobs, schools, and supports needed to grow and succeed.”

The Office of Housing is working on the plan to increase the types of housing at Fort Lawton, but that plan isn’t promised to be delivered to city council until “sometime in 2024 or 2025,” according to the project website. Councilmember Tammy Morales, who has championed social housing, told The Urbanist she was supportive of adding more housing, but sick of delays.

“I’m a little frustrated that there was such a long delay and that this would actually cause more delay,” Morales said. “But, we could finally get this going and have the opportunity to finally build housing there. I think that’s gonna be important.”

Delays have meant the City has missed a window with low interest rates and relatively cheap construction costs that could have delivered the project more efficiently. While officially Mayor Jenny Durkan backed the project in 2019, her administration was slow in actually delivering it.

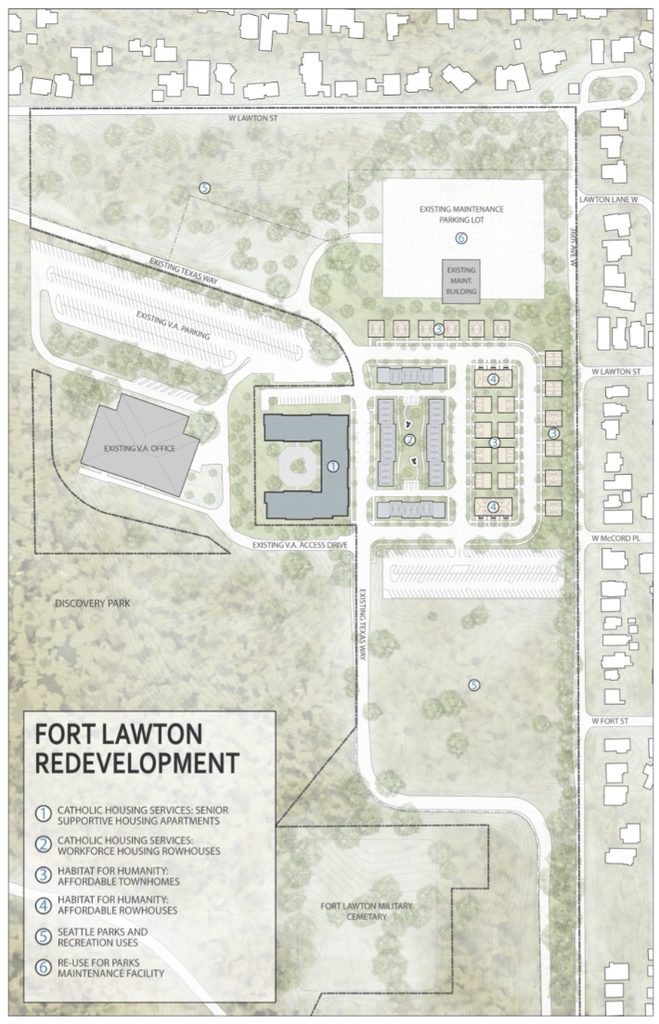

The original 2019 plan’s 237 affordable homes included 100 rental homes for low-income people and families, 85 homes of permanent supportive housing, and 52 homes for ownership. It was originally estimated to come in at about $90 million, but construction costs have ballooned since then — and that’s even before accounting for street and utility upgrade costs, which have also risen as the construction sector has been hard hit by inflation. “Infrastructure estimates range from a low of $31 million to a more conservative $105 million,” the Office of Housing said.

Street and utility costs potentially rising above the original housing cost estimate caused the Harrell administration to go back to the drawing board. A bigger project could better justify the infrastructure costs. Issuing a $200,000 contract, the City hired real estate consulting company Heartland to study alternatives, and the consultants issued a report in October.

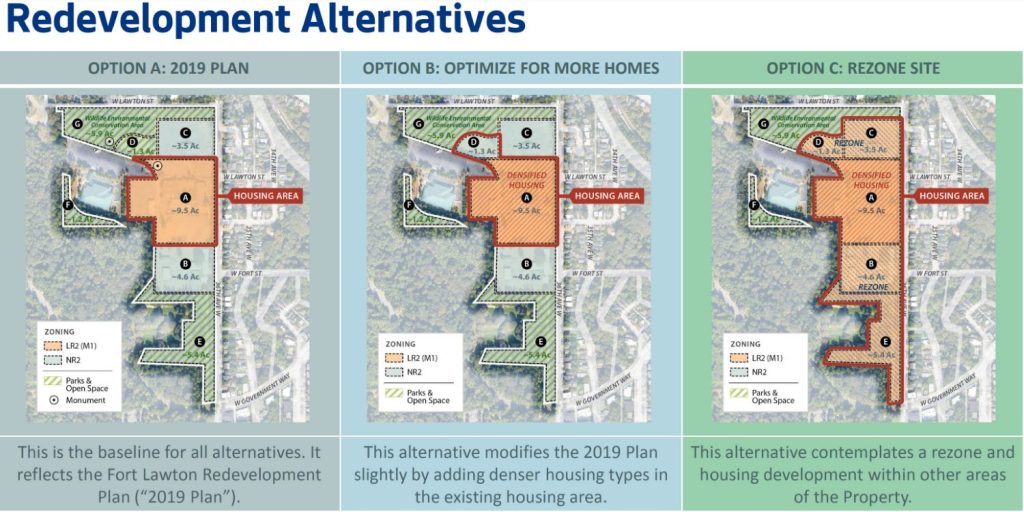

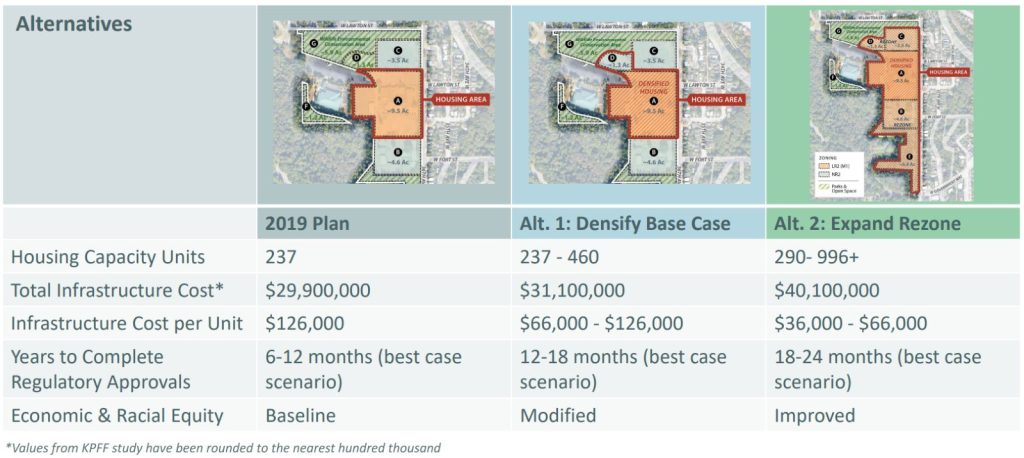

- Option A: 237 homes under existing plan, with per-unit utility cost estimated at $126,000.

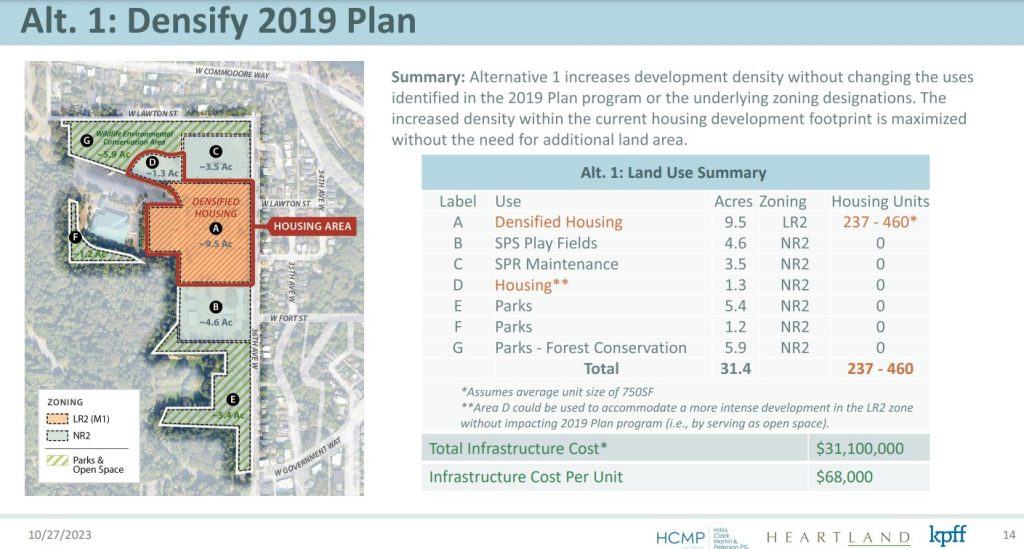

- Option B: Up to 500 homes, with per-unit utility cost estimated at $68,000. Adds 1.3 acres to housing area.

- Option C: 996 homes, but predicated on rezone and adding 15 acres to housing area. Lowers per unit utility cost to $42,000.

With roughly 500 homes, Option B costs more but achieves a better cost per unit. “For the optimized plan (Option B), we now estimate the project will cost about $285 million,” according to the Office of Housing. “The total cost for Option B is higher than Option A, but Option B adds enough homes to bring the estimated development cost per unit down to $496,000, close to the average City-funded affordable housing project.”

Option C, meanwhile, would study zoning changes to get even more out of the site. Some green space would remain, but a significant portion could be traded for more room for housing. The study assumed Lowrise 2 zoning throughout the housing area, meaning going beyond LR2’s 40-foot height limit (and 1.4 floor area ratio limit) was not studied. The consultants explained the zoning assumption as seeming consistent to the neighborhood in their estimation: “The LR2 zone was used for this analysis because it represents the next step in density and is the most consistent with surrounding uses and the 2019 rezone.”

The mayor’s office did not yet sketch out Option C beyond these broad parameters — expanding the housing area on the site by approximately 15 acres, for a total of 24 acres of the 34-acre site. But the option remains technically on the table, even as the mayor throws his weight behind Option B.

While offering the smallest overall price tag, the existing plan would incur a per-unit infrastructure cost of $126,000, the Heartland report said. “The somewhat denser plan would have a lower per-unit infrastructure cost, of $68,000,” Daniel Beekman reported in The Seattle Times on Sunday. “The much denser plan would have an even lower per-unit infrastructure cost, of $42,000, though it would require zoning changes at the site, the report said.”

The mayor’s press release notes that City Council approval would be required for the new plan, as well as from the federal government for the land transfer to the City. “A new Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement [EIS] process will be conducted, with opportunity for public comment, followed by the Office of Housing submitting the amended redevelopment plan to City Council and to HUD,” the mayor’s office said. “The City expects to begin infrastructure design and construction in the second half of 2025, after completion of the processes outlined above and a request for proposals for infrastructure work in the second quarter of 2025.”

The infrastructure work would need to be completed before housing construction could begin in earnest, Office of Housing spokesperson Nona Raybern said.

Housing advocates may push the City to look at Option 3, which could deliver nearly 1,000 homes on the site. However, picking that option may entail more delays to work out the details of the rezone and the larger development plan. That said, if the rezone happened as part of the Seattle Comprehensive Plan update due by the end of 2024, the delay may be fairly insignificant. Whatever the alternative, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) will need to sign off.

Harrell made his case in a December 27 letter to HUD seeking an extension on the due date for the land transfer. While he noted the headwinds the city’s looming budget crisis creates to funding housing, he pointed to steps the city was taking to encourage development and alluded to the passage of Seattle’s $970 million housing levy in November.

“Despite the real budget crisis we are working through, my administration has worked steadfastly to tackle the affordable housing crisis in Seattle. Our approach includes expediting housing production, streamlining permitting and record-low utility connection times, and historic investments to house the homeless and build affordable and accessible housing.

Pursuing either Option A or B, it appears the best case scenario is that people could start living in new housing on the Fort Lawton site by 2027 at best, but longtime observers of this saga surely expect more twists, delays, and setbacks around any corner. The supplemental EIS provides opportunity for a fresh round of appeals from housing opponents. A series of appeals from Magnolia homeowner and frequent activist Elizabeth Campbell has already been a serious impediment.

Washington State’s federal delegation has pledged their support to help steer the proposal through the (often onerous) federal approval process. Failure to come up with a viable proposal could mean forfeiting the City’s claim on the site, since the decommissioning and ownership transferring process has a time limit, and the City of Seattle has already needed to seek extensions.

“Ensuring that everyone in Washington state can keep a roof over their head has been, and continues to be, one of my top priorities,” U.S. Senator Patty Murray said in a statement. “We have a real housing crisis on our hands, and I am laser focused on boosting our affordable housing supply across the state. The Fort Lawton project is a promising one and could make the world of a difference to hundreds of Seattle families. I look forward to reviewing the city’s plan and continuing to work with HUD as they review this application.”

In prepared statements, Councilmembers Dan Strauss and Cathy Moore backed the mayor’s plan. Fort Lawton is located within Strauss’s Council District 6.

“This plan to redevelop Fort Lawton will help ensure that families like the one I grew up in can afford to live in the Seattle of today and the Seattle of tomorrow,” Strauss said. “Every iteration of this project has increased the amount of open space, wildlife habitat, and housing opportunities for everyday Seattleites. This is a generational investment that will pay dividends for decades to come.”

“As the incoming Chair of the Housing and Human Services Committee, I applaud Mayor Harrell’s proactive approach to increasing desperately needed affordable housing as well as permanent supportive housing in our city,” Moore said. Moore was sworn in last Tuesday for her first term, and her committee has not yet held its first meeting.

Nonprofit housing providers remain committed to the plan as well. Catholic Housing Services and Habitat for Humanity Seattle-King and Kittitas Counties remain the developers of the proposed housing, and United Indians of All Tribes will be the service provider for the permanent supportive housing at Fort Lawton, the mayor’s office said.

Patience Malaba, who is executive director of the Housing Development Consortium, saw the new plan as an improvement.

“We are thrilled to see progress on the Fort Lawton redevelopment, after nearly two decades of planning,” Malaba said in her statement. “The Mayor’s plan to add more affordable homes on the site helps make the project more cost-effective, as well as better addressing our community’s critical need for affordable housing. This development fulfills long-standing promises by adding hundreds of new affordable homes next to Discovery Park. The housing will support those across the income spectrum, from low-income homebuyers to individuals exiting homelessness.”

More than that, Malaba said the project could be a potential statement for the neighborhood and the city at-large.

“But the Fort Lawton redevelopment is about more than just buildings — it’s an opportunity to ensure all neighborhoods of Seattle are truly inclusive communities where people of all backgrounds can thrive,” Malaba continued. “Together we can journey towards a future where no family is left without a safe, affordable place to call home.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.