With ongoing crises around traffic safety and inequitable access to basic mobility, Seattle streets do not work well for everybody. Seattle’s 2024 transportation levy renewal is a big chance to transform them for the better, but will Mayor Bruce Harrell take it? The mayor is expected to outline his proposal this week and appears likely to disappoint advocates who asked for a levy that makes road safety the top priority and strives to transform streets for the better. Those advocates proposed $3 billion in investments in safe walking, rolling, biking, and reliable transit.

The new eight-year levy would be a successor to Move Seattle, a nine-year transportation levy approved in 2015 and set to expire at year’s end. That levy was a $930 million package that funds about 30% of the City’s transportation budget. Not passing a successor would blow a huge hole in that budget right as the City is grappling with a large general fund deficit, which is estimated around a quarter billion dollars in 2025. It would also severely limit Seattle’s ability to provide a local match to go after federal dollars at time when they are flowing in the wake of Congress passing President Biden’s jobs and infrastructure bill.

However, with the City falling behind on key climate goals and actually going backward recently on its Vision Zero pledge to end traffic deaths by 2030, the coalition of mobility advocates argues now is the time to accelerate investment rather than coast. The coalition includes Disability Rights Washington, Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, Cascade Bicycle Club, Seattle Subway, Transit Riders Union, 350 Seattle, House Our Neighbors, Real Change, Puget Sound Sage, and The Urbanist. [The Urbanist’s advocacy staff and volunteers participate in coalitions independently of our news team.]

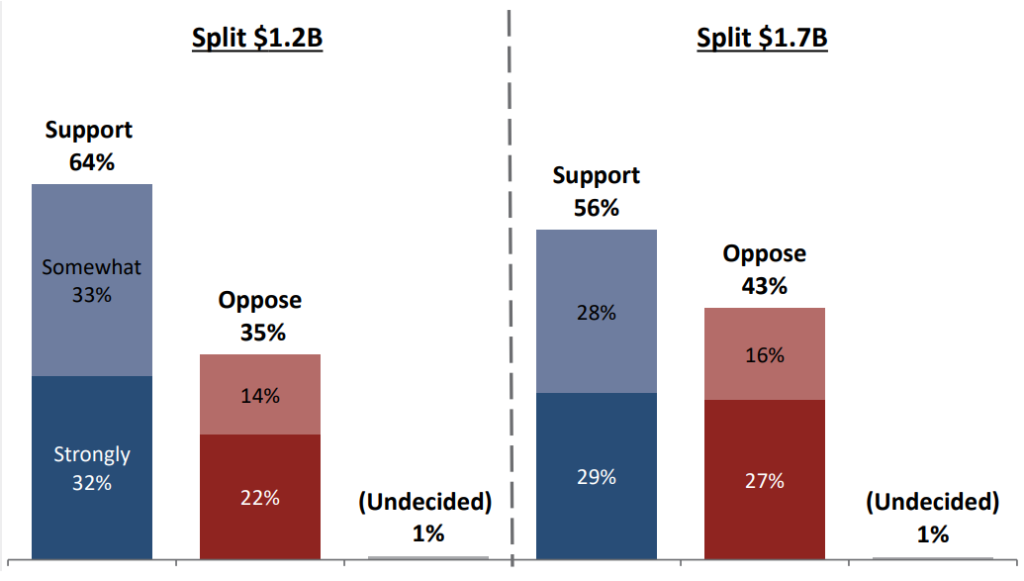

In January, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) released a poll it commissioned that revealed the scope of investments the City is considering. SDOT polled on two levy options: one that only manages to keep up with inflation at $1.2 billion and another at $1.7 billion. Both polled well above water and appeared very likely to pass, but the smaller package did enjoy a larger margin, which led some to predict the Harrell administration would pursue this as the path of least resistance.

Based on reports from city hall, Mayor Harrell is likely to announce a levy package somewhere in the middle of the two goalpost figures, just as he did for the Seattle Housing Levy, where larger versions had been considered but rejected. The $970 million version of the housing levy the mayor landed on ended up passing with 69% of the vote in 2023. Clearly, a larger package that produced more affordable housing would have been feasible, in retrospect.

It could be the City is planning to leave revenue for transformational investments on the table again, with a levy in the ballpark of $1.4 billion instead of the $1.7 billion package that SDOT’s own polling found would pass rather easily and deliver high-impact projects. Such a proposal would not approach anything close to the $3 billion ask from advocates.

Most are expecting the mayor’s proposal to emphasize road maintenance rather than promising marquee projects to improve to transit, biking, or safety. In contrast, advocates are urging that a majority (at least 50%) of the levy to be dedicated to pedestrian, bike, and transit projects, rather than car projects, but it looks like this draft will fall short of that. Thus, going small and car-centric could lead to an enthusiasm gap from the transportation advocates who are usually expected to be standard-bearers for the levy during the campaign. There have even been rumblings that some groups would sit the levy campaign out or even endorse a no vote.

Pushback from advocates has led to discussion of what would be a threshold of an acceptable package that doesn’t just maintain the status quo approach but makes major headway toward the city’s safety, climate, and mobility justice goals. While they asked for $3 billion focused on pedestrians, safe cycling, and transit, advocates understand the City was extremely unlikely to go that far, but failing even to meet them halfway would make it tough to get excited.

Here’s some ideas of what a levy package should include to address safety, keep us on track to the City’s long-term goals, and get advocates excited.

Redesign Seattle’s five deadliest streets to be safe

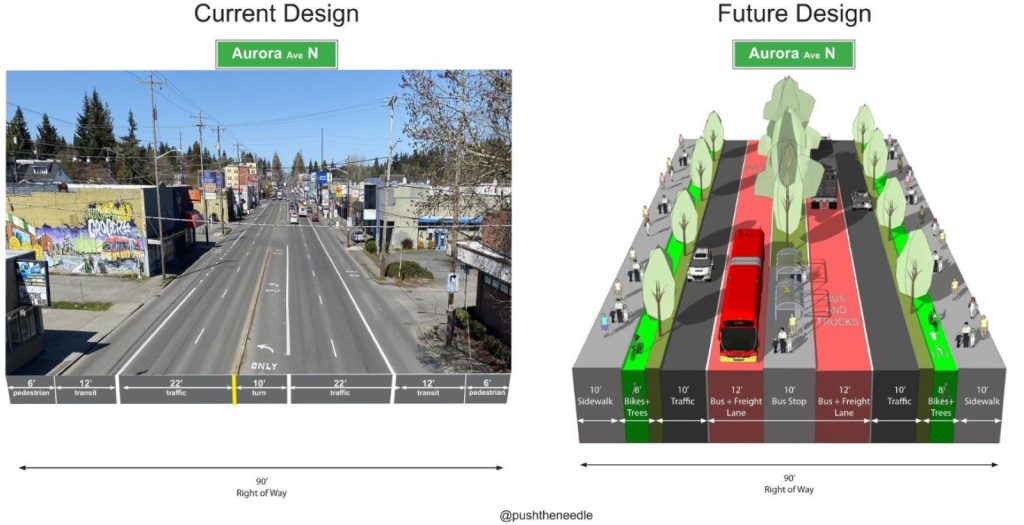

The advocates’ proposal to redesign five of Seattle most deadly streets to be safer is a no-brainer idea if the City is serious about Vision Zero and safer streets. The Urbanist’s Ryan Packer went so far last week to say redesigning Aurora Avenue, the city’s most deadly street, is the City’s “pass/fail test” on Vision Zero.

Advocates are not seeking window-dressing changes, such as adding a flashing beacon here or there. We’re talking about a significant re-prioritization of space throughout the corridors to ensure people are safe when using the street and that transit is a viable and reliable option rather than an afterthought. The five corridors flagged by advocates are as follows:

- Aurora Avenue N – 22 people killed in the last 5 years

- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Way S – 13 people killed in the last 5 years

- 4th Avenue S – 11 people killed in the last 5 years

- Rainier Avenue S – 10 people killed in the last 5 years

- Lake City Way – 5 people killed in the last 5 years

Tackling high-crash corridors with safety-focused redesigns are the highest impact action that the City could take to curb traffic deaths and collision injuries.

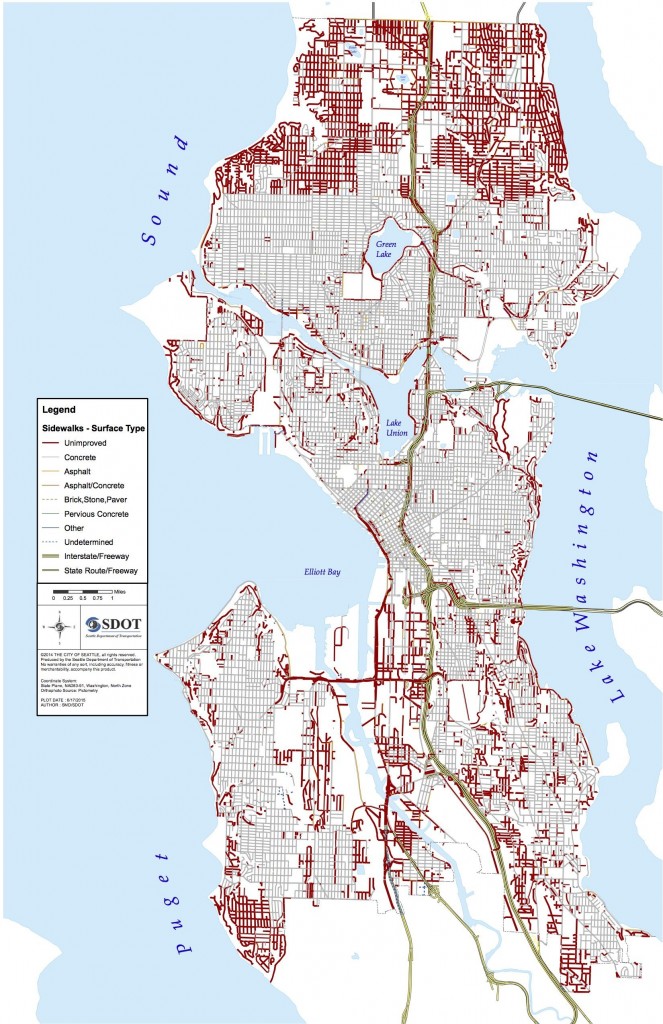

Major strides to close the sidewalk gap

Sidewalks are a popular topic these days, with a lot of city councilmembers stressing their importance on the campaign trail and now dais, which is refreshing to see in Seattle politics. Given this broad support, Mayor Harrell shouldn’t be shy about proposing big investments in sidewalks. Adding sidewalks where they are lacking or woefully insufficient is not cheap, since usually drainage work must accompany them and the laborious Seattle Process also adds cost. However, if it’s a priority, we should get it done.

The advocates’ vision was to add 331 miles of new sidewalks, composing nearly $700 million of their $3 billion package. Seattle will never close its missing sidewalk issue if it doesn’t start thinking on a scale of this magnitude. At its current pace of construction, Seattle would take more than 800 years to close its sidewalk gap. Going at the pace of the last levy is far from enough.

It’s crucial that the intersections get careful attention, too, since the lion’s share of injury collisions happen there. The advocates propose 750 intersections with upgraded safety treatments and 320 accessible pedestrian signals.

Advance the bike network and street pedestrianization

Advocates asked for 154 miles of new safe bike lanes in their levy proposal. It sounds like they’re likely to get far less than that. While 154 miles might not be in the cards, the levy must make a major step forward in filling out the bike network, which are most severe in the South End. To attract more people to biking, the network must be safe and comfortable to cyclists of all ages and abilities.

Neighborhood greenways can be a great supplement to the bike network, but they cannot replace the need for protected bike facilities on major streets where businesses and amenities (and thus destinations for cyclists) are located. Plus, greenways need enough traffic calming and diverters to actually feel safe for users of all ages and abilities. Otherwise it’s not truly a pedestrian-focused street, but just a typical residential street with some extra signage and a prayer.

Speaking of, taking the leap and doing some full street pedestrianization projects is another request from advocates that would reframe our streets as place to be rather than just shuffle though. This would be a big quality of life gain.

It will be very hard to meet climate and safety goals without making biking a safe and pleasant choice for all — as opposed to a harrowing, white-knuckle dance to avoid becoming a hood ornament, daredevils only apply. Seattle is in the middle of an e-bike boom, and the City needs to be planning for success and the popularity of biking and scooting rather than planning for failure with insufficient facilities.

The mayor and council appear intent on focusing on repaving work, but we need not repave streets exactly as they were. Repaving projects are golden opportunities to add protected bike lanes, wider sidewalks, and/or bus lanes. But it takes a commitment from the City to pursue such an approach to trust repaving work isn’t just cementing the status quo.

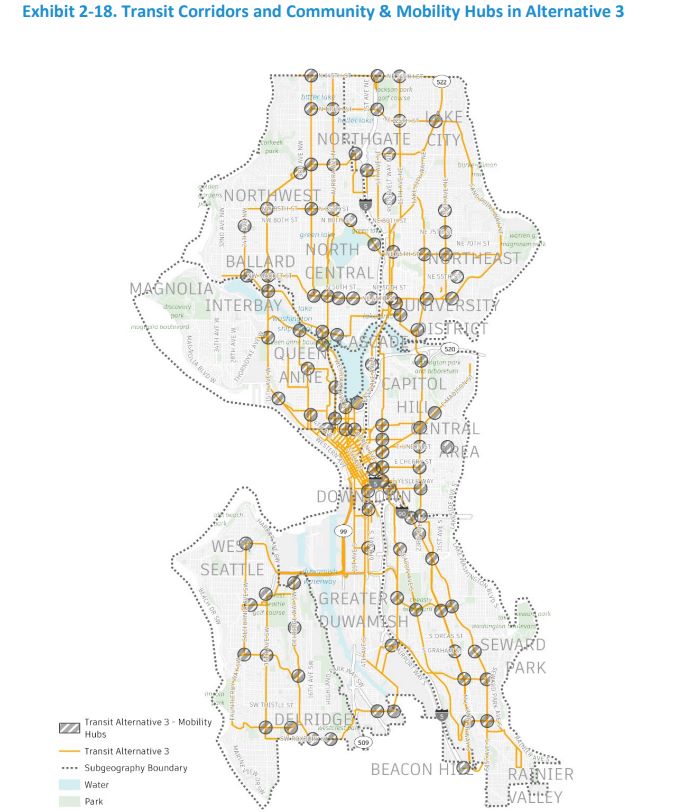

Investments that make transit faster and more reliable

Transit is in a place of complacency and delay right now and the levy could reinject some purpose and ambition. In their proposal, advocates called for 60 miles of new dedicated bus lanes across nearly a dozen routes to speed the city’s most sluggish workhorse buses. As with bikes, every district of Seattle should be able to see the levy package and point to a bus improvement that would make their transit commute much more reliable and smooth.

New state-provided authority to enforce transit lanes with automatic traffic cameras can make bus lanes much more effective, ensuring buses can stay on schedule rather than get blocked by car traffic and scofflaws.

Beyond Aurora Avenue’s RapidRide E Line, bus corridors that advocates highlighted as in need of speed and reliability improvements include Route 5, 21, 36, 40, 48 and a greater emphasis on reliable crosstown with upgrades to Route 8, 44, 50, and the revised Route 65, which will connect Bitter Lake and Lake City. These are heavily-used buses even with their issues with unreliability and sagging frequencies. Imagine how effective and popular they would be if we gave them the attention and care that they deserve.

Improve and widen multi-use trails

The advocates’ vision did not forget about the off-street trail network, which is a backbone for commute and recreational use alike. They proposed $100 million to improve and widen trails such as the Burke-Gilman, Chief Sealth, and Alki/West Seattle Comfortable Connections. Such improvements are likely to be popular with voters, since nobody loves walking, rolling, or biking in overly congested trail bottlenecks. Plus, wider trails with safer crossing would be better prepared to handle an influx of users as the city grows and shifts away from car dependence.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.