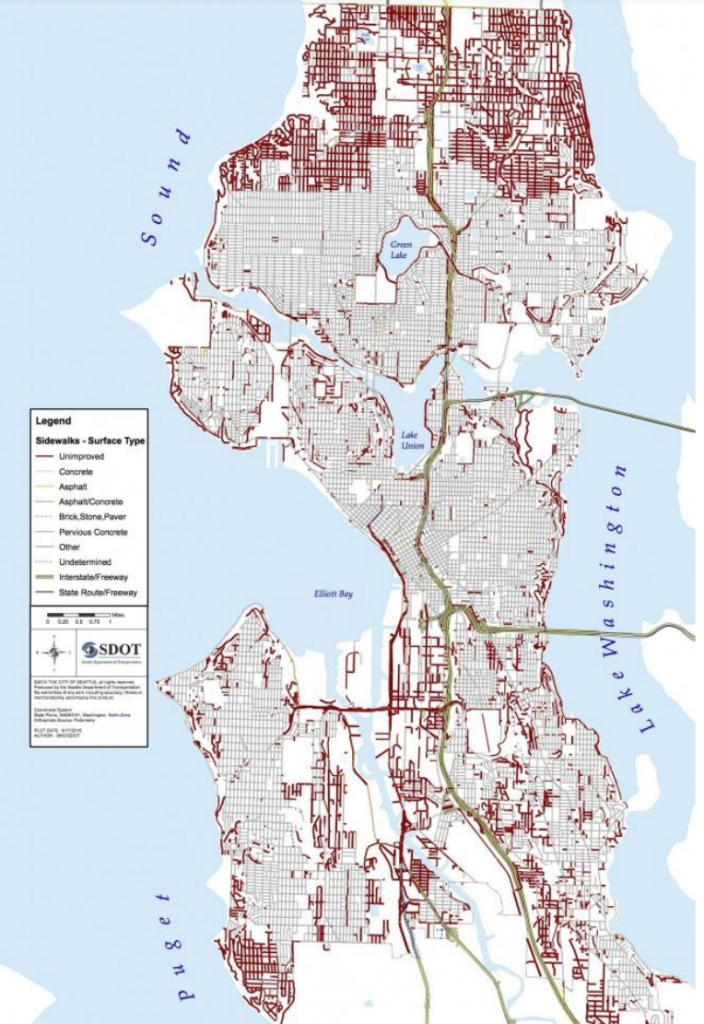

The draft eight-year, $1.35 billion transportation levy proposed by Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell early this month doesn’t propose to dramatically change the pace of new sidewalk construction in Seattle, instead promising a continuation of the current goal of around 30 city blocks per year, or 250 by the end of the 2032. That announcement has disappointed mobility advocates who have been pushing the city to ramp up its efforts to complete the missing sidewalk network, with 27% of Seattle’s blocks today lacking the basic pedestrian infrastructure that a sidewalk represents.

At the current pace, Seattle won’t be able to say every block in the city has a sidewalk for another 400 years.

Numbers crunched by Ethan Campbell, an organizer with Whose Streets? Our Streets!, conclude that the new levy is actually a decrease in annual funding for pedestrian projects, including, with an inflation adjusted decrease of 23% per year. But Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) officials argue that the dedicated pedestrian funding streams won’t be the only funds available in the new levy for sidewalks, and cite around $10 million for new sidewalks along Aurora Avenue N as part of the $30 million earmarked for corridor improvements on that state highway.

Seattle’s transportation levy currently only accounts for around half of the annual funding for new sidewalks, with dollars from the city’s school speed zone cameras, real estate excise taxes, and federal and state grants making up the other half. But advocates see a contrast between the significant focus that the proposed levy gives to roadway maintenance via $423 million for repaving projects, including, for the first time ever, dedicating levy funds to everyday pothole repairs, which had traditionally been funded from other sources.

“The Mayor’s proposal drastically expanded funding for road maintenance,” Cecelia Black, an organizer with Disability Rights Washington’s Disability Mobility Initiative told The Urbanist. “And I don’t think anybody is arguing that our roads don’t need to be maintained. But you know, the levy sets the goal of filling every pothole [reported] within 72 hours. And then sets a goal of completing all missing sidewalks in 400 years.”

“Even just maintaining what we already are spending, that is just grossly inadequate and pretty offensive to any person in Seattle trying to walk,” Black said. “Because we have 11,000 missing blocks without sidewalks, and so when you say we’re going to build like 20-30 blocks of sidewalks a year — we would never do that with road infrastructure.”

Seattle’s missing sidewalk network network can be divided into two categories. Arterial streets lack sidewalks on around 1,800 blocks, or 14% of the entire network. Arterials are generally high-traffic corridors where the businesses and services are located and where Metro bus service often runs. Adding sidewalks to an arterial is generally the most expensive; individual designs to manage drainage and curb ramp access all add costs. On non-arterial streets, or side streets that are generally lower traffic with more residential land use, nearly a full third of the network is missing, or close to 12,000 blocks of sidewalks.

Five years ago, even 250 blocks over the life of a levy looked like it may be a heavy lift. The first draft of the 2015 Move Seattle levy only included 100 blocks of new sidewalks, a number that was increased to 150 blocks by the time the proposal was sent to the Seattle City Council, with a promise to fill in “75% of the gaps on priority transit corridors.” 150 blocks is what voters saw when they sent in their ballots that November, approving the levy by 17 points. But then Mayor Ed Murray’s administration upped the goal to 250, hoping to leverage the idea of building lower cost sidewalks on neighborhood streets without full curb and gutter treatment, filling in the missing sidewalk network at a faster pace.

In 2018, SDOT undertook the high-profile “reset” of the Move Seattle Levy and assessed whether the goal could actually be achieved, concluding that the full 250 blocks would only be achievable if the city built less than 150 blocks of permanent concrete sidewalks. Thanks to added funding in the interim, SDOT is now on track to finish the term of the levy with those 150 blocks of concrete sidewalks and 100 low-cost pathways.

But now 250 blocks is the seen as the new baseline. More than any other topic apart from filling potholes, the idea of filling in the missing sidewalk network has captivated several members of the brand new city council, likely in part because sidewalk construction doesn’t foster as much debate as other topics in transportation like calming traffic on busy streets or taking away space from general purpose traffic.

“Alarming stat, 27% [of blocks] missing sidewalks in the city — 27%! — which is totally unacceptable,” Rob Saka, new chair of the council’s transportation committee, said at an event at the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce early this month. “Adding new sidewalks will significantly help us achieve our climate goals, our safety goals, our ADA compliance goals. It’s what we can do to live up to our economic vitality goals. It ticks so many boxes. And again, importantly, it makes a difference in people’s everyday lives.”

“Part of our challenge is sidewalk construction has just continued to increase exponentially — it’s so much more expensive now that sidewalks can cost up to $800,000 for a block face,” SDOT’s Dan Anderson, one of the project leads on the levy proposal, told the Seattle school traffic safety committee this month. “And so what we’re looking at is how to do the most. And again, this is one of those […] items that when we talk with pedestrian and disability advocates, we all agree we could easily do a billion dollars in sidewalk construction [and] repair. But it’s at the cost of doing all the other work too. So we’re really trying to be laser focused on our planning [for] those arterials where we’re near schools, transit, bus stops.”

When the city council assembles as a group of nine for its first select committee meeting to discuss the levy proposal in early May, it’s clear the issue of sidewalks will be front and center. The question at this point isn’t whether more will get invested in sidewalks, but how much more.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.