Last week, Mayor Bruce Harrell released an initial proposal for a transportation levy that would provide eight years of dedicated funding to the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) and take the place of the expiring Move Seattle Levy. The $1.35 billion proposal, which would largely replicate Move Seattle and only increase the total funding per year by around 10% after accounting for inflation, disappointed many advocates who want the City to do much more to make progress on its climate, safety, mobility, and livability goals.

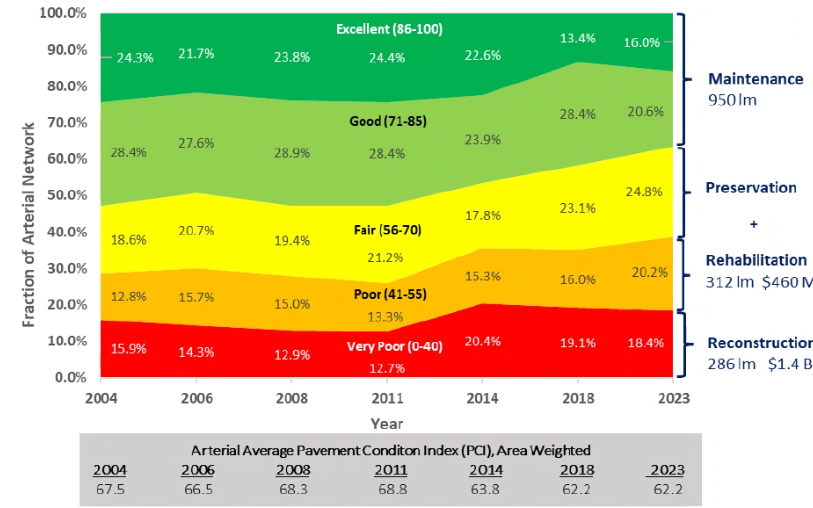

While much of the attention was on the total price tag, what individual projects get funded will also shape Seattle residents’ perceptions of the overall package. The single largest line-item set to be funded, $423 million in major street maintenance, clearly reflects a “back to basics” approach from the Harrell Administration and the fact that the city is continuing to fall behind on maintaining its arterial road network. Despite spending nearly $300 million on arterial maintenance and preservation over the past eight years, the percentage of arterials in “fair” condition or worse increased by nearly 10 percentage points. With such a sprawling street network, the best that Move Seattle 2.0 could likely achieve is to tread water.

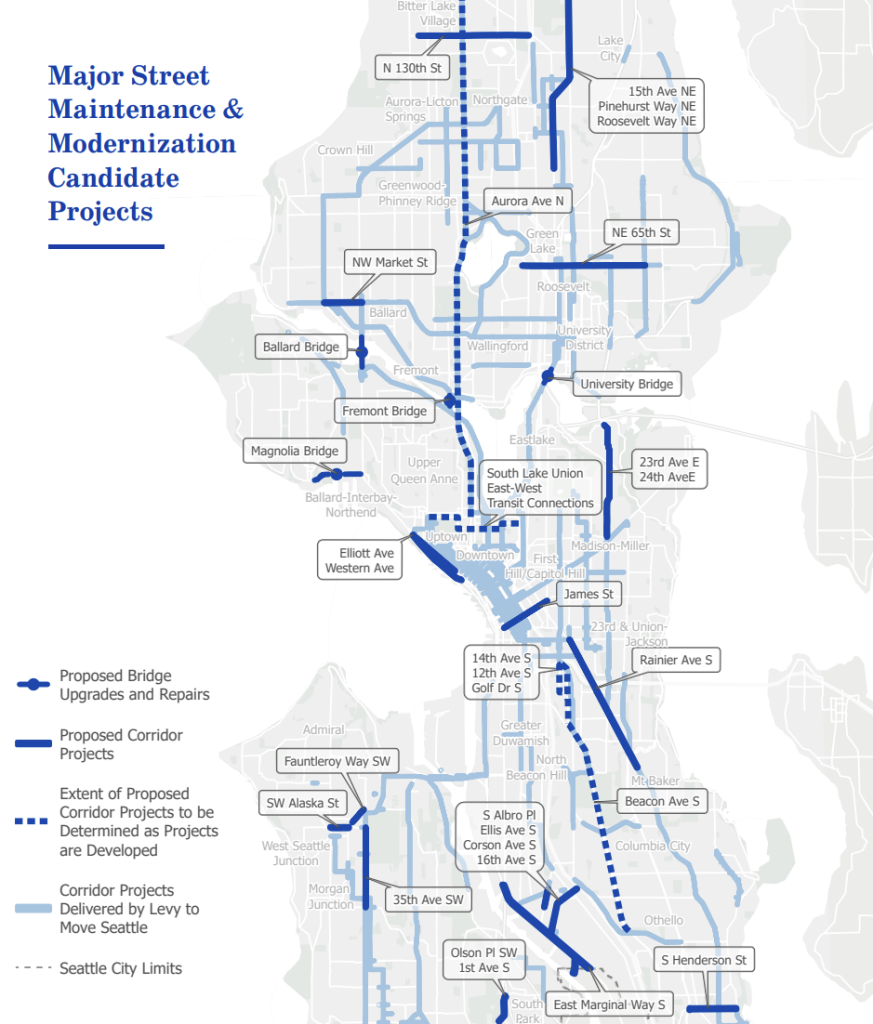

But the 15 corridor projects proposed also offer big opportunities for the city to be able to make progress on safety and transit reliability while doing the work to maintain those streets. The nearly half-billion proposed investment from 2025 to 2032 is separate from the $107 million proposed to fund direct safety improvements or the $97 million set to fund bike facilities, including a pledge to add more substantial barriers to 30% of the existing bike lanes across the city. And Seattle’s Complete Streets ordinance requires the city evaluate major repaving projects for opportunities to add bike facilities, safety improvements, and — as of last year — sufficient sidewalk facilities.

The levy is still in the draft stage, with a survey open until April 26, but here are the specific corridors that SDOT is saying they’d like to target, and which improvements are likely to come with each one.

Rainier Avenue S

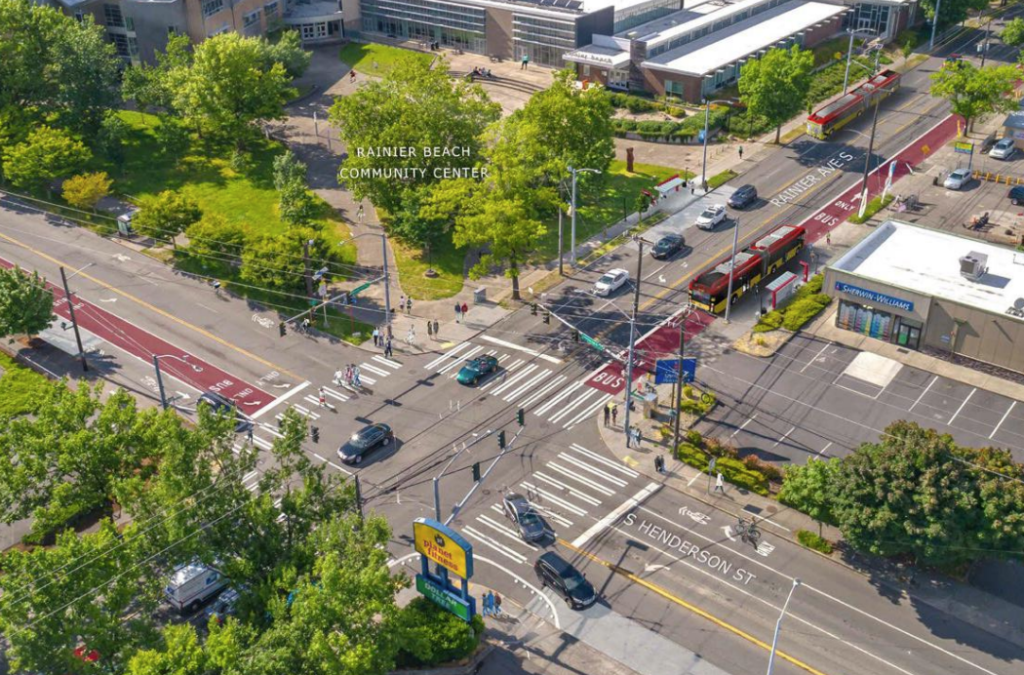

One of the highest-profile projects the new levy is set to fund is a repaving of the busiest segment of Rainier Avenue S, north of Mount Baker. With the levy also proposing matching funds to get the RapidRide R Line back on track, upgrading the current Route 7 — Seattle’s busiest non-RapidRide bus route — the repaving work will be a big component of the project as well.

But will the city also take advantage of the opportunity to connect the Rainier Valley with Downtown via the flattest, most-direct route and add bike facilities on Rainier Avenue? Right now SDOT just says “evaluation” of protected bike lanes is what’s on the table. Seattle’s brand new 20-year transportation plan calls for the corridor to be evaluated for a game-changing “catalyst” project, which presumably would look pretty similar to the Accessible Mount Baker plan that’s been sitting on a shelf despite Councilmember Bruce Harrell specifically amending it into the Move Seattle Levy in 2015, but so far there aren’t any signs of a serious look at corridor-wide transformation.

The project list also includes S Henderson Street. Currently, the Route 7 doesn’t directly connect with Rainier Beach Station at MLK Jr Way S and S Henderson, but Metro’s plans for the RapidRide R include that connection, with planned bus priority on Henderson. Currently SDOT is in the middle of a visioning process with community members around the future of S Henderson Street, but the department has already announced plans to build a two-way protected bike lane on the north side of S Henderson Street next year to connect the Chief Sealth trail with the three public schools in the area.

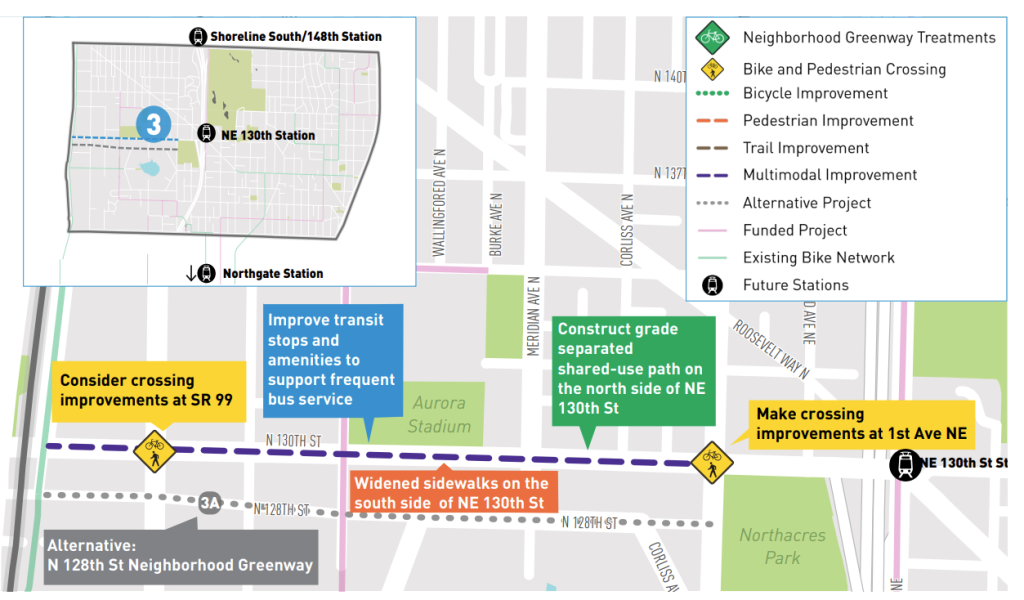

N 130th Street

In what’s probably the biggest overlap the levy proposes with the (largely status quo-oriented) One Seattle Comprehensive Plan, the proposed levy targets investments around N 130th Street, the location of a new planned urban center around a coming infill light rail station set to open in 2026 — a few years after the rest of the Lynnwood Link.

With SDOT already working on a project aimed at improving mobility east of I-5, the repaving project is an opportunity to add a safe place for people to bike, upgrade sidewalks, and add transit priority to the corridor west of I-5 all the way to the other side of Aurora Avenue at 1st Avenue NW. The 2021 mobility study on station access identified a shared-use path on the north side of N 130th Street, likely setting up a situation where someone travelling the entire length of the corridor would have to cross the street multiple times. That’s a tradeoff that will likely to come up in the years ahead, but it’s absolutely essential that there be easier ways to get to the new NE 130th Street station without a car.

NW Market Street

It wouldn’t be a transportation levy without some element linked to the Burke-Gilman Trail’s Missing Link. With the original Shilshole Avenue NW route still embroiled in a legal battle, Dan Strauss has pushed forward the idea of putting the trail on Leary Way NW, which would require extending the trail’s existing stretch along NW Market Street further east through Ballard’s business district. Today the trail ends east of NW 24th Street. The 10% designs advanced to this point don’t seem to adhere to SDOT’s own design standards and don’t separate the bike facility from the sidewalk, a disappointing choice for the city’s busiest bike corridor. But the repaving of NW Market Street could offer an opportunity to think more broadly about how the corridor gets used.

35th Avenue SW

One of the busiest streets in West Seattle, “I-35” is also one of the most dangerous corridors. Nearly a decade ago, SDOT redesigned the street south of SW Morgan Street, reducing through traffic to one lane in each direction and adding a center turn lane. The change successfully reduced the most severe types of crashes and actually improved transit travel times. But in 2018, under a new Mayor, SDOT announced they wouldn’t be extending the rechannelization north of SW Morgan Street into the street’s busiest segment.

Saying no to any changes along that segment meant any potential reallocation of the street to add space for people biking was off the table, despite the street’s inclusion in the 2014 Bicycle Master Plan. But like on Rainier, SDOT says the project will just include an “evaluation of bike routes.”

Elliott Avenue / Western Avenue

For years, The Urbanist has been covering the fact that the full rebuild of the Seattle Waterfront, set to wrap up next year, failed to connect to the rest of the city’s bike network. A last-minute project to create an extension of the Alaskan Way trail to Myrtle Edwards Park starts construction later this year, but a connection to downtown remains unplanned and unfunded.

A repaving project along Elliott Avenue and Western Avenue, which operate as one-way couplets, is an opportunity to actually ensure that people riding up to Belltown from the waterfront aren’t dumped onto a paint bike lane that probably has a driver parked in it that dissolves into “sharrows” after another block. Ideally, any look at the two streets would consider converting them back to two-way operation to reduce driver speeds, but the new Elliott Way likely baked in the current configuration for a few more decades. However, there’s still a big opportunity for a street that could end up being the back door for a downtown public school at the Battery Street portal site.

The levy materials promise a repaving up to Thomas Street, though the Seattle Transportation Plan only calls for bike lanes to Broad Street. The important thing will be ensuring a connection to another facility, either on First Avenue or Third Avenue W near the pedestrian bridge across the BNSF tracks at Thomas Street.

Fauntleroy Way SW

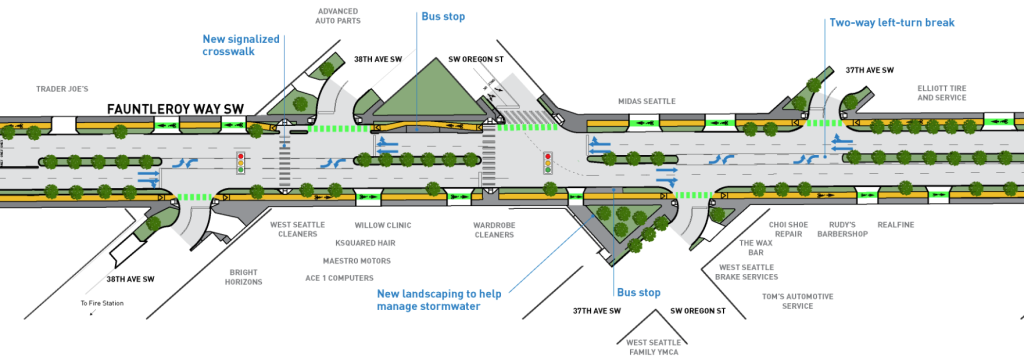

A full rebuild of the Fauntleroy Way corridor between the West Seattle Bridge and the Alaska Junction neighborhood was a central promise of the Move Seattle Levy. But even though it got to full design, the Durkan Administration put the project on hold during early planning stages for West Seattle’s light rail line to SoDo, and the funds earmarked in the levy were diverted elsewhere.

With Fauntleroy included in the streets that SDOT says are set to be repaved during the next levy, it’s not clear the extent to which any supplemental upgrades would be able to make up for the cancelled boulevard project, which was as much about “beautifying” the street with a center tree-lined median as it was about adding safety features and protected bike lanes. Sound Transit is still studying alternatives for its light rail alignment, and the City says the planned repaving is intended to “keep [the] roadway functional during light rail station construction and support future improvements.”

James Street

One of south Downtown’s primary east-west corridors, James Street is used by the Route 3 and 4 buses, which are frequently stuck in traffic drawn to the neighboring I-5 on-ramp. While a few blocks north RapidRide G Line buses will have dedicated space to get across the highway, so far no plans have been advanced to prioritize transit on James Street.

King County Metro’s 2021 “Speed and Reliability” report identified improvements like parking removal and a transit-only lane along James Street between 5th Avenue and 13th Avenue that could speed up travel times through the corridor, and a repaving project along the corridor could provide a opportunity to add them.

23rd and 24th Avenue E

This is another project likely to give transportation advocates déjà vu. The City recently wrapped up a “Vision Zero” project along the 23rd and 24th Avenue E corridor between Montlake and the Central District, during which a segment of the corridor was rechannelized, adding a center-turn lane in place of a southbound bus lane, but the busiest segment of the street through the heart of Montlake remained unchanged with only few tweaks at some intersections.

SDOT also just started construction on a very modest transit corridor project targeting the Route 48, but that project didn’t include a full evaluation of transit priority. With the nine-lane Montlake Boulevard just to the north fully opening by the end of this year, a repaving project is likely going to frustrate Montlake residents who are anxious for construction projects to be done, but it’s also a big opportunity to complete some unfinished business along the street and prioritize the modes we want to see more of in this critical corridor.

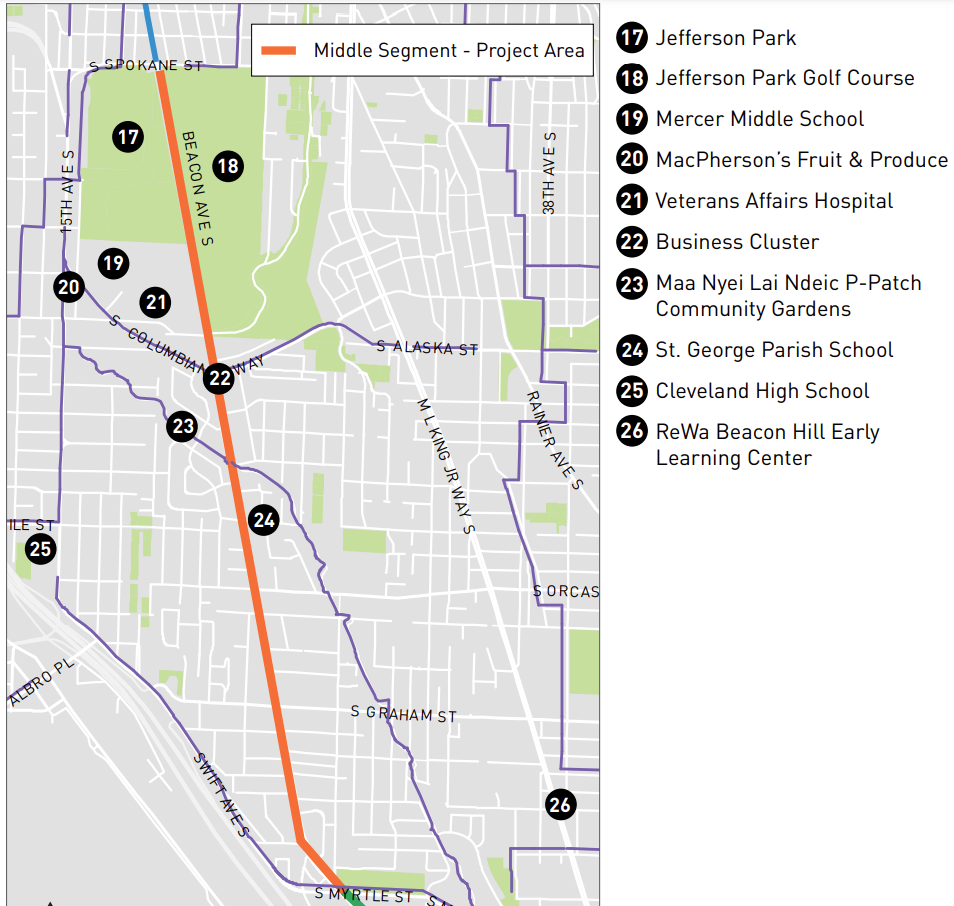

Beacon Avenue S

Along with the Route 7, the Route 36 is the only other King County Metro bus route the proposed levy currently promises significant investment in. This workhorse of a route includes a long stretch of Beacon Avenue S through Beacon Hill, which is included in on the potential list of corridors to see upgrades under this levy. (Notably, both the 7 and the 36 share a portion of their routes on S Jackson Street, where both routes experience significant delays, but there are no signs that the City is targeting that segment yet.)

Beacon Avenue S is also set to be the next phase of the Beacon Hill Bike Route project, connecting the segment planned north of Spokane Street with the existing bike facilities to the south including the Columbian Way bike lanes and the Chief Sealth trail. It’s been several years since SDOT proposed routing riders onto the center median trail down the middle of Beacon Avenue, a move that received a fair amount of pushback from bike advocates at the time. We should expect that issue to come up again as the city starts to talk about prioritizing the Route 36, but there’s no need to pit transit riders against people advocating for all-ages bike facilities on this critical corridor.

Overall, there’s wide agreement among stakeholders and advocates that the level of investment represented by the $1.35 billion levy would, at best, cause Seattle to tread water. Without ensuring that the $423 million set to be invested in maintenance projects goes the full distance in making sure access and safety improvements are fully baked in, the city would essentially be leaving money on the table. As the draft levy goes from a draft proposal to a council-amended one, how often this fact comes up is going to be a key issue to watch.

Take action

SDOT’s survey is open until April 26. The agency is hosting a series of outreach events around the city. Safe streets advocates are also hosting a rally dubbed “Transportation and Housing for a Healthy Future” on Saturday, April 20 at Jimi Hendrix Park starting at 2pm. Organizers note the event will include “performers, games, food, and speakers to celebrate Earth Day by pushing for more housing and better transportation.” Seattle Neighborhood Greenways is urging people to contact the mayor and city council and has an action network email campaign to make it easy.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.