Sound Transit faces tough decisions, and the uneasy and long-fraying regional alliance that holds the enterprise together could be in danger of imploding as the agency navigates another major financial crisis. The Sound Transit 3 (ST3) measure was approved by voters in 2016 to expand the system to 116 miles of light rail, but it’s in serious jeopardy. Board members seem to be retreating from tough decisions and entrenching deeper into their local political camps.

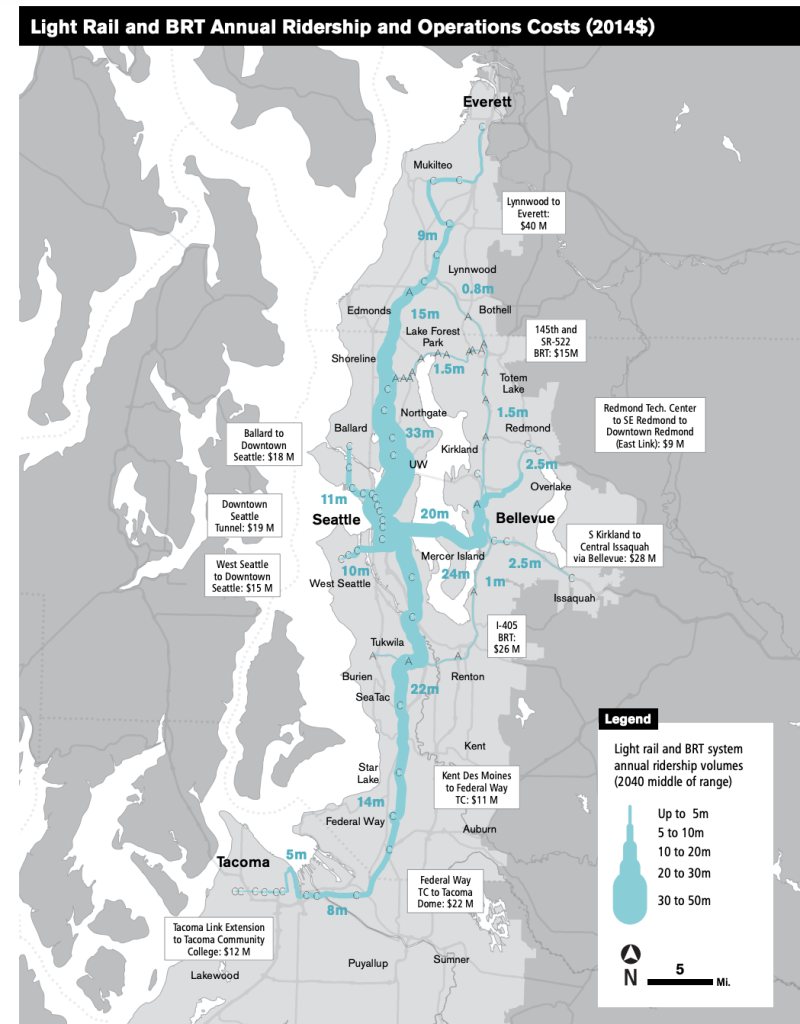

Last week, Sound Transit revealed a 20- to 30-billion-dollar shortfall for planned system expansion projects through 2046, an overrun of existing funding sources in the 20% to 25% range systemwide. This budget gap is driven not just by steep jumps in expected costs on capital projects when it comes to materials and labor, but also decreasing revenue.

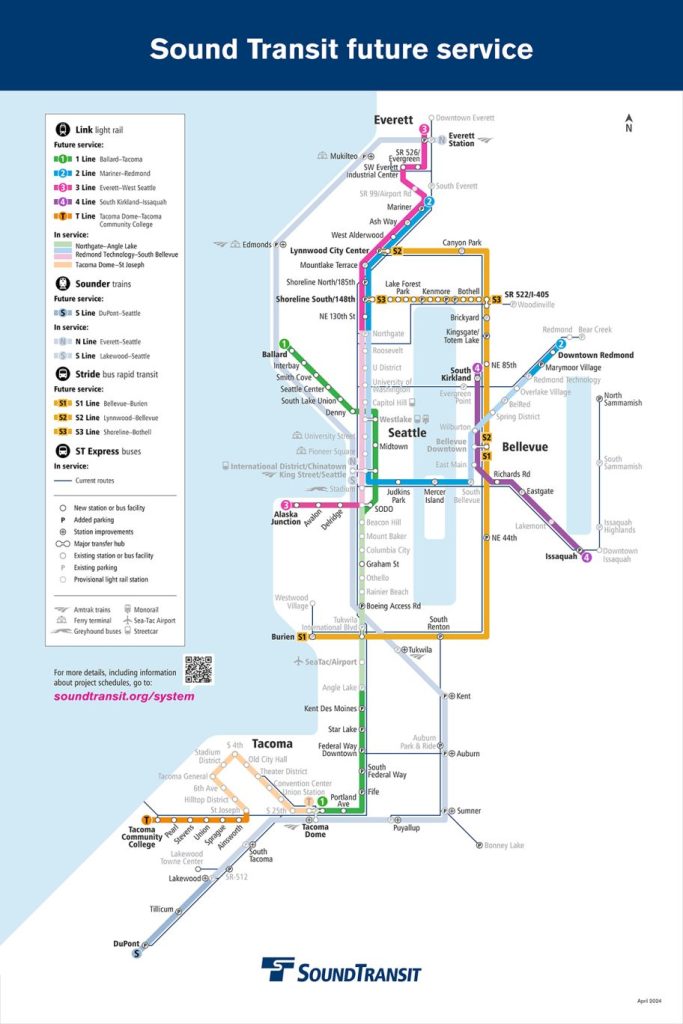

The busted budget has reopened old wounds over whether the agency’s top priority should be completing the 62-mile light rail “spine” from Tacoma to Everett or adding new urban lines in the denser core in and around Seattle. Tacoma is the county seat of Pierce County and Everett the county seat of Snohomish County which has made the spine the highest priority for board members from those counties.

On Tuesday, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell inserted himself into that debate in a big way with a Ballard press conference trumpeting Seattle’s light rail projects as priorities in their own right. While the event was billed as unveiling “actions to address increased Sound Transit expansion costs,” Harrell stopped short of proposing any new major cost-saving measures or revenue sources, as Ryan Packer noted.

That press event built on an amendment that Harrell proposed to the agency’s Enterprise Initiative board resolution, which narrowly succeeded in passing last week during Sound Transit Board of Directors meeting. Harrell’s amendment added “support future growth” as a factor to consider in that enterprise framework, which pledges to scour agency plans for savings so as to arrive at a balanced long-range financial plan by the end of 2026 — while still delivering expansion projects as soon as possible.

“Maintaining and growing ridership depends on connecting potential riders to their homes, jobs, schools, special events, and other activities,” Harrell’s added motion item begins, seemingly innocuously. “Aligning our investments with current land use and future growth will accrue benefits to the region’s economic, environmental, and equity goals. The region’s transit riders and voters have entrusted Sound Transit with their ridership and tax dollars and the investments that we prioritize should engender broad future support for the system’s operations, maintenance, and expansion.”

The amendment passed in an 8-6 vote with four members of 18-member board absent. Among those absent was Pierce County Executive Ryan Mello, who is likely a vote for putting the suburban spine first, given his geographic loyalties and past statements. Renton City Councilmember Ed Prince, Redmond Mayor Angela Birney, and state Transportation Secretary Julie Meredith were also absent from the vote.

Once Sound Transit has finished its “enterprise” framework and produced its cost-benefit analysis, board members will ultimately be forced to make their ultimate priorities known. The vote likely would be close. Board members are weighted by population and King County members compose a majority of the board due to its population. Of the 18 members, 10 are from King County, four hail from Pierce County, three are from Snohomish, and the final member is the State Secretary of Transportation.

Theoretically, it should be straightforward for King County to get its way on the board, but it’s rarely straightforward in practice. For starters, not all King County members see putting Seattle first as in their interest, even though the spine already will reach end to end in King County after Federal Way Link opens in December. For example, King County Councilmember Pete von Reichbauer voted with the Pierce County delegation on Harrell’s amendment, and Auburn Mayor Nancy Backus expressed that finishing the spine was her top priority even as she voted for Harrell’s amendment.

In fact, Harrell’s showy press conference and amendment might have more to do with his own impulse toward political self preservation, after underperforming in the recent primary election. He faces a strong progressive challenge from Transit Riders Union head Katie Wilson, who surpassed 50% and grabbed a nearly 10-point lead in the primary. (The Urbanist Elections Committee, on which I serve, endorsed Wilson.)

Wilson’s transit bonafides are obvious after more than a decade leading a transit advocacy organization that has scored big wins. Harrell’s are less obvious after projects have slipped increasingly behind schedule under his watch, while he did little — at least until a last-minute election season cram session.

While Harrell’s amendment passed, it clearly ruffled feathers in the process. It’s not clear he would have the votes or the relationships to get them once the agency’s board has to turn the enterprise initiative into a revised plan and schedule of project openings.

Some suburban board members raised concerns that Harrell was weighting the scale in favor of Seattle. Granted, some felt no qualms about weighting the scales in favor of their projects. Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin gladly admitted that she would delay Seattle projects to accelerate completing the spine when KOMO’s Chris Daniels put the question.

The particular project generating the most debate was Ballard Link, which is the agency’s most expensive undertaking since it adds the most stations and is slated to construct a second tunnel in Downtown Seattle. King County Councilmember and Systems Expansion Chair Claudia Balducci proposed that the agency study a redesign of the Ballard line to use the existing tunnel in order to curb costs.

While costly, the agency has projected that second tunnel could also be essential to ensuring smooth operations and meeting future ridership needs since running all three of its primary light rail lines through the same existing transit tunnel could lead to crowding, delays, and the potential for the entire network to become gridlocked during outages or maintenance work in that tunnel — which could constitute a single point of failure for the entire network with no viable alternatives in the “no new tunnel” scenario. That clear systemwide benefit had been the agency’s logic for sharing costs for that tunnel across the agency’s five subareas.

Balducci acknowledged these tradeoffs, but argued it would be a useful option to have on the table should others prove even more unpalatable. Harrell has expressed willingness to at least study the idea.

With the new tunnel, agency projections place Ballard Link as the highest ridership addition to the system, by far. The line would attract between 132,000 and 173,000 daily riders by 2042, according to the agency’s draft Environmental Impact Statement. Even with its high upfront cost, it leads the way in lowest cost per rider gained.

After a series of planning delays, Sound Transit latest timeline, which is likely to change pending the enterprise overhaul, would open West Seattle Link by 2032 and Ballard Link by 2039. Meanwhile, the Tacoma Dome Link Extension, after its own set of delays, is targeted for 2035 and a full opening of Everett Link is tabbed for 2041 — though the agency hoped a phased opening would allow it to reach Paine Field sooner.

At least one board member floated the idea of tabling West Seattle Link due to rising costs at a May board retreat — in hopes of avoiding delays on their own projects. Until Ballard Link is completed, West Seattle Link is set to operate as a truncated stub line with transfers forced in SoDo. The line will be less useful and convenient for riders under that interim service arrangement, but many would likely take it over no train at all.

While Harrell framed his proposal last week as a “very friendly amendment,” Everett Mayor Franklin argued it went beyond a friendly amendment and bordered on favoritism for Seattle.

“As Boardmember Backus said that we have to prioritize the spine that has been our commitment since the very beginning,” Franklin said. “And I think the interpretation of the spine that the majority of the region would see is the spine between Everett and Tacoma from Pierce to Snohomish County all the way to complete the system. I think that this does risk favoring Seattle.”

Franklin granted that Seattle was growing fast, but she argued its faster growth was propped up by being among the first cities to get light rail when Link service first launched in 2009.

“And I will say Seattle is growing. So is Everett,” Franklin said. “But of course, a larger jurisdiction grows much faster, and as you get the transit in that larger jurisdiction first, it also supports that growth. So, for us to serve the populations that desperately rely on public transportation that can’t afford to live in Seattle, we have to complete that spine.”

Everett’s population has been essentially flat over the last two years, according to state estimates, and it’s up about 4,000 residents since 2020.

Breaking from most non-King County boardmembers, Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers voted for Harrell’s amendment. Somers chairs the Sound Transit Board, an honor which rotates between the three county executives on the board. Somers said he wasn’t intimidated by factoring in growth and access to job centers because Everett is home to a major Boeing manufacturing plant that rivals other employment centers in economic output.

Serving the massive Boeing factory is also the main reason why Everett Link hooks over to Paine Field before heading to Downtown Everett, adding an extra four minutes to each journey over a more direct route along SR 99, where more residential density exists. If the priority is getting to Everett as quickly as possible, Sound Transit’s spine has an unfortunate case of scoliosis. The Paine Field station would attract fairly anemic ridership, according to agency projections, and it would cost much more than alternatives, due to the added length.

Tastes like SWUGA

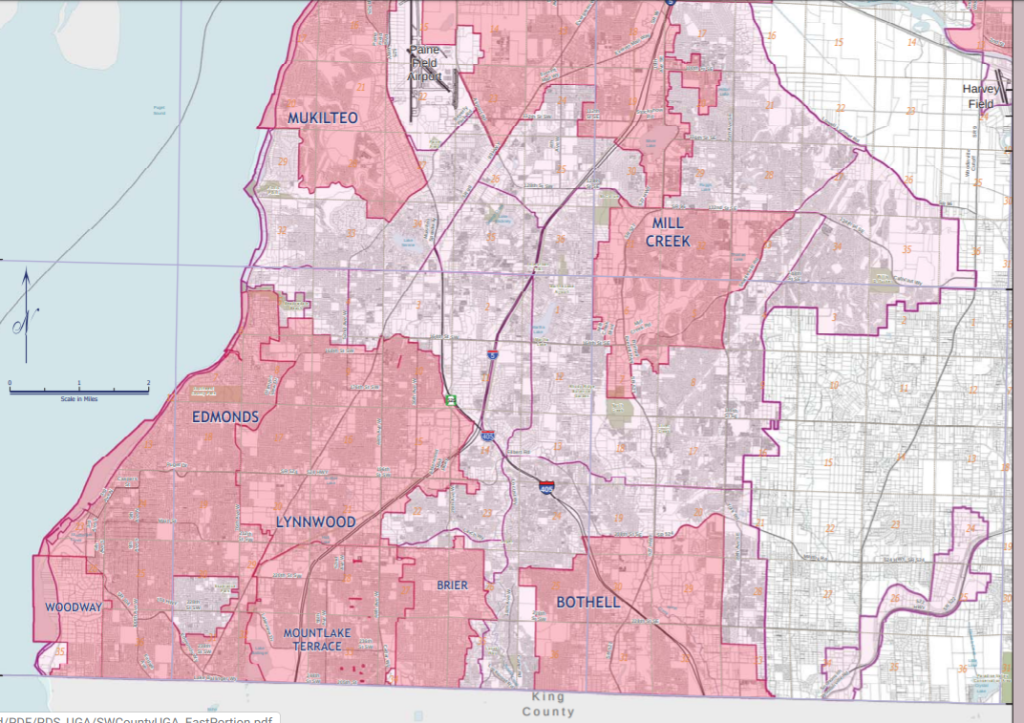

Somers also embarked upon a novel defense of his county’s ridership potential based on the unheralded density of Snohomish County’s Southwest Urban Growth Area (or SWUGA in planning shorthand).

Somers portrayed the Southwest Urban Growth Area as rivaling Seattle as a population center, although his cited population statistics were deeply inaccurate. Unincorporated SWUGA fills in the gaps between Everett and its neighboring incorporated cities to the south, up to the urban growth boundary to the east.

“Our Southwest Urban Growth Area in the county is urban,” Somers said. “It has been developed urban, but it’s never been incorporated in a city. And my staff tells me, if it incorporated today, it would be the third largest city in the state and has a higher residential population density than the city of Seattle, which is kind of amazing, because drive by it, you don’t recognize that. But more people per square inch than much of the rest of the state.”

The population of unincorporated Southwest Urban Growth Area is roughly 4,600 per square mile, whereas Seattle’s population density is more than double that. Seattle’s population density surpassed 9,700 with the latest state population estimates, which saw Seattle grow past 800,000 in total population. The Emerald City is quickly approaching 10,000 per square mile

On the other hand, unincorporated SWUGA is denser than Everett, which has fewer than 3,500 residents per square mile.

The Everett Link Extension will add two stations fully within unincorporated SWUGA — at Ash Way and Mariner park and rides. A third SWUGA station at SR 99 and Airport Road is provisional and unlikely to move forward barring finances improving dramatically or the board selecting a new route. Arguably, the provisional Airport Road station is Everett Link’s most promising, since it intercepts the Swift Blue Line bus rapid transit line and serves an area with existing density and high growth potential.

A way forward?

The sparring over the past week illustrates the fact that, despite a pledge to prioritize regionalism, the way forward seems incredibly zero-sum. Effectively, the agency is doing what it usually does, which is forging ahead without any major modifications in effect and hoping that solutions emerge at a later date. The enterprise initiative could succeed in forcing a paradigm shift, but so far the pattern is very familiar.

Sound Transit has not released new cost estimates for Ballard Link after the bout of inflation tied to the pandemic and Trump’s trade war, which are hitting construction projects especially hard. The last publicly available estimate put the 10-station line around $11 billion in 2023 dollars, although that figure is sure to be revised upward significantly.

Quicker permits and more efficient contracting and planning process are unlikely to solve the bulk of agency’s larger $20-to-30 billion hole — though it’s certainty wise to get more efficient where they can. Hiring deputy CEO Terri Mestas specifically to focus on improving capital project delivery was a step in the right direction. But the headwinds Sound Transit are facing are enormous, and include the very real risk that a Republican federal administration would delay or block transit grants altogether.

Skipping Seattle’s second downtown tunnel is the only solution on the table that maybe could be on the scale to solve the budget hole without resorting to massive delays. However, it also may simply be untenable for an operations standpoint, preventing the agency from serving the ridership the network was built to serve — originally the system was projected to reach 600,000 daily riders once ST3 was built out. Not all of them would travel through downtown Seattle, but that is where demand is the highest.

And since all three lines would travel through downtown Seattle, downtown obstructions or delays would ripple across the entire system, delaying trains for nearly everyone.

Another challenge for a ‘use the existing downtown tunnel’ scenario is how to connect the Ballard Line.

One option: a junction to tie in to the existing tunnel near Westlake Station and continue south as originally planned. This could prove incredibly challenging both from an engineering and operational standpoint to drill a new tunnel into an existing tunnel while avoiding disruptions to existing service to the extent possible (read: a lot of disruptions). It also could be quite expensive to build, reducing some of the expected savings.

The other option is make it a stub line forcing a transfer at Westlake Station. Easier from an engineering standpoint, but the flow of riders transferring from the Ballard Line would exacerbate crowding issues at Westlake Station, and trains could already be near crush loads at this point in the system, especially if Sound Transit has to cut frequencies to make the single tunnel plan work. It could be a recipe for an ongoing operations nightmare. Hopefully, Sound Transit’s analysis can shed some light on the probability this becomes a huge issue.

The same fork in the road exists for West Seattle Link without a second downtown tunnel. Tying in the new line to the existing tracks may be easier to engineer in the at-grade section in SoDo, but there’s no guarantees. On the other hand, a West Seattle stub line terminating in SoDo would be much worse for rider convenience than a Ballard stub that at least would make it to Westlake in Downtown, close to many destinations. SoDo Station is next to nary a major destination, meanwhile the county would likely still lose a major bus corridor in the SoDo E3 busway while getting less benefit in the process.

Even if the “complete the spine” crowd were to get their way and delay or cancel Seattle projects to speed up spine delivery, it’s not clear the spine could handle ridership demand without a second tunnel. If capacity did end up being deficient, Pierce and Snohomish counties would end up with shiny new stations, but not enough trains to handle the load — more the appearance of a functioning light rail network than actually having one. Major destinations like Seattle Center, South Lake Union, and Ballard not being tied into the system would be detrimental to riders all over the region, worsening commutes and sapping ridership — though probably not enough to alleviate the capacity issue.

No easy choices exist for ST3 — at least that have been identified so far. Boardmembers naturally want their local projects to happen on schedule and in the full form promised to voters. But short-sighted parochial squabbles do not appear to be getting us any closer to a real solution. Something has to give — barring a king’s ransom parachuting in to paper over the gap.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.