Joe Mayes waited at the Route 7 bus stop on Rainier Avenue S and Mt. Baker Boulevard on New Year’s Day, casually greeting people as they crossed the street in his direction. Mayes, 54, grew up in the Central Area before his family moved to Skyway, an unincorporated part of King County just south of Seattle–he knows everybody.

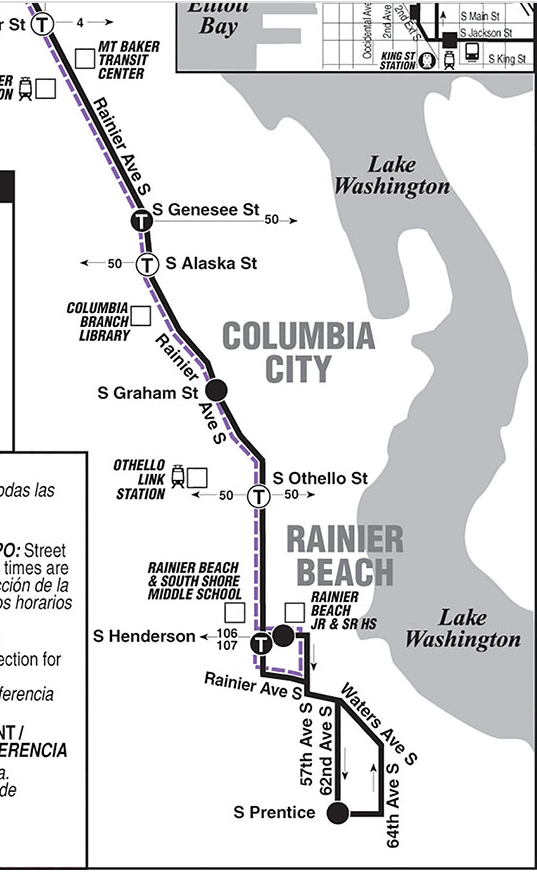

Mayes takes the 7 practically every day, as do roughly 11,000 daily riders by Metro’s tally from last year. He travels south through the “Prentice Loop,” a square that bends down South Prentice Street past a single-family home festooned with plastic pink flamingos, up 64th Avenue S and around Waters Avenue S.

It’s more reliable than Route 106, which runs down Renton Avenue S, Mayes said.

However, prior to the coronavirus pandemic, Route 7 and its Prentice loop were not long for this world.

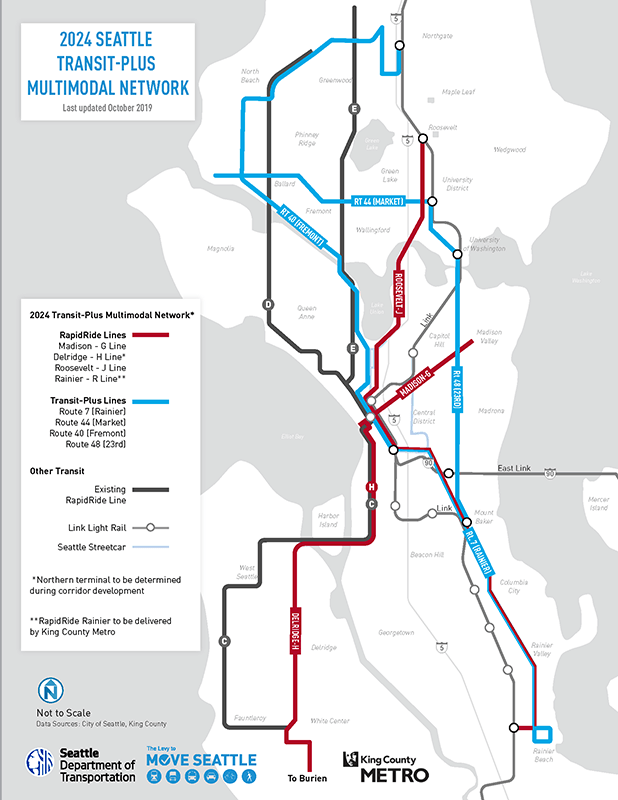

King County Metro planned to eliminate the route–which connects the core of Seattle to the South End–in favor of RapidRide R, a streamlined route that was part of a planned extension of the RapidRide system. Metro was forced to backtrack on plans, cutting the proposed expansion down to four routes: Delridge (H), Madison (G), and Eastlake (J) and RapidRide I, a line connecting Renton, Kent, and Auburn. Of the seven RapidRide lines promised in Seattle’s 2015 Move Seattle Levy only three remain, all are on delayed timelines, and Eastlake’s Route 70 upgrade is in an abridged form, no longer reaching Roosevelt. RapidRide R was only the latest cut.

For Mayes and other Route 7 loyalists, the cut was no loss at all.

“It’s a historic landmark, they should keep that bus forever,” Mayes said.

The plan to replace the 7 with RapidRide R is outlined in Metro Connects, a long-term vision for the future of transit in King County first adopted in 2017. The plan is being revised and is expected to be transmitted to the King County Council this summer for action in the fall, according to Metro. However, changes to Route 7 require money, a commodity that the county is finding in short supply. Sales tax revenues bottomed out as a result of the coronavirus pandemic and associated shutdowns. In budget documents, King County estimated that it would bring in $200 million less in sales tax revenues over two years, jeopardizing spending priorities like transit. To make matters worse, federal grants for transit (for which RapidRide projects compete) slowed to a trickle under the Trump administration.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is moving ahead with other corridor improvements, including some northbound business access and transit (BAT) lanes. SDOT is also upgrading some Rainier Avenue sidewalks after advocates pushed back against cuts in the latest budget.

Metro placed RapidRide R on an indefinite hold in fall 2020, although the agency said in a presentation that it expects to resume development when revenue rebounds. The design is at the “preferred concept” phase, and the final design for the proposed route has not been approved.

“Preferred,” of course, depends on who you ask.

In his column “It’s Complicated,” bus driver and columnist for The Urbanist Nathan Vass wrote that RapidRides are associated with gentrification, in part because it’s difficult to gather representative public opinion, even on something as influential as transit.

That’s not entirely Metro’s fault, Vass noted.

“You just have to be out there, feeling the pulse of the place, how it shifts and speaks in years,” Vass wrote. “Can those who’ve suffered at the hands of authority be expected to give their honest feedback to authorities on command, on terms not set by them?”

Metro has held open houses, tabling, interviews with community organizations and online town halls, among other forms of outreach. But the postponement of the plans to replace the 7 with a RapidRide elicited “silent relief,” Vass wrote.

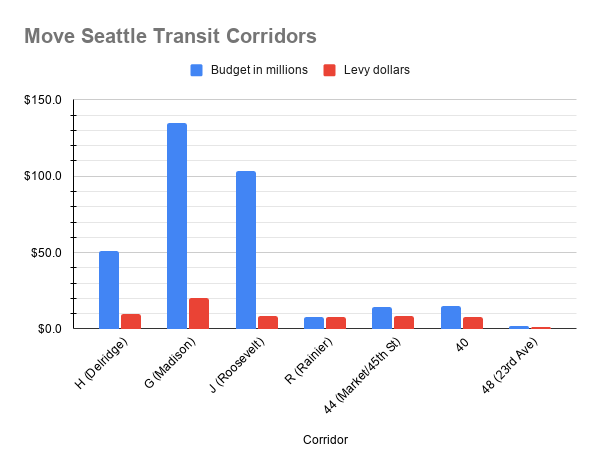

Move Seattle Transit-Plus Corridors after 2020 Reset

| RapidRide Corridor | 1st Revision | 2018 Reset Date | 2020 Covid Reset | Budget in millions | Existing Route | 2016 Daily Ridership | Platform Hours (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G (Madison) | 2021 | 2021 | 2024 | $134.7 | 12 | 3,300 | 84 |

| H (Delridge) | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | $51.1 | 120 | 8,600 | 226 |

| R (Rainier) | 2021 | cut | ? | $7.5 | 7 | 10,800 | 255 |

| J (Roosevelt) | 2021 | 2024 | 2024 | $103.4 | 70 | 7,500 | 182 |

| Market/45th St | 2022 | cut | 2024 | $14.6 | 44 | 8,400 | 167 |

| Fremont | 2023 | cut | 2024 | $15.2 | 40 | 11,400 | 284 |

| E 23rd Ave | 2024 | cut | ? | $2.1 | 48 | 5,500 | 183 |

| Move Seattle Transit-Plus portfolio | $328.6 | 47,100 |

Part of the strength of Route 7 is its network of local stops that make the route more convenient to more people.

Replacing the 7 with the RapidRide R is the wrong way to go for the community and for the transit network, said Andrew Kidde, chair of the Rainier Valley Greenways.

Much of the Rainier Valley community “doesn’t really want the RapidRide R,” Kidde said, adding that they don’t like the reduction in the number of stops, the removal of the Prentice loop at the south end of the route nor the RapidRide-style fare enforcement where officers check payment on the bus. Advocates fear that the new fare enforcement will result in disproportionate enforcement against people of color.

A RapidRide would reduce the number of stops on the route, which would make it harder for people who currently rely on their local route. Rather than replacing the 7, Kidde believes Metro should add a RapidRide express on Rainier Avenue that goes all the way to Renton.

Serving working people with transit in King County is a huge challenge, Kidde said. Many working-class people have moved from Seattle to South King County as sky-high rents make it more difficult for people to afford living in the city. Operating buses between Seattle and King County’s low-density suburbs is expensive, Kidde noted, but a lack of transit to such neighborhoods makes workers in south King County vulnerable to “automobile dependence.” Automobile dependent people teeter on the edge of bankruptcy; one repair job for their vehicle could push them over.

The reduction in stops would make a difference to disabled people, too.

Asking people to travel farther to get to stops can limit who is able to take the bus, Anna Zivarts, director of the Disability Mobility Initiative with Disability Rights Washington, wrote in an email.

“A lot of the folks riding the 7 in my experience aren’t traveling downtown and are traveling to different points along Rainier, so the stop reduction is actually something that can make the bus less convenient,” Zivarts wrote in an email.

Although people have raised concerns about the RapidRide R, it was not the only line put on ice. Transit advocates were disappointed that the funding for the overall RapidRide expansion fell through. Katie Wilson, general secretary for the Transit Riders Union, wrote in an email that the organization was “not happy” with the delays RapidRide rollout, including the R.

However, without outside funding, it’s hard to see those budgets restored in the near future.

“Of course we hope a lot more federal transit aid will be forthcoming, and more support from the state legislature as well,” Wilson added.

While the Trump administration indulged in a Groundhog’s Day of “infrastructure week,” it’s possible that the Biden-Harris administration will be more amenable to transit investments, yet another layer of speculation for changes that could occur after Inauguration Day on January 20th.

In the meantime, the 7 trundles on.

Clarification: The Metro Connects plan began revisions in 2020, but changes are still in progress. The King County Council is expected to receive the plan in the summer for action in the fall.

Ashley Archibald

Ashley Archibald is the editor of Real Change News, a nonprofit journalism outlet covering economic and social justice issues in Seattle and beyond. She can be reached at editor [at] realchangenews.org and on Twitter at @AshleyA_RC.