When what is now downtown Bellingham was initially platted in the mid-1800s, it is likely that little consideration was given to parking. Mostly because cars did not exist in the mid-1800s. As automobiles became quintessential components of the American way of life by the 1920s when it killed off Bellingham’s streetcars, parking grew in importance. By the 1950’s, cars had become the area’s primary mode of transportation, and one by one, many of the business, apartments, churches and more which had constituted the core of the city were torn down to make way for car storage.

I have thought about this topic significantly while visiting my parents in Bellingham, and living with them for a time during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Walking through downtown I could see the marks on the sides of buildings where structures were demolished to make way for parking lots, in contrast to continuing sprawl on the outskirts of town. Paired with concurrent crises of affordability and climate change in the region, I sought to make sense of what was lost when so much space is instead dedicated to parking, and perhaps where the region’s nominally progressive political rhetoric has not fully matched with action on the ground.

The nomination form for the Downtown Bellingham Historic District notes how extensively the city was modified to accommodate cars. Interstate 5 was built in Bellingham with “numerous interchanges, more per capita than any other Washington city … State Street was particularly affected: as older buildings were torn down or destroyed by fire, they were replaced by parking lots … Downtown’s original walkable shopping district, centered on a three-block stretch of Magnolia, was gradually replaced by supermarkets on the periphery of downtown, or in the growing suburban areas.”

Parking is a fraught issue and frequently devolves into a chicken-egg discussion over whether incentives to reduce driving — faster and more frequent public transportation or the construction of affordable, walkable neighborhoods — should come before or after penalties such as increasing parking fees or reducing the amount of parking available overall.

There are several resources online which describe the issue better than I can, but the crux of the argument follows the same general outline. Parking facilities take up valuable land which otherwise could be used for more productive purposes such as businesses or housing, given that the average car is parked and dormant about 95% of the time. There are often far more parking spaces than cars (or homes for that matter) in any given area, which seems like a curious use of scarce land given the scale of the affordable housing crisis in the region. Dedicating that much space to cars over any other purpose prioritizes making driving convenient over any other mode of transportation, demolishes historic buildings to make way for parking, and results in sprawling, spread out development which destroys farmland and natural spaces. And finally, car dependency and urban sprawl is associated with all sorts of terrible things, like carbon emissions, climate change, traffic deaths and injuries, the replacement of farmland with tract homes, and all sorts of hidden costs, some of which will be discussed later in this article.

One could see much of this push-pull informally play out in online discussions over the introduction of paid parking to Fairhaven, the neighborhood surrounding Bellingham’s ferry terminal. But what does the specifics of the parking debate look like in Bellingham? Some map analysis can help us find out.

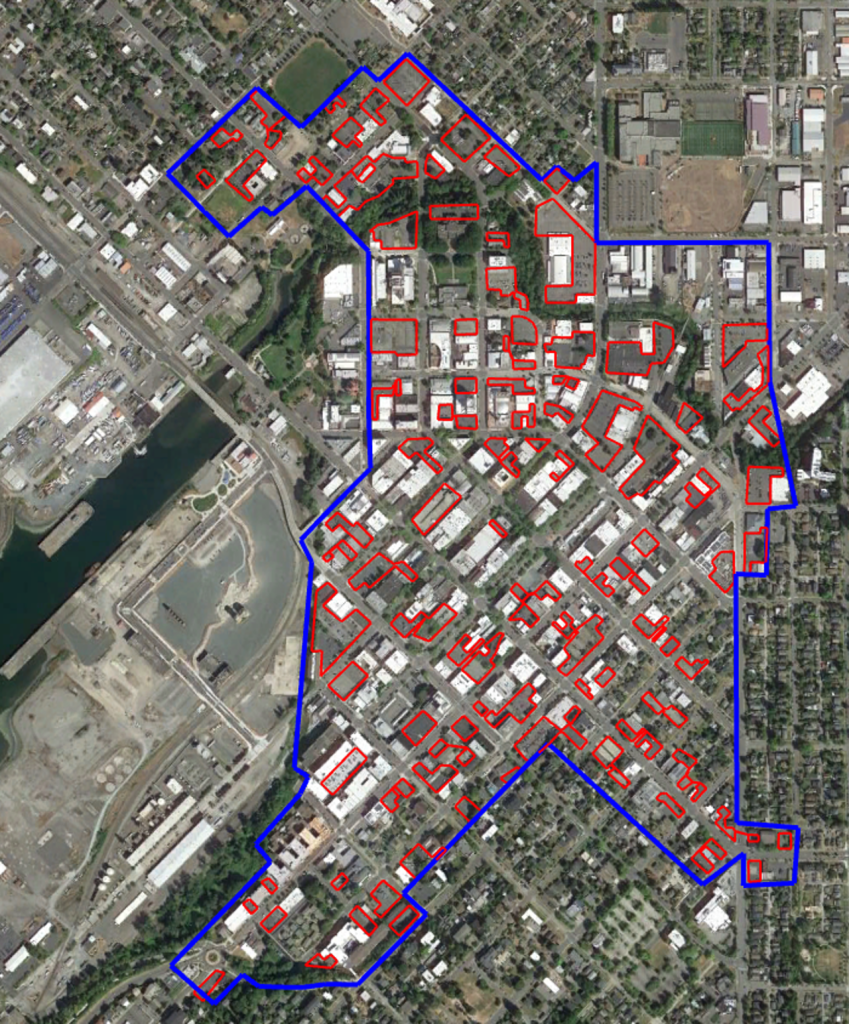

For simplicity’s sake, I limited my focus on the downtown area, more specifically the Downtown Urban Village District as defined by the municipal government in its adopted plan from 2014. Using Google Earth’s 3D Polygon tool, I traced out the area of downtown, as well as the area of parking lots within downtown. I excluded parking stalls used for holding uses essential for business operations like an auto repair yards and the downtown farmer’s market lot. (Note: While Bellingham does have a downtown parking inventory, it has not been updated since 2010.)

In all, the area of the downtown ‘urban village’ was calculated at 11,795,653 square feet (1,095,852 square meters), with an estimated 2,194,858 square feet (203,909 square meters) of buildable space dedicated to parking alone – equivalent to 18.61% of the entire downtown area, and almost certainly an undercount, as this figure excludes all on-street parking as well. Almost one-fifth of Bellingham’s downtown is dedicated to off-street parking.

With figures such as these, one begins to wonder what this space could be used for instead – what is missing from Bellingham due to this cornucopia of parking.

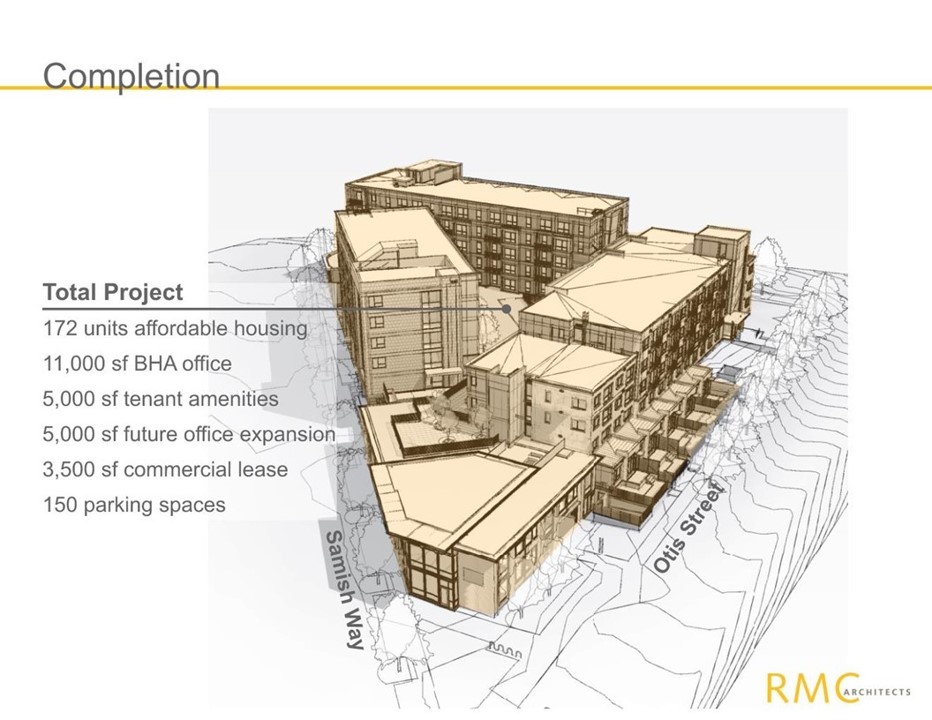

South of downtown, there is a project underway called Samish Commons, which once fully complete, seeks to redevelop a former motel site into 172 units of affordable, senior, accessible, and transitional housing, office space, as well as resident amenities such as green space. By superimposing copies of Samish Commons as infill onto downtown parking lots, the scale of alternative uses for parking downtown – mostly for housing and commerce – can be roughly estimated.

Occupying a footprint of about 43,755 square feet, the 2,194,858 square feet of surface parking in downtown Bellingham – still completely excluding on-street parking – is equivalent to 25.56 Samish Commons, or:

- 127,800 square feet (11,873 square meters) of resident amenities, such as courtyards, meeting rooms, etc.

- 4,396 units of housing, more than double the current number of units downtown (~2,000)

These figures underscore the true cost of parking, beyond fares, permits and fines. First, there the money put towards the construction and maintenance of parking facilities, which can range from “$20,000 for those on surface lots and can cost upward of $60,000 for underground garages” – costs which are often passed on in forms like higher rents. There is then the costs to society imposed by cars, including their immense expense to American families, greenhouse gas emissions (more from transportation than any other source in Washington state), and growing traumatic deaths and injury from traffic. And finally, demonstrated here, is the opportunity cost of parking: what could have been done with that land or those funds instead of storing cars.

The funds used to build and maintain parking instead could have been allocated to support public transit or community services. Instead of parking lots, the land could have been home to shops and apartments, which would provide places for people to live and generate property tax revenues far in excess of what parking fees could bring in.

To its credit, the City has recognized the importance of compact infill development rather than sprawl in natural areas or farmland, and has created a toolkit for developing upon vacant and underused land, such as surface parking. Indeed, a large part of the reason I created my own parking estimate, rather than using the 2010 parking inventory, was to account for the many developments which have been constructed atop of former parking lots.

Bellingham’s Infill Housing Toolkit is a section of municipal code which intends to apply a series of standards in the design and construction of infill housing, both to facilitate approval of designs and to promote compact, walkable development within already built-up areas. Containing preferred specifications for housing forms such as triplexes, townhomes, and courtyard houses, these forms are often referred to as the “missing middle” — more compact than detached houses, more spread out than a high-rise, preferred by many, yet often in short supply in many American cities.

Other places around the country have created similar guides, such as the Pre-Approved Plan Catalog in South Bend, Indiana, which contains sample floor plans, pre-approved by the city and ready to build, ranging from an accessory development unit to a six-unit apartment building. These kinds of tools can be helpful in speeding up the pace of development, especially in an environment where attempts to legalize the construction of something even as simple as a duplex can take years. Unfortunately, both the Toolkit in Bellingham and the Catalog in South Bend lack infill assistance for commercial or light industrial space, which would be pertinent for a heavily commercial area such as a downtown. For example, they both miss the most classic form of missing middle development — a building with working space on the first floor and apartments on top, like the Belcher family’s residence in Bob’s Burgers.

Nevertheless, the many asphalt pockmarks which still mark much of downtown, where buildings once stood, suggests that measures such as the Infill Toolkit have had a limited impact so far, and that more should be done, with an immediacy that recognizes the scale of the climate and affordability crises in the region. It is curious that the core of Bellingham, where most civic services are located and walking and public transit is most convenient, remains more sparse today than in the 1920s or 30s, when Bellingham’s population was about a third of its current population of just over 90,000.

Reducing the number of trips taken by car and increasing the amount of housing available in Bellingham are both imperative if the City is to be serious about achieving both its climate action and affordable housing goals. Replacing parking spaces with housing would work towards fulfilling both goals simultaneously.

It is written on the walls that many of these buildings used to have neighbors. Outlines here and paint there, once shielded from the elements, but now exposed after a demolition to make way for parking lots. This was a significant change to Bellingham, as was the case for most American cities. Another significant change must take place again, in one sense a return to the past, but also as an important step towards addressing the issues of the future, so that people will have more space to once again live in downtown Bellingham, and that the ghosts of buildings past be resurrected.

Austin Wu (Guest Contributor)

Austin Wu’s first introduction to urbanism was in third grade, when he first learned about the 1961 demolition of the downtown train station in favor of two parking garages in his midwestern hometown. For the past couple of years he has been a freelance writer on topics relating to local history, land use, and transportation, and has also previously worked on research and advocacy on road safety policy for the League of American Bicyclists, particularly on the impact of vehicular speeds on bicyclist and pedestrian safety. Follow him on Twitter, @theaustinwu, or on Mastodon @austwu@mastodon.social.