In the spring of 2020, downtown Seattle sat empty. A once bustling and growing core of tower cranes, thriving businesses, and active neighborhoods was now silent. Office workers were gone, and in the interim worked remotely, which soon became long-term preference. During the slow recovery, restaurants, retail, and transit all suffered, while office workers realized they could log in from home.

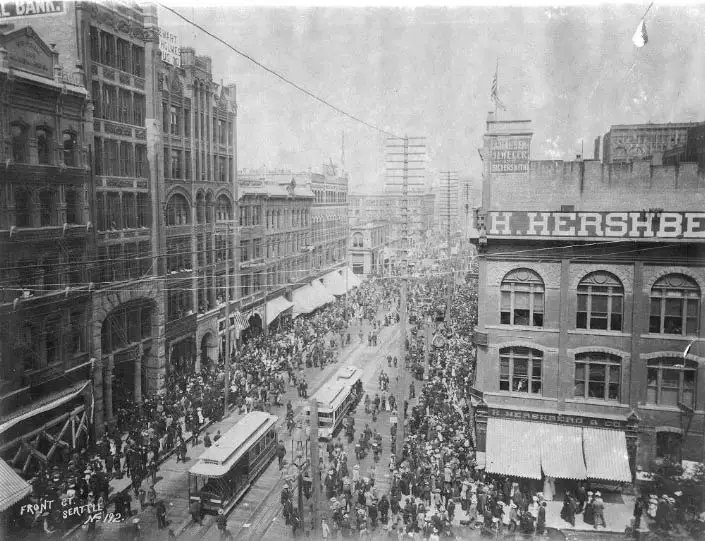

In the early days of our city, Seattle’s Downtown streets used to be full of people and commerce. We housed a lot of people in the core, because they didn’t have WiFi or a highway to buzz them out of town at five o’clock. After World War II, Americans subsidized the destruction of our cities, including Seattle. We plowed over vibrant urbanism and displaced thousands of people to get office commuters to work mostly by car. I-5 through Seattle began construction in 1967, displacing over 40,000 residents, and turned most downtown streets into freeway on- and off-ramps.

Cities like Seattle redesigned themselves with office commuters in mind. No longer designed around residents, downtowns became a central business district from nine to five, Monday through Friday. Downtown populations declined and cities relied on offices as the sole responsibility to support commerce, tax revenues, and transit ridership.

But in the last 20 years, Seattle was at the forefront of undoing these previous urban mistakes, with successful growth in the core until the pandemic upended all the momentum. With nearly 15% of the city’s population living in the 4% of land that makes up downtown, Seattle’s core is more suited for recovery than many other US cities. But this growth was still heavily reliant on office commuters, with over half the real estate dedicated to office space. With uncertainty that this lifestyle will return, what do we do now? Here is an Eight Point Plan to revitalize downtown Seattle, a plan that goes beyond filling storefronts with artists, changing the walk signal frequency, and putting out vibes of hope and desire.

1. Build Even More Housing

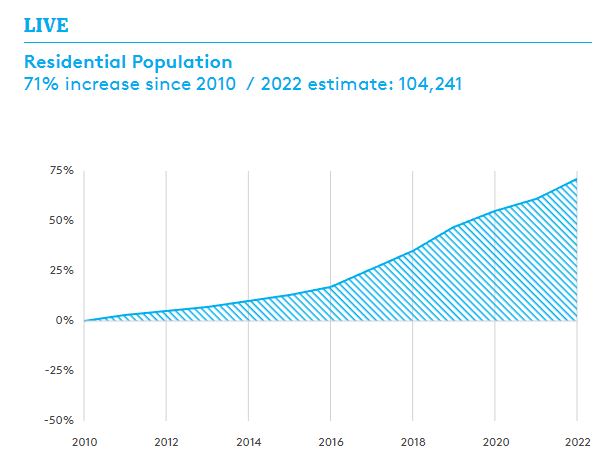

Downtown Seattle is already on solid footing when it comes to housing in the core. In the 1990’s and early 2000’s, the city encouraged downtown housing growth, which lead to its pre-pandemic urban renaissance. Downtown Seattle’s population is large, with about 100,000 people calling it home. It has even added residents since the pandemic.

Unfortunately, even with the residential population, the core’s urban fabric is designed for office commuters to swell the population three times — to 400,000 people — any given workday. With offices floating around 60% vacant, something must fill the gap of that foot traffic or more businesses will struggle.

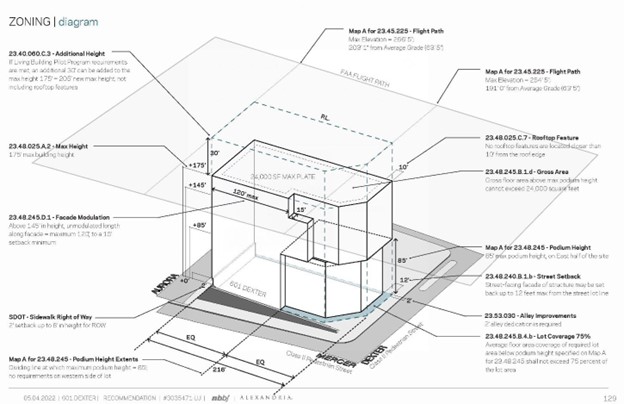

The answer is more housing. We need to look at ways to streamline permitting, encourage family sized units, discourage wonky zoning restrictions to housing, and subsidize methods to deliver homes downtown economically and quickly. Downtown already allows residential to be built throughout, so all we need is a little push to encourage it. Seattle needs to do away with regulations to floor plate sizes, tower separations, tower height limits and façade length limits, all things that our land use code does to limit how many homes we can build. There is no downside to adding and encouraging more homes downtown in this recovery, so why limit ourselves?

2. Redesign Downtown’s Streets

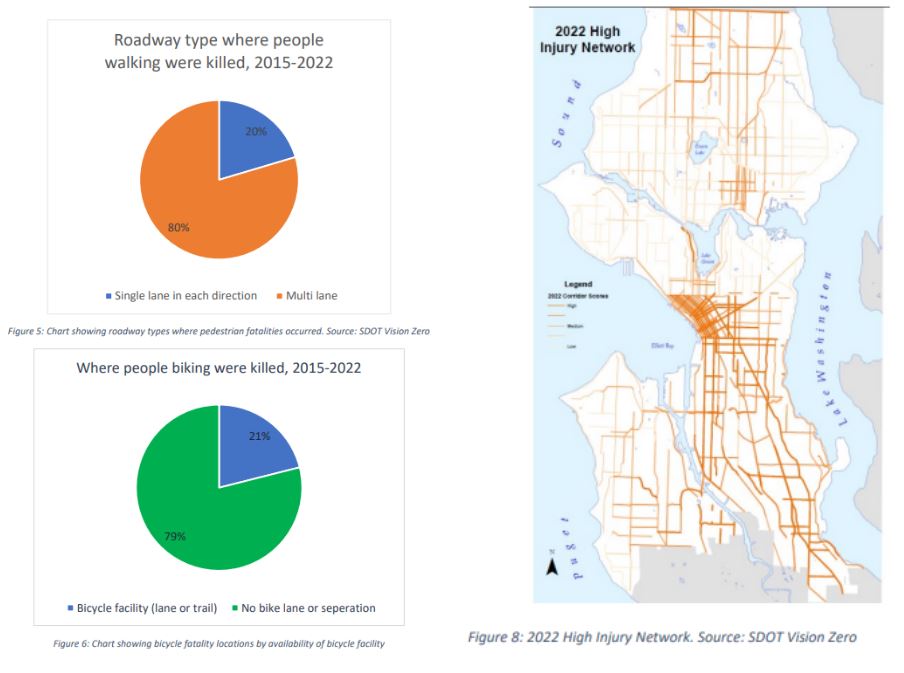

With fewer office commuters and focusing downtown as a residential neighborhood, we should rethink how its streets function. Currently, most of them are one-way, multi-lane roads that operate as a highway on- and off-ramps during peak times. After rush hour their lanes sit empty.

This detriment is by design. Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) designates over 60% of downtown streets as arterials, proving the core is not designed for those who live there, only for those who want to get out of there. We even have digital signs alerting impatient drivers how many minutes they have before they’re on their way out. With the Vision Zero report showing downtown Seattle as a “high crash corridor” something must change, or else Seattle’s dangerous traffic violence will continue to unravel.

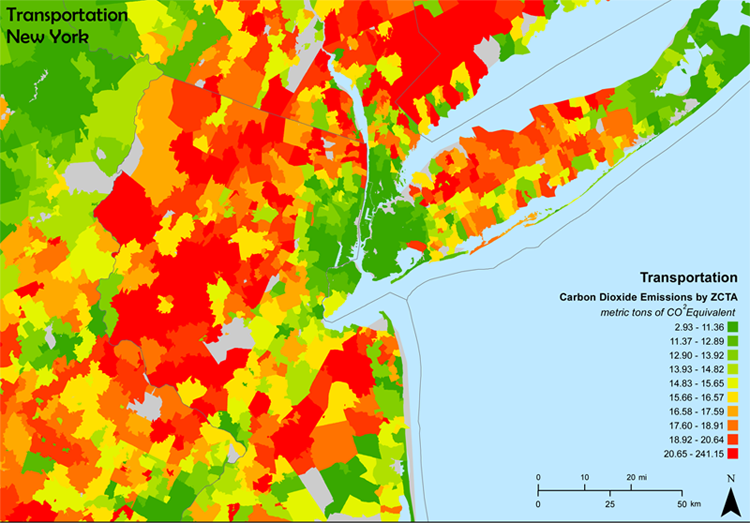

We should convert every street into a bidirectional, two-way street. This slows down cars and offers the opportunity to narrow vehicular space with bus only lanes, streeteries, wider sidewalks and protected bike lanes. We should be investing in space that moves people outside of the car, since most downtown residents and commuters do so without one, and especially since personal vehicles are Seattle’s #1 source for greenhouse gas emissions.

3. Plan Transit that Encourages Ridership

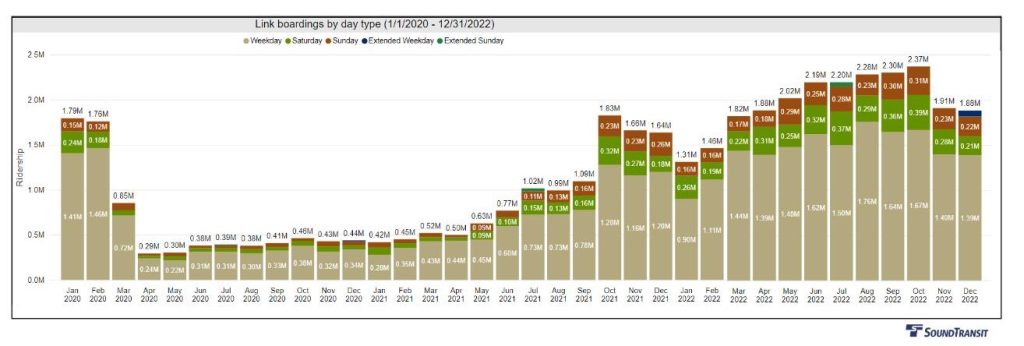

We are amid a transformative investment in light rail. Link ridership has already eclipsed the pre-pandemic levels, with three new stations opening in the north end. With expansion planning underway, downtown’s Westlake Station is about to become the nexus of Seattle transit. We have an opportunity to connect our regional and local transit with interchanges, redevelop publicly owned parcels like the King County Campus, and graduate Seattle from fragmented modes to a truly regional hub for sustainable movement.

We should not be bickering about track sizes. The Streetcar connector needs to be supported, built, and expanded to other neighborhoods. Bus ridership will grow and expand by moving some routes off 3rd to other avenues such as 2nd or 4th. The 3rd Avenue “transit mall” is getting a redesign. Unfortunately, current plans include an option that eliminates some routes from entering the core, forcing riders to transfer to a 3rd Avenue shuttle bus to keep moving. This would be a total travesty and make transit use a bigger pain for riders who will ultimately seek other modes like driving or staying home. Misguided ideas to solve problems while creating others are exactly why we need to be smarter about planning transit in this recovery.

4. Go Beyond Office Conversions

The new hot topic is converting offices to housing. But that will only happen in special cases, cases like a full building conversion on specific buildings with narrower floor plates. (Here’s a great explainer from the New York Times.) All will come at a cost premium. Many offices that will see rising vacancies cannot be converted into housing anyway, but that doesn’t mean they can’t convert into a school, daycare, grocery store, or many other needs for downtown residents.

Downtown also hosts massive parking garages that can be converted into housing and other uses. Plus, we can stick some housing on top of low-rise buildings and continue to build more homes. The possibilities shouldn’t be limited to just empty offices, nor should the conversion strategies be limited to just housing. For downtown to flourish, we need all the space we can get to deliver the needs to make our core vibrant.

5. End Regulatory Hurdles

As the downtown core looks to encourage all solutions to revitalize, we need to suspend regulatory hurdles that slow us down with self-inflicted process. All of downtown should be exempt from community review. One condo has used these programs and design guidelines to hold up 3,000 homes and $40 million in affordable housing payments by filing delays with relative ease. Suspending these burdensome regulations will speed up delivery. Other moratoriums on regulatory behaviors should include a suspension of all building modulations, setbacks, tower separations and floor area limitations.

We need to elevate the right to build homes within people’s property. With the land use code’s restrictions hindering the sustainability and, frankly, the attractiveness of buildings, suspending these will encourage developments we can be proud of as we move forward.

6. Mix Up a Variety of Uses

We don’t need a “Central Business District” a “Retail Core” and an “Entertainment District”. Planners think the city is a TV dinner and that we need to separate the peas from touching the potatoes. But cities are more like a salad, and we need to mix it all up in a giant bowl.

This ensures each bite captures all the flavors which is what makes for a great city and a great salad. Good cities and good salads are healthy. Places like Paris and Barcelona are recovering, and that’s because they don’t quarter off the city for different types of activities that live and die depending on the time of day. Their city is mixed up, with uses everywhere, all connected on foot or by tram.

7. Encourage Families to Live Downtown

Cities thrive when they have children in them. There needs to be an elementary school downtown. Junior high and high schools need to be a short walk or transit ride away. Right now, there are no public schools downtown. Downtown’s under-18 population (which is nearly 6,000 currently) is forced to leave the core to go to school. We also need more childcare, and affordable childcare downtown. There needs to be family sized apartments, large enough to encourage people to live in the core, and we need affordable family homes as well.

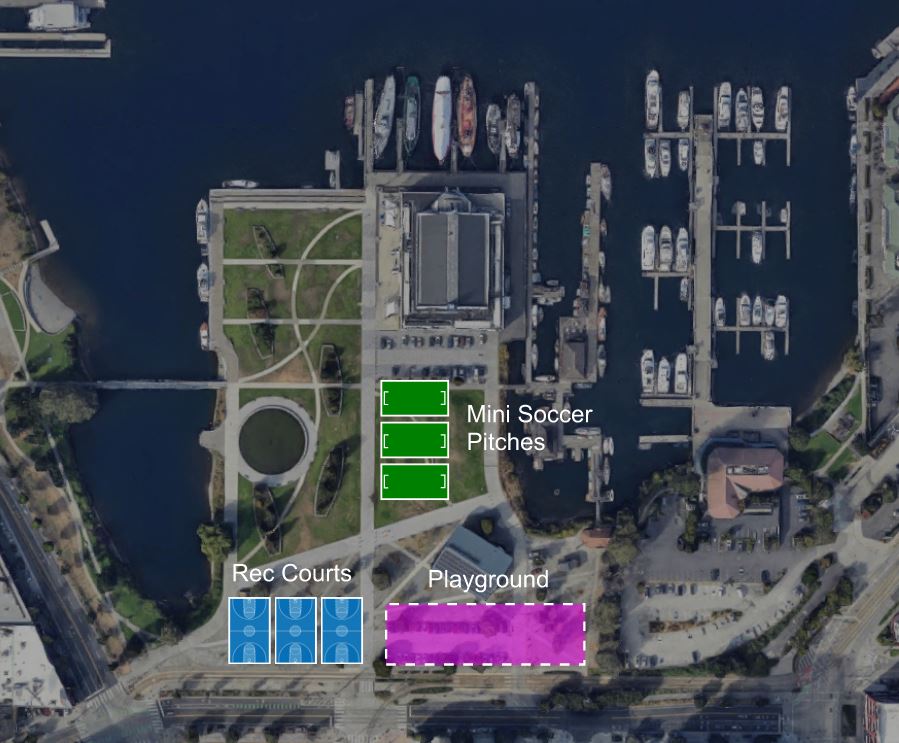

And these kids need somewhere to play. Downtown needs to build more playgrounds for children. Lake Union Park could have more vibrancy if we placed sport courts and playground in the expansive spaces which sit virtually empty most of the time.

8. Create Pedestrianized Spaces

For decades, people have been asking for Pike Place Market to be pedestrian only during operational hours. Now is the time to do it. The people driving in the market always realize it was a mistake, and we waste so much space having vendors park their cars up and down these two blocks. The vendors already have spaces in the garage. Get rid of the cars during business hours and fill this space with outdoor dining.

Further north, close off Pine Street between 4th and 5th Avenues and re-connect Westlake Plaza as it once was. In the 1990’s revitalization of downtown, we bisected the City’s one public plaza by allowing cars to drive through it. It’s way past time to return this space to people.

Going further, every single one of downtown’s neighborhoods needs a multi-block, fully pedestrianized street. Start with Westlake Avenue. Close most of it off, turn it to a park, and let the streetcar go through it. Every single neighborhood in our city deserves a pedestrian-only street with commerce and housing, and we should kick off this program with downtown.

A Recovery that is Sustainable and Protects our Public Investments

Condensing life and opportunity to the core is nothing new, it’s how things used to be. So, let’s get back there. Reduced emissions of urban living shouldn’t be short changed either. The 8.8 million people who live in New York City produce half the emissions of our entire state’s population (which has a million fewer people). So, the downtown recovery is not only about restoring commerce, tax bases, and vibrancy. It’s about reaching our sustainability goals as a city.

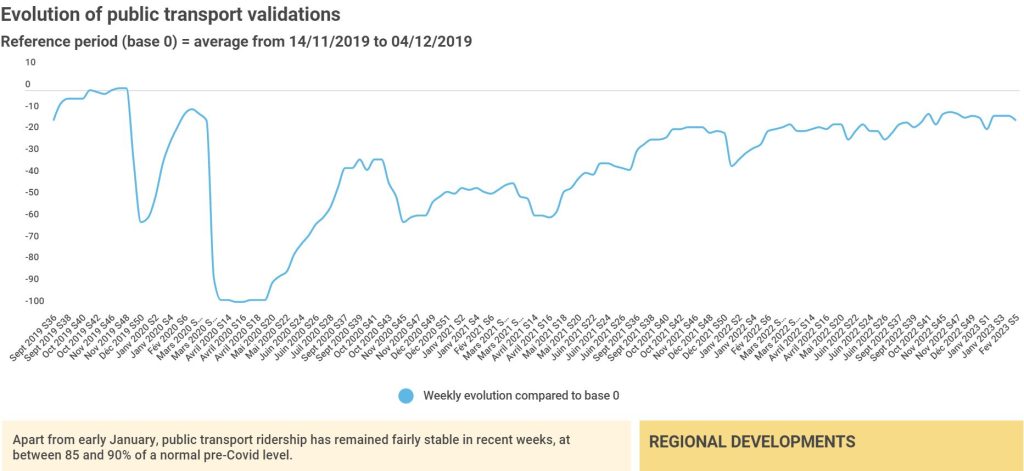

A diverse recovery is also about protecting our investments. We have invested a lot of public money into a transportation system that is suffering from lost revenue and low ridership. That’s largely because we put all the eggs into the single basket of office commuting and never hedged our bets. New York City’s Subway is similarly seeing ridership plummet, designing itself as an office commuter peak load system. Paris is not. That’s because Paris offers transit to connect to a variety of neighborhoods and never designed itself around office commuters. It’s time to rethink Downtown Seattle, to diversify our portfolio and protect our investments.

A Defined Recovery

Seattle’s recovery plan needs less vibes and more targets. Build 10,000 homes, two schools, ten playgrounds, two pedestrianized streets and ten new protected bike lanes in ten years. Call it the 10,000/2/10/2/10 in 10 Plan. Okay maybe we need to work on the slogan. The bottom line is we can’t just say we want downtown to thrive without quantifying it.

These are the things that make a recovery worthwhile on paper. In addition to protecting assets and balancing a budget, Seattle must encourage the kind of social vibrancy we want to see from a city. A city of housing, affordability, and a mixture of people and uses in a safe, prosperous environment. We say we want a downtown recovery, but getting it done requires real, attainable goals. These kinds of direct, visible strategies will help us achieve the mission. And when this is all done, I bet the office workers will want to come downtown and be part of it.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.