Officials say they’re embracing housing growth, but have some caveats.

As Washington’s middle housing bill, HB 1110, advanced through the legislature during the first few months of 2023, few city governments were pushing back as ardently at every stage of the process more than Woodinville. The city of 13,000 people on the northern edge of King County, famous for its wineries, was one of the most high-profile opponents of the bill, along with cities like Mercer Island, Edmonds, and Spokane Valley.

The city’s desire to stop the bill was so intense that one regularly scheduled city council meeting in late February council was sent into recess so that Woodinville Mayor Mike Millman and City Manager Brandon Buchanan could testify against HB 1110 in the House appropriations committee. At those city council meetings, there was near unanimity that Woodinville should be pushing as hard as it could to stop the bill, with one councilmember, Rachel Best-Campbell, even going so far as to suggest that Representative Davina Duerr, elected by the 1st Legislative District which includes the city, was not adequately representing Woodinville because she is a sponsor of the bill.

But Millman, a former station captain with the Everett Fire Department running for reelection this year, wanted to set the record straight regarding why Woodinville’s city government opposed HB 1110. Officials in Woodinville see the city as unique, with a special set of concerns that stem from the way that the city is trying to concentrate growth in a dense downtown with tourist-attracting businesses. The city also has limited transit access, especially outside of the downtown core.

On a mid-May afternoon, I met Mayor Millman, along with an assistant to Woodinville’s city manager, at city hall for a tour of the projects that Woodinville is focusing on. Millman himself lives downtown, and not in the single-family neighborhoods that he was advocating be left alone during the legislative session. We piled into his Telsa for a whirlwind tour of Woodinville’s picturesque and growing center and its sprawling periphery.

City leaders expect Woodinville’s population to grow about 40% within the next five years, with most of that growth concentrated around downtown, where upscale restaurants and bars are flourishing. In other words, the city of just over 13,000 would add more more than 5,000 residents if those projections come true, even as most outer neighborhoods remain largely untouched.

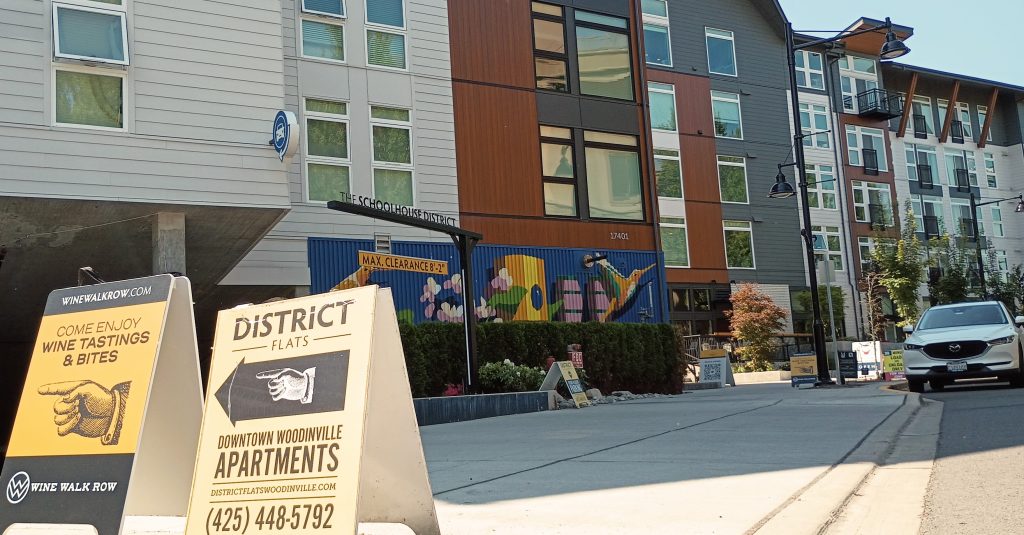

Molbak’s Garden Store, a 20-acre retail storefront in the middle of downtown Woodinville, is being transformed into a 1,400-unit residential complex with retail and open space. The nearby Woodin Creek Village development, heading toward its fifth phase, is adding 791 homes. And the 4.25-acre Woodgate Shopping Center is being replaced with 207 units, including 21 dedicated as affordable homes. These are the types of transformations that other cities would do anything to see happen in their downtowns.

This isn’t to say that Woodinville is incorporating best practices everywhere it can. The city is poised to adopt more stringent off-street parking requirements, and is currently in the process of widening State Route 202 through the middle of downtown from four to eight lanes. Woodinville is locked into an auto-oriented development pattern, to some extent, unless King County and Sound Transit leaders prioritize increasing transit to the city. Currently, Sound Transit’s express Route 522 bus extends to Woodinville from Bothell, but not on every single trip. Thirty minutes between trips is common during peak hours. But that could change once the system is more built-out.

Neither Sound Transit’s I-405 bus rapid transit project nor East Link light rail are ever planned to reach Woodinville despite the significant efforts the city is making to increase housing density in downtown. Millman would like to see the Woodinville Park-and-Ride, which sees less use now in the work-from-home era, redeveloped into an affordable housing complex with commuter parking available underground. But nearly all of these decisions are outside the city’s direct control, with the ownership of the park-and-ride in King County’s hands.

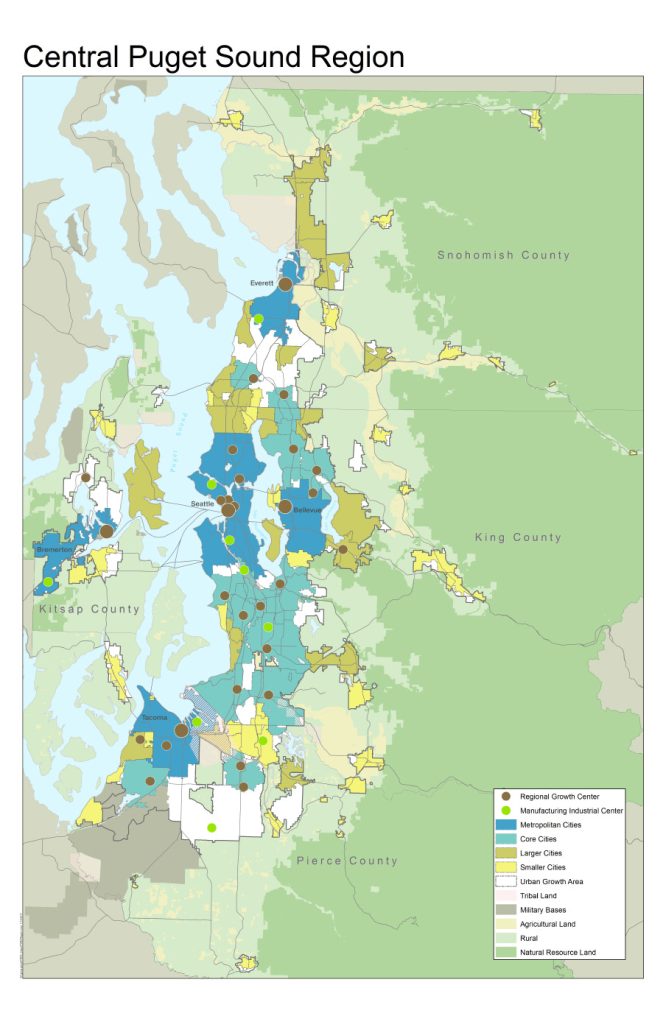

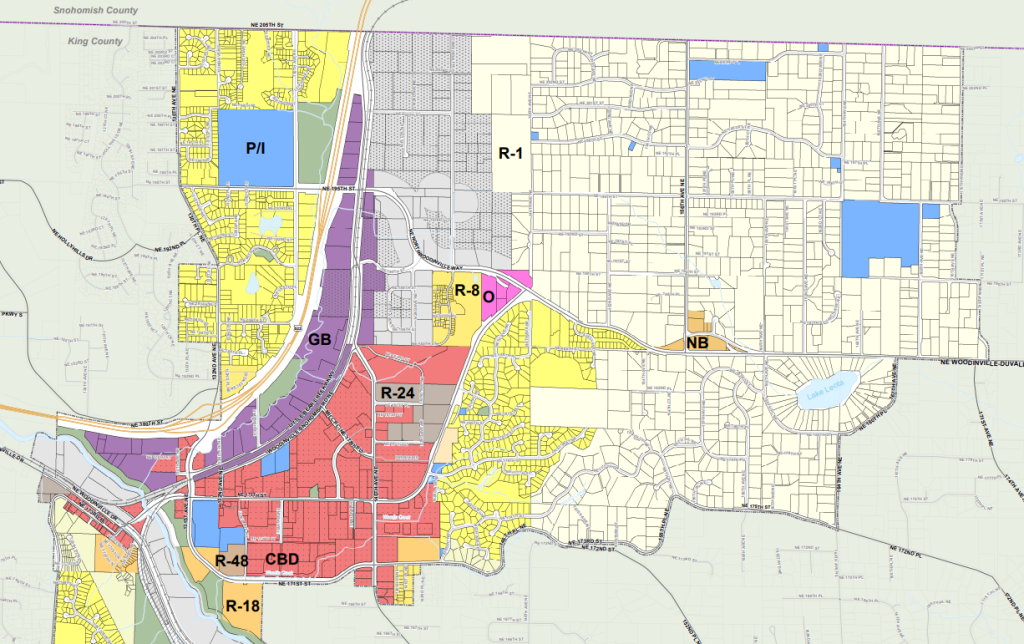

Millman drove me out to the fringes of the city where R-1 single family zoning dominates and the focus of the city’s concerns around the state raising the level of minimum density allowed on residential lots to four units, as in the original version of HB 1110. Woodinville is on the edge of the growth boundary established in the 1990’s by the Growth Management Act (GMA), which also set growth targets that cities within the boundary had to meet or face (mild) consequences.

“Getting sewer lines out to this neighborhood…it would have really knocked us off all of the stuff that I’m showing you, where we’re concentrating our growth, where we’re blowing away our GMA targets, doing our affordable housing, and making the city very walkable, sustainable, vibrant,” Millman said.

On the septic system issue, Millman once again pointed to Woodinville’s uniqueness.

“I suspect there is nothing like our R-1 between here and Seattle… I would be shocked if there was an area the size of our R-1 on septic between here and Seattle,” he said. “For us, it’s an either-or thing. We could develop out there, but because of staffing levels and costs, everything else would stop. Some of it would stop mid-stream, which would be real problematic for us,” he said. “It’s not aligned with our strategic vision at all.”

“That is the biggest crux of the problem… we’re going to take what we’ve been doing downtown, and divert staff money, time, and resources to try to get sewer out here, with cooperation from the Woodinville water district,” Millman said, pointing at the broad expanse of 1970s tract homes that make up the R-1 zone. “Or will we continue what we’ve begun which is building out our downtown, and the density near our park-and-ride, near services… make it walkable near Eastrail.” Now that HB 1110 simply requires the city to allow two units per lot, Woodinville doesn’t have a problem with it, since accessory dwelling units (ADUs) were already allowed in those R-1 zones.

I asked Millman what he says to state lawmakers who argued that the time had come to raise the floor of Washington’s base residential density.

“I agree with them,” he said. “We have a housing shortage, we have a housing stock problem, and it overlaps with homelessness and affordability.” Millman noted that he’d been able to buy a relatively affordable condo in Woodinville several decades ago, and be able to upgrade to different types of housing before ultimately purchasing a house in the city. He sees that as very tough for his two sons, age 23 and 21. “That path seems to be a problem now. I don’t know how somebody that age is going to get into that housing, the way it exists right now.”

Millman wants to see condo liability laws relaxed so that more of the dense apartments being built in places like downtown Woodinville are instead ownership opportunities for people. But he is glad to tout the work that Woodinville is doing around adding affordability, since he was elected to the Woodinville City Council in 2021. “We’re starting from a very low bar, having no affordable housing since the ’80s, to having 140 plus [units] in just the last six months,” he said.

The Puget Sound Regional Council’s analysis of HB 1110 suggests a conservative impact of the bill over the next 20 years to be an additional 75,000 to 150,000 units of housing across the region. I asked Millman how he would have felt if, thanks in part to Woodinville’s pushback, the bill would have failed this year. He didn’t directly answer, but did connect a failure to move quickly on housing affordability to the increase of homelessness in places like Everett.

“We need more affordable housing,” Millman said. “We need housing stock at multiple levels. I applaud that. I want future generations to enjoy our area as much as others have from different generations.”

“We’re picking up the pace, on Woodinville’s side, as quickly as we possibly can, with fiscal and staffing restraints,” he continued. “I support all of the intent of 1110 and all of the stuff that is going on, because we need it. And we’re working as hard as we can to actually meet those goals and do as many affordable housing units as we can practically do.”

With the state of Washington taking an increasing interest in how much housing local cities are producing, it remains to be seen whether Woodinville will once again butt heads with the state legislature over how best to create those new units, even if they seem to have the same end goals in mind.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.