Plummeting permits could point to a housing slowdown and less affordable housing money after a banner year.

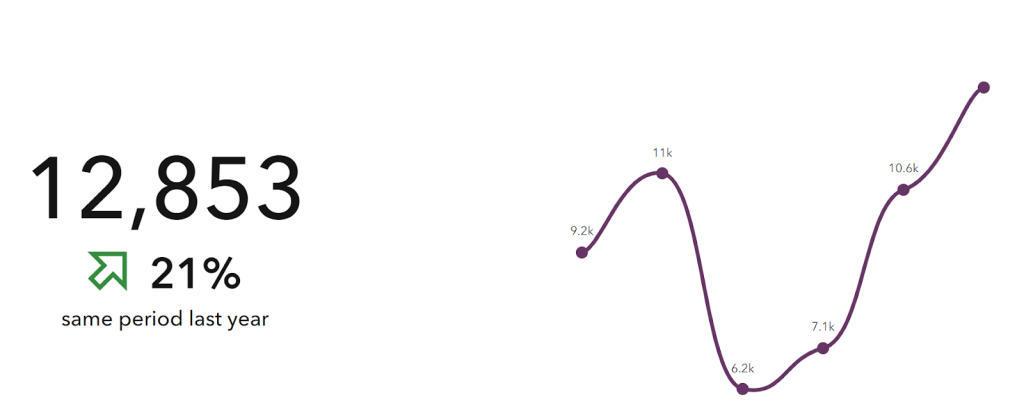

Seattle’s housing production set a new record in 2023, producing 12,853 new homes, according to data from the City of Seattle. This is the most homes built since at least 2005, the furthest back we have recent records, and a 21% increase over 2022.

This appears to be excellent news given the strong headwinds — inflation, interest hikes, supply chain challenges, labor shortages — pushing back on housing construction. It’s also notable because 2023 is likely the first year that all completed units were permitted after Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) law took effect, following its passage in 2019 and a rush for developers to apply for permits before the new fees took effect.

However, there are still concerning trends. During the summer of 2021 a regional trade group, the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties (MBAKS), suggested a dire future for townhomes in Seattle. MBAKS identified MHA as a primary culprit: “Unfortunately, MHA fees are severely limiting new townhomes — a lower-cost, family-sized homeownership option. Post-MHA, townhome permit intake has dropped by nearly 70%.”

2021 went on to set a record for townhome production but staff in Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office continued to raise concerns about permit applications. Those concerns appear to have been somewhat justified, if not as dire as initial concerns suggested. Townhome completions declined in 2022 and 2023, though they’re still above pre-MHA totals.

With overall housing production up after the MHA rezones were passed, it’s less clear what caused a decline in townhome production. It’s possible MHA is simply suppressing production. Other factors could be external headwinds pushing developers toward other projects, or Seattle’s 2019 accessory dwelling unit (ADU) legislation. ADU production is way up and some builders have indicated they’ve shifted from townhomes to accessory units. This is concerning for two reasons. First, the city’s regulations, like uneven MHA application, may be pushing developers into housing types that are worse for renters and owners. Second, many accessory units don’t contribute MHA dollars.

Despite the overall good news on production, permit applications are very concerning. Since the 2020 peak, the number of permit applications has fallen a dramatic 71%. This drop is close to the decline we saw with townhome permit applications in 2021 and that drop was followed by two consecutive years of declining completions.

These promising production numbers coincide with research from the Furman Center reinforcing these observations. The researchers found that MHA did not reduce the overall housing supply in Seattle but they did find developers choosing to build away from MHA zones. “We find that there is no overall supply decline, but strong strategic substitution of new construction away from blocks and parcels subject to the MHA,” their report states.

2024 is shaping up to be an important year for housing in Seattle. The City will release its comprehensive plan and the state legislature is likely to consider more housing bills. These policy debates are taking place within the context of record housing production and plummeting permit applications. And the most important metric is prices. Both Seattle rents and sale prices appear to have decreased in real dollars, accounting for inflation, after the passage of MHA.

It’s nearly impossible to prove a counterfactual but it’s increasingly persuasive that Seattle’s MHA law — upzoning with affordability contributions — has been a success. It looks like the law contributed hundreds of millions to affordable housing while possibly increasing the number of market rate homes and consequently reducing prices. Still housing costs continue to be a burden for many people. If private development continues to drop, that will reduce the money for affordable housing. More private market development will create more affordable housing dollars while simultaneously reducing market-rate rents and demand for subsidized housing. And while prices may have fallen, planners and policymakers need to push prices even lower while considering how regulations impact the housing typologies people need.

MBAKS put together some requests for implementing last year’s missing middle legislation, House Bill 1110. Allison Butcher, a senior policy analyst at MBAKS, said that “the biggest priority for us locally and looking at the state is successful implementation of this law.” MBAKS member and developer Cameron McKinnon said he’d “like to see a focus on opening up middle housing to a wider area,” specifically indicating they’d like to see unit lot subdivision allowed widely across the city. There seems to be broad support for the general principle of allowing homes on smaller lots. On the first day of the legislative session, the Washington House re-passed a lot-splitting bill they passed in 2023, sending it back to the Senate, indicating an urgency to make it happen.

It remains to be seen if Seattle will show any ambition to expand housing with its comprehensive plan or do the absolute minimum. Or worse, illegally dodge state mandates. Since passage of the MHA law, Seattle’s done little to expand housing options. Most efforts have been tinkering around the margins, like the ADU legislation, upzoning a few blocks in the Downtown retail core and allowing housing in some limited industrial areas. Meanwhile, apartments are still illegal in most of Seattle’s residential zones.

Grassroots efforts pushed the City to legalize apartments citywide, but Seattle’s executive branch proposed much more modest changes. Then later, the Harrell administration delayed the plan’s release multiple times, eventually pushing it out past the fall election and avoided making it an campaign issue. Harrell’s earlier idea, floating reforms to encourage microhousing in existing apartment zones, has yet to go anywhere, and, like other stalled reforms in Seattle, inaction is leading the state legislature to consider superseding this local decision.

Even if Seattle meets minimum compliance with the state law it could continue prohibiting apartments in many neighborhoods. Today Seattle’s planners still have a wide range of power to shape their comprehensive plan. However, it seems apparent now that the city’s failure to seriously tackle its housing crisis is forcing the the state legislature to act, ultimately removing Seattle’s power to continue slow-walking changes.

Owen Pickford

Owen is a solutions engineer for a software company. He has an amateur interest in urban policy, focusing on housing. His primary mode is a bicycle but isn't ashamed of riding down the hill and taking the bus back up. Feel free to tweet at him: @pickovven.