Despite skyrocketing housing prices across Washington State, the state legislature has failed to pass any bills easing statewide housing restrictions and promoting missing middle housing housing growth in sacrosanct single-family zones. Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell had concerns with the missing middle bill and declined to endorse it, but he is now floating an idea that could ease the shortage of affordable housing: micro-apartments.

Harrell broached this policy idea in a recent interview with the Puget Sound Business Journal.

“I will commit to examining the council’s decision around micro-apartments, then take that information into broader consideration when reviewing all housing solutions as part of my administration’s efforts to build more housing and density to address the housing affordability crisis,” Harrell said.

While Harrell stopped short of promising policy changes, re-opening the decision presents an opportunity for improvements at least.

Harrell was on the city council when the legislative body unanimously voted to ratchet up restrictions on micro-housing in 2014, responding to a micro-apartment building boom that was stirring a neighborhood backlash. Micro-apartments — many branded as “aPodments” — were popping up in neighborhoods across the city, and neighbors bristled at what they perceived as shoddy design, the lack of opportunity to voice their complaints at design review meetings, and concerns over impacts on street parking.

The micro-housing boom in the early 2010’s had been driven by these projects’ ability to skip design review, take advantage of the Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE), and fit significantly more units into the same building footprint. The projects also benefited from parking reform that waived off-street parking requirements in the city’s designated Urban Centers and Urban Villages, which constituted a major expense for builders. The combinations of these idiosyncrasies in Seattle’s byzantine land use regulations made micro-apartments profitable to build and easy to permit, for a while.

The city council’s 2014 reform paired with more restrictive rules made by the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) largely killed this business model. However, more than 4,000 units were already in the development pipeline vested under previous rules, said then-Councilmember Tom Rasmussen, a major critic of micro-apartments.

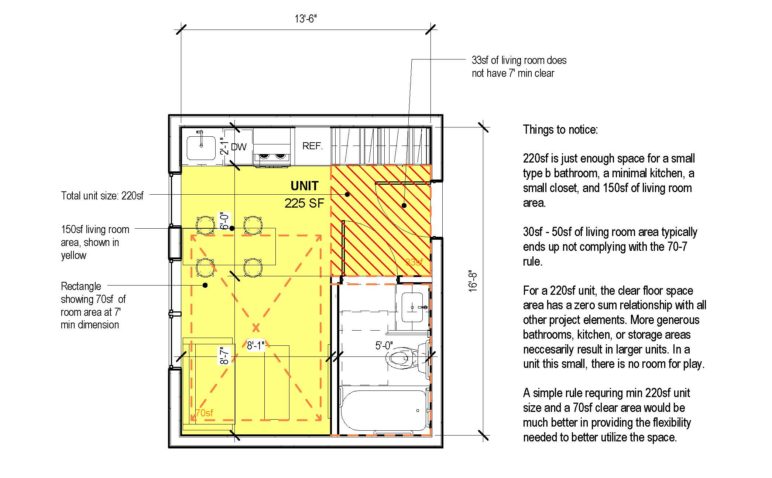

The new legislation established “small efficiency dwelling units” (SEDUs) of at least 220 square feet per unit as the smallest housing form permissible and required at least two sinks each. Previously, congregate micro-apartments averaging as little as 140 square feet had been permitted, although buildings did provide communal living space and community kitchens to supplement. The city council also raised MFTE requirements from 20% to 25% of units unless family-sized units were provided, which SEDUs projects obviously don’t, and required deeper affordability for micro-apartments to qualify. SDCI, meanwhile, set a Director’s Rule that required seven foot wide hallways, 70 feet of clear space, and 150-square-foot living rooms, and this made the actual minimum buildable size of the new SEDUs larger still, builders reported.

As a result, David Neiman of Neiman Taber Architects, whose projects have included micro-apartments in the past, declared microhousing dead in a 2016 post in Sightline Institute. The new rules pushed the average SEDU size to 280 square feet per unit, Neiman wrote at the time, and added upwards of $400 to their expected rent. The congregate style 175-square-foot units rented for $900, but the larger SEDUs under the new rules would need to charge about $1300 to cover their costs, he said. While SEDU projects could still still “pencil out” as feasible to build, they now served a different housing market — more middle-income housing than an option for low-income service workers and students.

Reached by email, Neiman said he will be meeting with the Harrell administration later this month to discuss reforms, but he didn’t yet know what the Mayor’s plan entailed.

“I am really heartened and excited by the news,” Neiman said. “My office is busier than we have ever been, but none of our current projects are SEDUs or congregate housing,” he added.

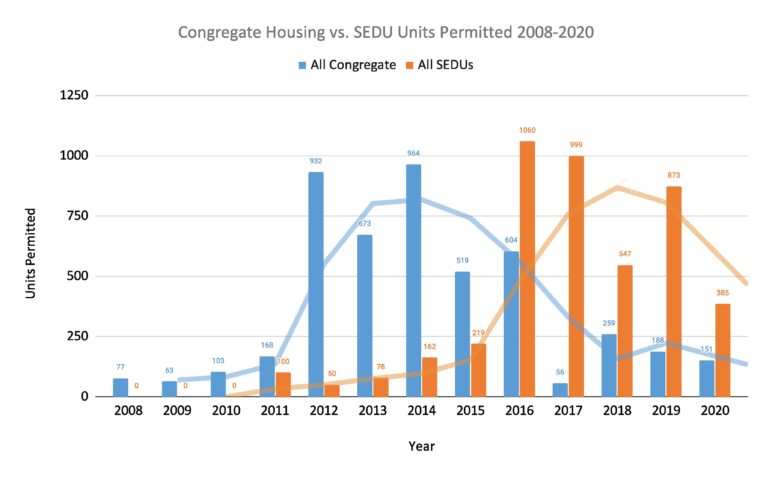

Neiman published an update in 2021 and his analysis of permitting data showed the micro-apartment pipeline didn’t dry up completely, but has tapered off — even in a period of high demand and climbing rents. Congregate unit permits are way down, and SEDU permits haven’t fully picked up the slack.

Micro-apartment permits have also been slower in coming with the new design review requirements — lengthy design review and permitting times is a problem afflicting many housing proposals in Seattle. The surge of permits ahead of the 2014 reforms did sustain the micro-housing pipeline for a few years after the tighter restrictions were enacted. Congregate unit production actually peaked in 2016 with 638 units delivered, slightly above the previous 2014 high-water mark, according to Neiman’s figures. However, by 2018, small efficiency production surpassed congregate housing production, which had cratered to the mid-200s. From 2015 to 2020, Seattle added 2,041 small efficiency dwelling units, according to those same figures.

Neighborhood opposition persisted even with the higher standards and the new design review requirements. In fact, some used the design approval process to try to kill projects rather than improve then. For example, neighbors rallied against a Fremont small efficiency project (designed by Neiman Taber Architects, incidentally) and even branded it “steerage” housing in an angry Seattle Times op-ed.

Many of the same arguments used against congregate housing were used against small efficiencies, as if the raised standards had gone unnoticed by homeowner activist groups opposed to apartments near them. And ironically, some of the same groups opposed Mandatory Housing Affordability rezones because they said they were worried historic apartment buildings largely composed of studios like The Malloy in the University District would get demolished, destroying “naturally occurring affordable units,” they said. Some of those studios were about the same size as the new small efficiencies they often opposed building.

Despite that history, the Mayor appeared optimistic he could overcome neighborhood opposition to win support for a greater role for micro-housing. “The anti-density single-family bloc is a potent force in city politics, but Harrell said he doesn’t fear it,” PSBJ’s Marc Stiles wrote.

“My administration will be known for listening and, again, making data-based decisions, and if the data of warrants increased density in certain neighborhoods where it makes sense and we work with communities and listen to them, then those will be the decisions we we make,” Harrell told Stiles.

While apodments, as the poster child of the congregate housing boom, had been vilified as substandard housing back in 2014, Mayor Harrell pointed to them as a promising option.

“I think all things like (micro-units) that should be back on the table to evaluate,” Harrell said. “My administration will look at apodments to see what adjustments could be made and if they can once again become an effective tool to achieve density.”

Harrell has yet to lay out a timeline for micro-housing reform and it’s not yet clear how much weight his administration will throw behind the initiative. Harrell’s chief operations officer, Marco Lowe, came over from the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish counties (MBAKS), which has advocated for easing restrictions. As a small developer, Lowe has some experience building apartments and small efficiencies himself. It could be he’s asked to lead on this policy, but Lowe couldn’t confirm that yet.

“With regard to micro-apartments, the mayor has shared that he would like to specifically examine the Council’s 2014 decision around micro-apartments,” Harrell spokesperson Jamie Housen said. “From there, he will bring that review into broader consideration when considering a full spectrum of housing solutions as part of the administration’s efforts to build more housing and density to address the housing affordability crisis. This is in early stages, so I cannot speak to timeline or process.”

Neiman shared some thoughts on what changes he is advocating for to help micro-housing make a comeback in Seattle. He emphasized the importance of allowing market-rate congregate housing in urban villages and urban centers where multi-family housing is currently allowed, repealing administrative and zoning regulations that increase unit size, which increases production costs, and adjusting required MFTE contributions for micro-housing projects so that it “isn’t hostile to micro-housing development.” Neiman also signaled out “a few obscure but significant regulations that regulate the amount of bicycle parking and the amount of space given over to in-building waste rooms for garbage collection” as being significant cost drivers and impediments.

Additionally, Neiman floated the idea of encouraging public-private partnerships to create deeply affordable micro-housing to serve vulnerable populations, such as people exiting homelessness.

…we could allow allow non-profits to use housing levy and MHA funds to purchase or master lease congregate housing produced by the private market. Nonprofits have to navigate a maze of regulatory burdens that make it difficult for them to produce housing efficiently. By the same token, private companies lack the expertise and the mission focus needed to house and serve vulnerable populations.

Public-private partnerships, with private developers producing the housing and non-profit organizations operating them and delivering the associated social services, could leverage the best of both worlds and get help to the most people.

David Neiman

Nonprofit housing builders don’t face the same strict regulations when it comes to building microhousing, he added, arguing that policies should be put in place to encourage nonprofits to build microhousing, especially in the context of the homelessness crisis.

“The prohibitions on microhousing that apply to market-rate developers have never applied to housing nonprofits,” Neiman said. “But these nonprofits have not chosen to build dense microhousing, opting instead to build conventional apartments even for transitional housing for people coming straight off the streets.”

While The Urbanist supports micro-housing, it’s not a solution that gets at the lack of family-sized housing in Seattle, which would leave a big part of the housing affordability crisis unresolved even if micro-housing reforms are successful. Still, it’s an important piece of the puzzle with some unique advantages. Living in a small efficiency or congregate housing is one of the most environmentally sustainable ways to live since it takes less energy to heat and cool and fewer materials to build and furnish. It also allows people to live in high-demand, transit-rich neighborhoods where they’d otherwise struggle to afford housing costs. Congregate housing or cohousing also has sociological benefits when done well and can combat social isolation. Plus, as Neiman emphasized, it’s simply cheaper to build, which stretches housing investments farther.

That said, the City needs to move ahead with a broad package of bold interventions, not just micro-housing. Statewide missing middle housing reform would have made a nice addition to that policy suite if only the State Legislature, with more support from hesitant local leaders like Harrell, had passed it this year. Greatly boosting funding to add social housing also appears key to resolving the housing crisis given how many people the market is leaving behind.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.