The Seattle City Council voted to approve a new contract with the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) on Tuesday with a 6-3 vote, signaling less unity amongst councilmembers than is typical in Seattle for police contracts.

Councilmembers Alexis Mercedes Rinck, Eddie Lin, and Rob Saka voted against the new SPOG contract, citing lack of progress on key police accountability issues. Rinck flagged continued obstacles to deploying civilian crisis responders.

“The badge earns trust not from its shine, but from the conduct behind it,” Saka said. “The proposed SPOG CBA (collective bargaining agreement) is a bad deal for the City of Seattle. Accountability provisions contained in that contract are too lightweight and do not at all close the gap between what’s set forth and our accountability ordinance, our city values, and the terms and conditions and the final agreed upon contracts. For those reasons, I will be opposing and voting against this deal.”

Both Saka and Lin referenced personal past experiences with police brutality.

“It’s important to recognize that the grief and the anger and the frustration that led to the nationwide protests in 2020, those are just as real today as they were then,” Lin said. “We have never addressed the root causes, the generational trauma that was inflicted upon our communities. It continues to be inflicted upon too many. And you know, we can’t just sweep it under the rug. We can’t just ignore it or move past it, although many people would like to, because it is a festering wound that will continue to impact our communities, continue to impact our ability to provide true public safety.”

Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth voted in favor of the contract, in spite of saying on the campaign trail in 2023 that she would oppose a SPOG contract that didn’t grant subpoena power to the Office of Police Accountability (OPA) and the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) and didn’t remove limitations on how many OPA investigators are allowed to be civilian versus sworn. The new SPOG contract doesn’t achieve either of these goals.

Councilmembers voted unanimously in favor of the less contentious Seattle Police Management Association’s (SPMA) new contract. Both police guild contracts cover the term from 2024 to the end of 2027. SPOG represents the rank-and-file of the Seattle Police Department (SPD), while SPMA represents SPD’s lieutenants and captains, a much smaller number of employees.

The mayor’s office takes the lead role in negotiating the contract with SPOG leaders, but the City’s Labor Relations Policy Committee (LRPC) plays a key role in the bargaining process, and consists of five city councilmembers. By design, this composes a majority when it comes time for the council to vote on the contract. Should any of those five councilmembers vote against a contract approved by the LRPC, SPOG could choose to file an unfair labor practice, saying the City didn’t bargain in good faith.

However, some police accountability and civilian alternative response advocates, tired of waiting for reform that continues to be kicked down the road, believe such an action would be worth the legal risk. Beyond the lack of accountability wins, critics contend the contract’s generous terms will strain the City budget and siphon resources from other programs that contribute to safety and wellbeing.

The SPOG contract raises the starting base salary of an SPD officer to $118,000, with a pay bump to $126,000 after six months. This base doesn’t include overtime, special event bonuses, or the newly negotiated premiums for language fluency and education.

The negotiated raises, bonuses, and special incentive pay are not tied to accountability standards. Officers with a colorful misconduct record – or, in the case of backpay, even officers who have been terminated – will receive the same negotiated benefits.

Council’s central staff estimates that the contract will cost the City an additional $131.7 million during its term. Financial planning reserves will cover the additional costs through 2026, leaving $43.6 million in extra 2027 spending unaccounted for. Any net new officer hires in 2027 would also require SPD’s budget to grow.

Outgoing Mayor Bruce Harrell made the completion of bargaining for this SPOG contract a priority before the end of his first term. Its passage now, however, a few short weeks before he leaves office, means that Mayor-elect Katie Wilson, along with new Councilmember-elect Dionne Foster and City Attorney-elect Erika Evans, won’t have as meaningful a chance to influence police accountability and alternative response, both important issues in Seattle.

Accountability in the contract

Police accountability didn’t used to be included in police guild contracts, which typically cover wages and working conditions. Moving accountability issues to the bargaining table has drastically reduced their transparency to the public; accountability measures are now enshrined in difficult-to-understand legalese in labor contracts and require confidentiality during the bargaining process, meaning the public doesn’t know what’s happening until a full contract is presented and inevitably framed as a fait accompli.

In turn, this shift to bargaining away accountability has contributed to reduced public trust in police departments, as well as local government overall.

Seattle’s landmark accountability ordinance, passed in 2017, was meant to enshrine a basic level of police accountability, a minimum floor that advocates and community groups intended to build upon and improve in subsequent years. While some aspects of the ordinance needed to be bargained with SPMA and SPOG, that bargaining was intended to happen quickly to allow further progress.

However, a new SPOG contract passed in 2018, negotiated by the office of then-Mayor Jenny Durkan, broke that promise and failed to bargain key aspects of the ordinance, which remain unrealized to this day. As a result, the City has been unable to enact basic police accountability measures, and the conversation has remained essentially frozen for the last several years.

This inability to make accountability progress was a major inspiration for the movement seeking to divert police funding to other programs, which caught fire in 2020 protests reacting to the killing of George Floyd at the hands of police. The defund movement unsuccessfully pushed to cut SPD funding by 50% in 2020 — instead SPD funding has grown — outpacing growth rates at most other departments. Seeing the continued power of SPOG to block commonsense accountability measures while SPD responded violently to protests against police brutality highlighted the systemic issues with policing and the failure of earlier reform efforts.

The newly passed SPOG contract continues the status quo, with the accountability ordinance remaining unfulfilled.

A small gain in the contract that allows longer retention of OPA misconduct files regardless of outcome of the investigation is the result of needing to be in compliance with a state law passed in 2021. The clarification of the 180-day investigation clock modifies a system that some experts have recommended against in its entirety. OPA’s civilian investigators may now assist in serious misconduct cases that might end in termination, but they can’t be the sole lead on such a case. These changes are incremental at best.

On the other hand, SPD will now be allowed to deal with “less than serious” misconduct cases in house instead of referring them to the OPA, in a move SPD leadership has been requesting for years. While this change could potentially free the OPA to spend more time on serious cases while building the leadership skills of SPD officers, the implementation of the system will be key. Removing the OPA entirely from the system and relying solely on the OIG for any review, as the contract states, could lead to problems, as in-house discipline still needs to be consistent, timely, and fair.

The City and SPOG will be entering interest arbitration to determine several issues around arbitration used to appeal disciplinary decisions around officer misconduct. That being said, information about the issues being arbitrated provided by Mayor Harrell’s Chief of Staff Andrew Myerberg indicates that while the changes sought by the City would be an improvement, they would still fall short of the 2017 accountability ordinance, which requires disciplinary appeals to go through a public hearing in front of the Public Safety Civil Service Commission (PSCSC).

The interest arbitration process could take several months to complete.

The CARE team

Supporters of the contract have been citing its new provisions for the Community Assisted Response and Engagement (CARE) team that provides alternative civilianized response to behavioral health-related calls that don’t require a police response. The contract makes the CARE team permanent and allows it to expand at will.

The contract also allows the CARE team to be “solo dispatched” directly from 911 without police co-response. However, the contract also imposes so many restrictions on when solo dispatch is possible as to serve as a serious impediment to the team actually being able to do their jobs.

For example, the CARE team is not allowed to go by themselves to help anyone in a private residence or business, a car, or a homeless encampment. They also aren’t allowed to respond alone if there is any chance a crime has taken place such as public drug use or possession or if expected drug paraphernalia is present, which includes aluminum foil.

All these restrictions prevent the independence of Seattle’s 911 dispatch to determine which responder should go to which calls. CARE Chief Amy Barden has repeatedly explained that dispatch independence is required to make 911 call response times faster.

Earlier this year, the City championed a bill at the Washington State Legislature, sponsored by Rep. Shaun Scott (D-43, Seattle) that would have provided the right for the City to establish an alternative response team that wouldn’t need to be bargained with law enforcement personnel. SPD’s Dan Nelson, who at the time was an assistant chief, testified before the House committee.

“Alternative responses to non-criminal 911 calls is crucial for ensuring that individuals in crisis receive the most appropriate care while allowing law enforcement to focus on serious public safety concerns,” Nelson said at the hearing. “We have proven that the rank and file appreciate the service, and they leverage the service.”

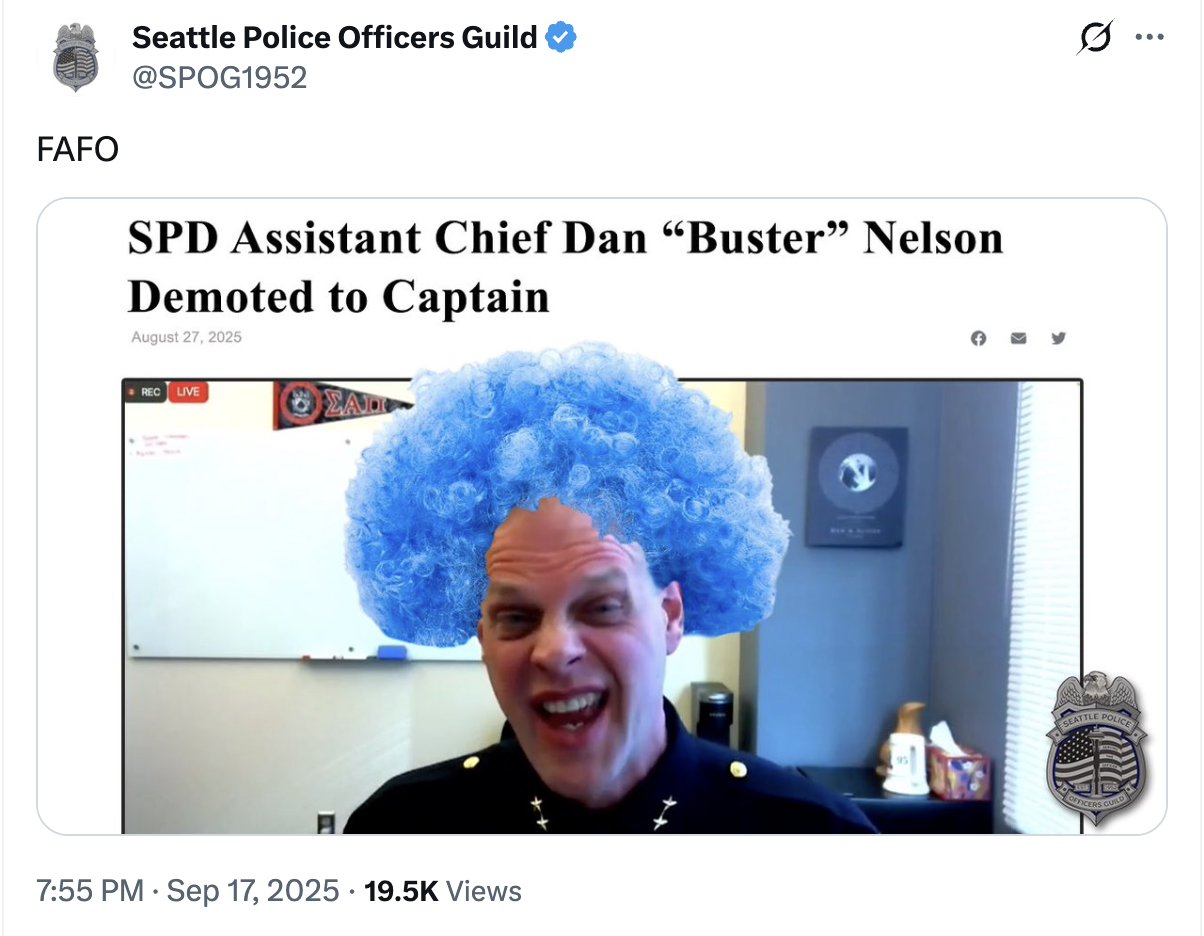

In early March, SPOG’s President Mike Solan released an episode of the police guild’s podcast that featured doctored photos of Mayor Bruce Harrell, Scott, and Nelson dressed in colorful clown wigs, condemning the bill in question.

Several months later, in mid-September, a post on SPOG’s X social media account announced Nelson’s demotion from assistant chief to captain with the caption FAFO (eff around and find out). The post appeared to take credit for Nelson’s demotion as a retaliatory response after he supported the bill that would ensure the smooth operation of alternative response.

Options moving forward

In addition to continuing to push important accountability issues into interest arbitration, many elected officials have highlighted the importance of a state-level fix that would remove police accountability issues from the collective bargaining process entirely.

A bill that would have achieved that goal was introduced in the state legislature in 2021 and again in 2022. However, it faced stiff opposition from organized labor, who worried that even narrowly targeted changes to collective bargaining could represent a slippery slope for labor rights in the state.

“Our system is fundamentally broken,” Saka said. “Our state law keeps it broken. It is past time to address this root cause. Washington’s system is built to produce weak oversight. State law prevents cities like ours from unilaterally strengthening police disciplinary rules. That means anything and everything tied to misconduct must be specifically negotiated, bargained for, and agreed to by both parties. Under current state law, even police misconduct matters are considered routine or standard, quote unquote, terms […] and conditions of employment.”

Saka went on to explain why police misconduct in particular shouldn’t be considered standard or similar to other collective bargaining rights.

“Police officers carry the state’s authority to use deadly force… Nothing about this solemn authority is routine or standard,” Saka said. “This authority to use force and potentially take a life requires a stronger set of oversight, not oversight designed to collapse during negotiations. The legislature must act. The legislature must change this law now so discipline and misconduct rules cannot be bargained away. Without that change, Seattle will continue to face contracts that undermine our values. Lives are literally dependent on it.”

Barring a state law change, another possible recourse is to change the City Charter mandating the existence of SPD so it can be disbanded, as was done in 2012 in Camden, New Jersey. In Camden, the city opted to build a new department from scratch.

During his Seattle City Attorney campaign earlier this year, Rory O’Sullivan suggested something similar: that Seattle move to disband its police department and instead contract its policing services from the King County Sheriff’s Office.

“The point that I was trying to make during the campaign was […] that SPOG has created a whole bunch of roadblocks, and, I believe in a number of instances, hasn’t really negotiated in good faith,” O’Sullivan told The Urbanist. “And so the City should be prepared to keep all options on the table. And one of those options is marshaling a charter initiative to change the charter to allow the City to contract with the county as a bargaining piece to hopefully give the City a better opportunity to hold SPOG accountable.”

Aside from the two larger possibilities outlined above, Wilson will have to get creative in finding ways to move police accountability and alternative response forward during her first term. Since the new contract runs until the end of 2027, SPOG will have the option of stalling and working without a contract for two years in an attempt to avoid having to bargain with Wilson, should she fail to win a second term.

Chief Barden of CARE already has a lot of ideas of how to deploy her team of alternative responders. While she’s hoping SPD will be willing to refer appropriate 911 calls to the CARE team, she’s also setting up arrangements with the King County Jail and local hospitals to be able to receive direct CARE response. The CARE team could also potentially be dispatched through 988, which isn’t a body of work SPOG can attempt to claim.

Plus, the CARE team can continue its proactive patrols in areas where crisis calls are common.

In addition, Wilson can find ways to encourage better accountability directly through SPD and the accountability agencies, focusing on issues that don’t have to be bargained. For example, SPD’s promotion process could be reformed, requiring consultation with a candidate’s supervisor and review of their misconduct record instead of relying solely on test scores. The department’s backgrounding process that resulted in the disastrous hire of former Officer Kevin Dave could potentially be reviewed and changed.

Wilson could encourage more enthusiastic support for the CARE team from current SPD Chief Shon Barnes, whose services she just announced she will be retaining. Wilson will have the opportunity to decide who should serve as the director of the OPA, as the current director Bonnie Glenn only serves until the end of 2026.

In a written interview with The Urbanist last month, Wilson underlined her commitment to transparency, which has often been lacking around issues related to SPD.

“I want people to see a city government that’s transparent about what we’re doing, what’s working, and what challenges we’re facing,” Wilson said. “That’s how we rebuild trust so we can make real progress.”

However, undoing the damage from another SPOG contract that falls short will be an uphill battle, and it could take a long time. Harrell signed the new contract on Thursday, three weeks before his term ends.