The mayor pledged to reveal the Seattle Comprehensive Plan for growth by early March and teased efforts to coordinate growth in South Downtown.

Mayor Bruce Harrell spoke for 45 minutes on Tuesday in his annual “state of the city” speech, but key questions linger about the work ahead for the City of Seattle in 2024. No question looms larger than how to close a gaping budget deficit that is currently estimated around $230 million for 2025 and even more the following year. While Harrell and his allies have yet to offer concrete ideas on where the money to close the budget gap will come from, the mayor did seek to take one option off the table, namely raising taxes.

“The size of this deficit means we will have difficult financial decisions ahead, and, while there are some who would suggest that the answer lies in new revenue, the fact is that passing a new or expanded tax will not address the fundamental issues needed to close this gap in the long run,” Harrell said. “Without changes to how we budget, without changes with how we think about budgeting, this problem will occur again and again and again for the city for years ago delivering a sustainable, balanced budget is a basic responsibility of city government.”

The Mayor largely spent the first two years of his term ignoring the well-known impending deficit, and even sent the city council a 2024 budget that included new ongoing costs for the city to take on, pushing up the expected shortfall up by nearly $50 million annually.

In 2022, the Harrell administration commissioned a “Revenue Stabilization Work Group” inviting progressive, labor, and business leaders to collaborate to seek solutions, but the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce ended up spiking the group’s report, which ranked potential new revenue sources, as it was issued, arguing cuts rather than new revenue was needed.

It was only just weeks ago that Harrell instituted a hiring freeze across all City departments — police and fire excluded — that signs of impending action became visible. Yesterday’s speech was further indication that he has sided with the chamber.

That deficit — and the refusal to raise taxes — makes all of the mayor’s work harder, limiting the opportunity for new initiatives. While Harrell sought to strike a confident tone, the speech largely repackaged old efforts rather than unveiling new initiatives of great significance and imminent delivery.

South Downtown development push

One possible exception was the pledge of “very coordinated targeted growth strategy” for South Downtown. Harrell described the scope of this project as “south of Columbia, north of Holgate, east to Little Saigon, west to Pier 48,” which spans Pioneer Square, Chinatown, northern SoDo, and the massive freeway interchange of I-90 and I-5 (therein lies the rub for creating a healthy, high quality residential neighborhood in the vicinity). The mayor pledged to forge a “new kind of neighborhood,” promising a grand vision that would constitute “big ball” rather than small ball thinking.

“With several major projects on the way, it’s a rare alignment and gives us a unique opportunity we haven’t seen in decades to design and foster a new neighborhood that demonstrates the downtown is for everyone,” Harrell said. “So when I talk about big ball in our administration, this is it a chance to significantly increase people living downtown with affordable housing and grocery stores and childcare and high quality jobs.”

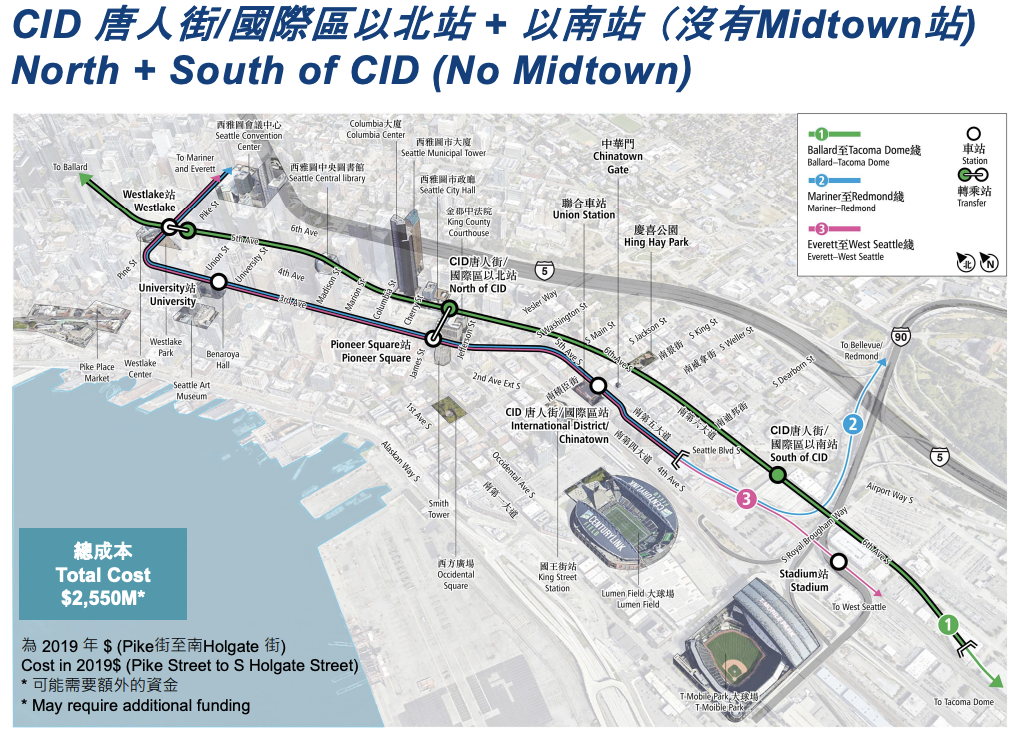

That geography aligns with King County Executive Dow Constantine’s plan to redevelop the County’s campus with a dense mixed-use vision, as well as roping in several substantive projects planned in coordination with other government partners, like the Washington State Department of Transportation. Both Harrell and Constantine led the charge to redesign downtown’s second underground light rail line to skip Chinatown and instead stop in the middle of the county’s campus in Pioneer Square and south of Chinatown on the edge of developer Greg Smith’s massive “S Campus” property. The last-minute changes to the plan has delayed the planning and delivery of the Ballard Link project.

Threading the needle to encourage intense development all around Chinatown while preventing gentrification and preserving the cultural vitality and cohesion of the neighborhood itself, which was the justification for cutting the new light rail station in the heart of the neighborhood, could prove challenging for the mayor.

Comprehensive plan draft release set for early March

The mayor said a long-delayed draft of the One Seattle Comprehensive Plan would finally be released in the next two weeks. Given the delays, Seattle will have a very tight timeline to finalize and approve the plan before the state deadline at year’s end. The delays have been attributed to the new state mandate for allowing missing middle housing and could indicate Harrell will pursue an exception that allows him to keep up to 25% of single-family zoning so long as he demonstrates an anti-displacement strategy for doing so.

“This is our master plan for growth. It’s just one part of a bold One Seattle housing agenda that allows new kinds of housing across the city and brings missing middle housing to every neighborhood and expands density citywide with a focus on areas where there are strong transit access, close to shopping, and other services and other amenities and, indeed, families want,” Harrell said. “My housing agenda will create opportunities for new generational wealth, simplifying nearly 300 separate zoning categories to create complete neighborhoods and reduced permitting timelines and other barriers to development.”

Harrell commended the step state legislators took in requiring most cities phase out single-family zoning, but he contended that Seattle is already leading and will continue to lead on housing abundance.

“The State of Washington took an important step in asking every city to do its part and make it easier to build affordable family friendly housing. But Seattle is already leading the way,” Harrell said. “This housing agenda that I’m describing will not only adopt the spirit of these changes, but continue to point the way forward for our entire region.”

For now, two-thirds of Seattle’s residential land remains off limits to apartments and townhomes and set aside exclusively for single-family homes, the most expensive type of housing. After punting many times on the comprehensive plan, it remains to be seen if the next play the Harrell administration has dialed up is big ball or small ball.

Streetcar ghosted

Despite a brief attempt last year to reenergize the stalled-out Center City Connector streetcar extension project (halted under Mayor Jenny Durkan), the streetcar went unmentioned in the lengthy speech in spite of the choice of venue — the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI) — with South Lake Union trams rolling along just outside on Roy Street. Without the extension into downtown and Pioneer Square along First Avenue, ridership on the 1.3-mile South Lake Union line has been anemic — in contrast with the solid ridership the First Hill Streetcar has seen.

With streetcar enemies and budget hawks circling, a very real possibility exists that the City will end up shuttering the South Lake Union streetcar in the name of budgetary belt-tightening, perhaps surviving only as an exhibit at MOHAI. An increased budget estimate revealed in January has deflated hopes for restarting the Center City Connector project any time soon.

Notions of austerity

Nonetheless, Harrell sought to avoid the frame of austerity, even as he moved to embrace the tools and trappings of austerity.

“Now is not a time for despair. I reject notions of austerity,” Harrell said. “Instead, this is a chance to hit reset, revise our budgeting practices and to double down on the programs, projects, and policies that are effective and making the most difference for the people of Seattle. It will be data driven, guided by the city’s first One Seattle data strategy and an executive order issued last year to optimize use of data to make better, clearer financial decisions based on our values. Our pace of spending requires a systemwide analysis of every expense stream and line of business, as well as a granular analysis of every dollar spent.”

A data strategy bearing the mayor’s trademark “One Seattle” brand and a pledge to pour over every dollar spent in the City’s $1.7 billion general fund in granular detail may sound nice to those hoping for budget discipline. But the hard decisions will remain, perfect data or not. Seattleites received little indication of what those will be.

Office conversion incentive proposal pledged in March

One concrete pledge Harrell did make was to deliver an incentive package for office-to-housing conversion projects, a much-hyped phenomenon in the pandemic era, but one that has not seen much implementation in Seattle. In last year’s state of the city speech, Harrell announced a design contest that has yet to the move the needle on actually delivering office conversions.

“So next month, my office will deliver legislation to the city council to turn this big idea into a reality through permitting improvements and incentives based on insights from architects and building owners and housing leaders and housing advocates,” Harrell said.

Much touted as a concept that could breathe life into some of downtown’s quieter areas, office-to-housing conversions have proven much trickier to implement in practice. Last year, the idea of converting a substantial portion of the iconic Smith Tower to housing was floated but never materialized, according to the Puget Sound Business Journal. “We just haven’t seen the value of office in Seattle drop to the point where people are giving away office buildings at a price that makes sense for conversion,” affordable workforce housing developer Ben Maritz said in an interview. (Full disclosure: Maritz is on the board of The Urbanist.)

Bringing Sonics back

The mayor’s Downtown Activation Plan also includes continued prayers and overtures for a return of the Seattle Supersonics NBA franchise. The Sonics’ former owner, Starbuck CEO Howard Schultz, sold the franchise to Oklahoma City oil barons in 2006, much to fans’ chagrin, but Seattle mayors have continued to lobby for team’s return ever since.

“NBA teams are already choosing to play preseason games right here and that’s a clear sign that Seattle Center and Climate Pledge Arena are ready for NBA action,” Harrell said.

Safety, surveillance, and police recruiting

Another aspect of the mayor’s downtown activation plan is public safety, a steady theme throughout the speech. The mayor celebrated a downward trend in most categories of crime in 2023. However, the 72 homicides tallied last year set a 30-year high.

The mayor touted his Civilian-Assisted Response and Engagement (CARE) program, a pilot funded last year aiming to civilianize some crisis calls with a dual-responder model lesser in scope than what some peer cities have attempted. “What does innovation mean? Innovation means a new Community-Assisted Response and Engagement department, a CARE department, to better help our neighbors in crisis resulting in improved and improved holistic approach to a diversified public safety system,” Harrell said.

Other cities have shown civilian response can work and improve outcomes, lessening strain on struggling police departments. However, Seattle’s pilot program would be small-scale and the Mayor stopped short of pledging to scale it up. Such an innovation will need to wait for beyond the pilot phase.

Harrell gave new policing technology a brief mention, alluding to his plans to roll out a new surveillance regime including gunshot detection devices, closed circuit cameras, and new software to process the new streams of surveillance data.

“Now I will repeat: there are too many guns in this country on our streets and in the wrong hands. We know this,” Harrell said. “We need to embrace new technologies funded in this year’s budget to enhance the fair, effective, and constitutional policing of our officers.”

Harrell did not bring up his 1,400-officer goal for Seattle Police Department staffing — perhaps an indication of how far off that goal remains given the national police officer shortage — but he did highlight some lesser recruiting victories.

“We are urgently recruiting more police officers who share our values,” Harrell said. “Our monthly applications are the highest they’ve ever been in three years. We have comprehensively reviewed our recruiting system, and we’re continuing to make changes to processes that have not been changed or touched in decades. I don’t know if moving from paper to online applications counts as innovation or just plain common sense. But either way, it’s an example the kinds of steps needed to record a new generation of officers who continue to serve our neighborhoods and represent our communities, our communities and keep us safe.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.