Within 18 months, the posted maximum speed limit on nearly every single arterial street in the city of Seattle will be 25 miles per hour. That was the boldest action on the list of safety improvements announced by Mayor Jenny Durkan yesterday, in response to a big uptick in traffic violence.

More than two years into her mayoral term, Durkan had been criticized for being slow to act on the issue, and had not acknowledged recent tragic events like a recent deadly collision on Aurora Avenue involving four pedestrians before the press conference. Nonetheless, the latest tragedy did spur the Mayor to action.

The move to lower speed limits across the board comes in stark contrast with the previous glacially slow pace of rollout–most often in conjunction with design changes. The last big rollout of lower speed limits was in 2016 when Mayor Murray announced 25mph limits on Downtown streets and 20mph on neighborhood (non-arterial) streets; he hinted that arterials would be next, but that didn’t happen until now–after three years of rising pedestrian deaths and injuries.

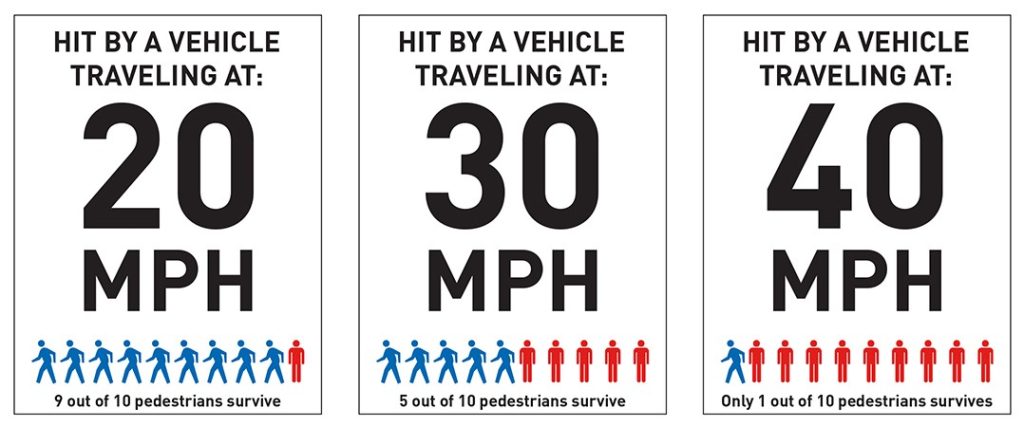

Lower speed limits have been effective where they are in force. “On roads where the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has already implemented a 25 mph speed limit, the department has measured a 35% reduction in crashes, a 20% reduction in severe injuries and deaths, and negligible impacts to traffic congestion,” the Mayor’s office said. Research has shown that lower speeds greatly increased the chance that a pedestrian survives a collision wherein a motorist runs them over.

The move will get Seattle drivers, accustomed to being able to go 30 mph (or more) on their neighborhood connectors, used to lower speed limits, but design changes on high-crash corridors will also be essential. Thankfully, Seattle’s nine-year transportation levy already has a dedicated budget for redesigns like this.

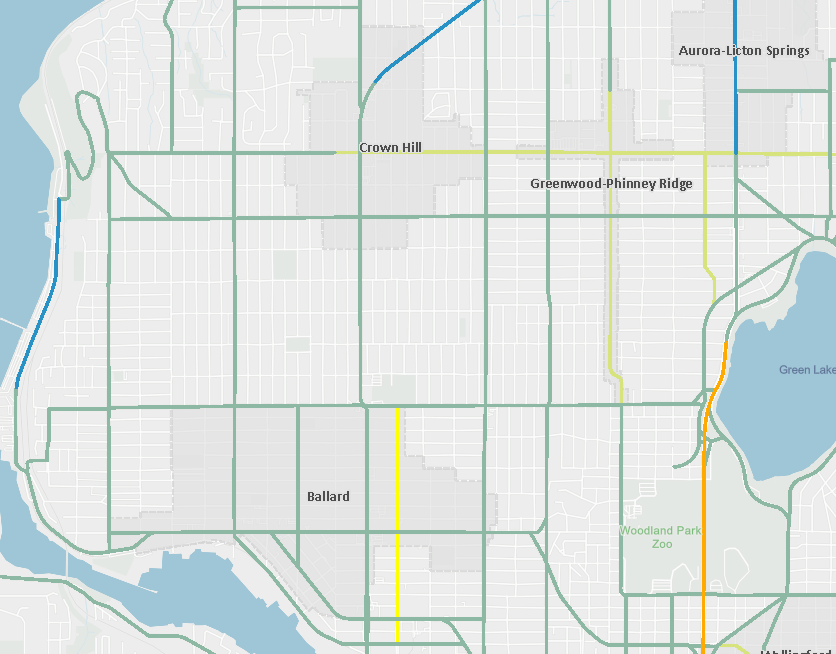

At the press conference, attendees walked outside and watched Mayor Durkan unveil a new 25 mph sign on Rainier Avenue, which filled in the gap between two existing 25 mph zones in Columbia City and Rainier Beach. The change will be a big drop, particularly on a few streets that currently act as speedways, like Sand Point Way NE and Martin Luther King Jr Way S. City streets that are also state highways like Aurora Avenue and Lake City Way will require coordination with the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), but Mayor Durkan promised that those streets would also be moving toward lower limits. A state official voiced support in the Mayor’s press release.

“WSDOT’s goal is zero deaths or serious injuries on our roads and highways by 2030 because one is just too many,” WSDOT Regional Administrator Mike Cotten said. “With that goal in mind, we are committed to working closely with the City of Seattle, transportation service providers, and the traveling public to make this a reality.”

Doubling the Number of Leading Pedestrian Intervals

The City’s primary pedestrian safety initiative, installing Leading Pedestrian Intervals (LPIs), which provide the walk signal an extra few seconds before a green light to give pedestrians a head start on drivers trying to occupy their space and possibly maim or slaughter them, will also see a continued ramp-up next year. There are currently close to 125 intersections with LPIs installed, and that will be doubled to 250 under the Seattle Department of Transportation’s new goal.

Leading Pedestrian Intervals pair well with right-turn-on-red restrictions, preventing drivers from cutting off pedestrians even during the leading interval. SDOT had originally led with right-on-red restrictions in 2015 after its Vision Zero announcement, but there is no goal for increasing instances and the Vision Zero team has declined to recommend a blanket policy of eliminating right turns on red. Which is not to say that SDOT has stopped restricting turns at select intersections, but a more comprehensive approach will be required. San Francisco is considering a city-wide ban and Seattle should as well.

More Speed Cameras

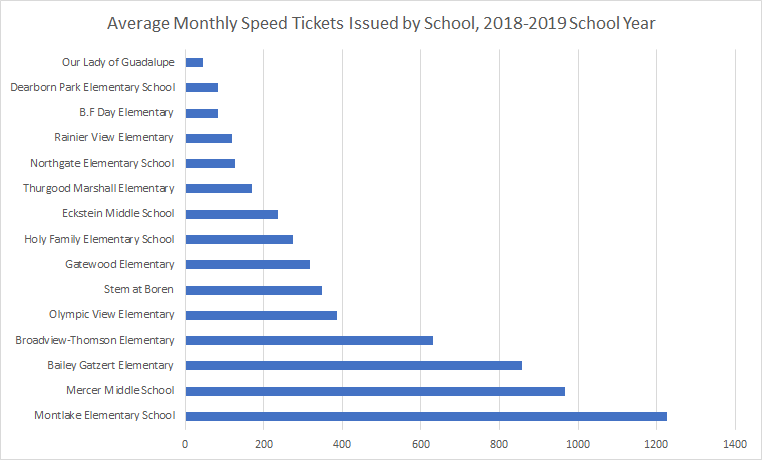

Mayor Durkan also announced that SDOT will be installing more cameras that issue tickets for running red lights, as well as cameras that issue tickets for speeding outside schools immediately around school hours. There are currently speed cameras at around 15 schools in Seattle, with the design of the streets having a big impact on how many tickets are issued. The school with the most tickets, Montlake Elementary, sees around 10 times as many as the camera at Our Lady of Guadalupe School in West Seattle does, for example. A 2018 “Vision Zero” project at 24th Ave E in Montlake went out of its way to not slow down very many cars, emphasizing how important it is for school zone cameras to be paired with robust design changes.

Major Crash Review Taskforce

Also part of this Vision Zero resurgence is the creation of a Major Crash Review Taskforce. If properly directed, this could galvanize data around collisions on Seattle’s streets to provide comprehensive recommendations for high-crash corridors, much like the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s High Crash Network. An oversized proportion of the serious injuries on our streets happen on the same corridors and it often takes too many tragedies to recognize a trend more broadly. Seattle could also adopt Portland’s policy of placing traffic information signs at the site of a deadly crash to highlight the frequency of traffic violence for those who are able to hide comfortably behind a windshield.

Finally, SDOT has announced it will be conducting education campaigns via Vision Zero “street teams” to talk to drivers as well as people biking, walking, and rolling about safe practices on our streets. Depending on how these are conducted, they could be an effective community engagement tool or a waste of time. However, they will also be partnering with the Seattle Police Department to conduct pedestrian safety trainings with drivers at unsignalized crosswalks, handing out warnings for drivers who fail to yield, a perpetual problem.

The actions announced Tuesday were a very positive step by a city government that has mostly taken its pledge to dramatically make its streets safer for granted. They were also a good sign for SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe, who is still in his first year and just hitting his stride. Taking the lead and showing other cities how to lower speed limits is a bold and welcome move, but the slate of policies will require follow-through and more pushing from safe streets advocates to translate to lasting change.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.