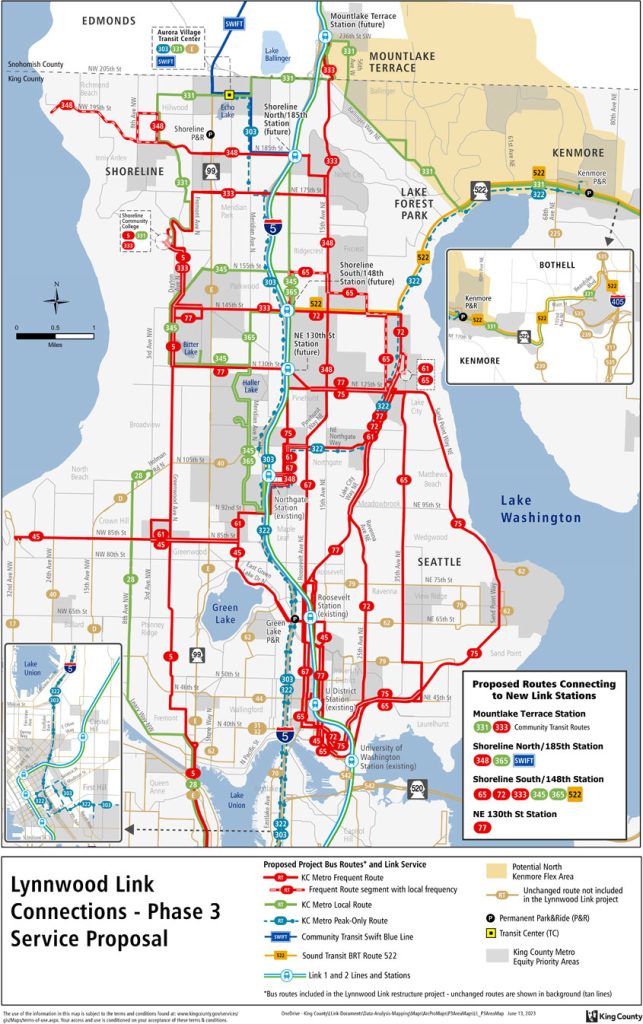

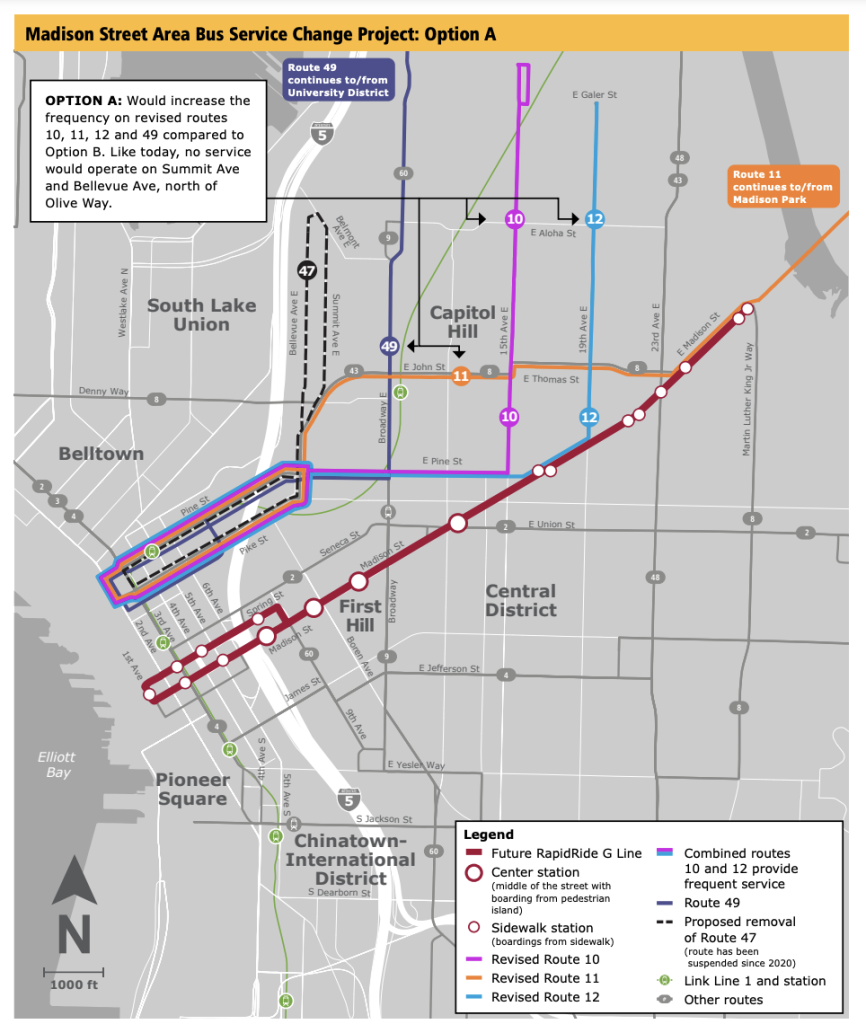

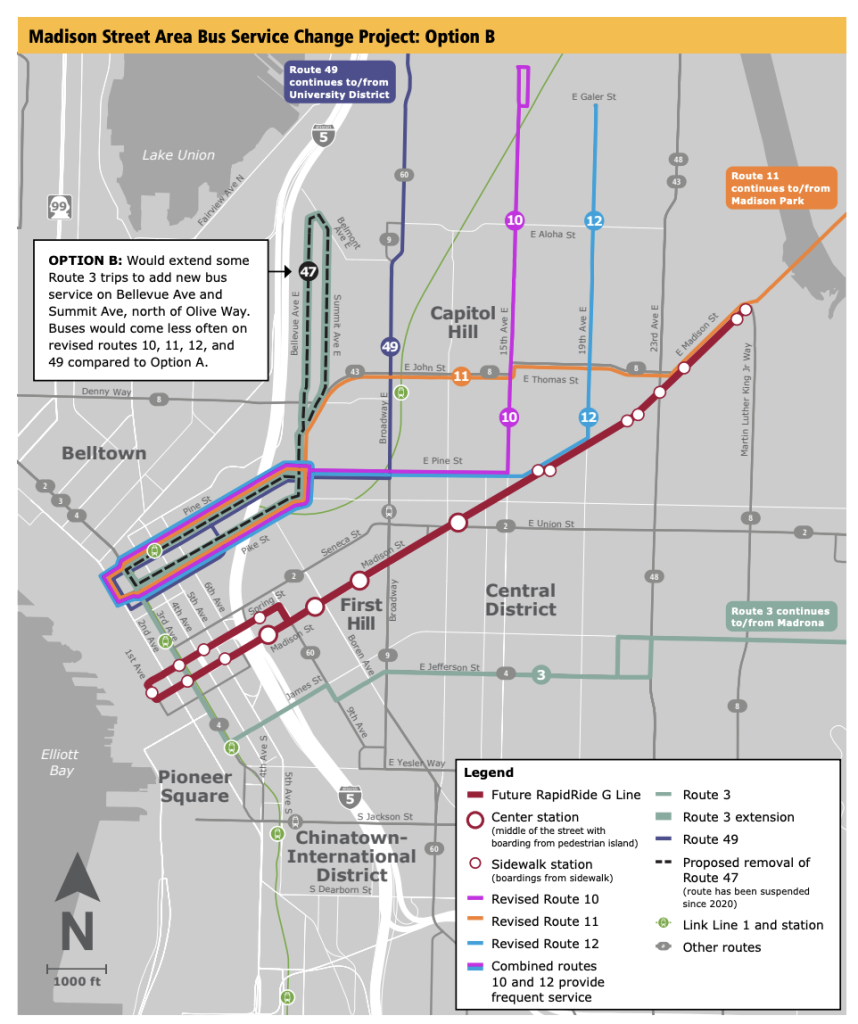

King County Metro recently unveiled its final proposal for a bus restructure in parts of North Seattle and North King County as well as a second round bus restructure proposal for Capitol Hill and First Hill. Those efforts are meant to complement the Lynnwood Link Extension and RapidRide G Line opening in 2024. The problem with them, however, is that the restructures are sacrificing local bus service to support new high capacity transit services instead of building upon the local bus network to support them.

That’s not exactly a new trend for Metro, but it is one that has gotten markedly worse over the years. And in the process, this has been dealing damage to the agency’s brand and trust among riders all in service of adherence to outmoded service guidelines when it comes to this type of restructure.

Metro has a flawed approach to bus restructures spurred by new rapid transit

To be sure, bus restructures underway might be less painful if Metro had already fully recovered from the pandemic and were in a growth swing. But Metro has been dealt a decidedly bad hand — part of it self-inflicted. The pandemic challenged the agency with fears of fiscal cliffs, plummeting ridership, transit operators and maintainers leaving in droves, and service levels being curtailed. As the agency moved out of the depths of the pandemic, hiring and retaining staff has not gone well, out-of-service equipment levels have spiked, and as a consequence of both the agency has had to keep cutting service hours.

By virtue of having fewer service hours to work with, Metro’s restructures need to be able to provide realistic service on day one while achieving overarching objectives to connect with new rapid transit lines, and in the case of the RapidRide G Line, reallocating existing service hours to operate the line itself. And herein lies the fundamental problem with Metro’s bus restructure service guidelines. They make no promise to grow the pie. Instead, outside the context of a big systemwide growth swing, they encourage eating away at the pie even if ridership within a restructure study area is solid. The consequence is that Metro delivers a smaller, less frequent local bus network than riders had before.

For many riders in the Lynnwood Link and RapidRide G Line study areas, they’re losing access to their nearest all-day bus routes and getting lower frequencies and span of service. That’s not just a problem to attract and retain riders in the bus system, it’s also a political problem. Voters have been approving transit measures in recent years because they have been promised increased service levels on local bus routes and build out of new rapid transit lines, but the promise of both is not being delivered equally and it is engendering serious distrust of Metro staff, politicians, and transit funding measures. The current approach is unsustainable, especially in the context of a rapidly shrinking and unreliable bus system — with more service cuts coming in September.

Metro might deserve less flack for what’s happening now if the service guidelines had gotten a proper overhaul in 2021 and the agency hadn’t reneged on the previous North Seattle bus restructure. But alas, the service guidelines update was superficial and Metro chose to run away from a growth restructure for Northgate Link when the agency believed it faced a fiscal cliff in 2020. That came on the heels, too, of a messy North Seattle restructure for U Link that also hobbled local bus service in Capitol Hill and Montlake.

Indeed, connecting local buses with high frequency, fast service is a worthy and good objective. But, coupling local bus service with too few resources starves the wider network, leaving riders to suffer the consequence of longer walks to bus service and less frequent service to nearby destinations. Shrinking local bus service thereby pushes many people to choose driving over transit and encourages counterproductive urban land uses, reinforcing a localized vicious cycle for transit.

Metro’s bus restructures are leaving communities behind

In 2021, suburban elected officials partially recognized the risks to local bus service following an event where Metro declared service duplicative in the Northgate Link bus restructure and ferreted service hours entirely out of a service area. That happened with tens of thousands of annual service hours when Route 41 was deleted in North Seattle. As a result, suburban elected officials decided to try and constrain that in future restructures with revisions to Metro’s service guidelines. As the East Link restructures have advanced, there has been pressure not to make service duplicative, but the reality of falling service capacity has constrained the restructure process and meant that there will be many net service losses to Eastside communities.

But there are other future restructure victims out there. When Metro comes to Kent, Des Moines, and Federal Way for the Federal Way Link restructures, local communities are all but sure to be left facing cuts. And when Sound Transit’s Stride bus rapid transit lines arrive later this decade, more South King County and Eastside communities are likely to be left out to dry.

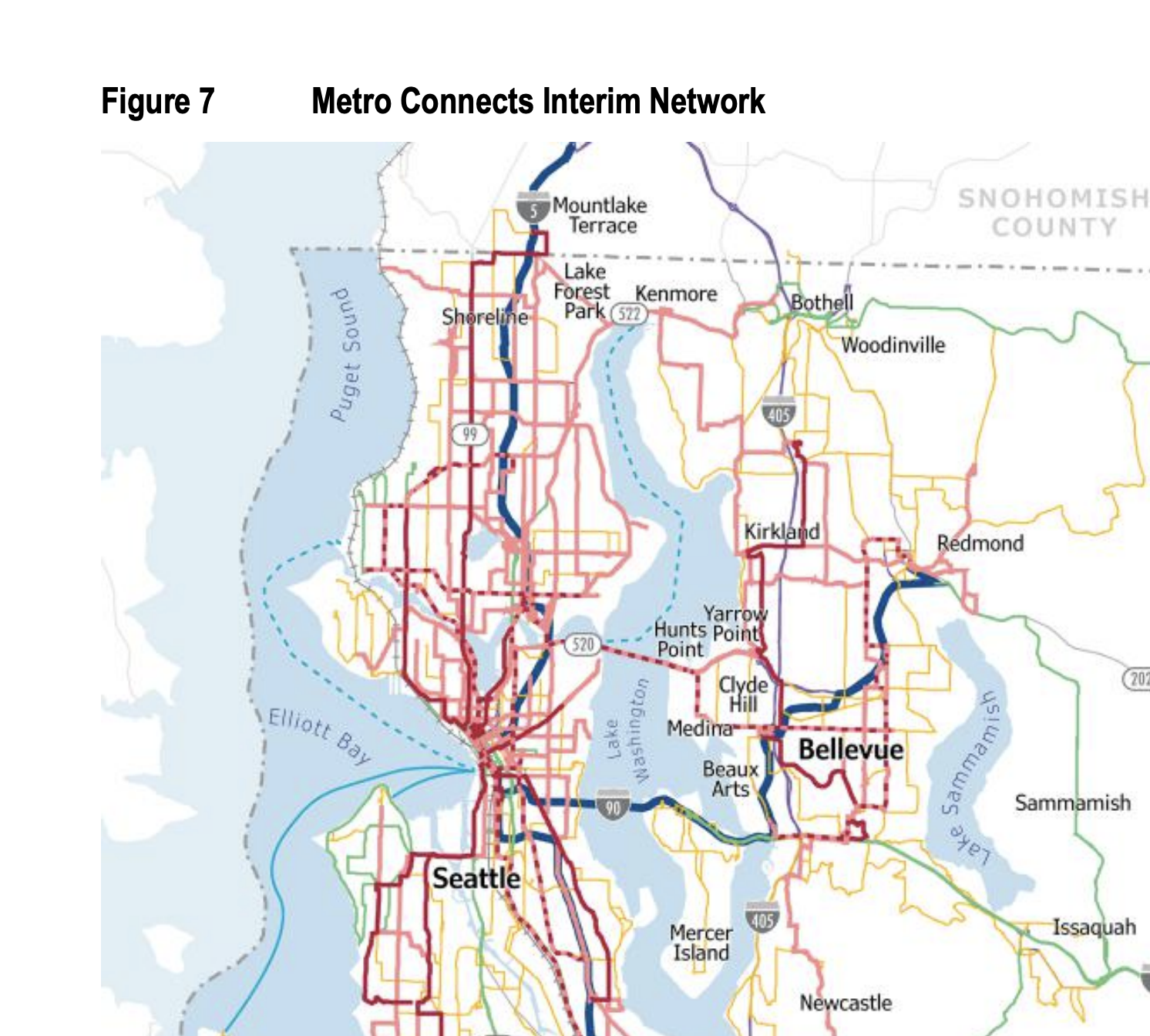

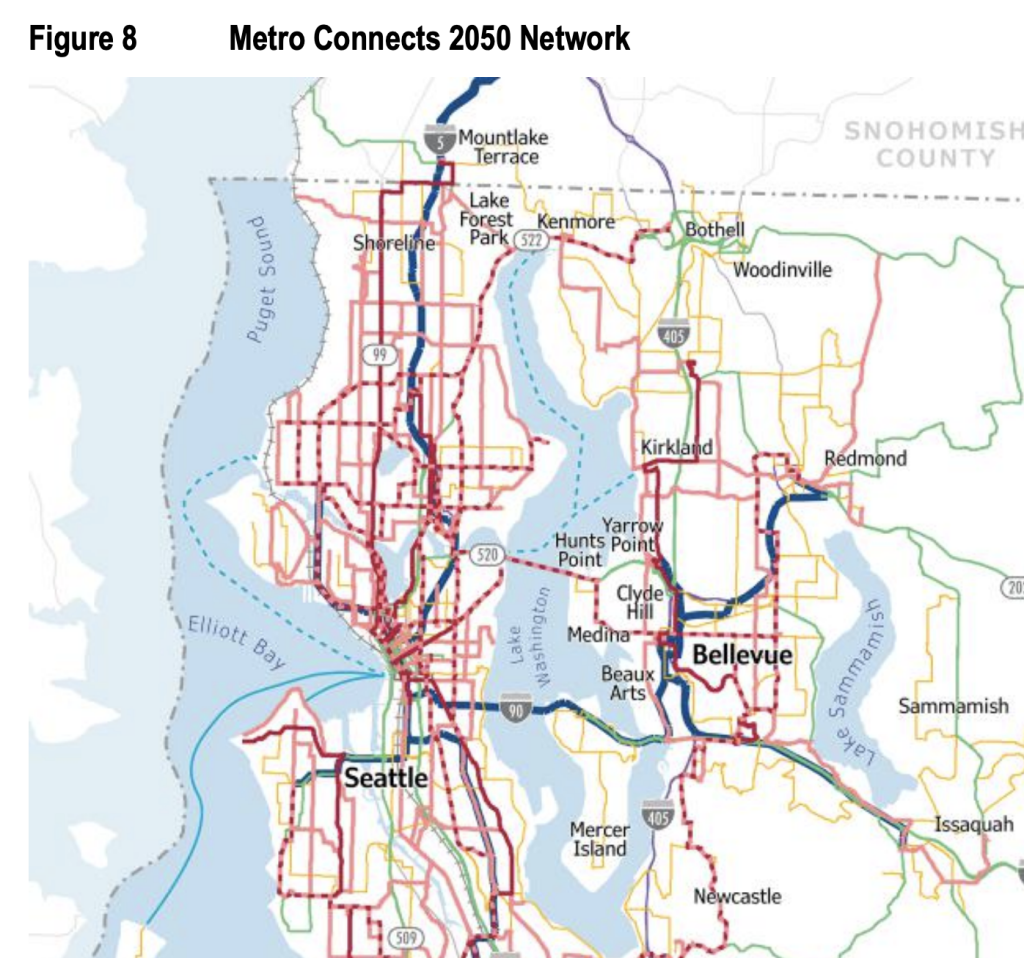

All of these restructures hold a common thread that the most frequent transit service type being delivered is very good, but nearly everything else is worse off all things being equal. Metro needs to fix this paradigm and that starts by completely reforming the restructure process that promises a better future — as promised by the long-term Metro Connects plan — not a lesser future.

Metro needs new restructure plans and targeted changes to service guidelines

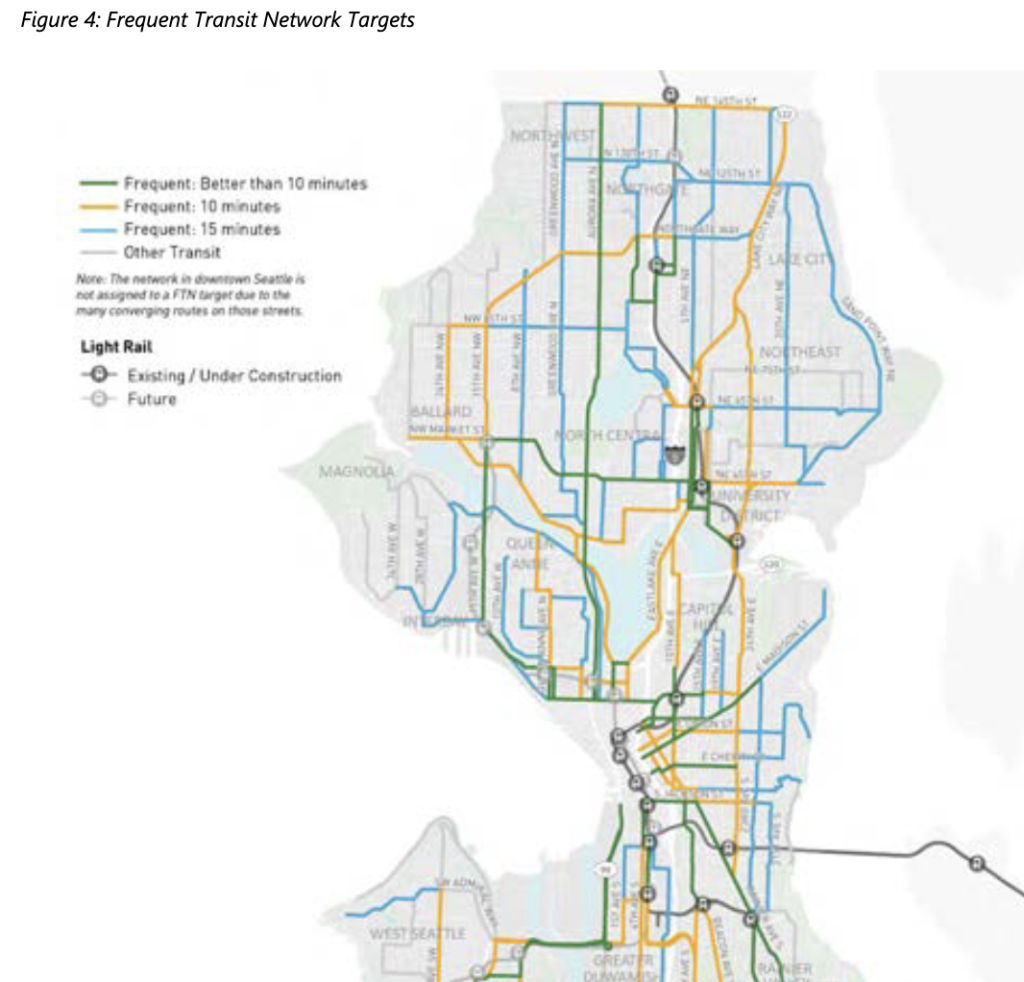

Metro needs to go into bus restructures by looking at pre-pandemic service levels and planning from that baseline. As part of this, Metro needs to identify additional service hours to reasonably maintain the framework of the existing network. That doesn’t mean the network cannot change, but that neighborhoods and corridors are not fundamentally losing local service and service levels in the process, especially ones identified in Metro Connects and local comprehensive plans. In other words, Metro needs to deliver on the promise that the agency will “get you there.”

Invariably, it may be a reality that Metro cannot deliver a better future in the course of an immediate restructure. That’s especially the case when the agency is, on net, losing maintenance and operations staff like it is now. A backup plan — perhaps like the Lynnwood Link bus restructure being proposed — could be appropriate to accompany a proposal that commits to more resources. But such a backup plan cannot be the permanent baseline and goal of Metro.

To remedy the austerity restructure problem that Metro has, the King County Council should take immediate emergency action to revise Metro’s service guidelines and issue a directive back to Metro to amend all of its pending bus restructure proposals before sending final proposals to the King County Council for consideration and approval.

There are two principal sections of the service guidelines that the King County Council should focus on amending: “Restructuring Service” and “Route Spacing and Duplication”. The restructure service section gives Metro very little guidance and expectations in restructures writ large. But that should at least change for restructures initiated because of “Major Transportation Network Changes” (i.e., new rapid transit investments).

Metro should be compelled to deliver restructure proposals related to transportation network changes that:

- Assume the peak level of annual service hours in the geographic area since the last restructure affecting the area;

- Reasonably maintain the framework of the existing network for local bus service; and

- Identify additional resources needed to achieve objectives of integrating local bus service with new rapid transit service.

Where Metro is unable to reasonably deliver on such a proposal with expected and requested resources, the agency should be permitted to develop a parallel interim proposal that reasonably can be delivered. Both proposals should be put forth and become binding, with the larger proposal going in effect as soon as resources allow.

Additionally, Metro should be explicitly prohibited from considering redeployment of duplicative service outside a restructure study area and route spacing criteria should be altered in areas that have a density of 7,500 residents or greater per square mile, according to census tract data. Within areas that achieve that level of density, route-spacing criteria should be adjusted such that no route is closer (generally) than a quarter-mile instead of a half-mile.

While the half-mile criteria may be appropriate for many suburban contexts where ridership is much lower and threading routes is more complicated, higher density urban areas that aren’t near a transit or in a regional growth center shouldn’t be punished under agency policy. Metro, in fact, should have an explicit goal of building up a much denser network of all-day and frequent service routes in urban areas where transit is an attractive mode and can be supported by complementary land use and ridership levels.

Ultimately, politicians, and riders, have several jobs in light of the pending restructures. Politicians should immediately pause advancement of the restructures, revise Metro’s service guidelines, and issue new directives to Metro staff to create phased restructure plans to deliver on promises made to riders and voters, while riders should demand that politicians and staff take these actions with all due haste. These restructures are a warning that Metro will continue to undermine local bus networks and access to transit if agency policies don’t change right now. Riders need to treat this emergency like the one it is by ringing the alarm bells loudly.

Riders and transit advocates should provide feedback to Metro through its Lynnwood Link restructure survey (open through August 27) and RapidRide G Line restructure survey (open through August 31). Riders and transit advocates would also be wise to contact the King County Executive, King County County Council, Regional Transit Committee, and Metro via email about their concerns with Metro’s restructure processes and pending restructures.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.